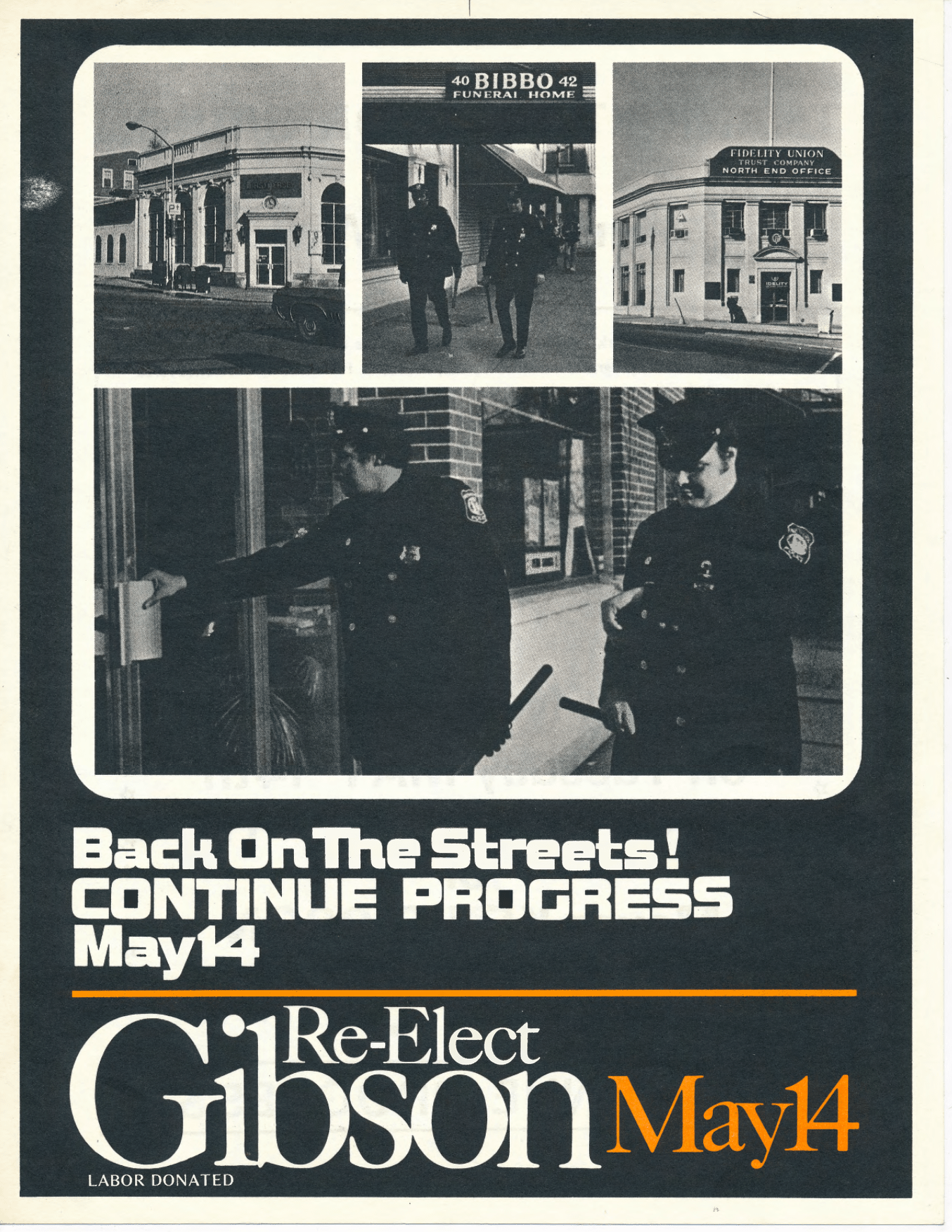

Struggles for Police Reform

With the election of Ken Gibson as Newark’s first black mayor in 1970, many in the city’s black and Puerto Rican communities saw the possibility for reform in City Hall—particularly regarding the practices of the police department. The 1967 rebellion three years earlier had cast the national spotlight on the corruption within the department, as well as the NPD’s oppressive and inhumane treatment of Black and Puerto Rican citizens. One of Gibson’s first moves as mayor was to appoint John Redden, a white veteran officer known for his stance against police corruption, to the position of Police Director to clean up the department. Though opposed by many Black residents and Central Ward City Councilman Dennis Westbrooks, who demanded a Black police director, the appointment of Redden demonstrated Gibson’s priorities for police reform but also an effort to appease the city’s white policemen and citizens.

Redden’s priorities as police director included increasing police protection for the downtown business district, rooting out corrupt officers, and improving management. Under his direction, the Housing Authority Police Force was incorporated into the Newark Police Department in 1972, thereby expanding the number of Black and Latino members of the force. Although Redden spoke of his goals of recruiting more Black officers, however, the department fell short in its efforts, claiming that young Black men did not want to be “a tool of the white oppressors.” Though by 1970 Newark’s population was 54% Black and 12% Latino, by 1975 only 24% of officers in the Newark Police Department were Black, while a mere 2% were Latino.

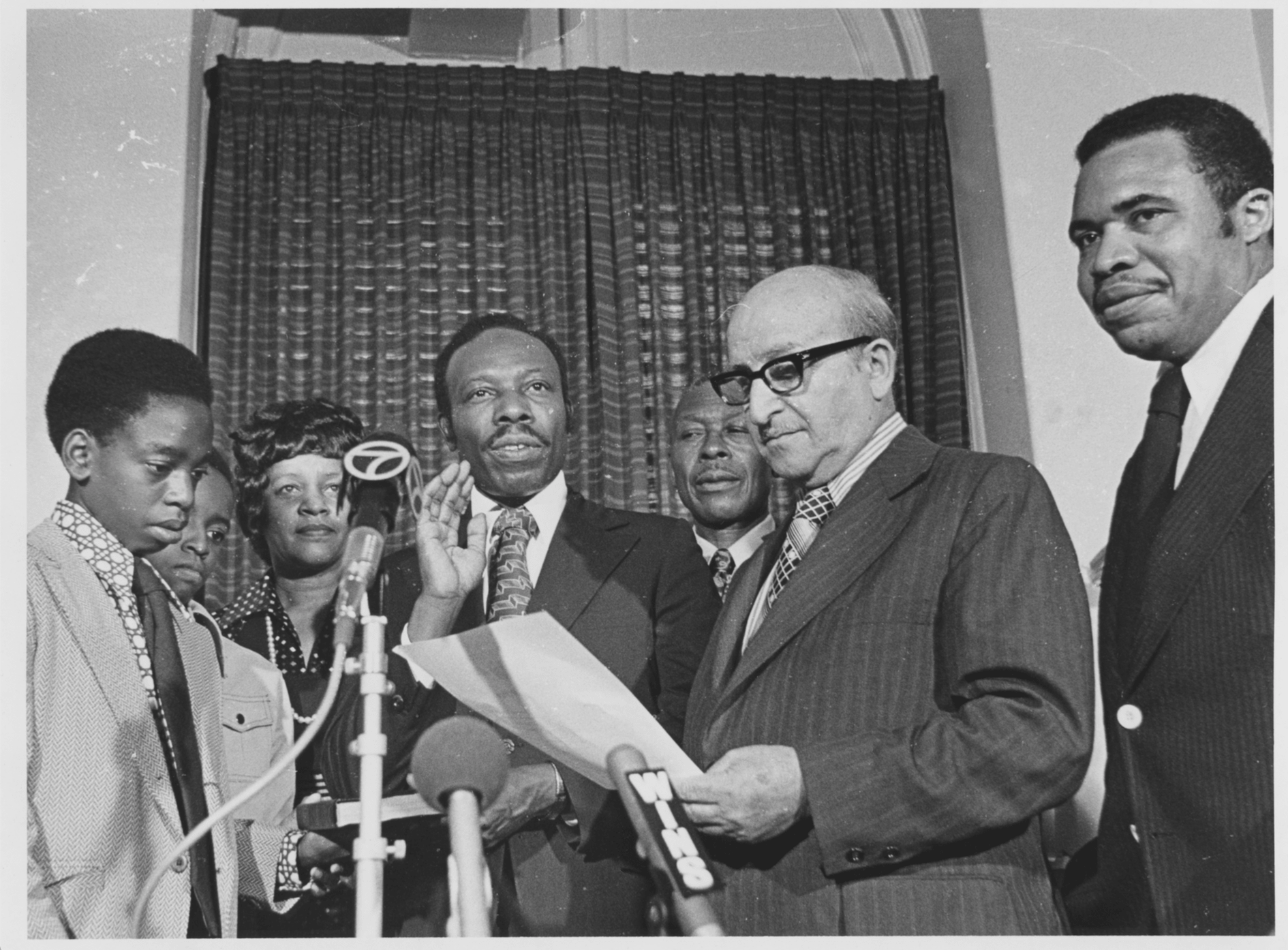

In December 1973, in the midst of the controversy over Amiri Baraka’s Kawaida Towers housing project in the North Ward, Redden resigned as police director in protest over the role police were asked to play in protecting the construction work. White officers had openly sided with white citizens in the North Ward to physically block Black laborers from the construction site. In other words, rather than protect Black construction workers from violent white mobs and white cops, as ordered by City Hall, Redden chose to resign. To fill his position, Mayor Gibson nominated Edward Kerr, a 15-year veteran of the department, and its highest ranking Black officer. Although the City Council, which consisted of six white and three Black councilmen, rejected his appointment four times, Kerr was finally approved in July 1973, making him the first Black police director in Newark’s history. Kerr’s time as police director was short-lived, however, as he was replaced by Lt. Hubert Williams in June 1974.

Although Newark had Black representation at the highest level in the police department, these directors struggled to change the functions and culture of policing in the city with a predominantly white police force. During Gibson’s administration, there were numerous cases of alleged police brutality that attracted widespread attention and public outcry. Amiri Baraka complained of frequent police violence and intimidation directed toward his organization in Newark, including several instances of gunfire into buildings. In August 1973, members of the police department’s Tactical Force beat Ramon Rivera, Director of OYE, Inc., after he advocated for a child who had been injured in an abandoned building.

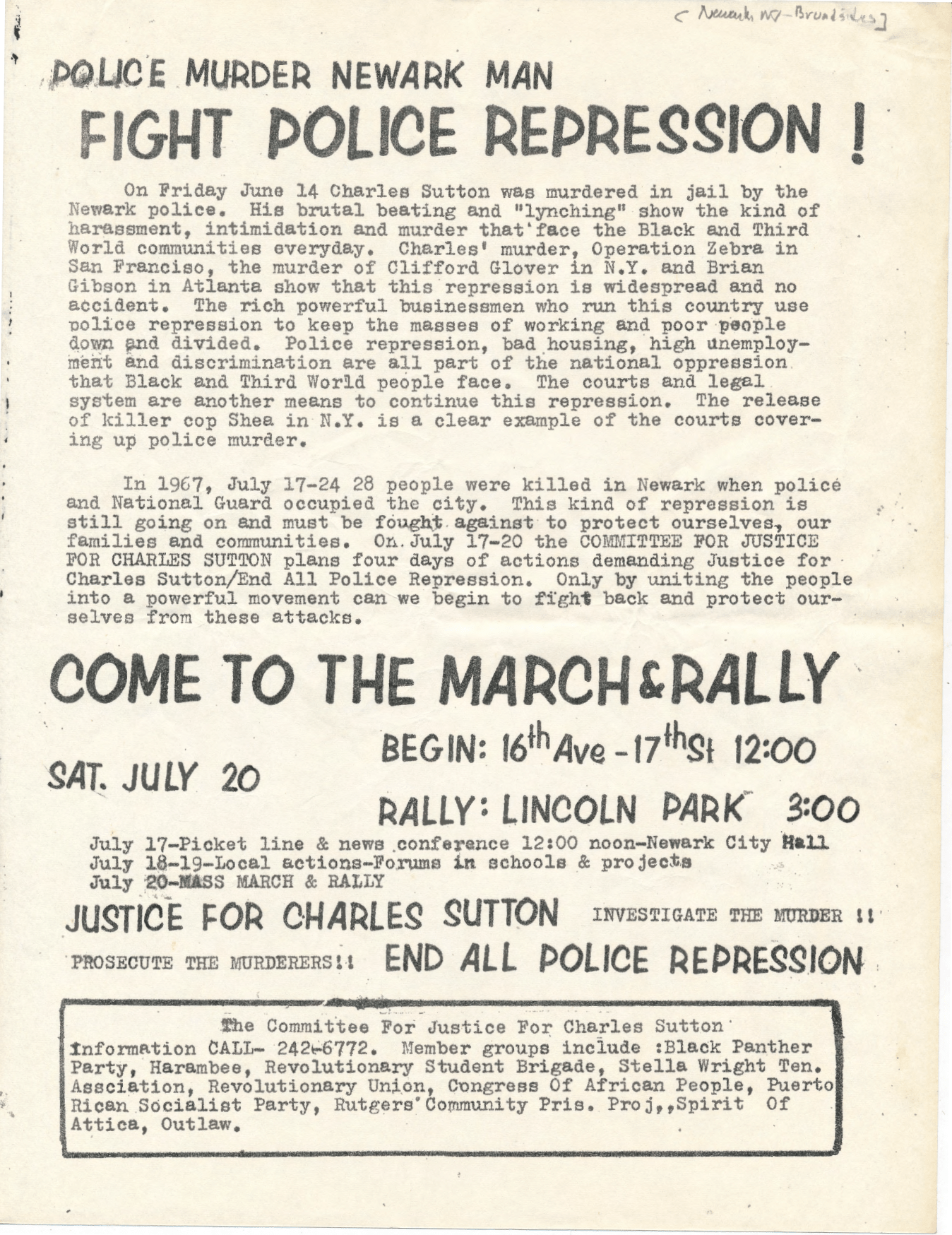

In June 1974, Charles Sutton, a 28-year-old Black man, was found dead in a Newark jail cell. Sutton had been arrested on a parole violation on June 12th, but when he was scheduled to appear in court two days later, his family was informed that he had hanged himself in his cell. Family and friends challenged the claims of Newark Police and the County Medical Examiner’s Office that Sutton was depressed and took his own life, and the ACLU argued that Sutton had suffered injuries that were not explained in the Medical Examiner’s report. Community organizers rallied around the case, linking Sutton’s death to the long history of racist police violence in the city. The Committee For Justice For Charles Sutton, led a series of demonstrations from July 17-20th, including a march to protest “the kind of harassment, intimidation and murder that face the Black and Third World communities everyday.” The protests also marked the seventh anniversary of the 1967 Newark Rebellion, and the Committee argued that the rampant police violence and repression during the rebellion was an ongoing problem that “must be fought to protect ourselves, our families and communities.” Member groups of the Committee included The Black Panther Party, the Congress of African People (CAP), the Stella Wright Tenants Association, the Puerto Rican Socialist Party, and other organizations.

The police violence and repression that the Committee For Justice For Charles Sutton protested gained national attention just months later, when police actions sparked the 1974 Puerto Rican Rebellion. On September 1st, as some 6,000 Puerto Ricans gathered in Branch Brook Park for a day of picnics, games, and leisure, Essex County police officers on horseback aggressively broke up a dice game and were met by jeers and flying cans by some nearby kids. The confrontation escalated quickly, as mounted police rode through the crowd, injuring several people including a 4-year-old child. As crowds swelled, police armed with nightsticks and shotguns stared down an angry crowd armed with rocks and sticks. Although Anthony Imperiale, the infamous white vigilante and State Senator from the North Ward urged police to clear the park, which would have almost certainly led to massive bloodshed, Mayor Gibson managed to de-escalate the situation by leading a delegation to City Hall to discuss plans for dealing with the situation. The next day, however, as angry demonstrators returned to City Hall, police surrounded the crowd and attacked when protestors threw rocks and bottles at the building. In the ensuing confrontations that lasted throughout the night, police swung their clubs “at anyone within striking distance,” leaving dozens injured and two dead.

As police abuses against black and Puerto Rican communities went virtually unchecked in the 1970s, several organizations fought to protect their communities and reform police practices. The day after the Puerto Rican Rebellion, Sigfredo Carrion of the Puerto Rican Socialist Party helped organized the People’s Committee Against Police Brutality and Repression (PCAPBR) to address the demands of Newark’s Black and Puerto Rican communities for police reform. These seven demands included the formation of a Community Police Review Board, the firing of Hubert Williams, the elimination of the Tactical Squad and Mounted Police, and that city and state police stay away from Puerto Rican community activities. Within three days, PCAPBR reportedly collected 10,000 signatures to put the police review board on the next election ballot.

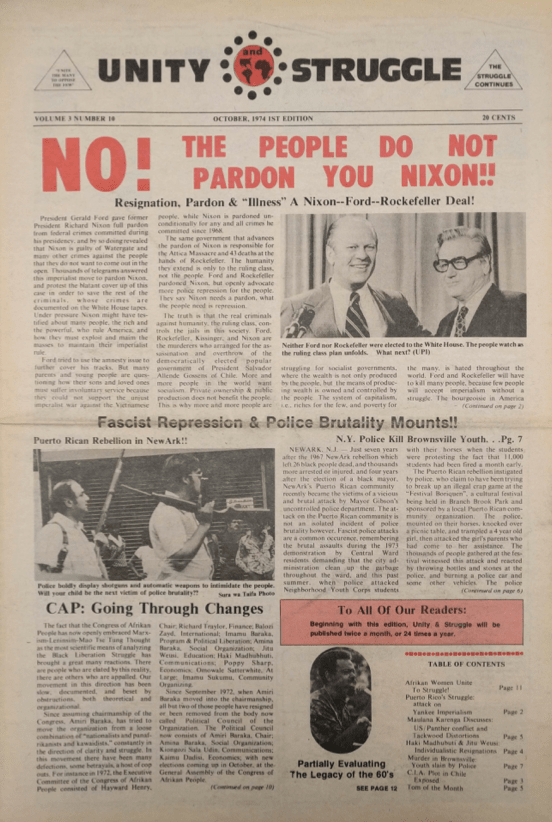

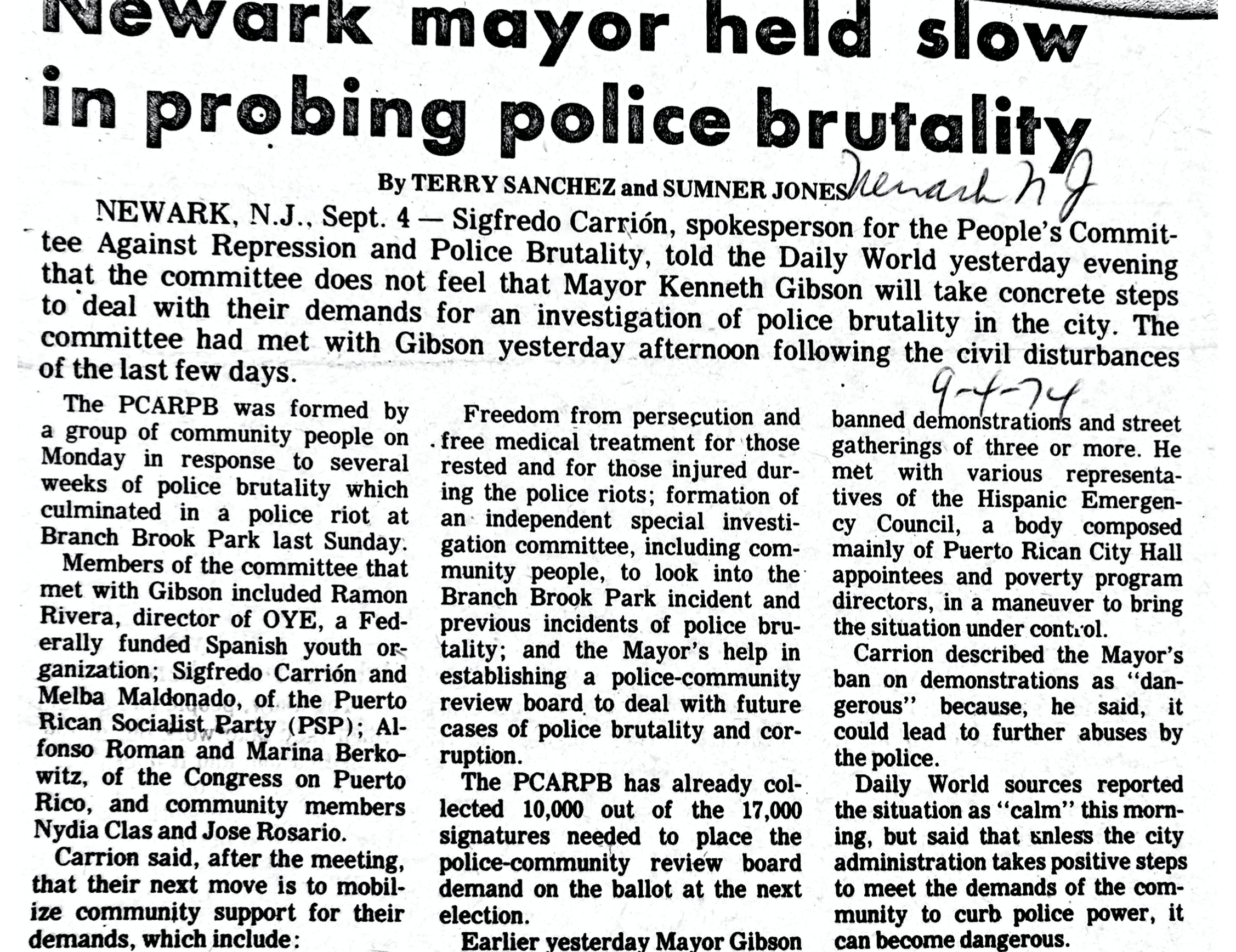

In October 1974, the Congress of African People (CAP) launched a national “Stop Killer Cops” campaign to expose the role of police violence in government oppression of poor Black and Latino communities. To combat police brutality, CAP held local forums to organize communities around police reform, issued demands to city governments, and led mass demonstrations and marches in Newark and other cities. Some of the most common demands were: the firing of abusive officers, the creation of civilian review boards, and increased hiring of Black and Puerto Rican patrolmen. CAP carried news from the campaign in various cities in an effort to promote a nation-wide challenge to police brutality and oppression.

Despite continued organizing in Newark’s Black and Puerto Rican communities for police reform, these groups achieved little success in curbing the abusive practices of the Newark Police Department. While Black and Puerto Rican communities struggled for police reform both locally and nationally, the federal government was working feverishly throughout the 1970s and 1980s to strengthen local and federal law enforcement agencies under the banner of “law and order”—which would have disastrous consequences for Black and Brown communities.

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Dorothy Guyot, Coping With Crime in Newark

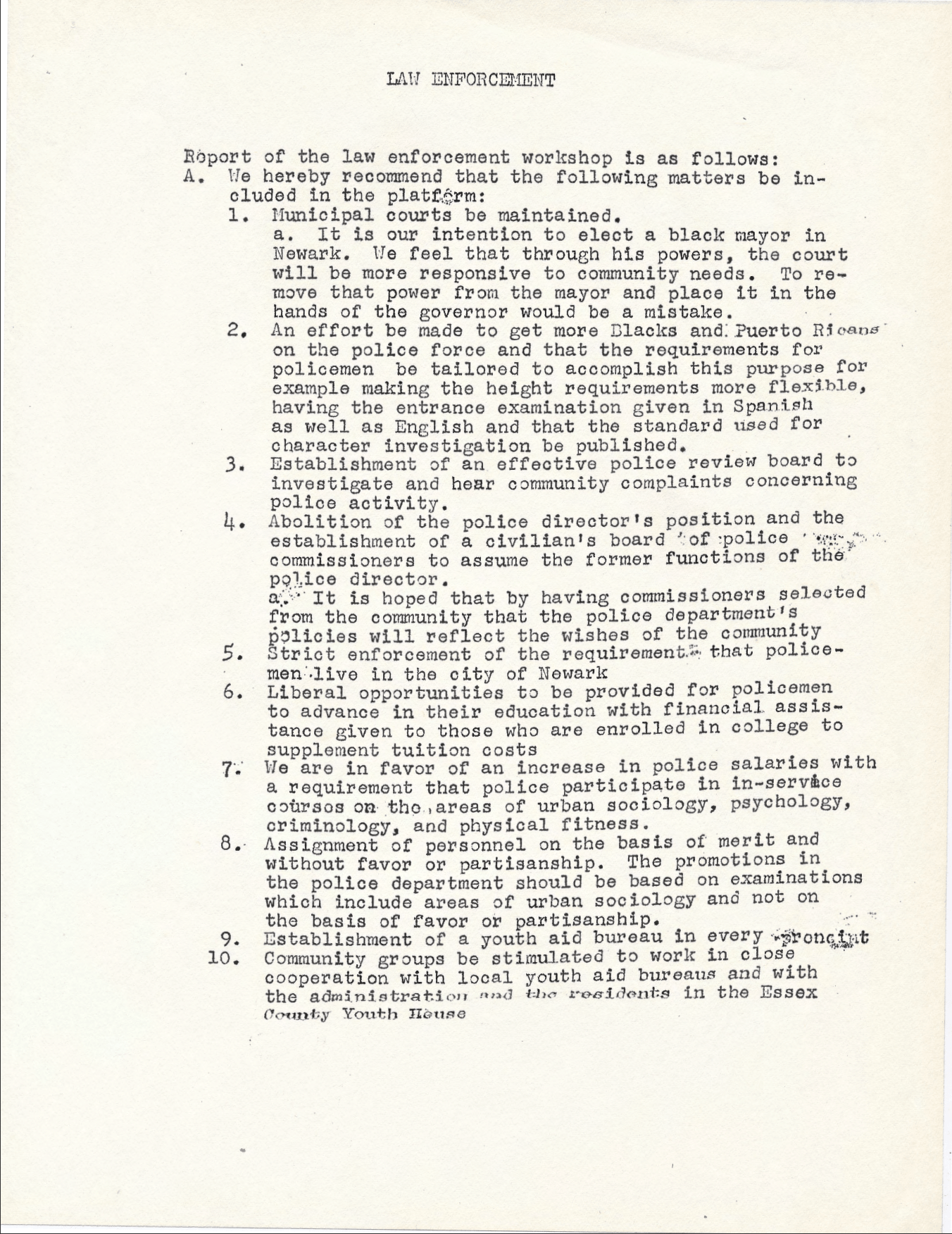

A report from the Law Enforcement Workshop of the 1969 Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention. The report includes 10 demands for police reform in Newark as part of the Convention Platform. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

In this clip from a 2009 oral history interview conducted by Bob Curvin, Ken Gibson discusses his relationship with the Newark Police Department and his decision to appoint John Redden during his first term. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

Edward Kerr is sworn in as Newark’s first African American Police Director in 1973 as Mayor Gibson (R) looks on. –Credit: Newark Public Library

A flyer for a march and rally on July 20, 1974 to demand justice for Charles Sutton, who died while in police custody. The flyer includes information on his death and its broader context. –Credit: Newark Public Library

October 1974 edition of Unity and Struggle, the national newspaper of the Congress of Afrikan People (CAP). This edition includes coverage of the 1974 Puerto Rican Rebellion. — Credit: NYU Tamiment Library

Explore The Archives

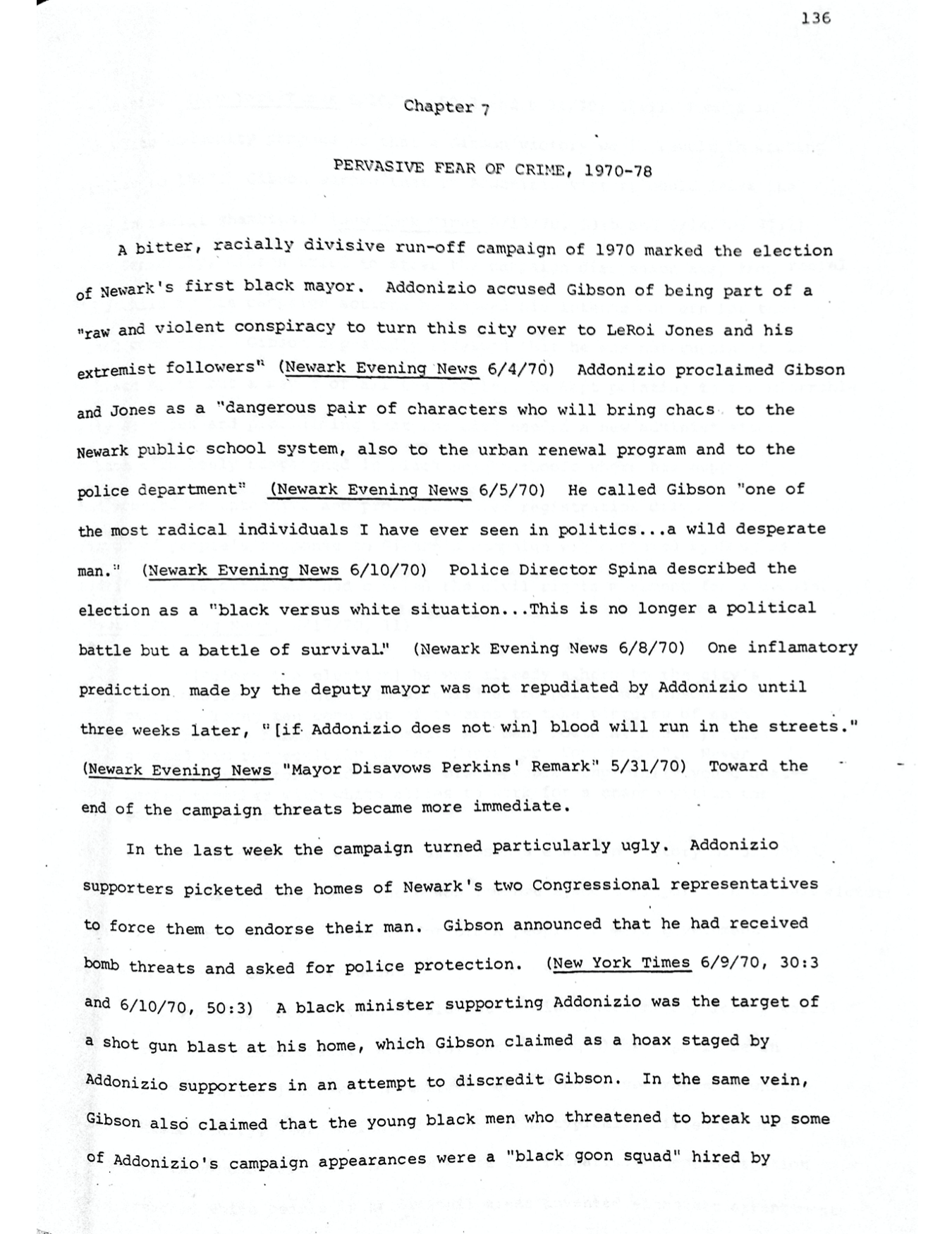

Excerpt from a 1980 report “Coping With Crime in Newark,” by Dorothy Guyot, for the Governmental Response to Crime Project, Northwestern University Center for Urban Studies. The excerpt covers the political history of the Newark Police Department during the Addonizio and Gibson administrations. –Credit: Newark Public Library

A mob of North Ward residents attempt to block the entrance of the Kawaida Towers construction site, while Oscar Mersier (center) and other Black laborers try to enter with a police escort on November 22, 1972. —Credit: Dwight J. Johnson/The Star-Ledger

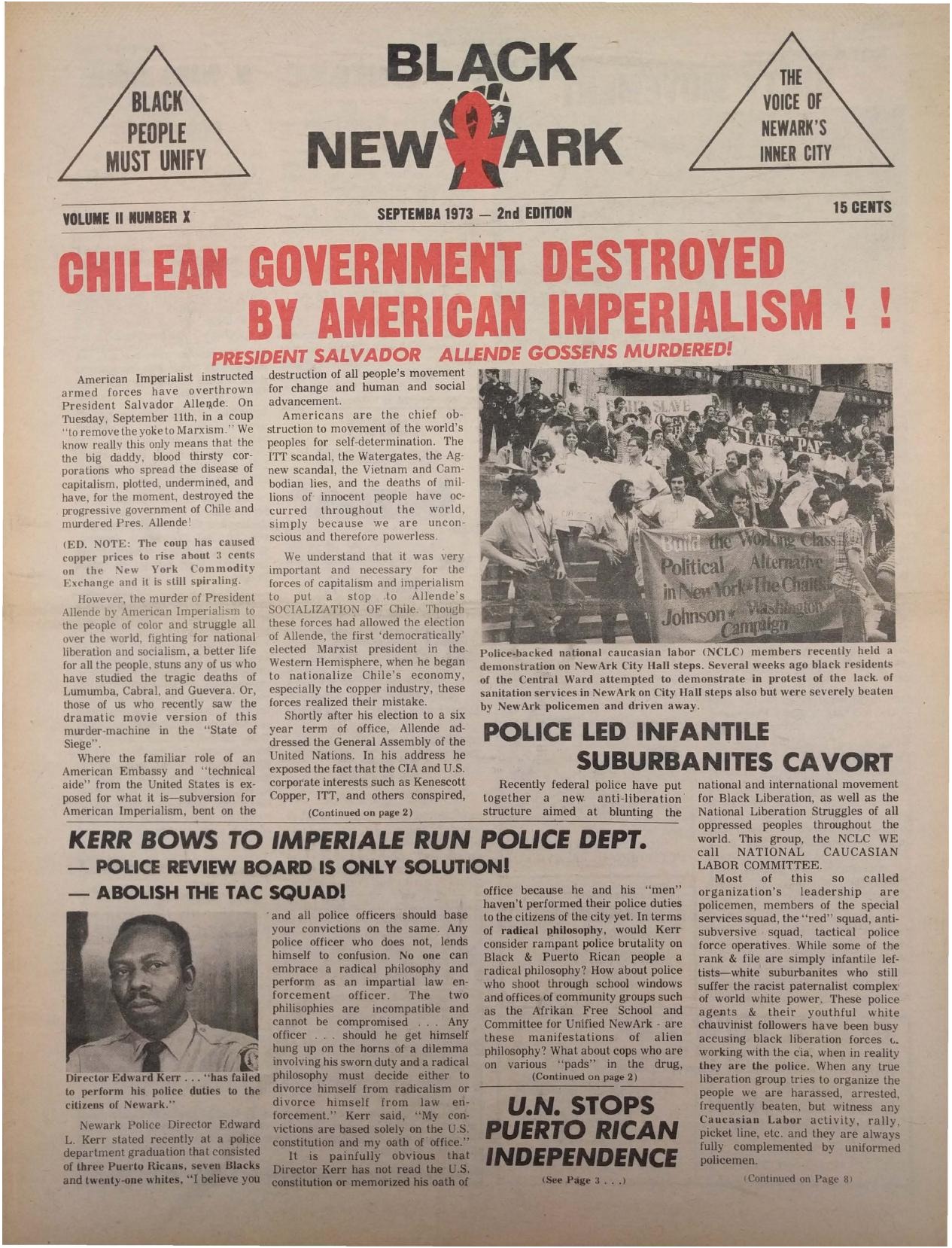

Sept. 1973 edition of Black NewArk, the local newspaper of the Committee For Unified Newark (CFUN). See pg. 8 for coverage of the police beating of Ramon Rivera. –Credit: NYU Tamiment Library

News article from Daily World on September 4, 1974, covering the Puerto Rican Rebellion in Newark and the People’s Committee Against Police Brutality and Repression (PCAPBR). –Credit: NYU Tamiment Library

Advertisement for the Congress of Afrikan People’s Stop Killer Cops campaign in 1974. This ad for community forums was found in an edition of CAP’s newspaper, Unity and Struggle. –Credit: NYU Tamiment Library

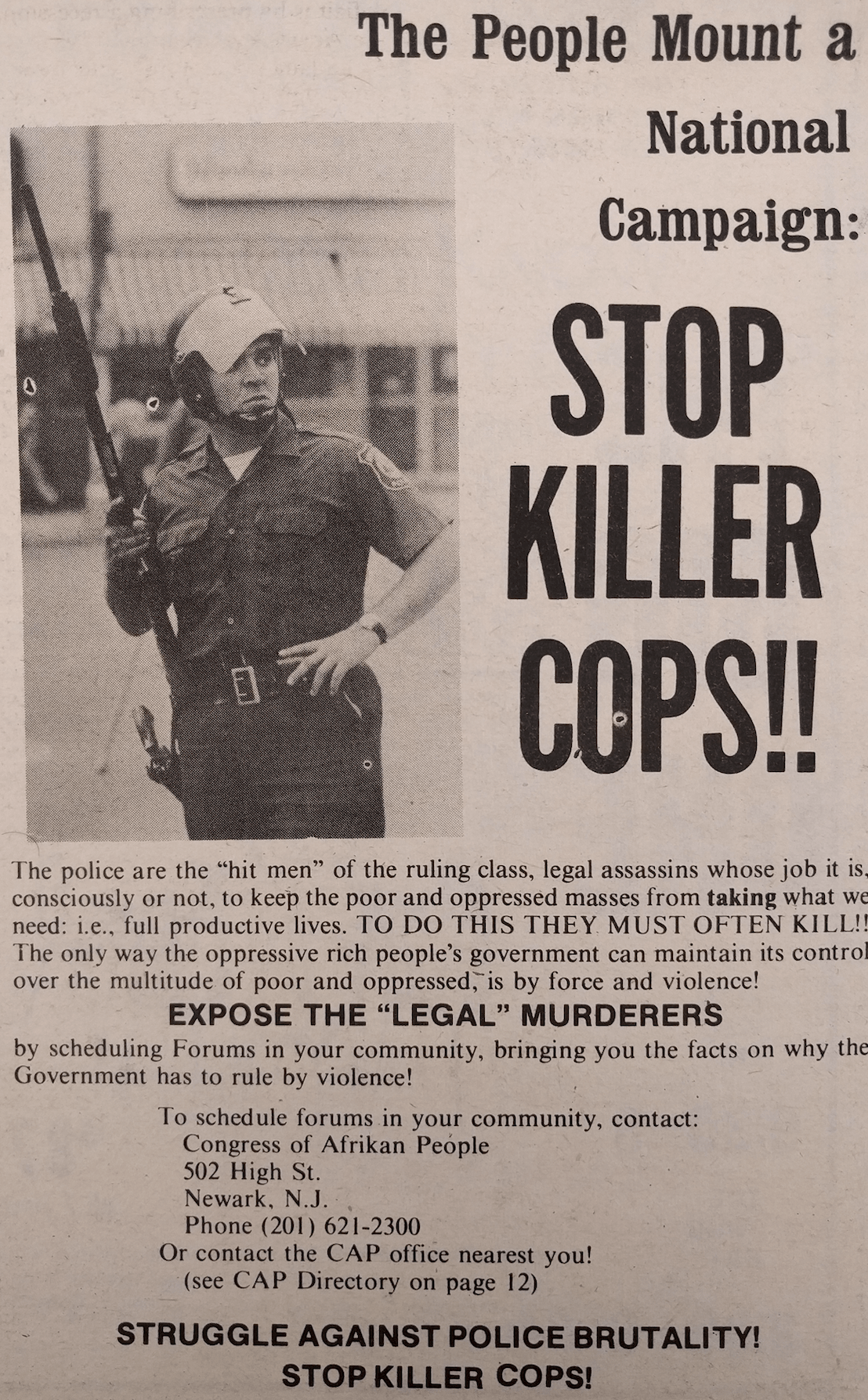

A campaign flyer for Mayor Gibson’s re-election campaign in 1974, focused on crime and policing in Newark during his first term. “Tough enforcement, fast justice, effective correction–that’s the Gibson way to fight crime!” the flyer reads. –Credit: Newark Public Library

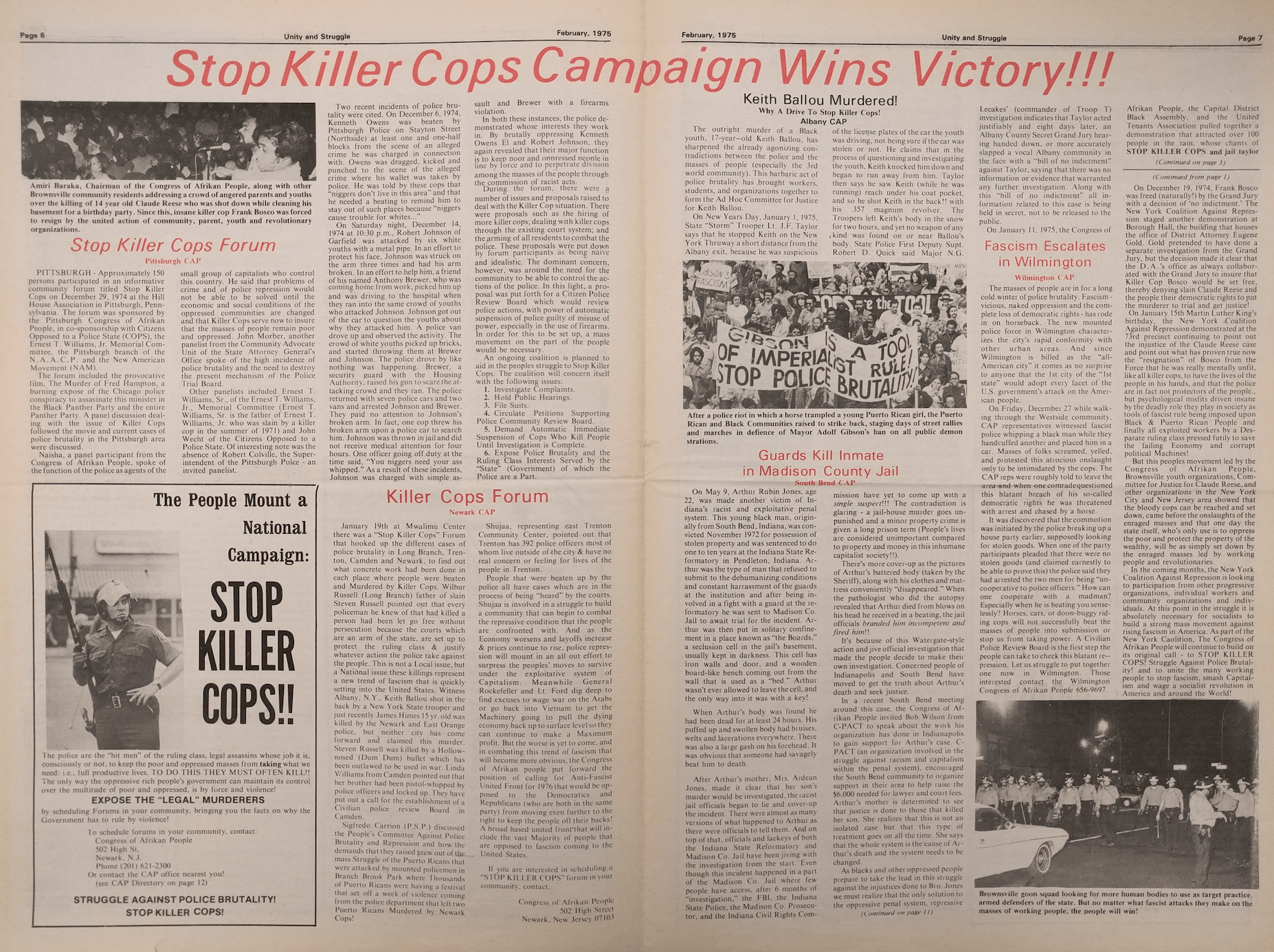

A report on the Congress of Afrikan People’s national Stop Killer Cops campaign from the February 1975 edition of CAP’s newspaper, Unity and Struggle. The report features coverage of a statewide forum held in Newark that January. –Credit: NYU Tamiment Library

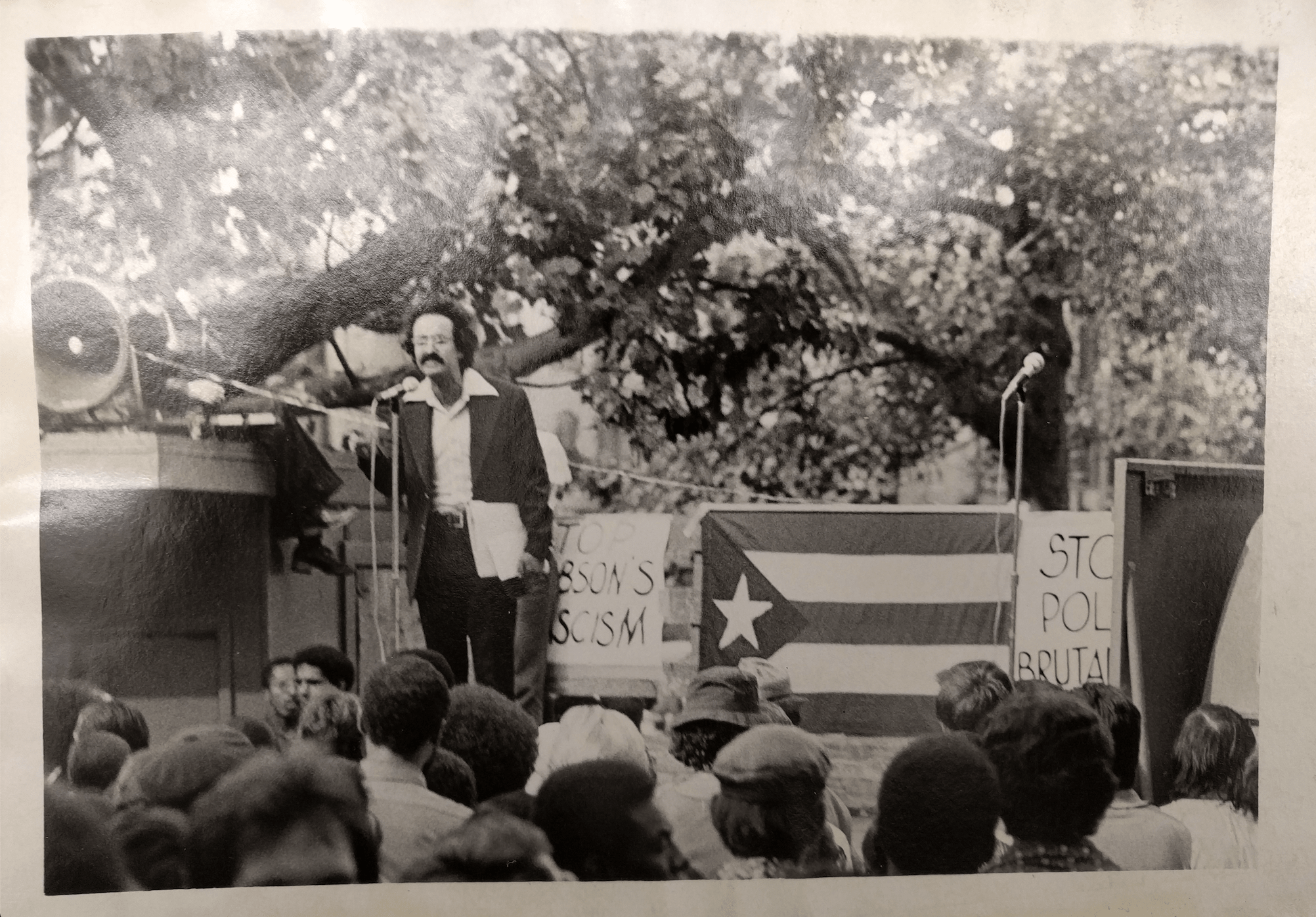

Sigfredo Carrion speaks at a rally in September 1974 protesting police brutality in Newark. The rally was organized by the Peoples Committee Against Police Brutality and Repression in the wake of the Puerto Rican Rebellion. –Credit: NYU Tamiment Library

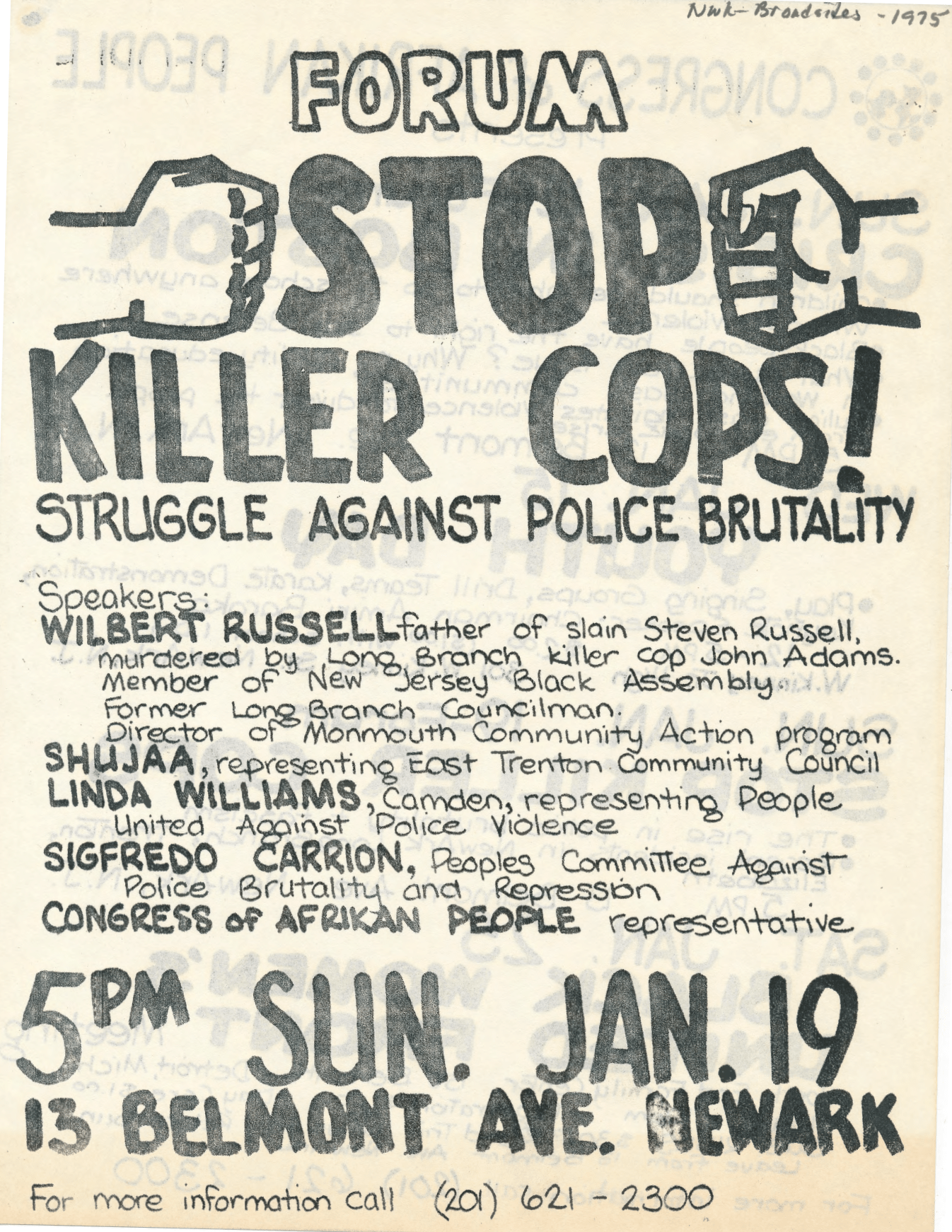

Flyer for a 1975 forum on the Congress of Afrikan People’s “Stop Killer Cops” program, which organized Black and Puerto Rican people to resist police brutality. The Congress of Afrikan People was founded in 1970 as a Pan-African, nationalist organization that promoted black political empowerment, with its headquarters in Newark, NJ. — Credit: Newark Public Library