African Americans, Pt. 3 (First Great Migration)

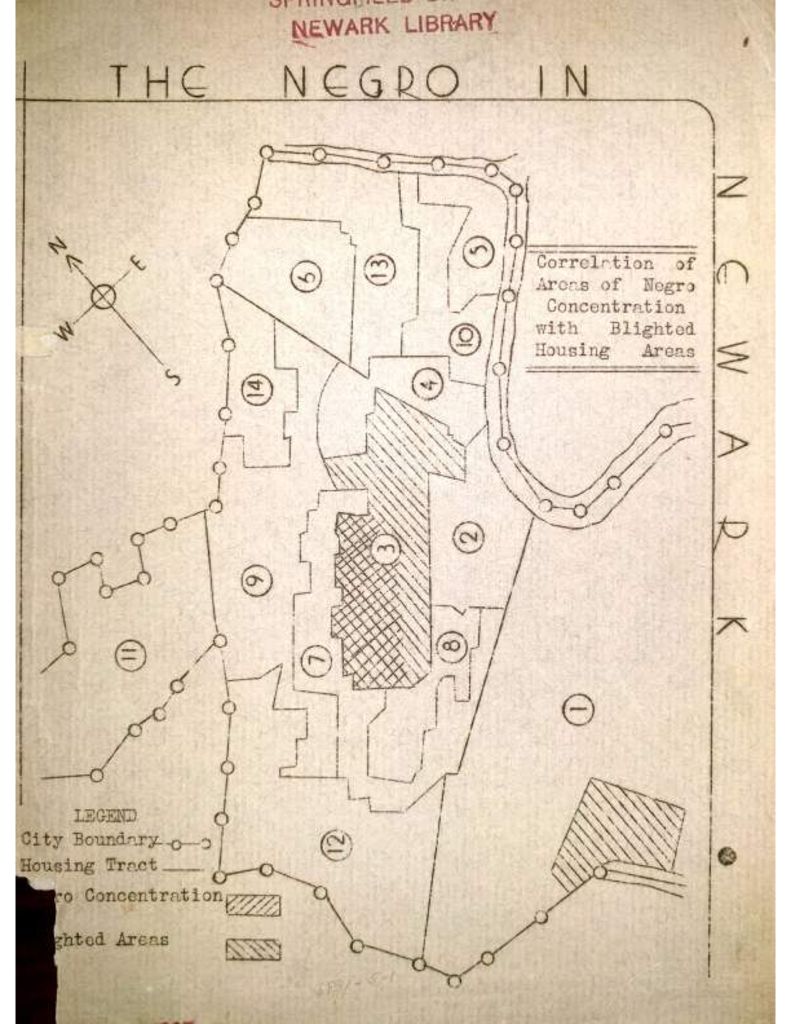

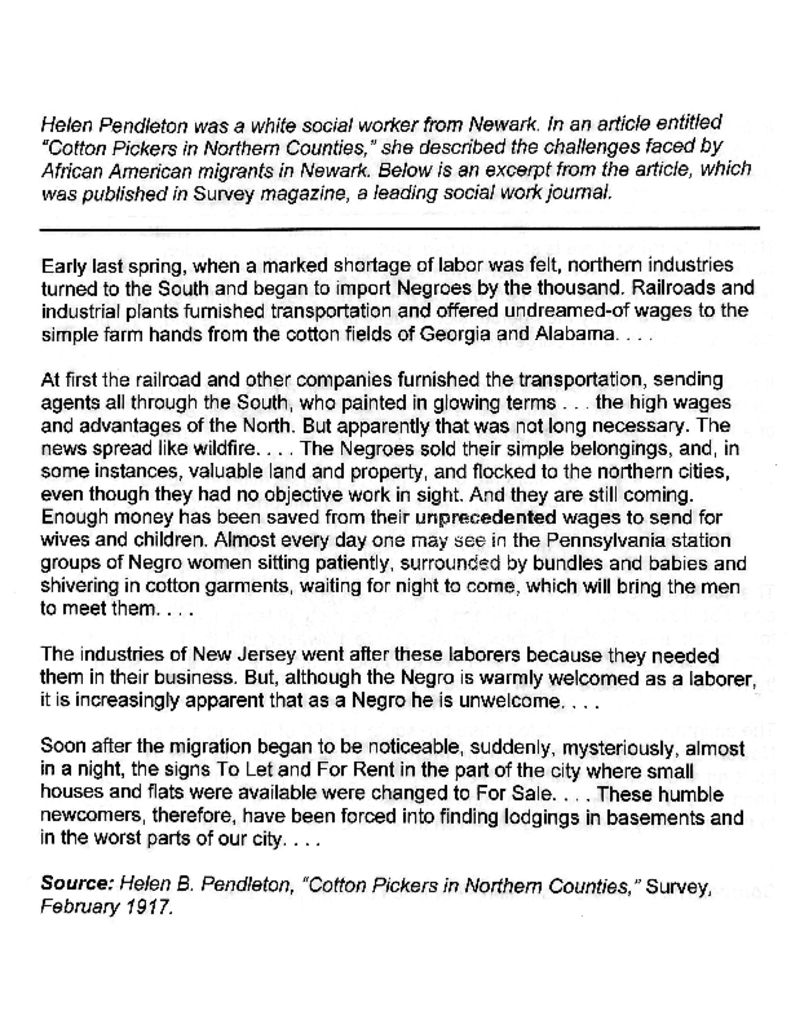

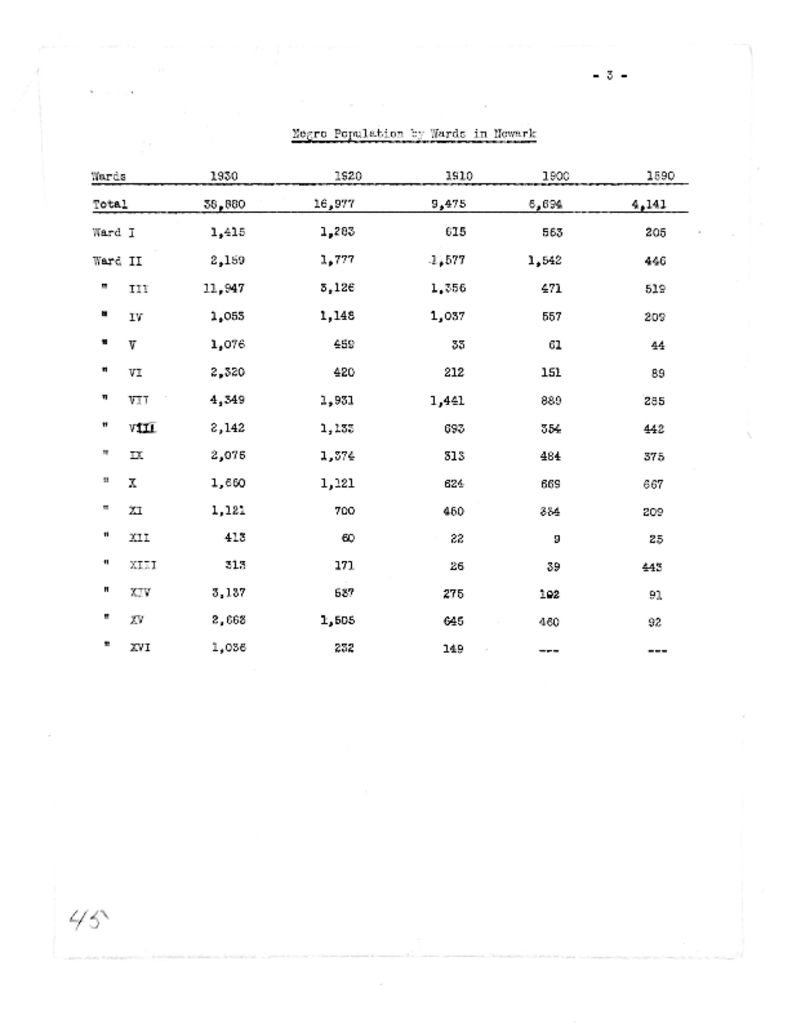

Newark became the destination of thousands of African Americans fleeing the Southern states for better jobs and freedom from Jim Crow segregation and violence. The black population grew from 9,475 in 1910, to 38,880 in 1930. Despite a Newark Evening News editorial claiming there was no “Negro Problem Here,” this new group of immigrants encountered many problems in Newark. Housing was run down and racially segregated. Before 1910, African Americans lived all over the city. But with the migration, they were confined mostly to the Old Third Ward (now the Central Ward of Newark), paying high rents for slum housing. Disease flourished, crime rose; police were more violent in the black community than in other neighborhoods. By 1940, the Third Ward contained more than 16,000 black residents, living in houses where outside toilets were still in use. It was the beginning of the modern day ghetto.

The migrants found jobs in the existing industries doing jobs at the bottom of the economic ladder, and in some low-level government jobs. The skilled jobs were especially out of reach for African Americans. Black laborers were barred from most labor unions. A rigid color line was maintained in most industries to prevent trouble with white workers. It was more practical to hire blacks as janitors, porters, cleaners, or furnace men—jobs for which white people thought African -Americans were suited.

The Rise of Black Institutions

But in the 1920s and 30s, some 300 blacks went into business for themselves.

These businesses included restaurants; taverns; bakeries; barber shops; beauticians; funeral businesses; and trucking firms. Black people started a bank (The People’s Finance Corporation) and several professional associations (for funeral directors, beauticians, and barbers). They engaged in commerce with white suppliers, complied with local laws for licensing, zoning and regulations, and pursued their economic interests, as did other ethnic group entrepreneurs. Although a black economic base was taking shape, Dr. Clem Price said, “There is little indication that blacks were permitted to participate in Newark’s social and political life,” and less evidence that they wanted to develop a strategy for uplifting the masses in the face of a restrictive system of Jim Crow.”

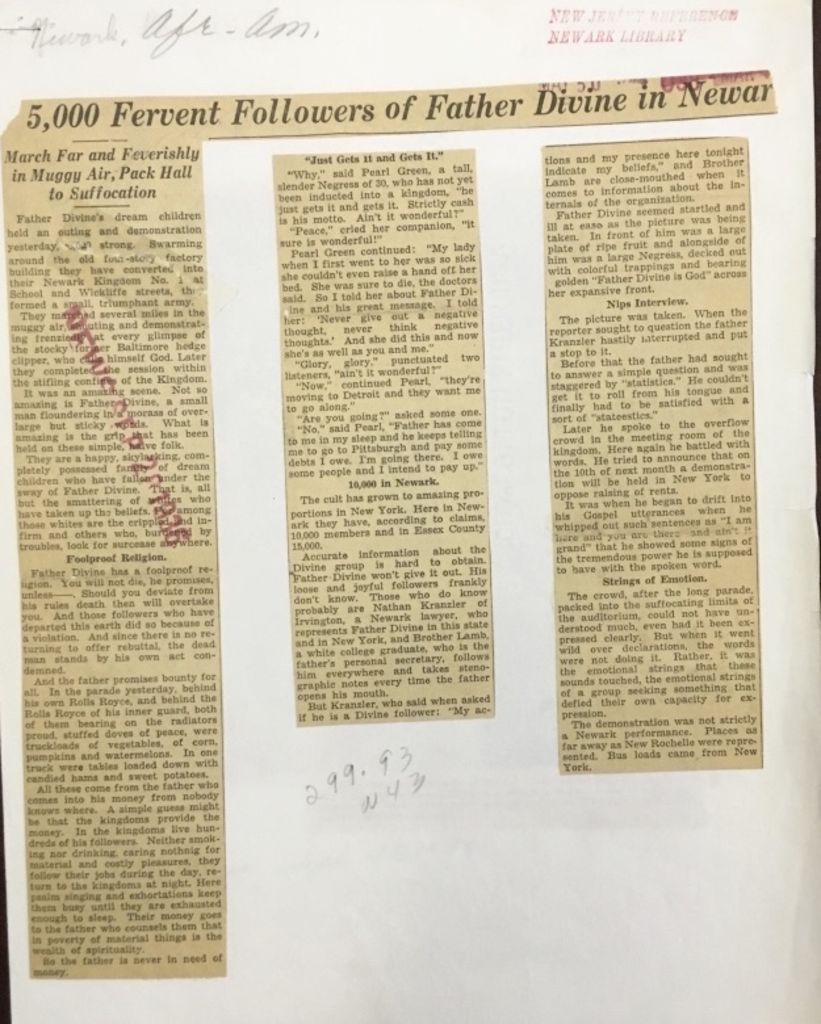

Churches filled the void where help was needed. There was a rise in the number of black churches of all denominations, where Gospel music had a profound influence on the congregations and throughout the nation. In 1913, the Moorish Science Temple of America was formed in Newark by Noble Drew Ali. It is a direct precursor to Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam. Father Divine set up his own independent church, attracting thousands of followers. In Newark he set up three missions of the Kingdom in addition to a large building on Central Avenue, an the impressive 8-story, 250 room Divine Riviera Hotel on Clinton Avenue and High Street (now Martin Luther King Blvd), which is operational even today.

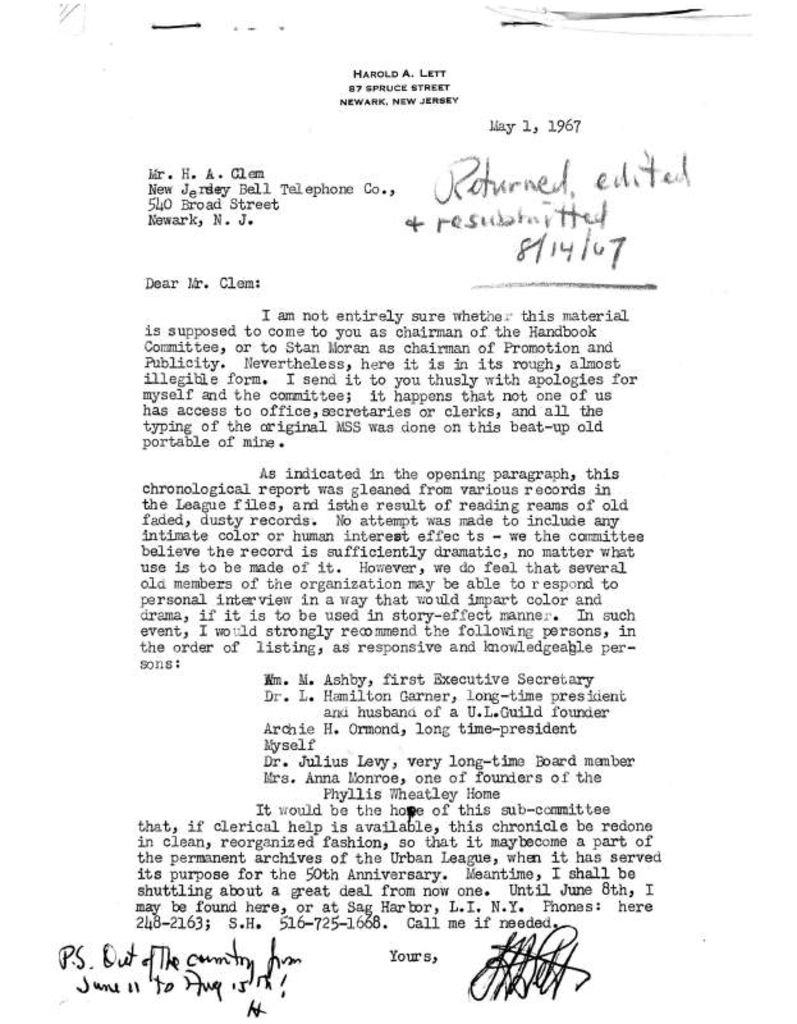

Community organizations, such as the NAACP and Urban League, sought to help the immigrants. The NAACP led a silent protest march of more than 2,000 people down Broad Street for better housing and civil rights; Prosper Brewer, a Republican power broker in the Third Ward, organized a dock workers strike at the Port of Newark to demand higher wages; the Urban League, founded in 1917, sought to find jobs for the people; Friendly Neighborhood House opened in 1926 to offer social services to the new black immigrants. And Marcus Garvey’ Universal Negro Improvement Association set up a chapter in Newark in 1921. Newark’s African Americans were undergoing an awakening.

Although Newark’s growing black populations were quickly developing institutions in the city, the Great Depression in 1929 was devastating to the African American community. “Last hired, first fired” prevailed, along with a preference for white immigrant groups over the people of a darker hue. This blow to the African American community’s economic base presented a major setback to black empowerment in Newark.

The Black Press

“The protest against racial injustice…during this period was greatly stimulated by the growth in the number of black newspapers. Between 1900 and 1940, (throughout the state), the number of newspapers rose from 12 to approximately 35. The state’s most widely circulated black weekly, the New Jersey Herald News, (later, the Newark Herald News) symbolized the contributory role of the press in the growth of protest.”

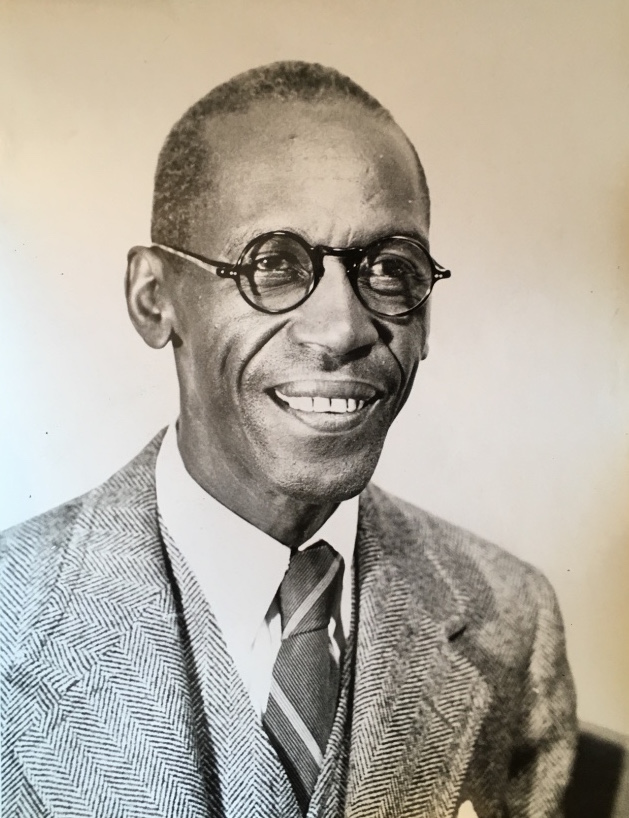

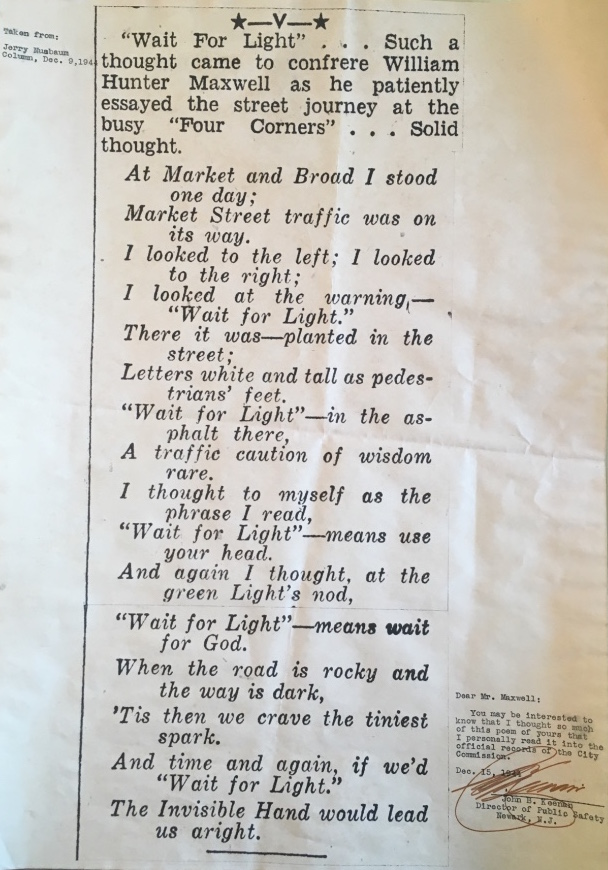

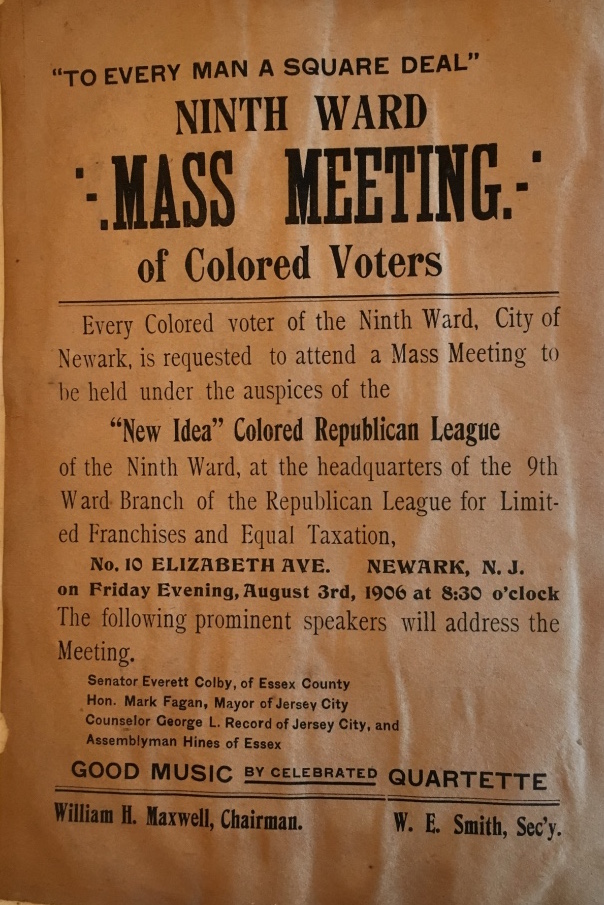

The paper was the product of the mind of William Maxwell, who moved to Newark in 1902 from Knoxville, Tennessee. He was the Sunday News Editor of the Newark Ledger, the first African American to hold such a position. But his passion was to stimulate self-help among black people, and to mobilize black people in and around Newark for black causes. He formed or helped form numerous political organizations, such as the Negro Progressive Republican League, and the Young Men’s Colored Republican Association of the City of Newark, but his greatest achievement was the Herald. His banner headlines got the attention of his customers (who were his constituents as well): “Poor Housing Conditions are Assailed in Englewood”; “Negro Must Use Politics to Win Rights”; “Negroes Shun ‘Jim Crow’”.

Clem Price said, “Had not the black press in New Jersey dramatized the grievances and aspirations of the race, civil rights activities would have been without a powerful voice on behalf of their movement.”

Black Power

A new political awareness began to grow, and the 1920s through 1940s saw the beginning of black political power on the local scene, in part personified by the election of Oliver Randolph in 1922 to the NJ State Assembly. And in 1927, the Community Hospital was established, staffed by black doctors and professionals. The black community was large enough to establish and sustain certain kinds of institutions in the face of racial discrimination.

References:

Robert Hill, ed. The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, Volume IX

Audrey Faulkner, et al., When I Was Comin’ Up: An Oral History of Aged Blacks

Kevin Mumford, Newark: A History of Race, Rights, and Riots in America

Clement Price, Freedom Not Far Distant: A Documentary History of Afro-Americans in New Jersey

Giles R. Wright, Afro-Americans in New Jersey: A Short History

William C. Wright, “The Beleaguered City as Promised Land: Blacks in Newark, 1917-47,” in Urban New Jersey Since 1870

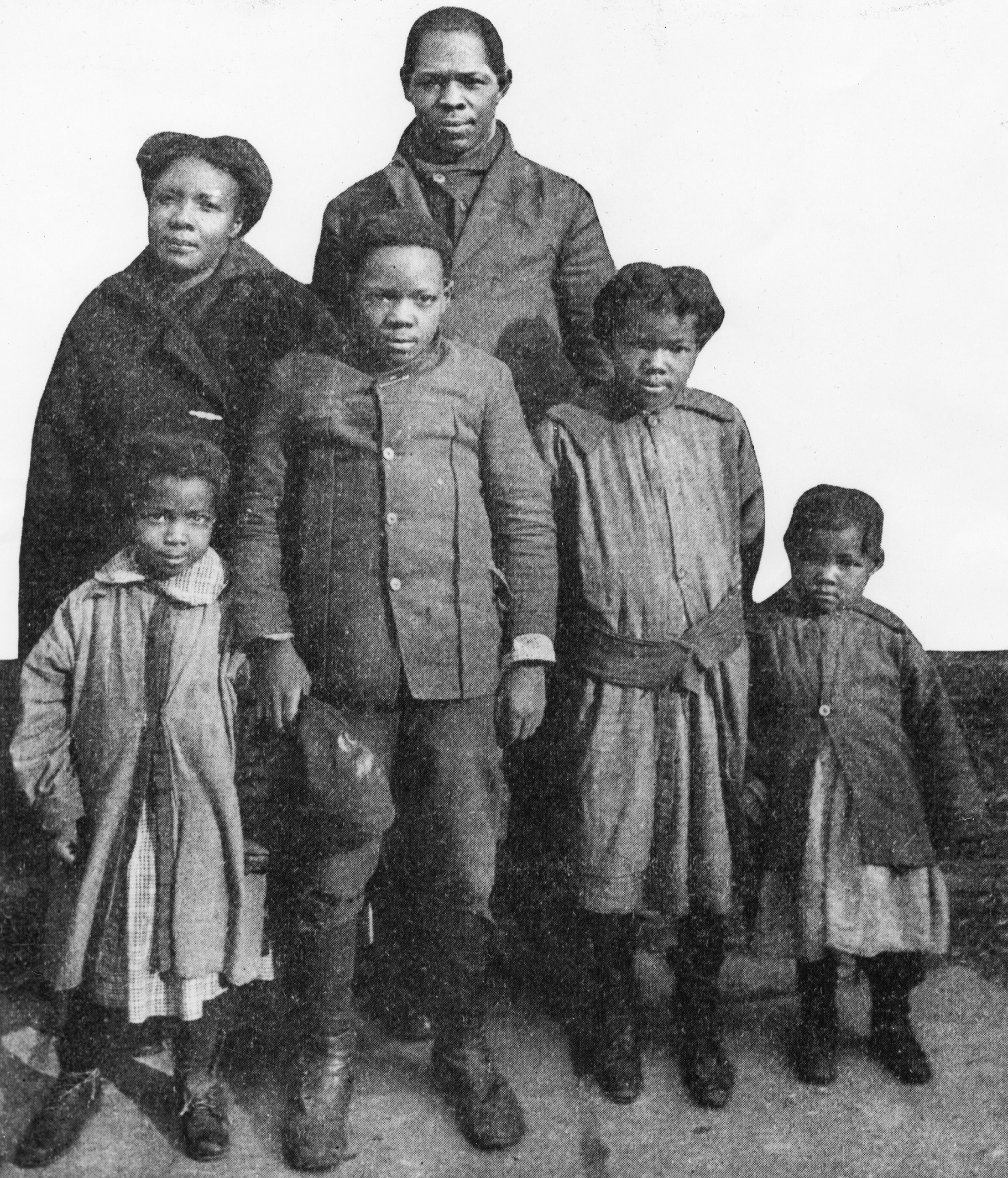

Photograph from Survey magazine of an African American family that migrated from the South to Newark during the First Great Migration. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Report by the Newark Interracial Commission in the 1930s describing the conditions faced by African American migrants in Newark. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Photograph of a congregation on the steps of the Moorish Science Temple in Newark in 1928. — Credit: Newark, NJ Memories Facebook Page

Photograph of William Maxwell, an influential political figure in Newark in the early 1900s. Maxwell was the first African American to be an editor of the Newark Ledger and active in numerous political organizations in the city. — Credit: New Jersey Historical Society

Explore The Archives

Article from Survey magazine describing the challenges faced by African American migrants in Newark during the First Great Migration. — Credit: Stanford History Education Group

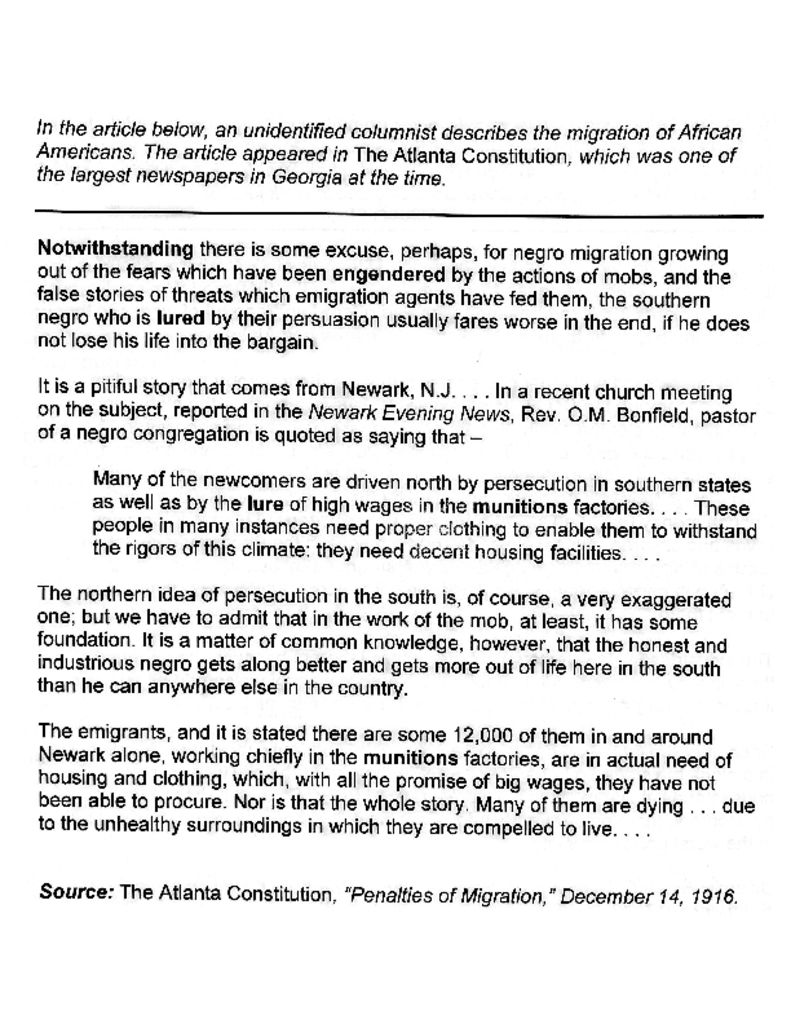

Article from The Atlanta Constitution describing the migration of African Americans from the South to Newark and the troubles faced in the North. — Credit: Stanford History Education Group

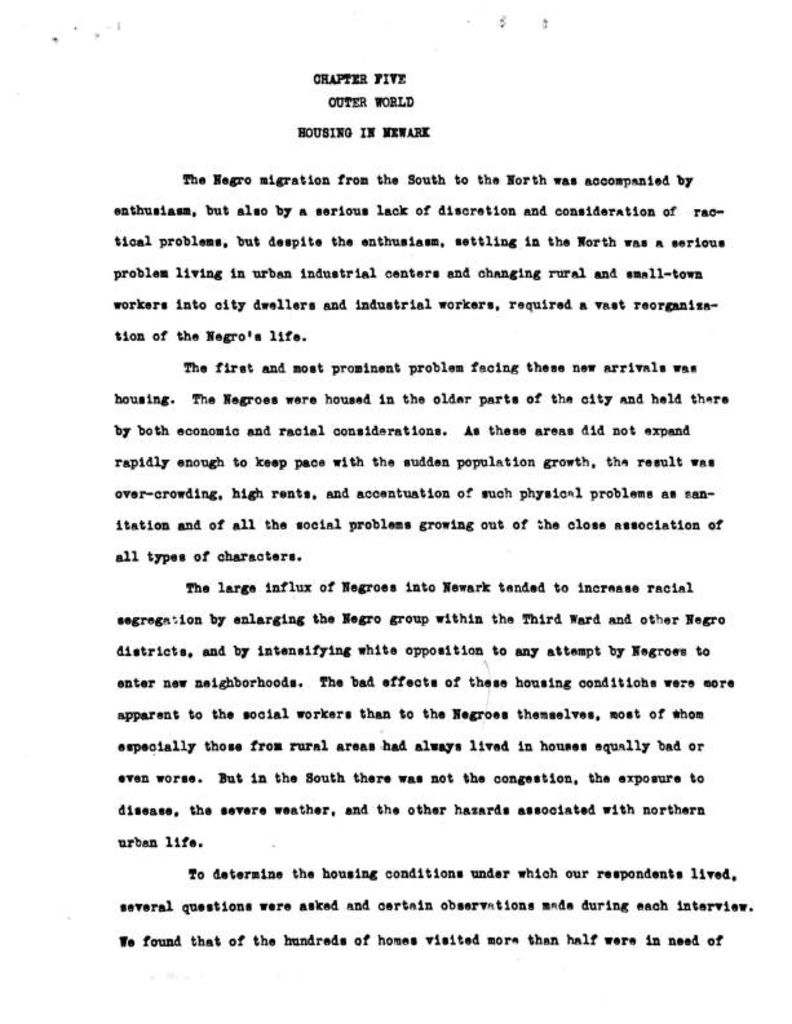

Report by Works Progress Administration staff writers in the 1930s describing the living conditions of Newark’s African American communities in the city’s Third Ward. — Credit: NJ State Archives

Population chart of African American residents of Newark by ward from 1890-1930. The chart shows a marked population increase for African Americans in the Third Ward between these years. — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

A look inside the apartment of an African American family at 22 Clayton Street in Newark. — Credit: WPA Photographs, NJ State Archives

A look inside the apartment of an African American family at 22 Clayton Street in Newark. — Credit: WPA Photographs, NJ State Archives

Report by Works Progress Administration staff writers in the 1930s describing the housing conditions faced by Newark’s African American communities . — Credit: NJ State Archives

Photograph from the PSEG archives of an African American repairman at work. — Credit: PSEG

Photograph from the PSEG archives of an African American stoker at work. — Credit: PSEG

Article from the Newark Evening News in 1936 covering a demonstration attended by 5,000 followers of Father Divine in Newark. — Credit: Newark Public Library

A look inside the office of the Urban League at 58 West Market Street in Newark, which was purchased in 1918. The Urban League was one of the most active and influential organizations advocating for African Americans in Newark in the early 1900s. — Credit: WPA Photographs, NJ State Archives

A detailed chronology of the activities of the Essex County Urban League from 1917-1952. The Urban League was one of the most active and influential organizations advocating for African Americans in Newark in the early 1900s. — Credit: Newark Public Library

A look inside an African American newspaper office in Newark in the early 1930s. The newspaper was most likely the New Jersey Herald News (later the Newark Herald News). — Credit: WPA Photographs, NJ State Archives

Poem written by William Maxwell, an influential political figure in Newark in the early 1900s. Maxwell was the first African American editor of the Newark Ledger and active in numerous political organizations in the city. — Credit: NJ Historical Society

Poster to advertise a mass meeting of the “New Idea” Colored Republican League” of the Ninth Ward. This was just one of many African American political organizations in Newark in the early 1900s. — Credit: NJ Historical Society