The United Community Corporation

(War on Poverty)

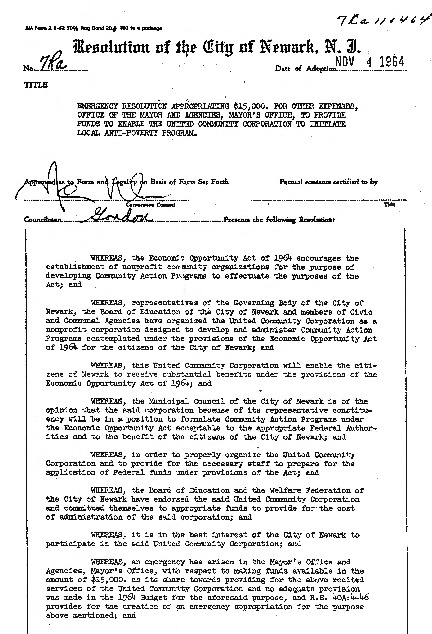

In 1964, the War on Poverty was created because of the momentum generated by the Civil Rights Movement. President Johnson said it would cure the nation’s “problem” of poor people through a variety of social programs. The violent rebellions in Birmingham and Harlem in 1963 and 1964, respectively, put “poverty” on the government’s fast track. The Federal Government looked to head off future unrest with grants for programs coming through the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO). The OEO provided funding for Community Action Agencies to coordinate anti-poverty programs. Newark’s Community Action Agency was established in 1965 and called the United Community Corporation (UCC).

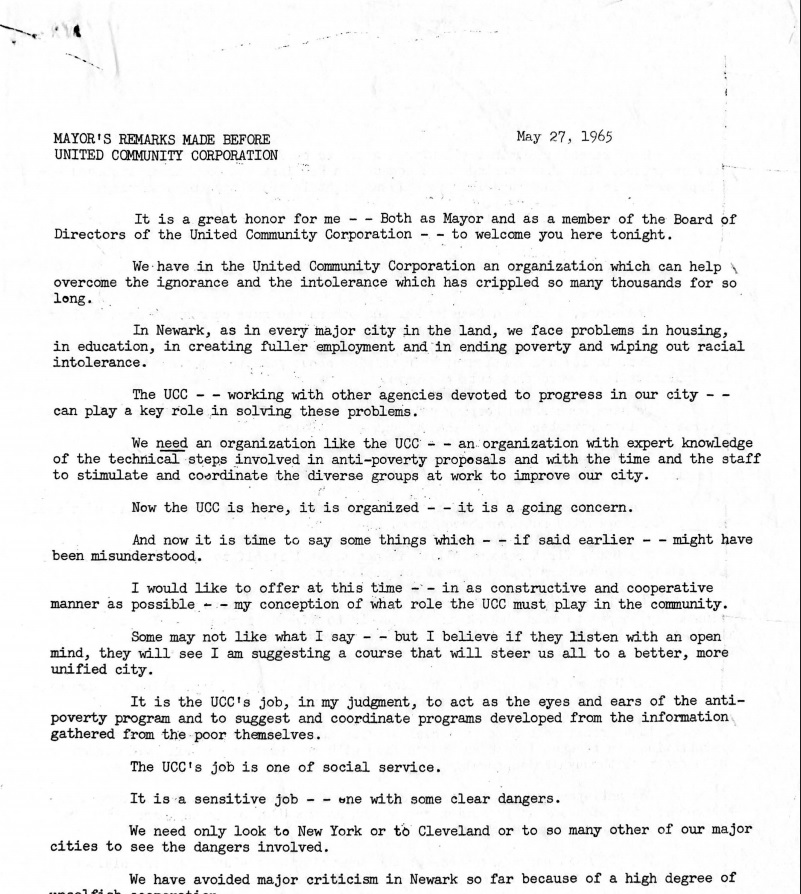

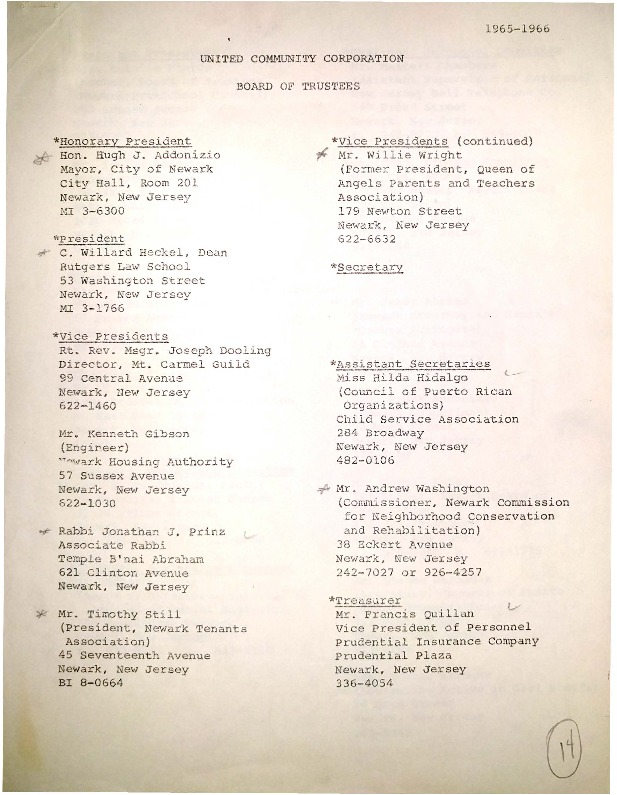

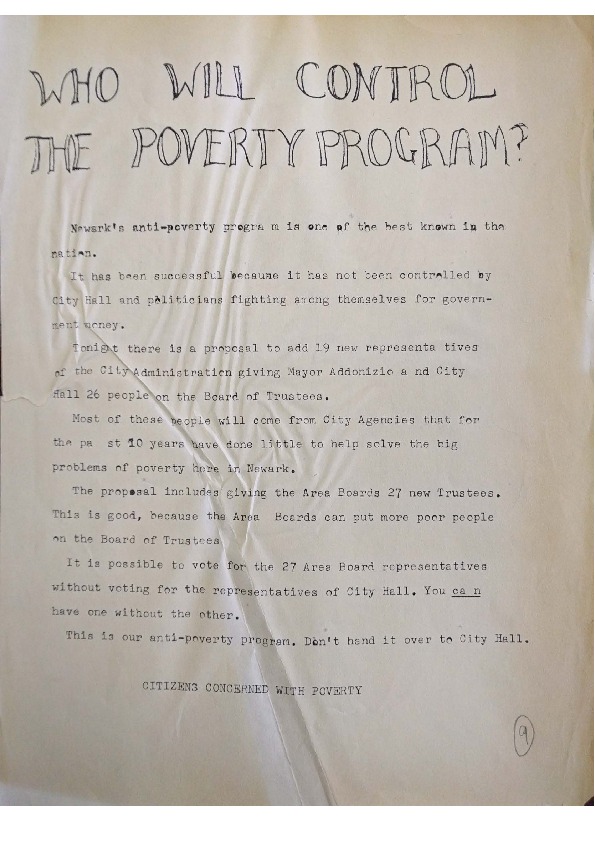

The OEO legislation included a phrase that sent shock waves throughout city halls around the nation with its declaration that anti-poverty programs that it funded had to assure “maximum feasible participation of the poor.” This led to a new phase of struggle in Newark where community groups such as the Newark Community Union (NCUP), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the United Afro American Association (UAAA), and allies from the Black Political Class who were then in disfavor and at odds with Mayor Hugh Addonizio, formed an unpredictable and highly unstable coalition to fight the Mayor for control of the program, which at the bottom line meant jobs for each combatant’s constituency.

This produced a brand new organizing chapter beginning in late 1964. “Development” of the community participants meant learning another set of “insider” skills.

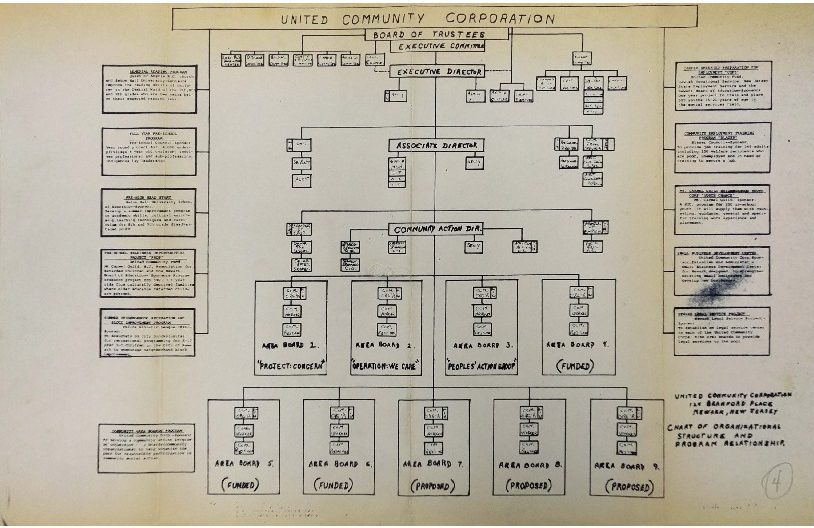

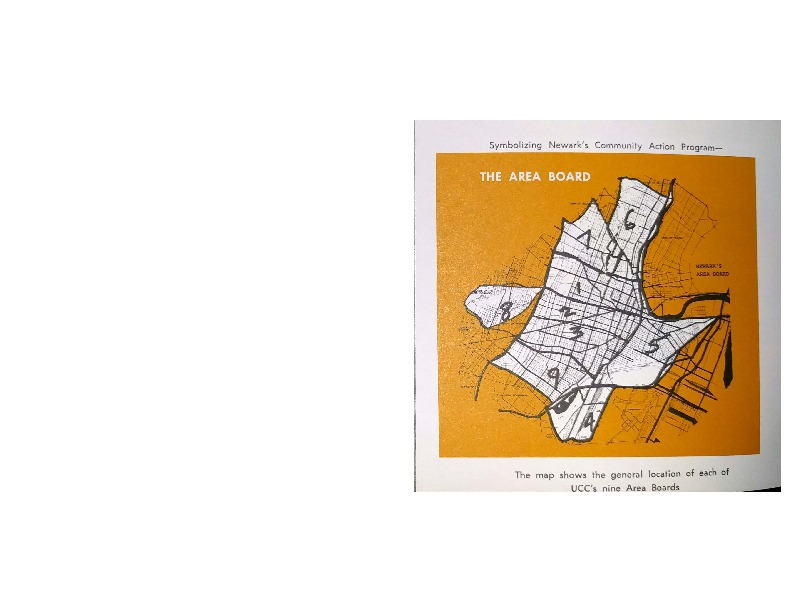

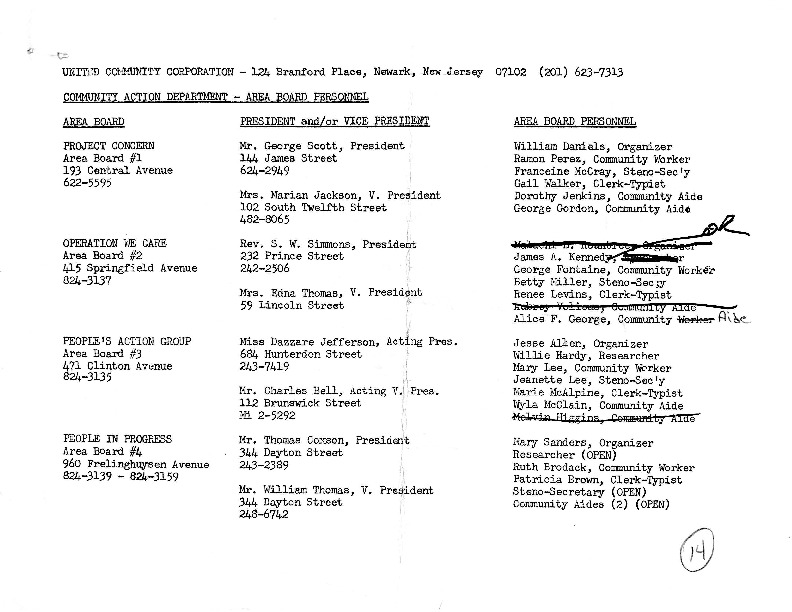

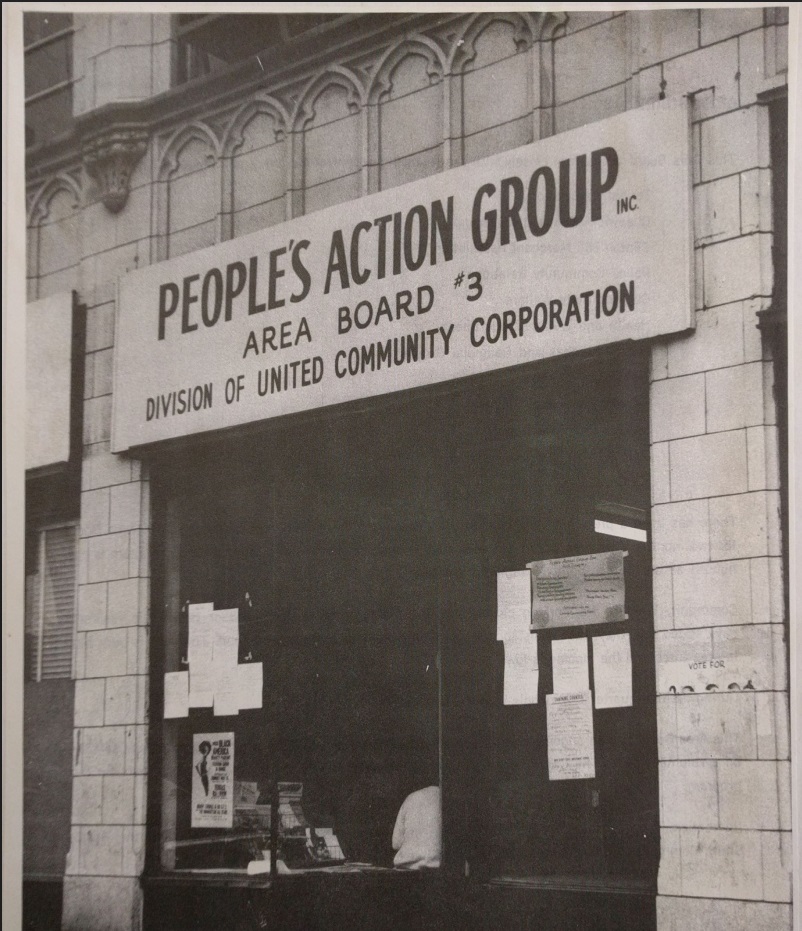

Newark’s anti-poverty plan adopted the model of decentralized Area Boards urged by Cyril Tyson, from New York’s HARYOU-ACT youth employment program. Under the vision of Tyson, who became the first Executive Director of the UCC, there would be nine Area Boards, each with a separate Board of Directors and a budget for staff and programs. NCUP took over Area Board III as its home base in the South Ward, while the UAAA (Willie Wright) took over Area Board II in the Central Ward.

Tom Hayden, of NCUP, said that he saw the UCC as “a government for the liberals!” He meant that it became the institutional staging ground for a war not so much against poverty, but by insurgents, and exiles from the Mayor’s, working against the city Democratic Party political machine, all for the control of money.

Television commercial from President Johnson’s 1964 campaign that highlights LBJ’s War on Poverty programs. One of the most impactful of the War on Poverty programs was the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which authorized the establishment of Community Action Agencies, like the United Community Corporation in Newark.

Clip from an interview with Cyril Tyson, founding executive director of the United Community Corporation (UCC), in which he explains the organization of “area boards” within the UCC. Tyson explains that these local area boards were established as Community Action Programs to promote community participation in the antipoverty program throughout the city of Newark. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

The UCC Battles as a Training Ground

To some, UCC meetings were a training ground. People were jumping up all over the place, objecting to what was said, using Robert’s Rules of Order to hammer their opposition into submission. The air reeked of testosterone. Most of the verbal combat was among black men, but a few women were involved as well. The objective in these shouting matches was very seldom enlightenment, but always about power. UCC meetings were showdowns amongst at many as 100 to 200 people at the Central Board meetings, and were not for the faint of heart. Junius Williams remembers seeing “more black folks fighting black folks than I had ever witnessed before… portents of things to come.” When black people fight white people, as under the rule of Jim Crow, the battle lines are clear. But when black people fight each other, the issues become more muddled: ordinary people got confused and backed away because the fight was around unexplained but dominant class issues, or personalities.

Community groups learned about building coalitions, joining other insurgents, which included members of the Black Political Class out of favor with Mayor Addonizio. This meant they had helped elect the Mayor, but he failed to deliver as promised, so they were at that point against him. Sides could change from motion to motion in a matter of minutes in the meetings, in a shifting game of interests. Early in the game, NCUP teamed up with other South Ward groups and elected charismatic and personable NCUP member Bessie Smith as Chairwoman of the Board in Area Board III. Tom Hayden at the next meeting offered a motion that said 51% of the Board had to be certifiably poor, and “poor” was defined as people who made $4000.00 per year or less.

Clip from an interview with United Community Corporation (UCC) member and eventual mayor, Sharpe James, in which he explains how leadership experience in the UCC impacted the development of political leadership in Newark’s Black and Puerto Rican communities. The UCC was seen by many as a “training ground” for Black and Puerto Rican political participation and political empowerment in Newark. James describes how UCC members such as Earl Harris, Donald Tucker, and Jesse Allen went on to hold elected positions in the city government. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Personal Testimony about the UCC

“I came to love this new arena. UCC meetings, and all meetings where mostly black people are the players, are like jazz improvisation. There is a theme, but once stated, all else gets made up along the way. And everybody got a chance to play. All you had to do was raise your hand, or not raise your hand, and start talking. The speeches and the tactical moves were the solo performances of the evening. And though one might predict an ending, when and how we got to the “bridge” was anybody’s guess! Some of the most brilliant oratory and stage performances I have ever seen were played out on the floor during those hot summer meetings at the UCC. And you had to be tough on your feet to withstand the verbal barrage that would come out of the blue, starting with the proverbial, ‘Point of Order, Mr. Chairman!!” –Junius Williams, NCUP organizer

References:

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power.

Clip from an interview with Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) member Junius Williams, in which he describes the United Community Corporation as a “training ground” for political involvement. Williams explains that the UCC acted as a “government for those of us in opposition” to the established political system in Newark and influenced a new generation of political leadership in the city. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

War on poverty/UCC resources

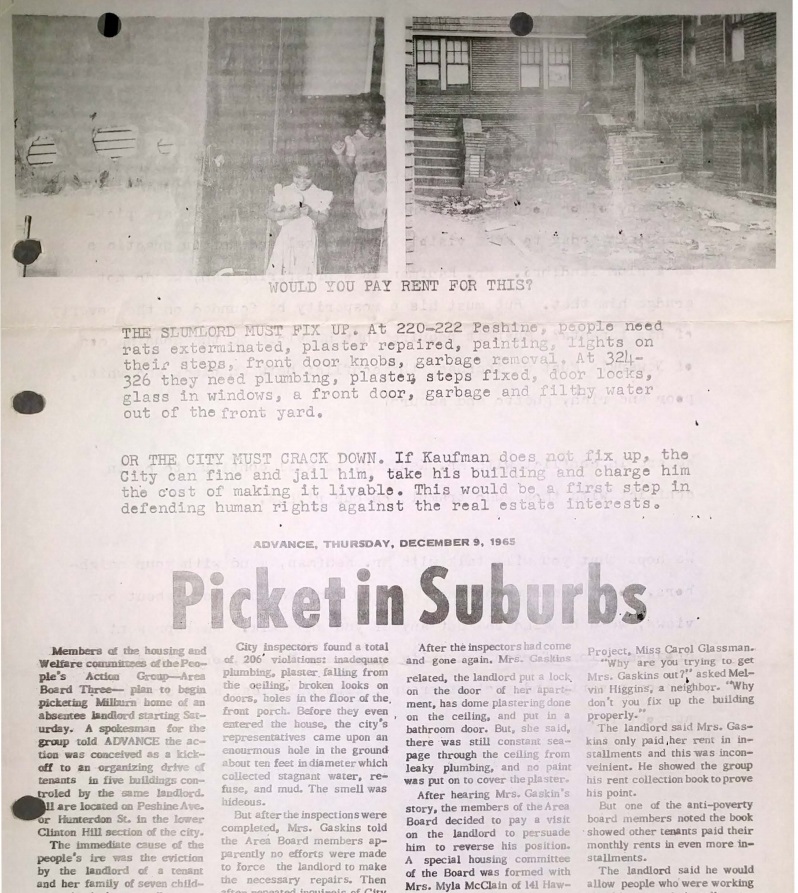

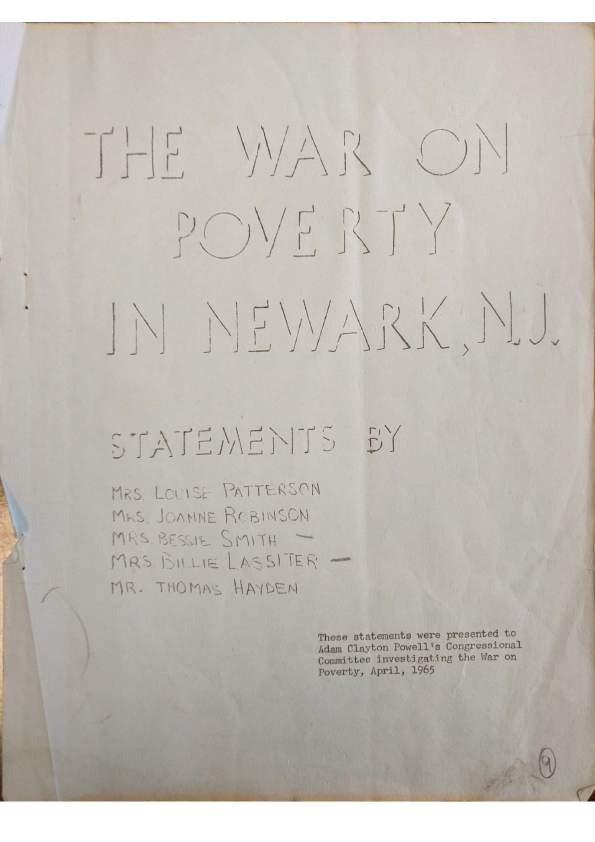

A printed collection of statements presented by members of the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) to Adam Clayton Powell’s Congressional Committee investigating the War on Poverty in April, 1965. In their statements, these Newark residents describe a lack of community representation and involvement in the United Community Corporation (UCC) in Newark. As federal funding arrived in Newark, city officials and politicians jockeyed for control of the money for their own purposes, while the city’s poor communities sought access to the antipoverty programs. Mrs. Louise Patterson explains that “the Area Boards are being taken over by Ward Leaders and speeches by politicians and candidates for political office.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

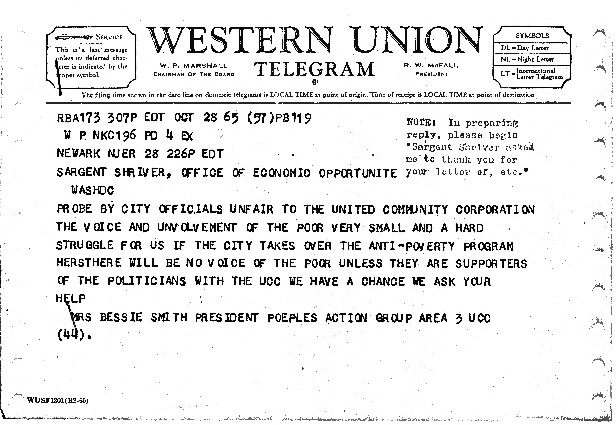

Telegram from Bessie Smith, President of the People’s Action Group (Area Board #3) of the United Community Corporation (UCC), to Sargent Shriver, Director of the Office of Economic Opportunity on October 28, 1965. Mrs. Smith sent the telegram to request Shriver’s assistance in response to the City Council Committee’s investigation of the UCC. Mrs. Smith and many others felt that the investigation was an attempt to bring the antipoverty agency under the control of the Mayor and the City Council. — Credit: Junius Williams Papers

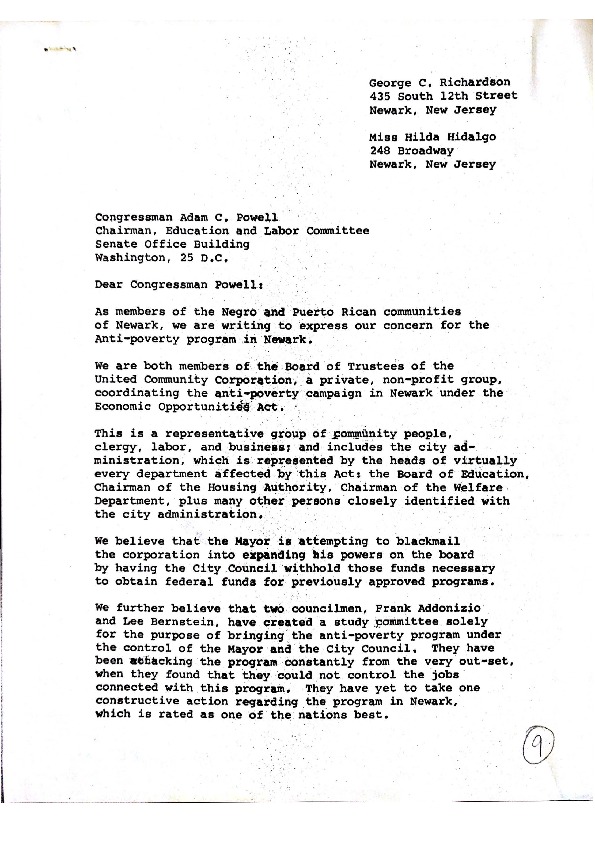

Letter from United Community Corporation (UCC) members George Richardson and Hilda Hidalgo, to Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., seeking assistance in response to the City Council Committee’s investigation of the UCC in 1965. Many Black and Puerto Rican ommunity members, like Richardson and Hidalgo, argued that the Committee’s investigation was an attempt to “bring the anti-poverty program under the control of the Mayor and the City Council.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

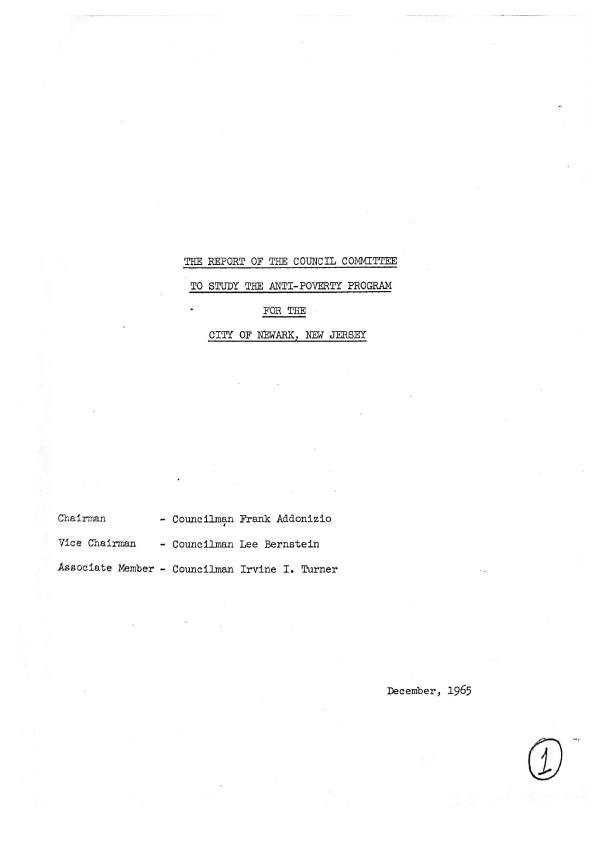

Report of the City Council Committee’s investigation of the United Community Corporation in 1965. The Committee charged that the UCC misappropriated funds and utilized federal money to fund and organize political campaigns. The Committee concluded that the City of Newark “should immediately undertake its own Anti-Poverty Programs and…that it should not combine with or participate in or contribute to any provate groups or non-profit agencies.” Community members like George Richardson and Hilda Hidalgo, however, argued that the Committee’s investigation was an attempt to “bring the anti-poverty program under the control of the Mayor and the City Council.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

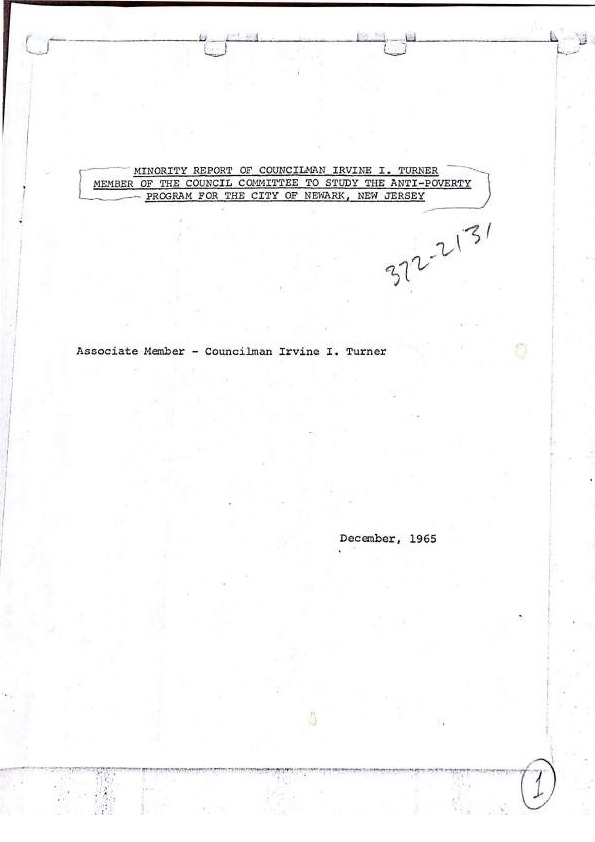

Minority report of Councilman Irvine Turner on the City Council Committee’s investigation of the United Community Corporation (UCC) in 1965. Turner disassociated himself from the Committee’s report on the ground that he disagreed with many of the assumptions and recommendations of the report. In his report, Turner refutes the claim that ‘the UCC has taken many of the aspects of a political-action pressure group,” citing the policy of the Board of Trustees that required any member of the UCC running for political office to take a leave of absence during the candidacy. — Credit: Newark Public Library

The offices of Operation We Care (UCC Area Board #2) and the Small Business Administration program on Springfield Avenue in the Central Ward. — Credit: Newark Public Library

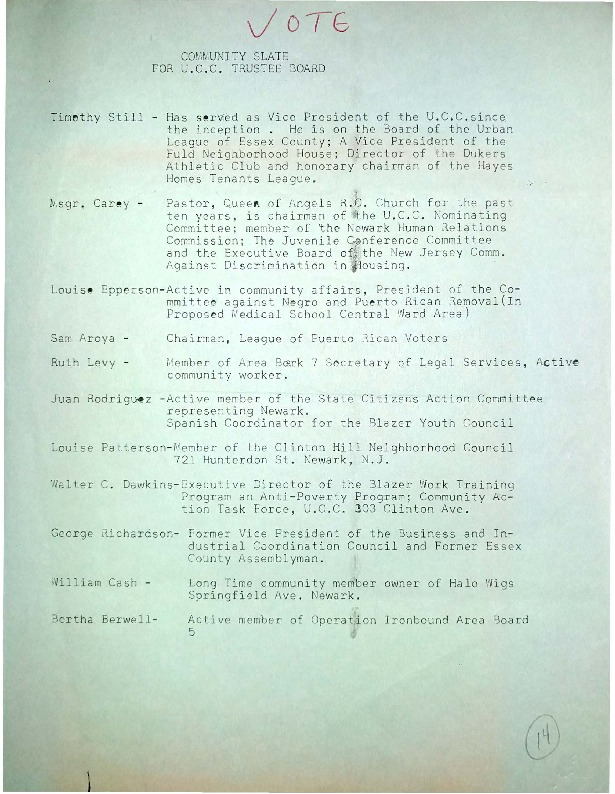

Flyer for the “Community Slate” for the United Community Corporation (UCC) Board of Trustees election. The flyer provides a brief biography of each of the candidates, along with instructions for voting for the slate. In addition to gaining community representation in the UCC, the act of voting for leadership positions in the antipoverty agency was an important aspect of preparing Newark’s Black and Puerto Rican communities for participation in electoral politics in the city. — Credit: Newark Public Library

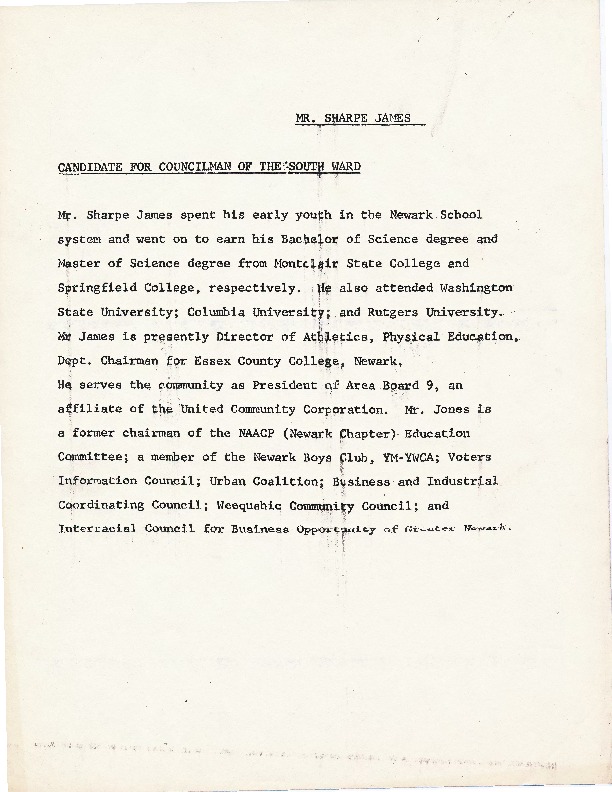

Leaflet from the Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention (1969) promoting the candidacy of Sharpe James for Councilman of the South Ward. Leadership experience gained through the UCC had significant impacts on the development of political leadership in Newark’s Black and Puerto Rican communities. Many UCC members, including Sharpe James, Jesse Allen, Donald Tucker, and Earl Harris went on to be elected to political office in Newark. — Credit: Junius Williams Papers

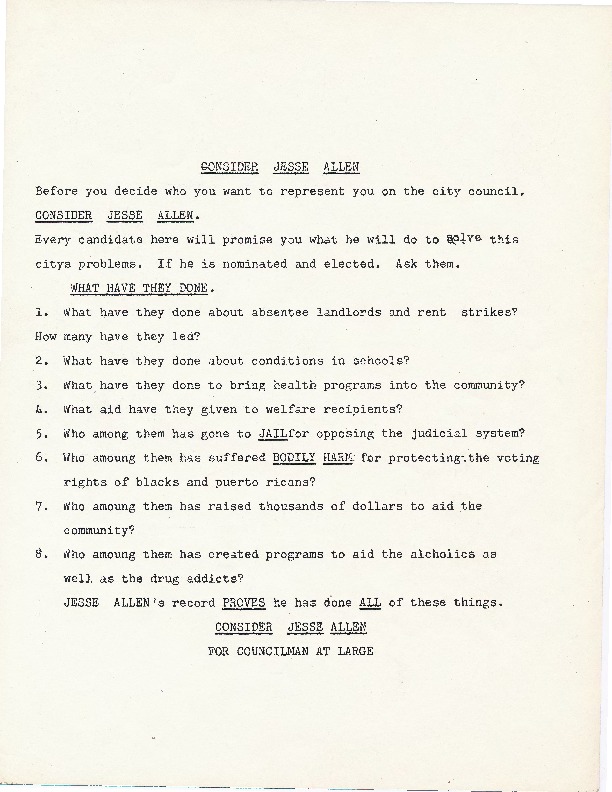

Leaflet from the Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention (1969) promoting the candidacy of Jesse Allen for Councilman-At-Large. Leadership experience gained through the UCC had significant impacts on the development of political leadership in Newark’s Black and Puerto Rican communities. Many UCC members, including Sharpe James, Jesse Allen, Donald Tucker, and Earl Harris went on to be elected to political office in Newark. — Credit: Junius Williams Papers

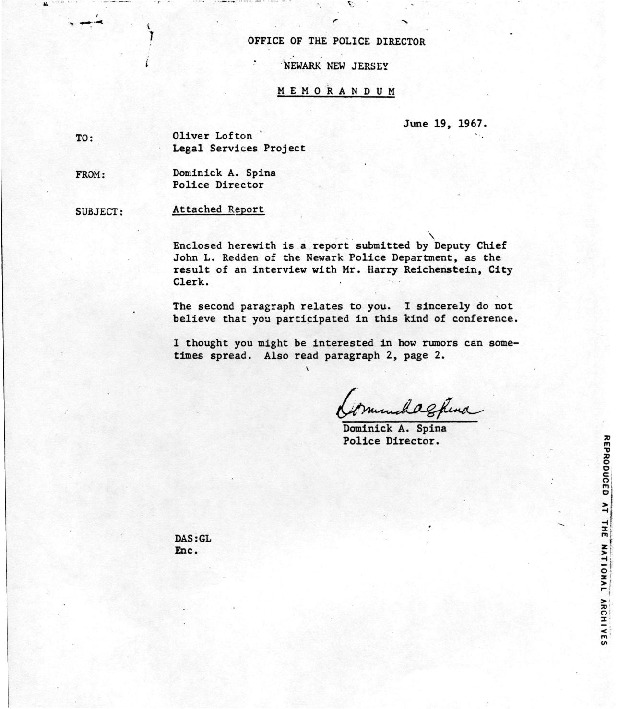

Police report forwarded to Newark Legal Services Project director, Oliver Lofton, from Newark Police Director Dominick Spina on June 19, 1967. The report was based on information provided by the City Clerk regarding alleged plans of the UCC Area Boards 2 and 3 to bring the Black Panthers to Newark. The report names several influential Black and Puerto Rican community leaders, including Lofton, Robert Curvin, Louise Epperson, Honey Ward, George Richardson, and Jesse Allen, as accomplices to a planned “revolt” by the “Spanish and Negro population” on June 27. The UCC and other community organizations in Newark were continuously subjected to official surveillance and later blamed for the outbreak of the 1967 Newark rebellion. — Credit: Junius Williams Papers