Job Training and Black Employment

Section 1: Government Training Programs

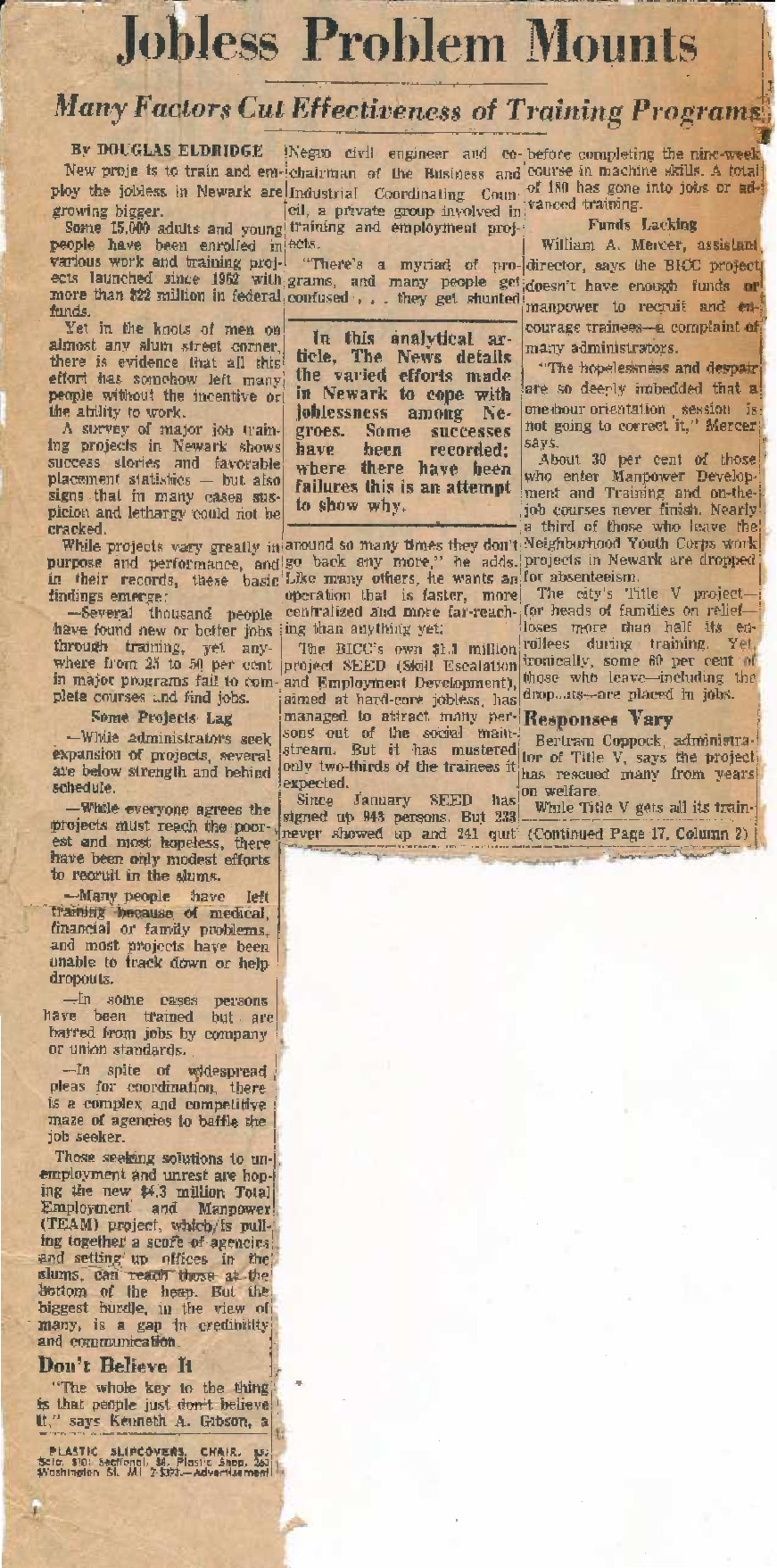

In 1968, P. Bernard Nortman, Chief of the Newark Office of Economic Development under then-Mayor Hugh J. Addonizio, noted that with the “exodus of affluent and middle classes in Newark there came an increasing flow of unskilled and poorly educated non-whites from the south into the city.” Subsidized by the federal government through discriminatory home loan programs and highway construction through Black neighborhoods, this white flight to the suburbs began in the 1950s and drained population, tax revenues, and jobs from cities across the country. In addition, many workers dependent on jobs in the manufacturing industry were displaced due to the changes of automation and technology occurring in the U.S. economy. However, as a result of the Manpower Development and Training Act of 1962, manpower programs nationwide received nearly $50 million in financing by 1968 to address this problem. In particular, Newark’s Total Employment and Manpower (TEAM) neighborhood employment organization was operating under a $4.4 million federal grant and had processed 6,000 people to provide a variety of services, including manpower training. Such aid was considered “keep them cool” money by the US Department of Labor in order to prevent “riots” in cities like Newark, which were considered to be “sensitive and high in racial tension.”

Despite these efforts, Newark was declared a “persistent unemployment area” by the federal government in 1971. This was no surprise to the new Gibson administration, since Nortman predicted in 1968 that 16,000 additional residents would be entering the workforce by 1975, in addition to the current unemployed and underemployed residents already in the city. He also noted that half the number of jobs needed to serve this growing labor force would be needed in the city, itself, and almost 25,000 additional jobs would need to be created outside of Newark to fill the expected job gap. Of his many recommendations to address this problem, Nortman highlighted the need for more training in business services; training for the expected jobs through the new Medical School; closer relationships between manpower authorities and the NY Port Authority; and more emphasis on preparing people for positions in government and non-profit sectors, identified as the “fastest growing sector in Newark.”

To this end, TEAM’s Executive Director, Arthur S. Jones, noted in 1968 that in the first four months of operation, TEAM had placed “546 people in the private sector and 26 in the public sector of businesses.” By 1970, Jones reported that $2 million had been paid in wages and stipends to persons in training; and $400,000 was earned by persons who had found jobs through the program. Harry Wheeler, Director of Newark’s Manpower Training Office in 1971, stated that since its inception [TEAM] had trained 4,115 workers and placed 3,887 in jobs, which included clerical and machine shop positions.

Annual Reports submitted by Mayor Gibson during the years of 1971-1973 reported that a total of 21,192 jobs had been provided under his administration. However, according to scholar Willa Johnson, “… there [was] a huge force involved in training which [was also] being counted as employed.” She further claimed that job training under Mayor Gibson continued to focus on clerical, machinery, and other entry-level skills. Johnson asserts that, based on the calculation method preferred by the N.J. Department of Labor & Industry, Newark’s total unemployment during that same period was reduced by less than 250 people, despite the 24,000 jobs reportedly created. By his own account in the Mayor’s Third Annual Report, Gibson reported that over 5,000 people were placed in “meaningful jobs,” yet over 20,000 people participated in pre-vocational orientation, on-the-job training, and training for entry level skills. Nortman cautioned against this type of training when he noted that “many manpower programs in Newark are repetitive and overlapping. Several train people in the same type of skill, often utilizing a slightly different label or job-title…duplication and lack of specific goals inherent in some of these programs siphon off much well-intentioned effort and good will.”

Based on the information noted above, there seems to have been no assessment of the type and availability of jobs accessible to Newark residents when Mayor Gibson took office. To be fair, every new mayor has to “hit the ground running” with what they have to work with in terms of available staff and funding, and perhaps this assessment task wasn’t possible at the time Mayor Gibson took office. Nonetheless, Newark was bustling with new employment opportunities at sites like the Airport and the Medical School during Gibson’s first term. Nortman had noted that despite the increase in educational and skill requirements for these new jobs “the manpower training programs continue[d] to prepare trainees for less promising work…training resources [were] being used on many jobs which [were] primarily low-skilled…without due regard or the possibility that the jobs [would] not be available in the future or that the [existing] jobs [did] not offer chances for advancement.”

Nortman had laid out a number of recommendations for the Addonizio administration in 1968, such as “identifying prospective vacancies in various departments and setting an explicit policy” to have these vacancies filled by residents who completed the appropriate training programs. Unfortunately, as if history was destined to repeat itself during the Gibson administration, federal and state training money came from agencies that did not seem to take note of Nortman’s observations. As a result, the Mayor’s efforts during his first term seemed to have little impact on the city’s unemployment problems.

In addition, when the federal government designated Newark as a “persistent unemployment area” in 1971, the city was entitled to increased federal and state aid totaling over $4 million. That same year, however, the state legislature created a Task Force on Urban Programs to oversee how Newark was spending these funds. This Task Force charged Gibson’s administration with inefficiency, wasteful duplication and bad planning. Although the Task Force acknowledged that the city needed “massive” aid, they warned it wouldn’t be given until reasonable assurances were given that the aid would be spent in an efficient manner. Later in 1974, despite boasting in his Second Annual Report that the city’s Manpower programs increased from $18.5 million to $30 million, the U.S. Department of Labor began extensive investigations into widespread abuses in Newark. Allegations of abuse were considered “far worse in Newark than elsewhere” and the Department was considering a recommendation to cut off manpower training money.

In retrospect, there might have been little else Mayor Gibson could do but to accept the opportunities that were presented through the state and federal programs to create opportunities that were already familiar to the city. However, history has revealed that the lack of foresight from federal and state agencies limited the impact that the new administration would have on the new economy and eventually on black employment and job training in the city, as a whole.

References:

Willa C. Johnson, “Illusions of Power: Gibson’s Impact Upon Employment Conditions in Newark, 1970-1974,” PhD Diss., Rutgers University, 1978.

Bernard Nortman, “An Economic Blueprint for Newark,” Office of Economic Development, City of Newark, July 1968.

“U.S. approves TEAM extension through July 31,” Star Ledger, March 20, 1968

“4.5% Cut for Jobs – TEAM gets $3.85 million for 1971,” Star Ledger, November 3, 1970

“Newark qualifies for added job aid,” Star Ledger, July 11, 1971

“State Panel Says Newark is Being Run Inefficiently,” New York Times, November 13, 1971

“Possible Abuses in Job Training Scrutinized in Newark and Gary,” New York Times, December 10, 1974

City of Newark Second Annual Report, 1972.

Third Annual Report – Mayor Kenneth A. Gibson reports to the Citizens of Newark, 1973.

DeOtis Taylor, organizer of the Blazer Work Training Program, discusses employment discrimination faced by Black men in Newark during the 1960s. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

A 1967 report conducted by researchers from Rutgers University on the population and labor force of Newark, NJ. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

January 1968 edition of the United Community Corporation’s newspaper, The Crusader, featuring coverage of the Total Employment and Manpower Project in Newark. –Credit: Newark Public Library

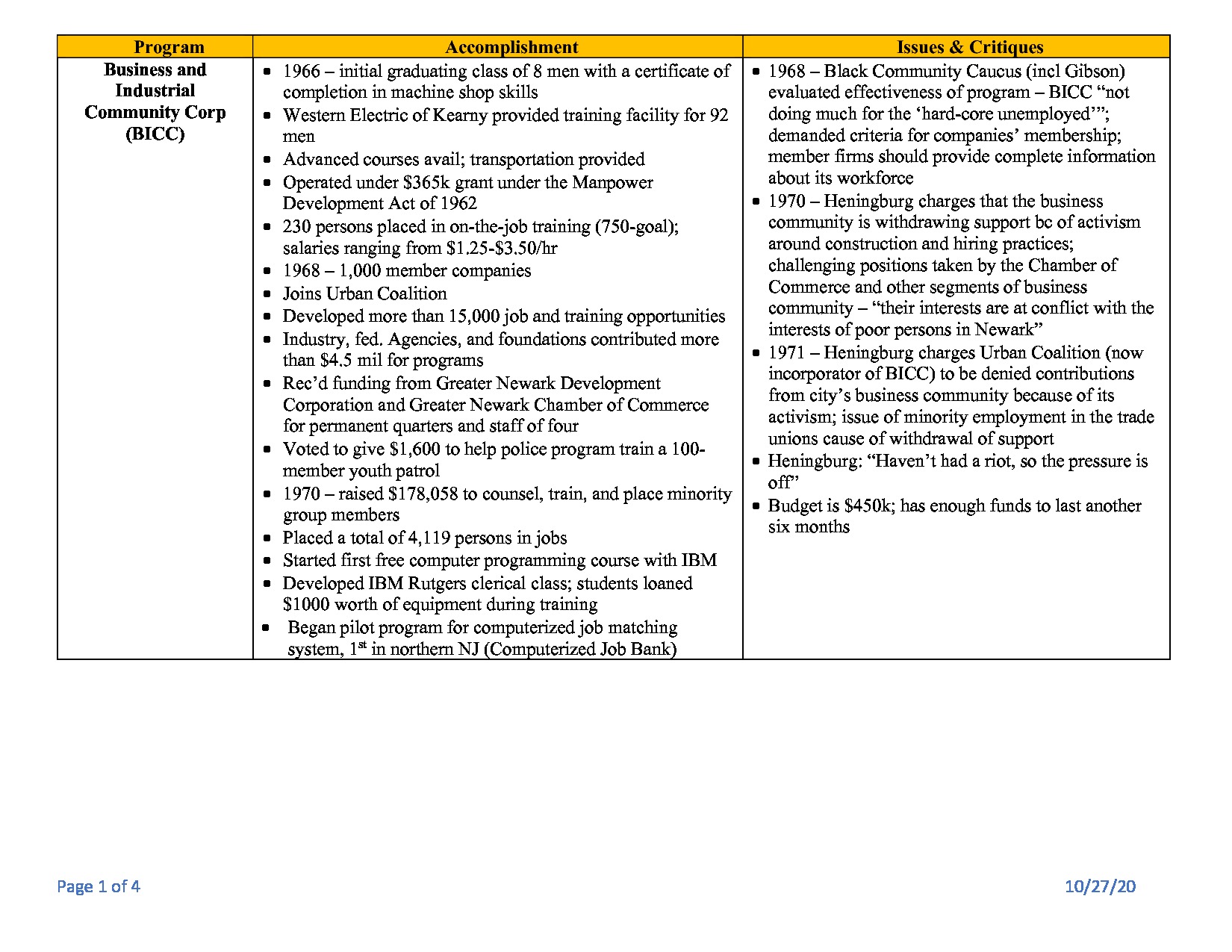

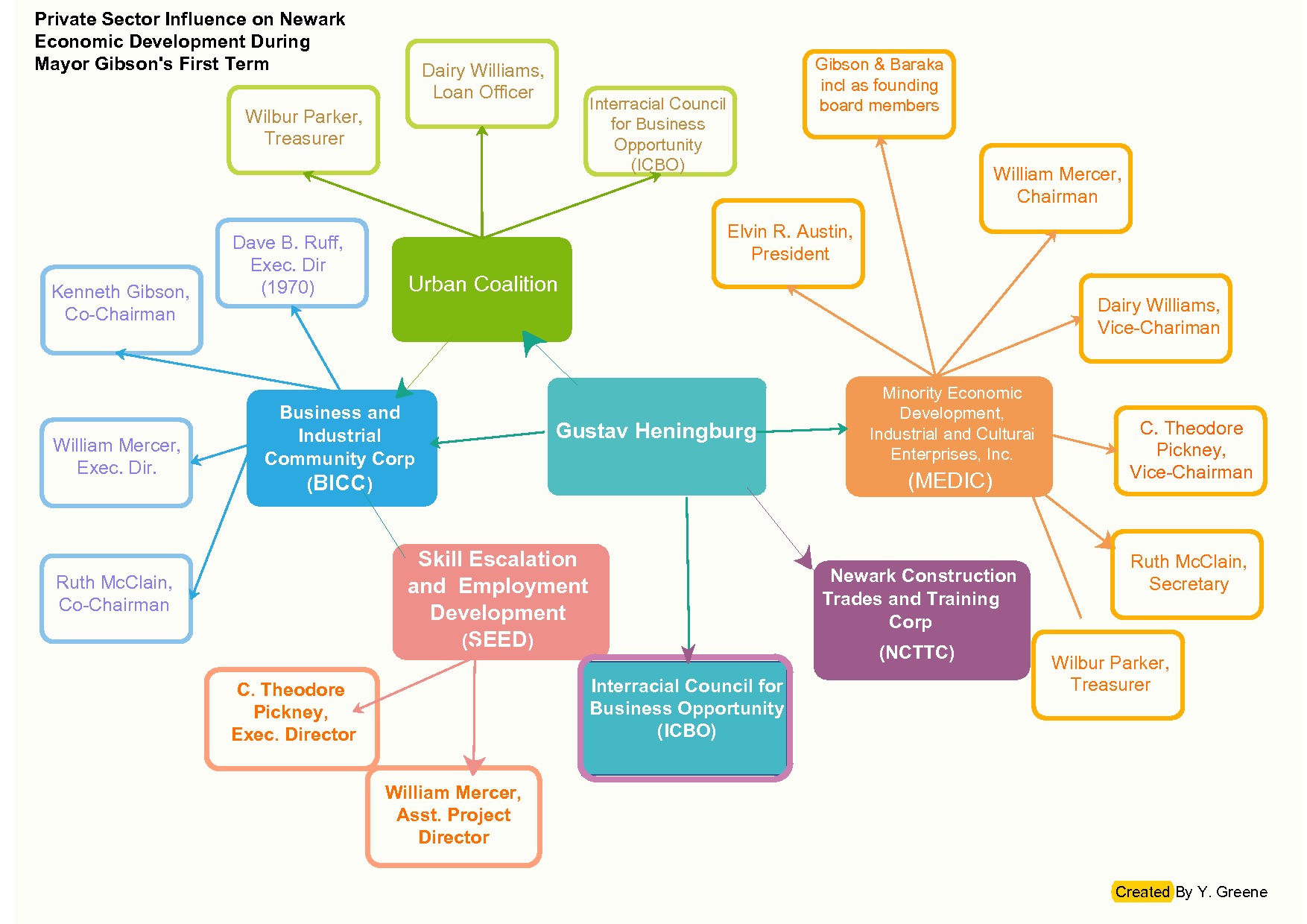

A chart highlighting the successes and shortcomings of various programs to support job training and economic development in Newark. –Credit: Yolanda Greene

Volume 1, Issue 2 of MEDIC’s newsletter, MEDIC News, published in 1971. This edition features coverage of a two-day Workshop Conference on Manpower in 1971, co-chaired by Ken Gibson and Harry Wheeler. –Credit: Newark Public Library

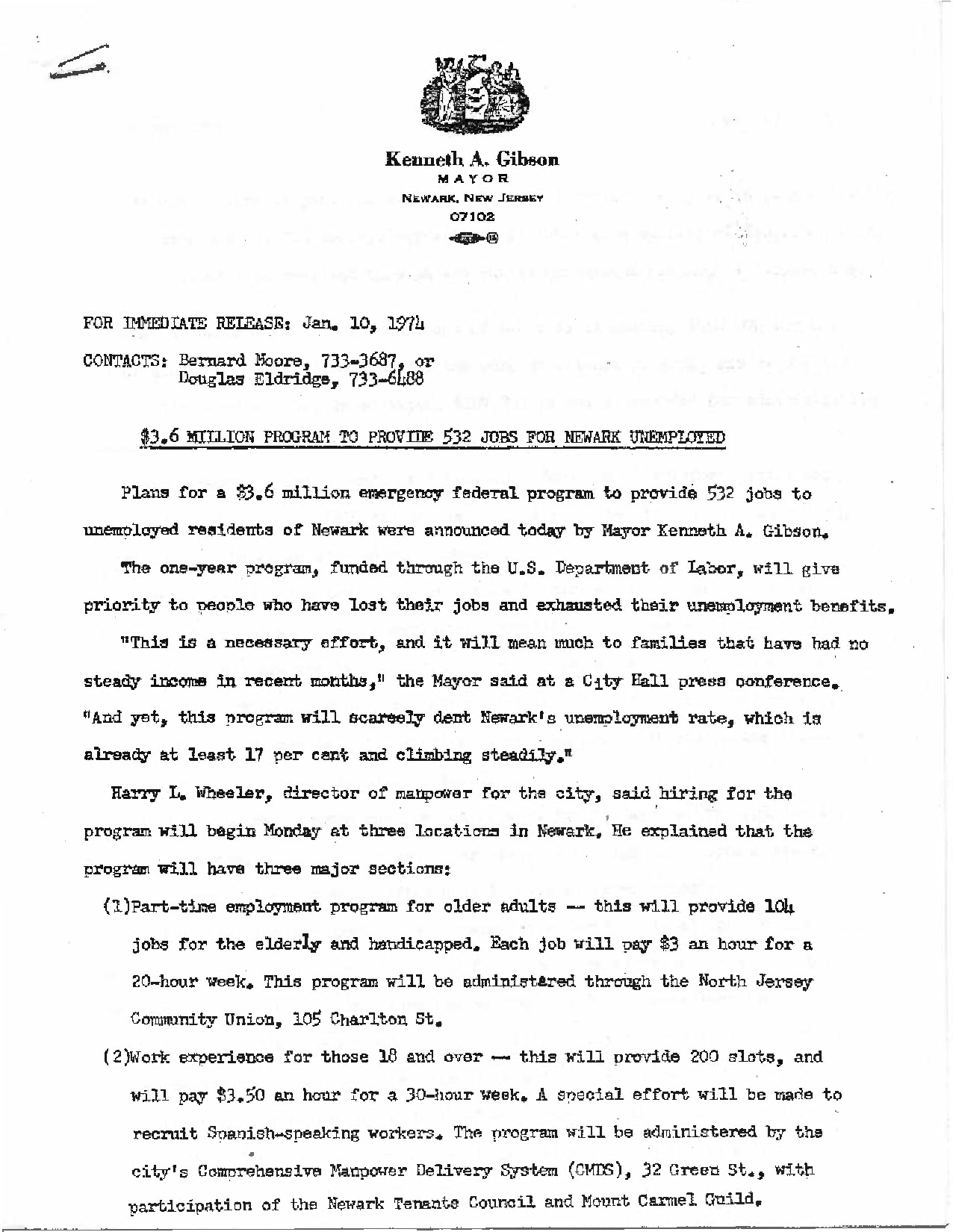

A press release from Mayor Gibson announcing an emergency federal program to provide jobs to 532 unemployed Newark residents, January 10, 1974. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Explore The Archives

A 1967 Newark Evening News article by Doug Eldridge analyzing the effectiveness of job training programs in Newark. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Gus Heningburg discusses the struggle to pass a New Jersey state law against employment discrimination. The law was introduced in 1974 during the fight for affirmative action in the construction industry in Newark and eventually passed the following year. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

Gus Heningburg describes the lessons learned from struggles to win equitable employment opportunities for Black and Puerto Ricans in the construction industry. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

Section 2: Local Training Programs

In 1965, representatives from businesses, civil rights organizations, government agencies, unions, social welfare agencies, and local people formed the Business Industrial Coordinating Council(BICC). The BICC was born out of the fight to integrate the Barringer High School construction project in 1963 and other resistance to racial discrimination in employment in the greater Newark area. This organization provided an opportunity for Black and Puerto Rican advocates to meet with business representatives during monthly round-table meetings to identify problems with employment discrimination and develop potential solutions. As a result, “counseling, training, and placement services for unemployed minorities” were developed which allowed the business community to be supplied with a “steady flow of qualified non-white workers.” In 1968, BICC was incorporated under the Greater Newark Urban Coalition and received funding from the Greater Newark Development Corporation and the Greater Newark Chamber of Commerce to take a “greater hand in the coordination of the manpower problem in Newark.” According to Newark’s Office of Economic Development, BICC member firms submitted open jobs to the Urban League, who then provided candidates to fill the jobs. By the end of 1968, 920 residents had been placed in jobs.

Kenneth Gibson, the outgoing co-chairman of BICC’s civil rights section, was a part of the Black Community Caucus which questioned the effectiveness of BICC. In the early part of 1968, the Caucus identified itself as “representation of the Negro Community which met during a six-week period to evaluate the effectiveness of BICC in ‘light of the intolerable high and disproportionate rate of unemployment in the non-white community.” Gibson argued that steps needed to be taken in order for BICC to become more effective. These steps included the establishment of criteria for the member firms of BICC and a public expulsion of any member firm that provided incomplete information or failed to meet the Corporation’s criteria. A month later, it seemed these measures were necessary, as three member firms were expelled from BICC for “refusing to submit data on non-white workers they employed.” Gibson later chose not to seek another term with BICC as he “expected to be involved in political activity and there [was] an unwritten law that BICC officers [did] not become involved politically.”

In addition to its main objectives, the BICC operated the Skill Escalation Employment and Development (SEED) daytime program. SEED was a federal program with $1.9 million in funding to operate two training programs for courses in machine shop and clerical skills and guaranteed a job to all who completed the course. However, Robert F. Lagged, Director of SEED, called for a study of the program’s large number of drop-outs, as he “reported less than 10% of the men referred for the project’s machine shop training finished the course.” Despite U.S. Rep. Peter W. Rodino’s contention in 1969 that “SEED was the only manpower training program in the nation that had reached the hardcore employed,” U.S. Asst. Sec. of Labor Arnold Weber stated that SEED was “an experimental program that had proved itself and should now be incorporated into a state training program.”

Determined to secure additional funding, BICC led a delegation of eight major Newark companies on a trip to Washington D.C. three months later. Their mission was to request $2.5 million to continue the SEED training program. Manpower administrator, Malcolm Lovell, of the U.S. Department of Labor, stated that funds for the SEED project were unavailable at the Department of Labor. He further directed that the “job training program must be revised and fit into one of the nationally designed programs.” C. Theodore Pinckney, Exec. Director of SEED, argued that revising the SEED format would weaken the program because, unlike other programs with screening measures that excluded many applicants, SEED accepted all of its applicants for job training and placement. Lovell, however, was resolute in his position that training development could be created with funds from existing national programs such as the Jobs Opportunities in the Business Sector (JOBS). Federal officials would eventually decide to support the city’s Manpower Training Skills Center instead of programs like SEED. Locally, funding from the Newark Model Cities for SEED was also tenuous, as leaders from these programs disagreed on the conditions under which funds were expected to be distributed. Eventually, according to BICC co-chair Ruth McClain, programs like SEED “softly and gently disappeared,” as city programs like TEAM dominated efforts to improve minority employment.

On the business side of Newark’s economic development in 1970, Newark was home to two of the state’s biggest department store chains, Bamberger’s and Hahne & Company, commonly known as Hahne’s. During Mayor Gibson’s first term, there was a 14% increase in retail sales. In addition, the central business sector, a 15-block stretch of area running down Broad Street between the Pennsylvania Railroad Station and Washington Street, was a bustling construction area within the city. Joining the existing skyline dotted by major institutions like Prudential Insurance Company and New Jersey Bell, came the construction of three significant hi-rise office complexes: the 26-story Gateway I office building and hotel complex; the 18-story Gateway II (home of Western Electric Company); and the 19-story Blue Cross/Blue Shield headquarters. These buildings would later be joined by the $300 million Meadowlands Complex and the $60 million, 27-story PSE&G headquarters. By the end of Gibson’s second term, over a billion dollars was spent on the construction of new office buildings, manufacturing facilities, retail establishments, warehouses, food processing plants, transportation and educational facilities. Further studies should be conducted to determine who got the lion’s share of the jobs, profits, and other economic benefits from all of this development.

References:

“BICC shows how to halt bias with profits,” Star Ledger, February 22, 1970

“Poverty agency getting funds for permanent office,” Star Ledger, January 20, 1968

“Job Assurances Asked – Negro demands Businessmen get,” Star Ledger, January 9, 1968

“BICC wants 3 firms expelled,” Star Ledger, February 6, 1968

“Business council re-elects leaders,” Star Ledger, January 8, 1969

“Rodino questions Schultz for a decision on SEED,” Star Ledger, September 4, 1969

“SEED told to revise format to get U.S. funds,” Star Ledger, December 7, 1969

“Two agencies disagree over job training funds,” Star Ledger, November 22, 1970

Nortman, P. Bernard, “An Economic Blueprint for Newark,” Office of Economic Development, City of Newark, July 1968

Greater Newark Chamber of Commerce, “The Newark Experience 1967-1977,” September 28, 1978

Note from the pamphlet: “This series of articles on the efforts of the Newark Business and Industrial Coordinating Committee to assist Negroes and Puerto Ricans in gaining employment was published by The Newark News in its issues of March 22-26, 1964. These pamphlets have been prepared by The News for distribution by the committee.” The BICC was established in the wake of the contentious protests at the Barringer High School construction sites in July 1963. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Ken Gibson discusses his involvement with the BICC in the 1960s. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

A booklet prepared by the BICC in 1967 offering an overview of the various job training programs available to Newark residents, including Blazer and SEED. –Credit: Newark Public Library

A booklet prepared by the BICC in 1967 offering an overview of the various job training programs available to Newark residents, including Blazer and SEED. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Newark activist Ruth (McClain) Rambo discusses the Business Industrial Coordinating Council in Newark in the 1960s. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Explore The Archives

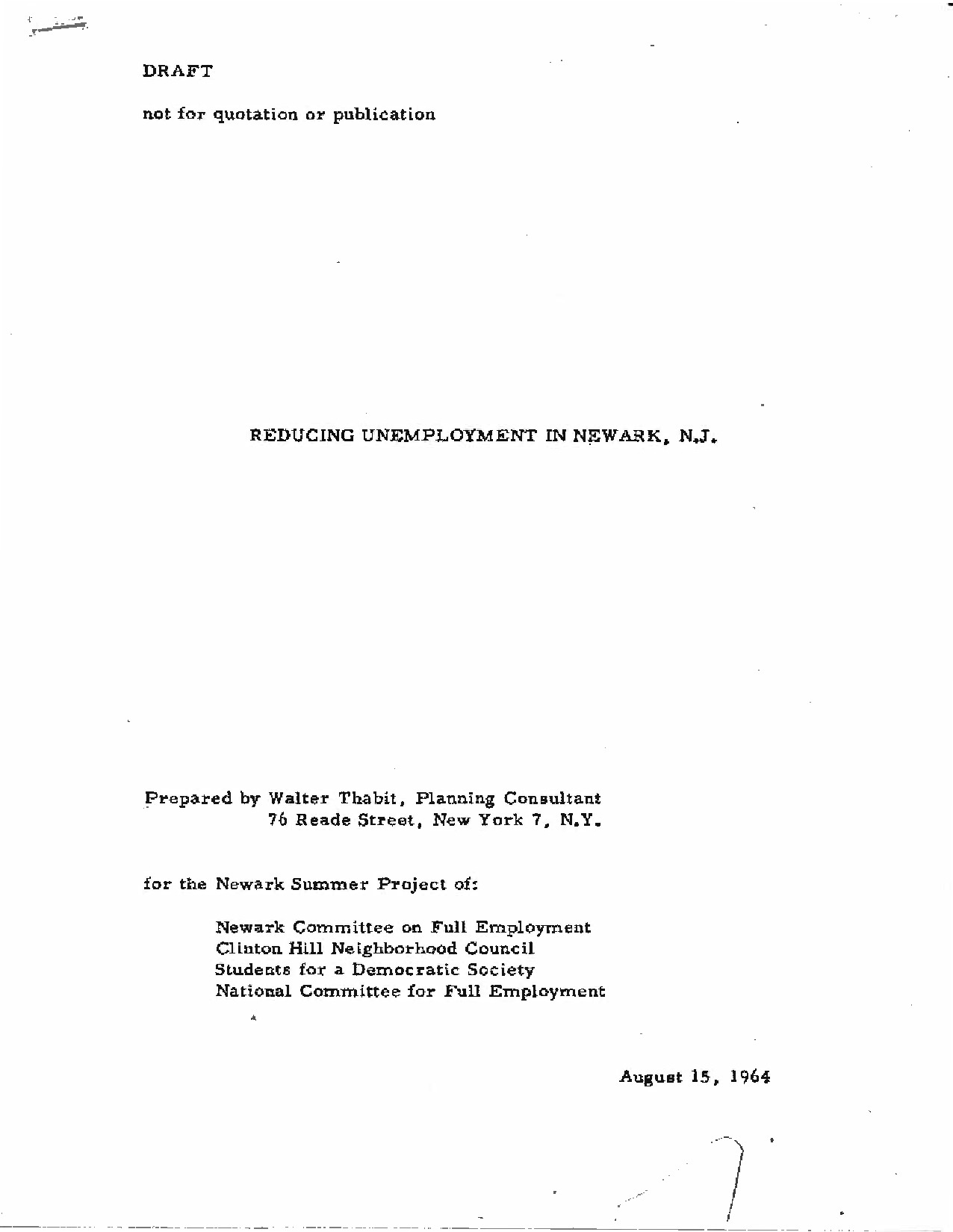

A report titled “Reducing Unemployment in Newark, NJ” prepared in 1964 by Walter Thabit for the Newark Summer Project, a joint undertaking of the Newark Committee on Fully Employment, the Clinton Hill Neighborhood Council, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and the National Committee for Full Employment. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

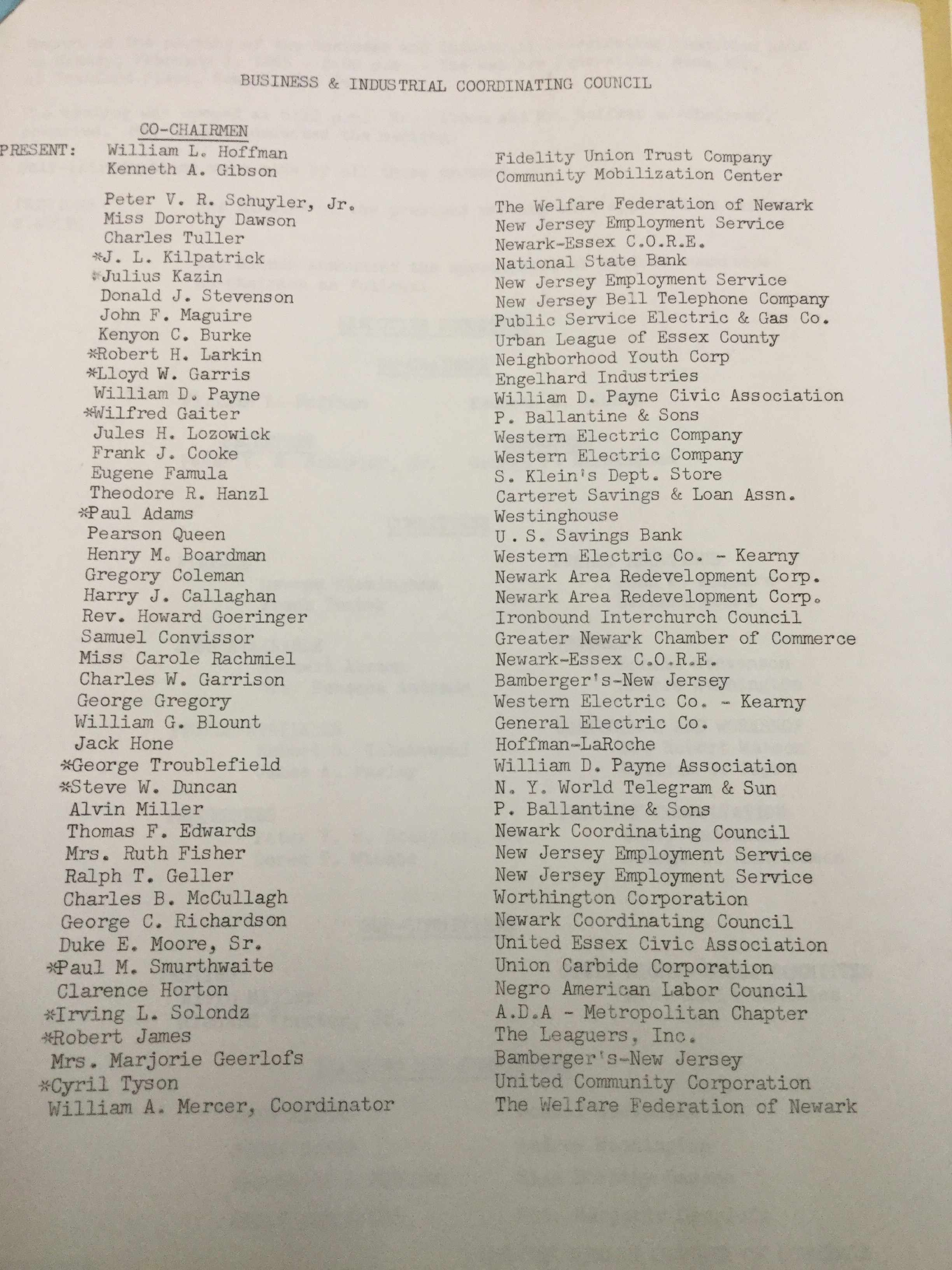

An undated roster of members of the Business Industrial Coordinating Council (BICC). –Credit: Newark Public Library

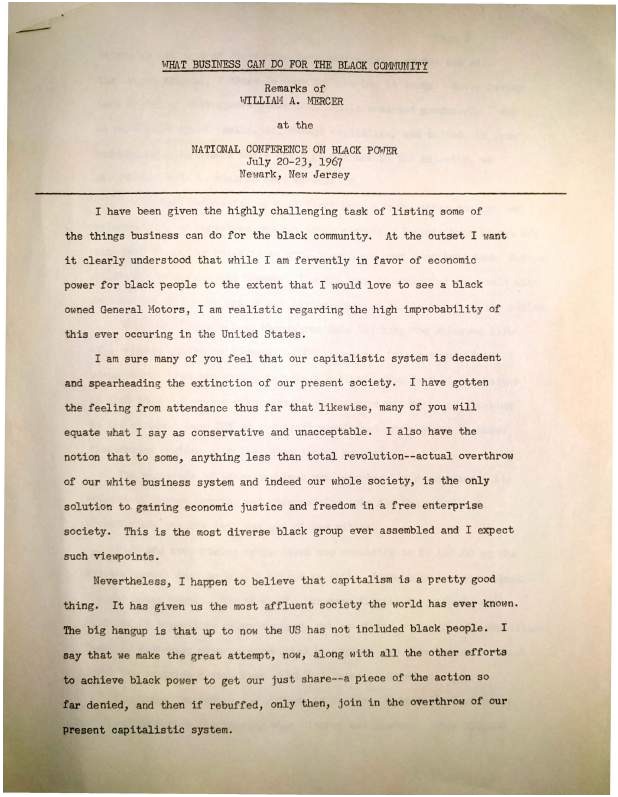

A speech delivered by BICC Coordinator William A. Mercer at the National Conference on Black Power in Newark. The Black Power Conference began just days after the 1967 Newark Rebellion had come to a close and brought a wide array of national Civil Rights and Black Power leaders to Newark. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Ted Pinckney discusses his involvement with the Business Industrial Coordinating Council (BICC) and Interracial Council for Business Opportunity (ICBO) in the late 1960s-early 1970s. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

Veteran activist and politician George Richardson discusses the Building and Industrial Coordinating Council (BICC). –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

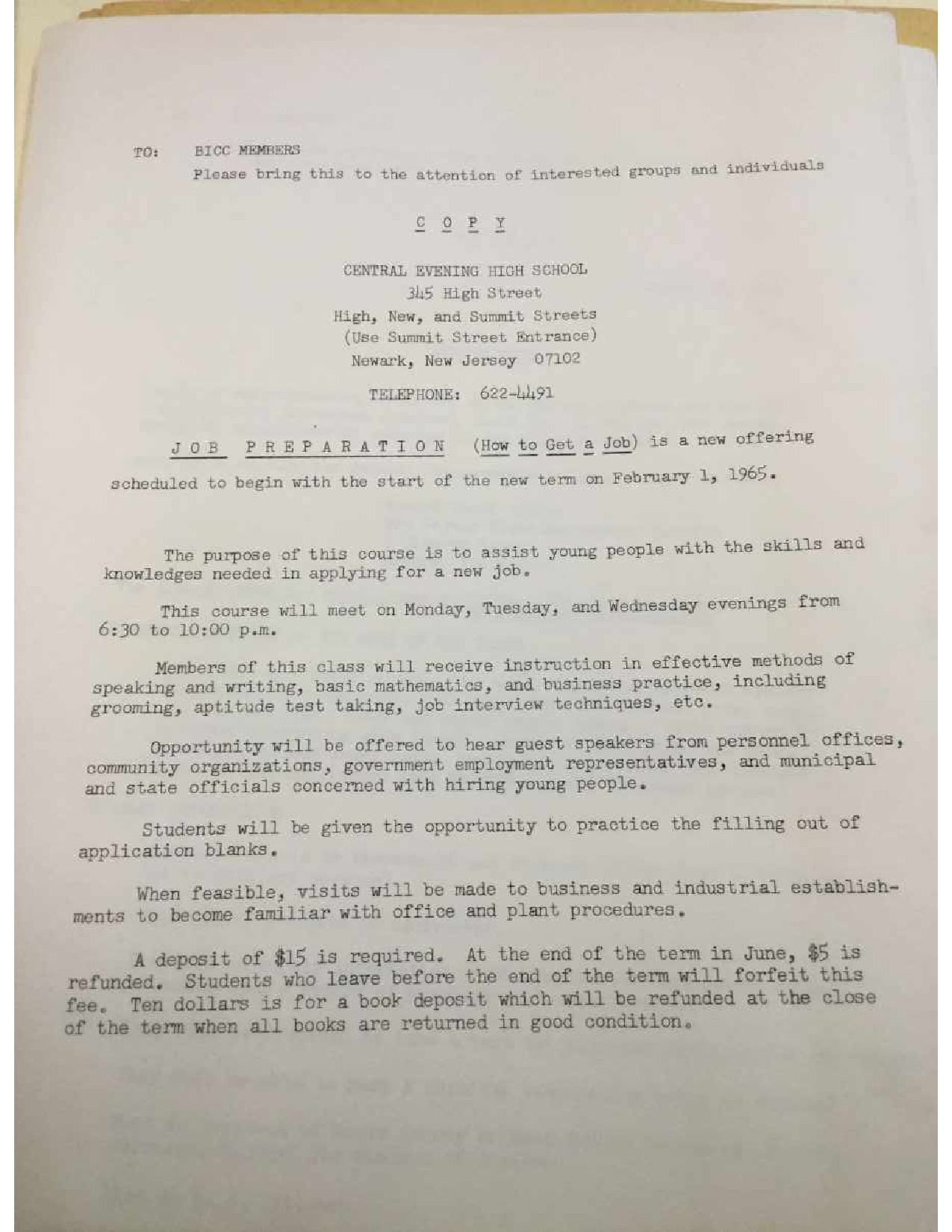

Undated flyer for a job preparation course hosted by the BICC at Central Evening High School. –Credit: Newark Public Library