Black Business Development

In the late 1960’s, before the election of Ken Gibson as mayor, there was a groundswell of desire for Black economic development in the city of Newark. It was believed that if the economic conditions of Black communities were improved, all other conditions in these communities would improve as well. While economic nationalism was a core component of the Black Power movement, Black capitalism was propped up by the Nixon administration as a means of bringing Black people into the fold of the American economy, thereby siphoning support from the Black Power movement’s critique and challenge of capitalism. These dueling interests in economic development brought together a diverse group of Newark’s community leaders in the late 1960s and early 1970s to promote Black economic development. One of the early efforts in this regard was the creation of the private non-profit consulting organization, the Interracial Council for Business Opportunity (ICBO) in 1966.

In the wake of the 1967 Newark Rebellion, ICBO made working capital available to Black entrepreneurs to help them establish and operate their own businesses, along with legal, accounting, and financial guidance. Based on a survey assessing the credit needs of Newark’s “ghetto businesses,” Fidelity Union Trust Company, First National State Bank of New Jersey, National Newark & Essex Bank, and the Bank of Commerce collectively contributed $1 million over a one year period to the ICBO. The ICBO was coordinated through the offices of the Greater Newark Urban Coalition, whose President Gustav Heningburg stated that “ghetto businessmen” who demonstrated that they couldn’t get financing elsewhere would qualify for the special loans under “liberal” standards that would be set. He further commented that the ICBO program was an “artificial process to set a record of good credit for ghetto businessmen who will more than likely become regular customers of the bank.”

The program was designed to support job development and allow “money injected into the economy of the ghetto to be spent and re-spent within the ghetto within a new structure of business activity.” Shortly after the creation of ICBO, Heningburg applied to the Economic Development Agency of the U.S. Department of Commerce for $330,000 to create what he called a “black business community in Newark.” According to Heningburg, the Minority Economic Development, Industrial and Cultural (MEDIC) Enterprises, Inc., a non-profit cross-section of Newark’s Black community, was formed to purchase companies and turn over complete control to Black people, instead of just creating businesses to employ Blacks. This was an important step for the community, Heningburg contended, because “without equity of ownership, management or control, the minority community is powerless to improve its own status…This non-white community remains only a consumer, an outsider completely bypassed by the commerce of the community; straight men through which the money flows right back to the white community.”2

Federal funds, as well as additional local funds from the Urban Coalition, were earmarked to purchase businesses agreed upon by MEDIC’s 30-member board of directors. Once created, residents could then be trained and employed by the newly formed black businesses. By 1970, MEDIC-supported businesses included a plumbing and heating company, theatre company, printing company, limousine company, dressmaker, pharmacy, and supermarket.

Such stimulus to Black economic business development, however, was not without its challenges. Some city officials, at the time, expressed a level of skepticism about the creation of MEDIC. Under then Mayor Hugh J. Addonizio, Newark Office of Economic Development Chief P. Bernard Nortman raised questions about the proposal, while Newark Community Development Administrator Donald Malafronte said that it was “unusual for an Urban Coalition to seek federal funds, rather than raise funds from business.” Furthermore, after the U.S. Secretary of Commerce’s visit to Newark in 1970, MEDIC appeared to have received more requests for assistance from the community than they could handle without receiving much tangible support from the federal government. In response to that visit, it was noted in MEDIC’s First Progress Report that “the visit and promises from the White House ended up as a public relations gimmick with the only tangible community benefit being a library or information center and a sign over our door.”

Concerned with issues of sustainability of Black-owned businesses, Dairy Williams, Vice-Chairman of MEDIC and Executive Development Director for the Urban Coalition, resigned from the Urban Coalition to form the Ebony Business Men’s Association, a group of more than 100 Black business men pooling their resources and knowledge together to improve Black businesses. Due to Black entrepreneurs’ lack of experience, Williams believed that it was important to stress education. In his view, “blacks had to help themselves and not depend on the government or groups.”

Despite the skepticism, when US Secretary of Commerce Maurice H. Stans came to Newark in 1970 under the first administration of Mayor Kenneth Gibson, to designate MEDIC as an affiliate of the Office of Minority Business Enterprise (OMBE), MEDIC was to become a “one stop shopping center.” Located on Washington Street, MEDIC was to be resourced with brochures and booklets from the OMBE and armed with an increased capacity to assist minority businesses with managerial and technical assistance. According to MEDIC’s Report, OMBE was also to provide a team to work with MEDIC to solicit additional support from businesses and corporate leaders. OMBE awarded MEDIC $132,295 in order to bring more “black capitalism into the mainstream of America’s economy.” In addition, the Minority Enterprise Small Business Investment Company (MESBIC), a federal version of MEDIC, pledged to have $375 million in capital available for minority businesses by 1971 and the Small Business Administration would guarantee additional loans to start-up businesses backed by MESBIC.

As a result of this influx of financial and technical support, Secretary Stans noted that 112 minority enterprise loans had been approved in the amount of $2.8 million. Recipients of this support included Father and Son’s Seafood Restaurant & Catering on Nye Avenue, Harrison’s Pharmacy on High Street (now MLK Blvd), and the Tri-Cities Limousine Service. MEDIC supported a variety of projects including the potential purchase of a bank, cable television station, and the WNJR radio station. MEDIC would eventually be labeled as a “funneling agency” for funds from the federal Office of Minority Enterprises.

References:

Star Ledger, “$1 million in aid for businessmen”, October 6, 1968.

Star Ledger, “Newark group seeks aid for businesses”, December 6, 1968.

MEDIC Enterprises, Inc., First Progress Report, September 26 – December 31, 1970.

Star Ledger, “Newark agency gets funds for black capitalism”, October 6, 1970.

Star Ledger, “Black businessmen unite for strength”, April 5, 1970.

Star Ledger, “Newark group wins grant for urban project”, December 22, 1971.

Annual report of the Greater Newark Urban Coalition for 1969, which includes progress reports on various initiatives to support Black businesses. –Credit: Newark Public Library

In this clip from a 2009 oral history interview conducted by Bob Curvin, Ken Gibson discusses his relationship with the Newark Police Department and his decision to appoint John Redden during his first term. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

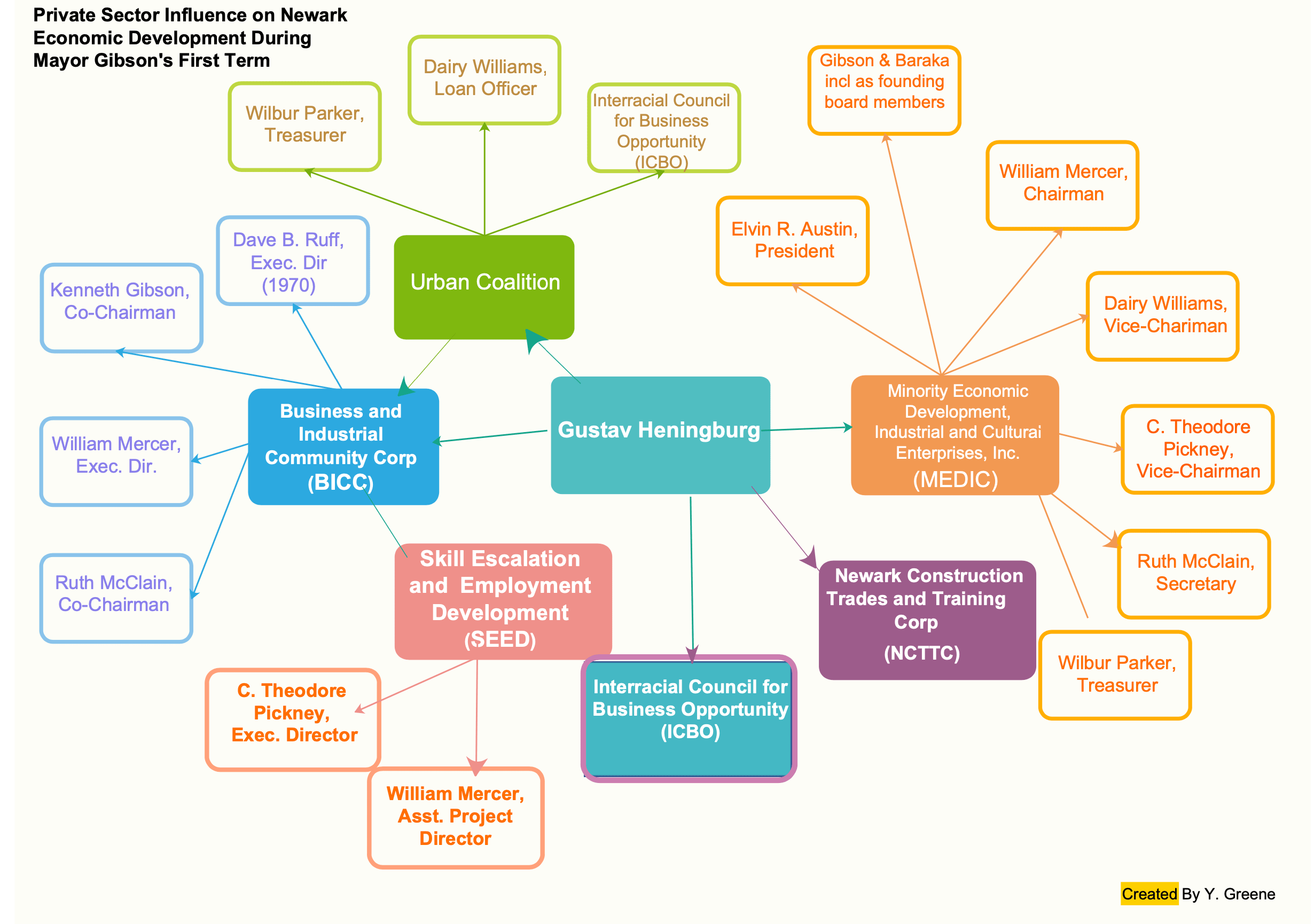

This map illustrates the relationships between different organizations and individuals involved in supporting Black business development in Newark. –Credit: Yolanda Greene

First progress report of MEDIC, covering the months of September through December 1970. The report includes a summary of activities, inquiries for support, and an overview of MEDIC projects. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Lorenzo Pryor, member of the Ebony Business Men’s Association, posing inside IGA Supermarket, which he founded as Newark’s first Black owned and operated supermarket. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Clip from a 2020 interview with MEDIC Secretary Ruth (McClain) Rambo, in which she reflects on her involvement with MEDIC in the early 1970s. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Explore The Archives

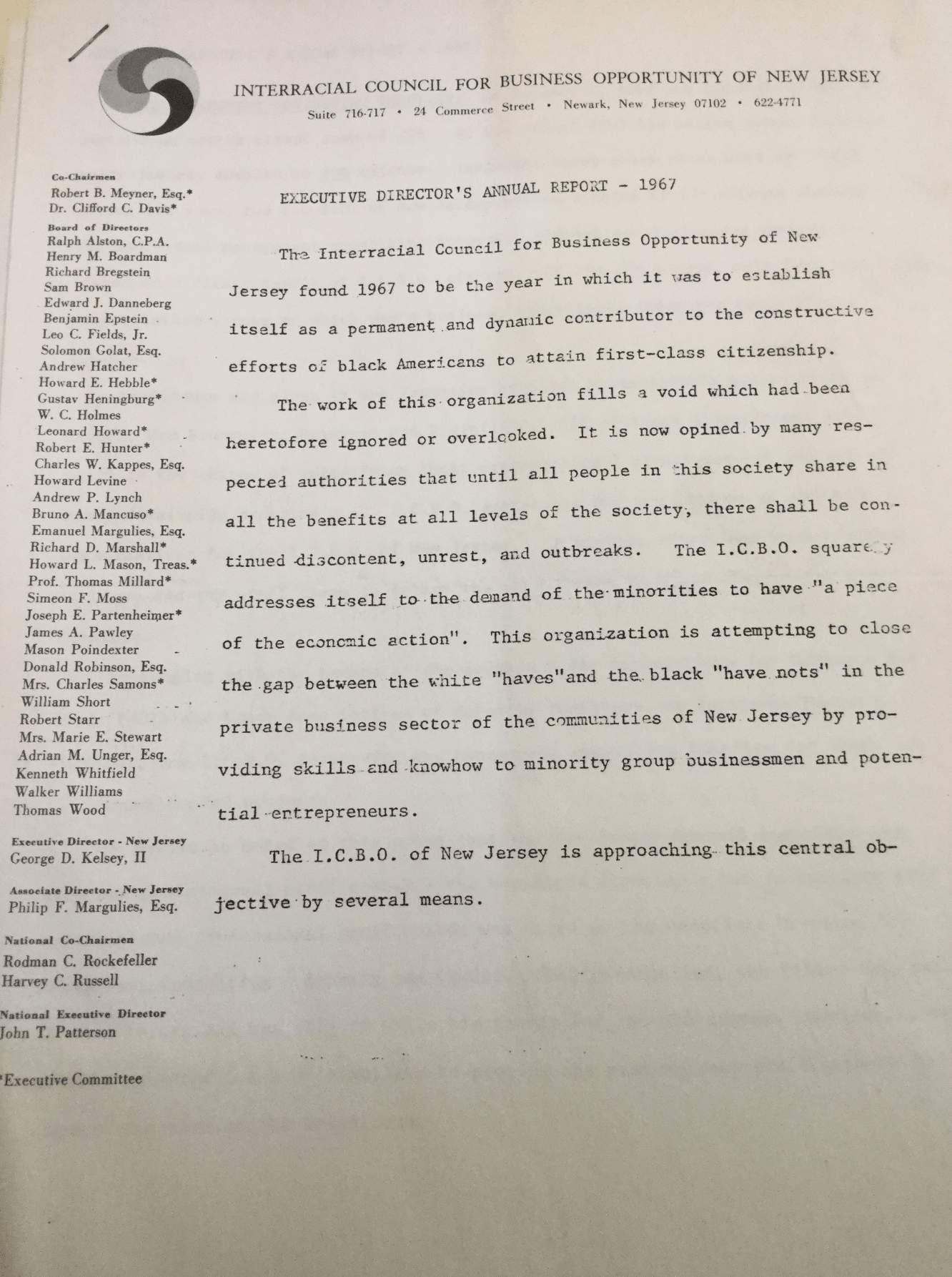

Annual report of the Interracial Council for Business Opportunity of New Jersey for 1967, which describes the core functions and progress of the ICBO. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Ted Pinckney discusses his involvement with the Business Industrial Coordinating Council (BICC) and Interracial Council for Business Opportunity (ICBO) in the late 1960s-early 1970s. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

A description of the current and proposed program activities of the ICBO of Greater Newark from September 1966. –Credit: Newark Public Library

An explanation of the proposed budget of the ICBO for 1967, including an overview of the main programmatic expenses. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Ruth (McClain) Rambo discusses her involvement with the Greater Newark Urban Coalition in the 1960s-70s. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

A memo from Board Chair William A. Mercer to members of the MEDIC Board of Directors, January 27, 1971. –Credit: Newark Public Library

By-Laws of MEDIC Enterprises, Inc., outlining the structures and responsibilities of the organization. –Credit: Newark Public Library

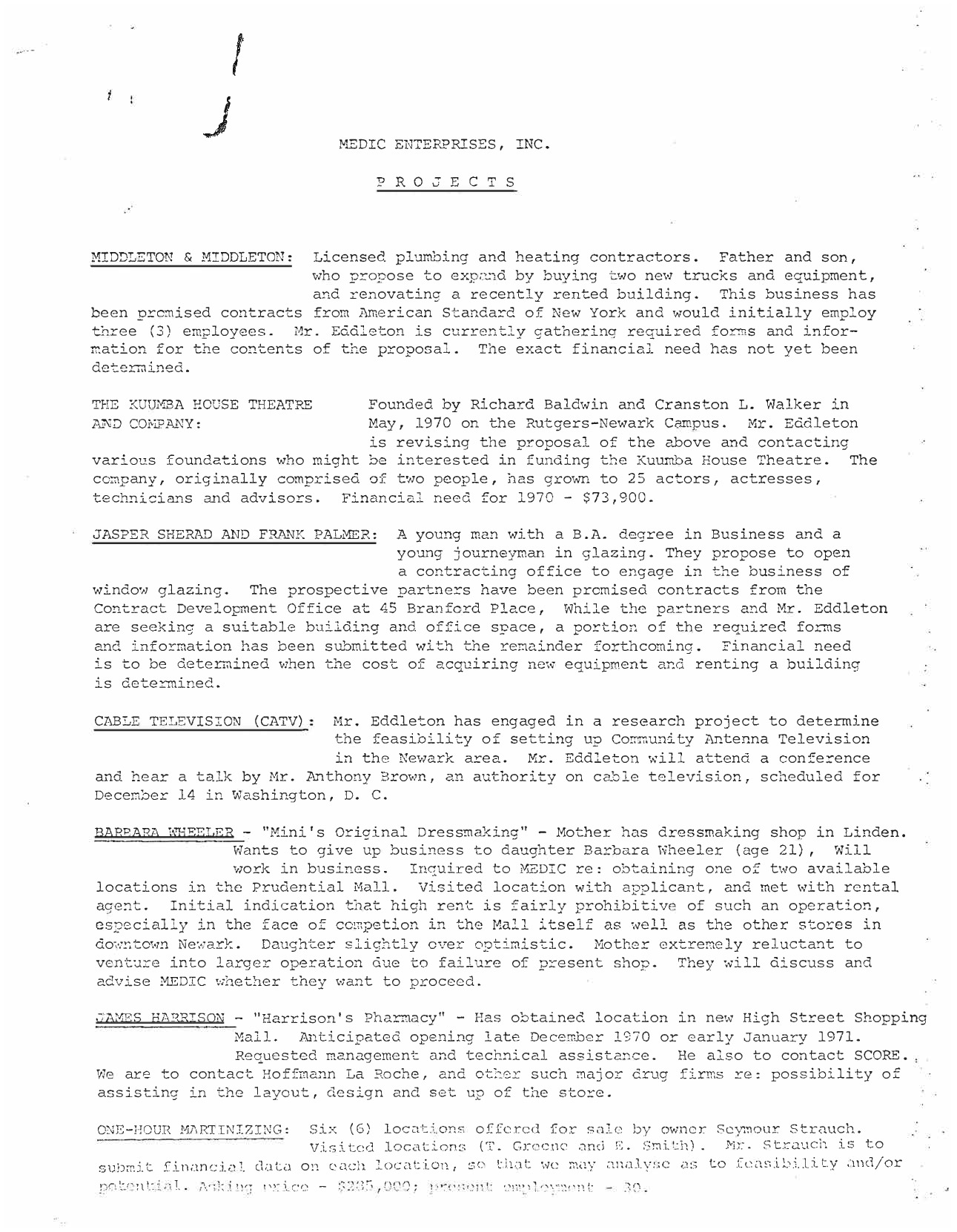

A list and overview of MEDIC sponsored projects, created on December 9, 1970. –Credit: Newark Public Library

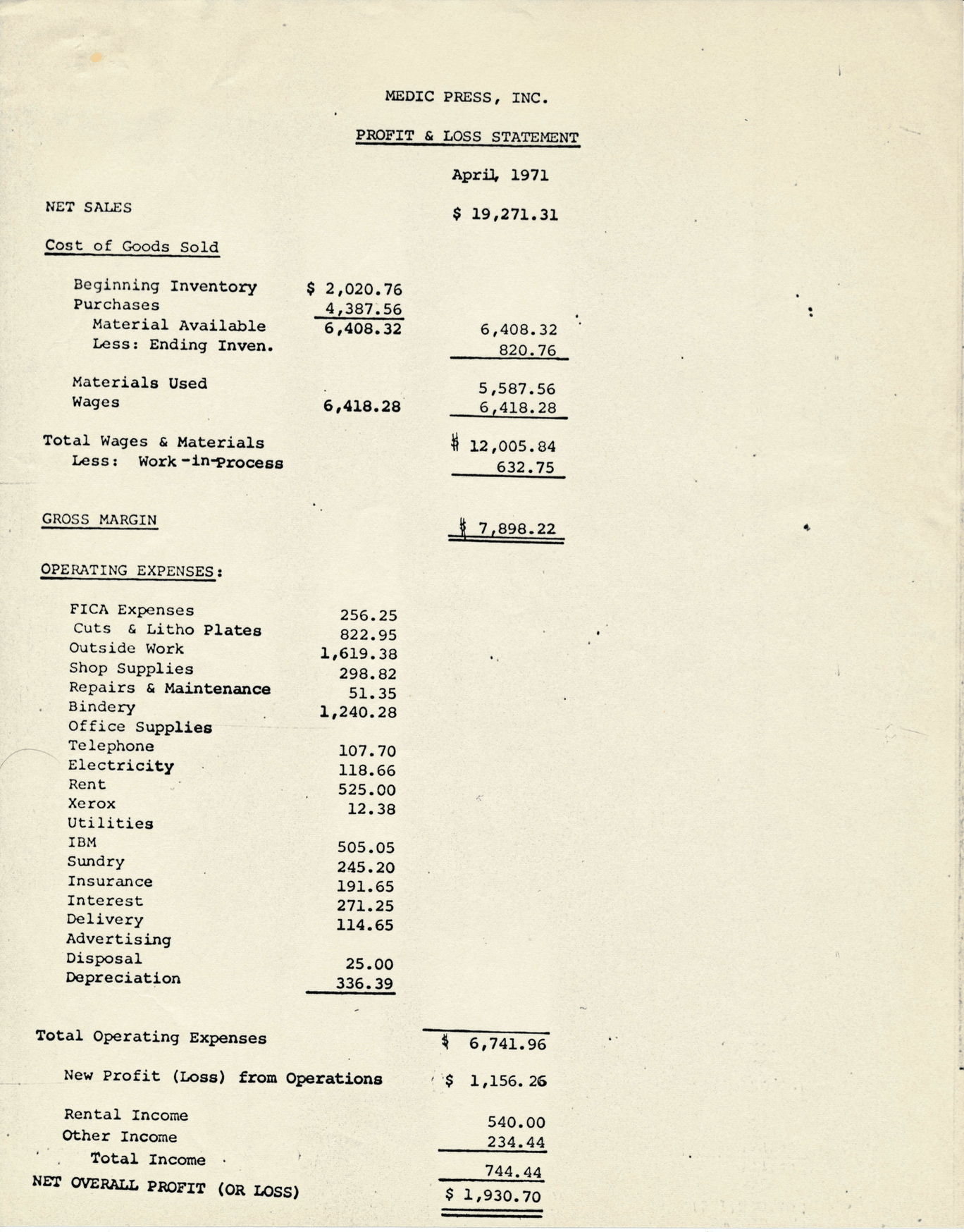

A statement of profits and losses for MEDIC Press, Inc. as of April, 1971. –Credit: Newark Public Library

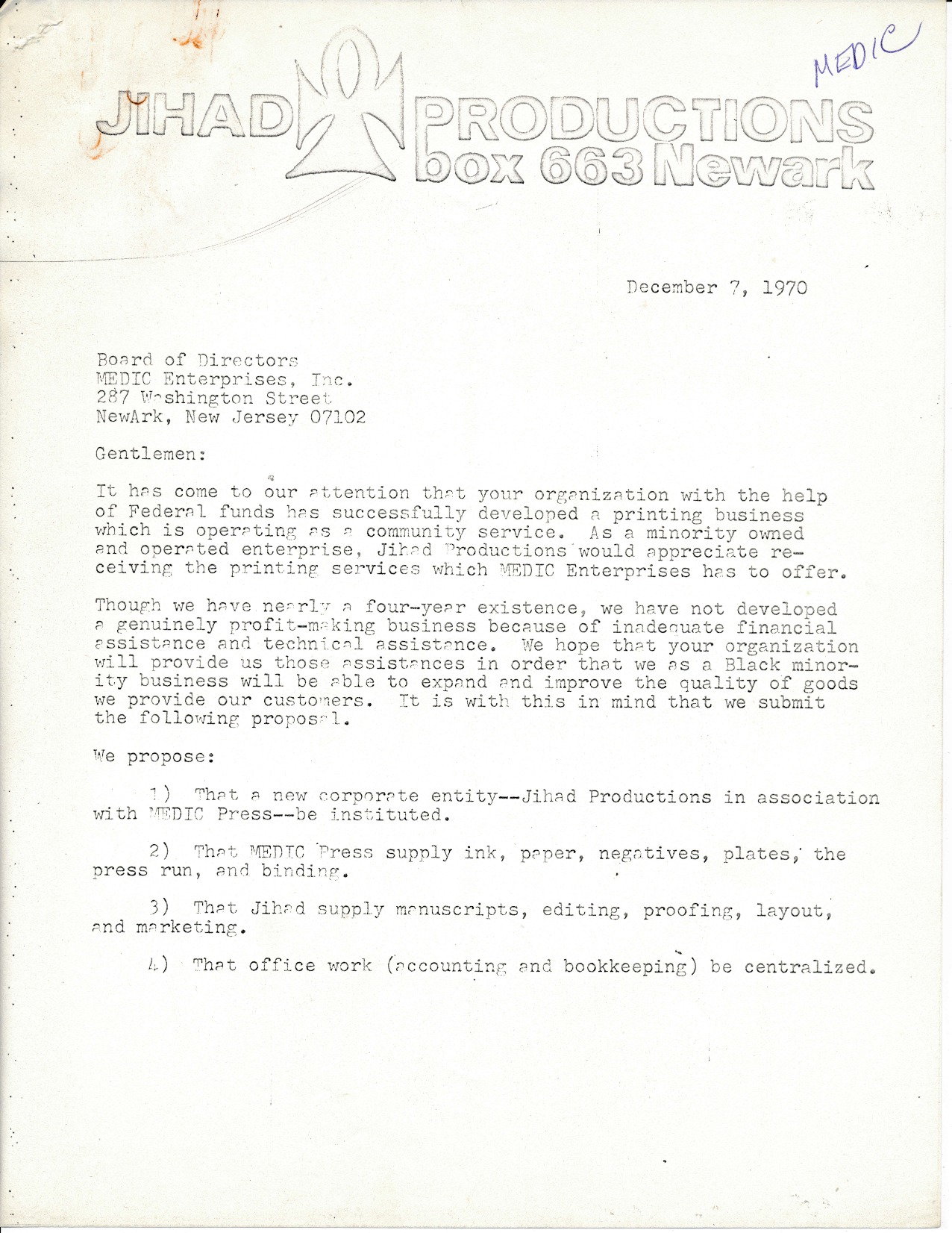

Letter from Jihad Productions to the MEDIC Board of Directors, December 7, 1970. The letter proposes a partnership between Amiri Baraka’s Jihad Productions and MEDIC Press. –Credit: Newark Public Library

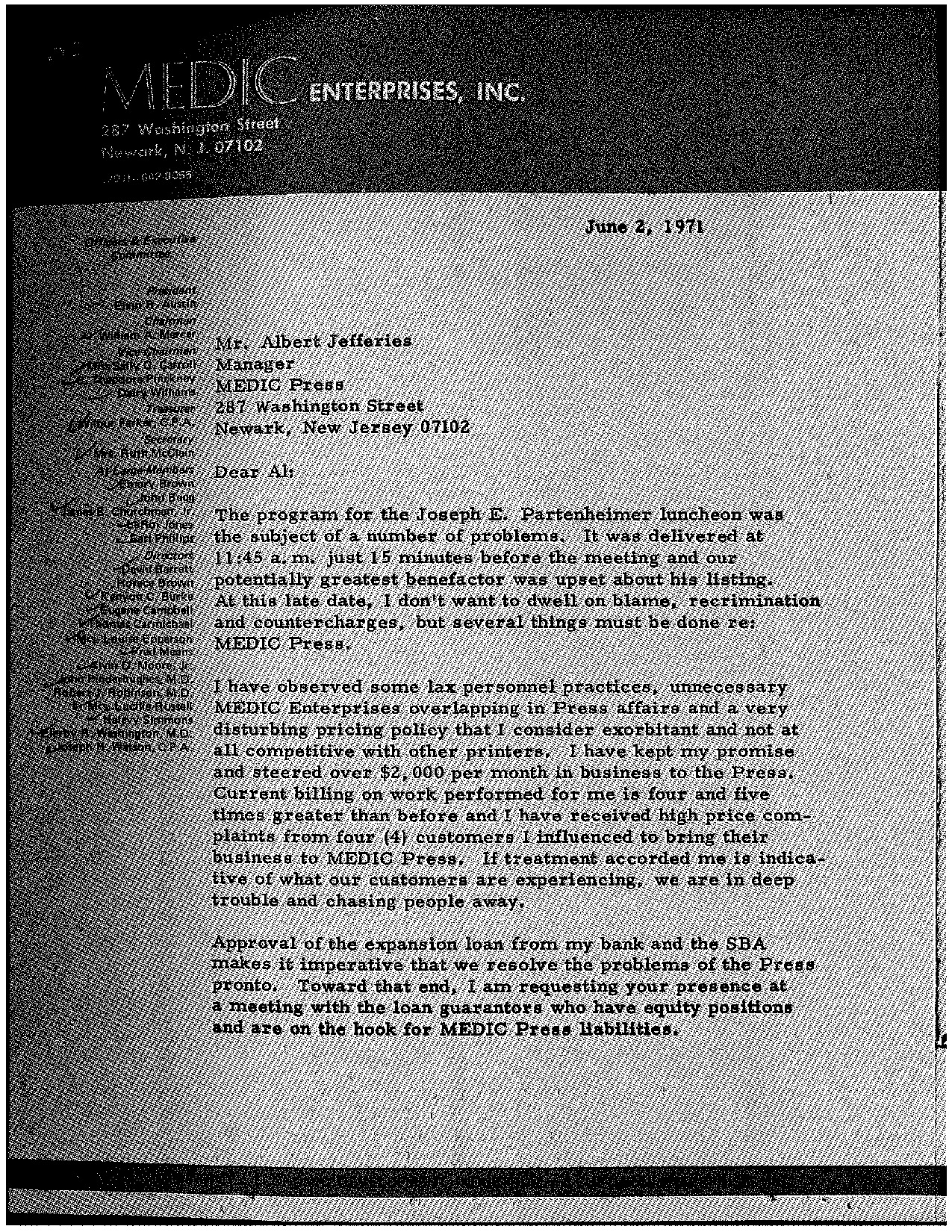

Letter from MEDIC Board Chair William A. Mercer to MEDIC Press Manager Albert Jeffries, June 2, 1971. –Credit: Newark Public Library

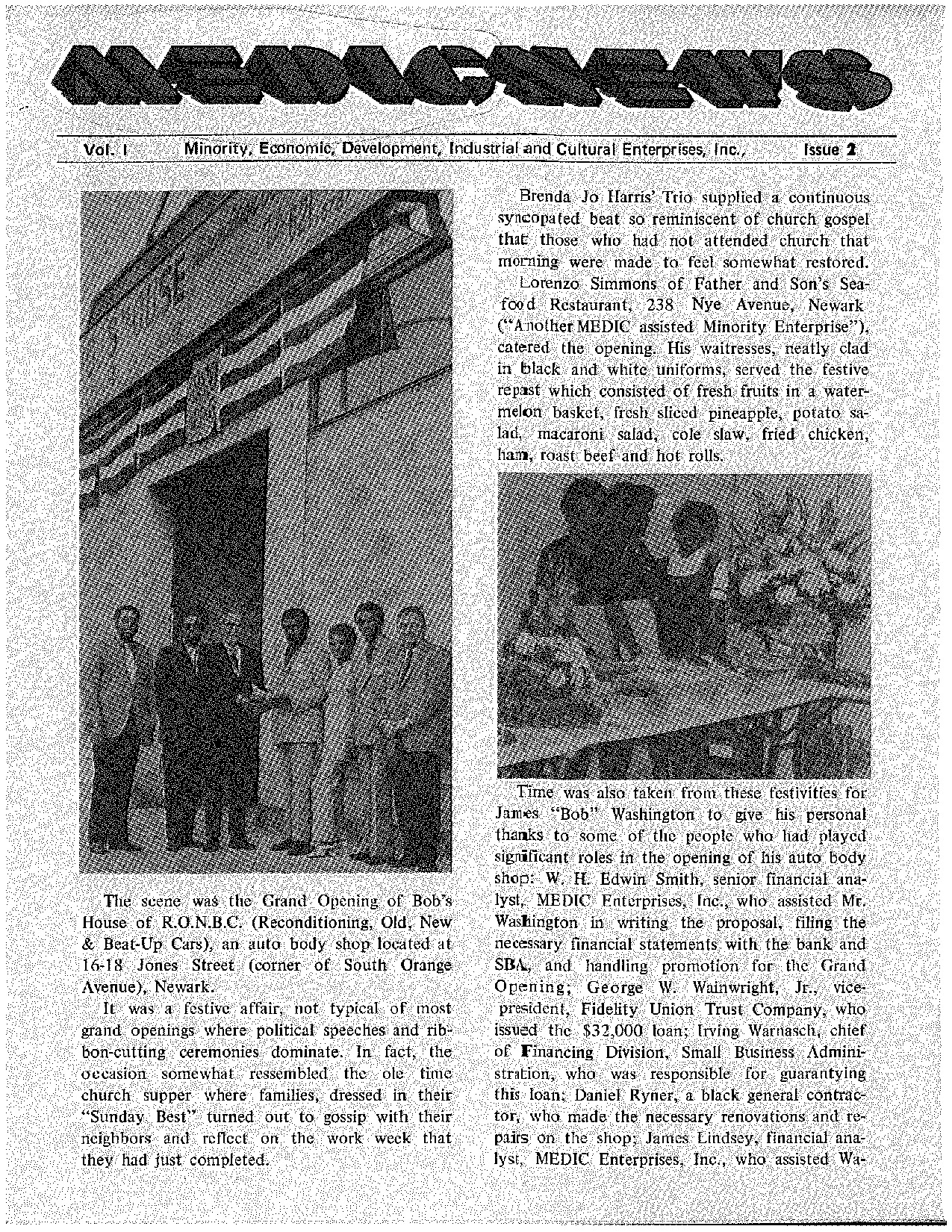

Volume 1, Issue 2 of MEDIC’s newsletter, MEDIC News, published in 1971. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Minutes of the MEDIC Board of Directors meeting, November 11, 1970. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Minutes of the MEDIC Board of Directors meeting, January 20, 1971. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Minutes of the MEDIC Board of Directors meeting, April 14, 1971. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Minutes of the MEDIC Board of Directors meeting, June 9, 1971. –Credit: Newark Public Library

The first issue of MEDIC’s newsletter, MEDIC News, published in 1971. The newsletter includes an overview of MEDIC history and coverage of its programs and initiatives. –Credit: Newark Public Library