Puerto Ricans

“It is a piece of historic irony that in 1917, the year in which Congress passed the first of a series of laws designed to limit foreign immigration to (the United States), it also gave full citizenship to residents of Puerto Rico and thus paved the way for one of the most intensive periods of immigration in our nations’ history.”

Puerto Ricans came to Newark in the 1950s when there were jobs available in the city’s leather, brewery, iron and transportation industries. But jobs began to disappear in the 1960s when most of the older factories were closing. In the 1970s, New York Puerto Ricans began coming to Newark in search of housing and jobs, as well as from the island of Puerto Rico. The result was higher unemployment as the new arrivals were hampered by low skills and work experience and inability to speak English. Puerto Ricans were exploited for their cheap labor and discrimination was rampant. Puerto Ricans were citizens but treated as strangers in their own country.

In 1970, Dr. Hilda Hidalgo produced a study called “The Puerto Ricans in Newark, NJ”. She estimated the population at that time to be 45,000. She found that Puerto Ricans were “pushed to the USA by extreme poverty and lack of opportunity in Puerto Rico,” and articulated a pattern of cause and effect not unlike the situation of African Americans at that time, with the added burden of not speaking English.

Puerto Rican leadership began working in coalition with African Americans in the late 1960s. Neither group completely trusted each other for reasons beyond the scope of this brief introduction, but some attempts were successful to bring equity to both communities. For example, in the Medical School Fight, discussed in Chapter 3, African Americans were joined by Puerto Ricans in the fight to block removal of 20,000 blacks and Puerto Ricans from the path of the proposed College of Medicine and Dentistry in the Central Ward. And in the settlement of this conflict, African American leadership called for and set up training for black and Puerto Ricans to be hired on the medical school construction site. Puerto Ricans were instrumental in the success of the Black and Puerto Rican Convention, which nominated Ken Gibson to become the first African American mayor of Newark (1969); and voted for his election in 1970.

After the Rebellion in 1967, when the majority of white ethnic groups completed their march to the suburbs, African Americans and Puerto Ricans were the major resident groups left to contend with joblessness, poor housing, ineffective schools, racist police officers with little connection to Newark, and other large political institutions which were still controlled by the same people who left the city. Flash forward: In 1974, as the plight of this growing sector of the population continued to worsen, there was the inevitable clash between Puerto Ricans and the police that ended in violence, this time in Branch Brook Park… during the term of a black mayor, Kenneth A. Gibson. Mayor Gibson personally intervened and the immediate conflict was brought under control. However, the problems did not go away. In our next iteration, Newark beyond 1970, we shall see how the Puerto Rican community adjusted its political path to deal with its position of seeming invisibility, the continued ghettoization of the community, increased pressure from other Latino immigrants streaming into Newark; and the African American political establishment that grew strong enough to elect its own officials in 1970 and beyond.

However, the Puerto Rican community began organizing itself more effectively, with a massive voter registration drive, driven by a call for a united force. Social service agencies, schools, churches and civic organizations were engaged. Summer jobs became available for Latino youth; more appointments were made to municipal boards, and to the police department.

Puerto Ricans and other Latinos have been more active in the election process at the local and county level. They do not have the numbers alone to elect a Mayor, but there are Puerto Ricans on City Council. In coalition with other more recent Latino groups, with constituents who have become eligible to vote by naturalized citizenship, it will be possible to elect a Latino mayor in the very near future.

In general, however, Puerto Rican and other Latino communities have not overcome the stigma and discrimination attached to their points of origin and economic status. And so, unlike Europeans who came to the city and assimilated into a white majority, Newark’s Puerto Rican communities have not seen a wholesale improvement of their lot. There are many talented, well educated and successful Puerto Ricans in Newark and in the surrounding suburban communities, but like African Americans, as a group, they have been kept out of the American dream.

References:

Charles F. Cummings, Knowing Newark: Selected Star-Ledger Columns by Charles F. Cummings.

“Newark’s Puerto Ricans: Misunderstood Minority,” Four Corners, December 1962.

“Puerto Ricans in Newark: ‘All Rights of Citizens, Yet Considered Immigrants,” The

Star-Ledger, November 5, 1998.

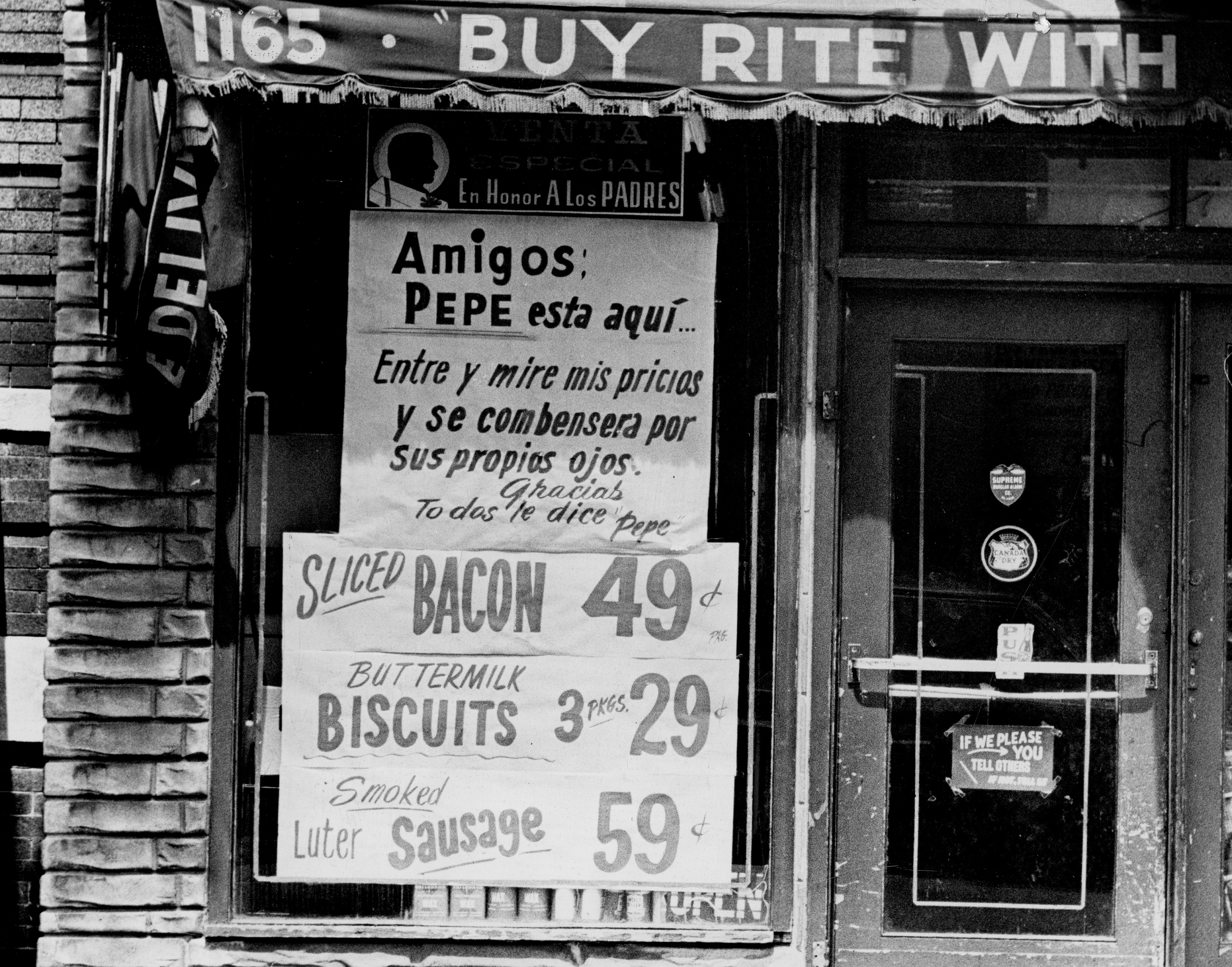

Storefront of a Puerto Rican-owned grocery store in Newark in 1966. — Credit: Newark Public Library

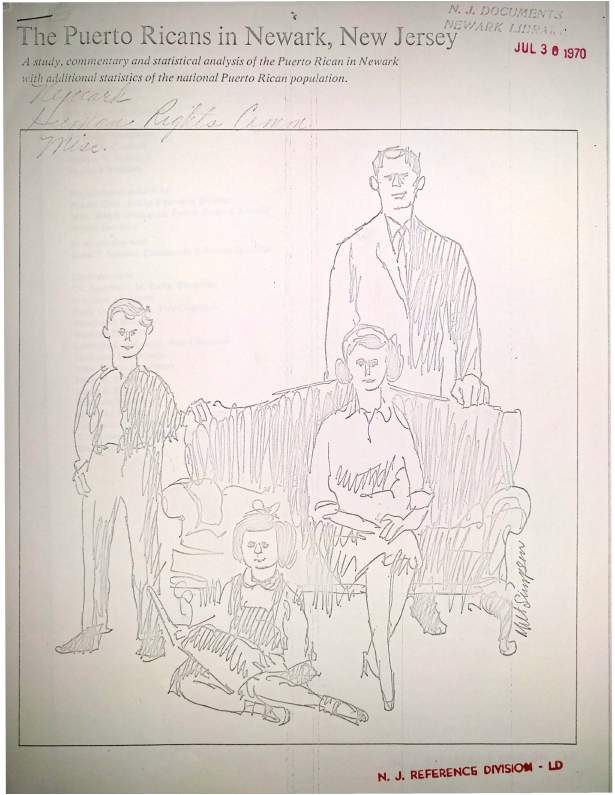

Published by the Newark Human Rights Commission in 1963, this report represents “a study, commentary and statistical analysis of the Puerto Rican in Newark with additional statistics of the national Puerto Rican population.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

Explore The Archives

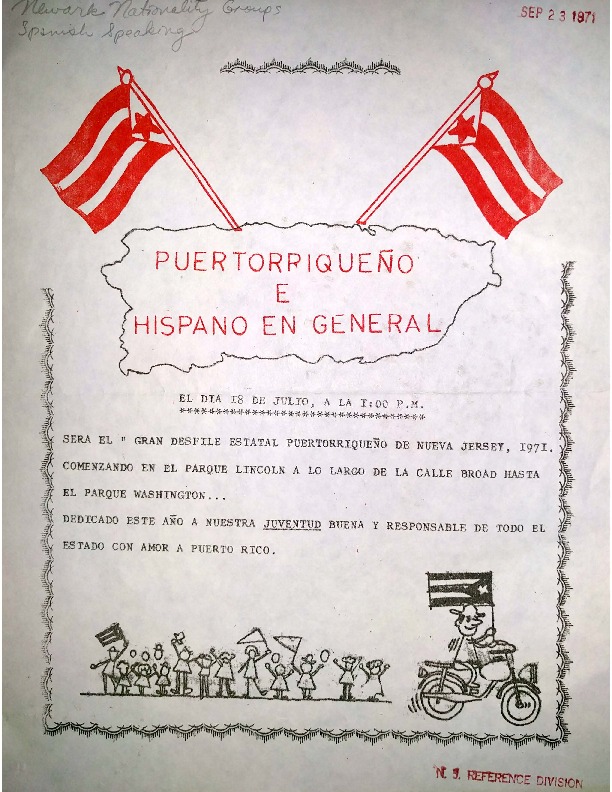

A look inside a Newark classroom in 1966, led by a Puerto Rican teacher. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Published by the Newark Human Rights Commission in 1963, this report represents “a study, commentary and statistical analysis of the Puerto Rican in Newark with additional statistics of the national Puerto Rican population.” — Credit: Newark Public Library