Cyril Tyson

Cyril Tyson arrived in Newark in January, 1965 to help initiate and organize the United Community Corporation (UCC), the city’s War on Poverty agency (a Community Action Agency funded by the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964). The Act was signed by President Lyndon Johnson in August of 1964 as part of his War on Poverty program, and funded the establishment of local Community Action Agencies to provide federal support for local efforts to combat poverty.

Tyson was originally contacted by Timothy Still, member of the UCC Board of Trustees and the Hayes Homes Tenants’ League, to inquire about Tyson’s possible interest in directing the newly-formed UCC. When Still contacted him, Tyson was the executive director of HARYOU-ACT, an anti-poverty program in Harlem and precursor to the Economic Opportunity Act. Tyson had also been project director of Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited, Inc.’s (HARYOU) landmark study of juvenile delinquency and youth crime, which published its findings in the report Youth in the Ghetto: A Study of the Consequences of Powerlessness and a Blueprint for Change.

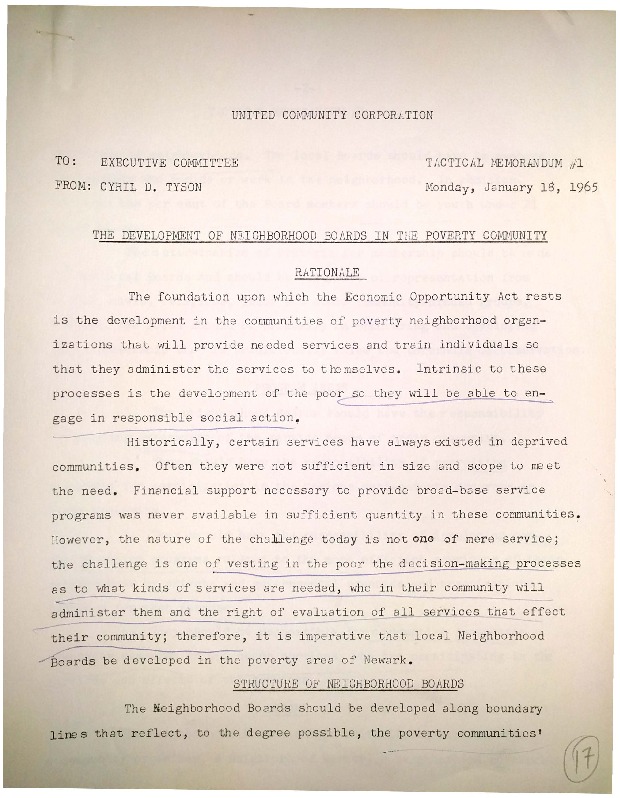

Although hesitant to leave his position with HARYOU-ACT, Tyson eventually agreed to become the first Executive Director of the UCC, effective January 1, 1965. Tyson made it clear, however, that his intention was to only hold the position temporarily in order to develop the UCC’s organizational structure and establish local leadership. Tyson’s plan for the UCC adopted the model of decentralized Area Boards. Under his vision, there would be nine Area Boards, each with a separate Board of Directors and a budget for staff and programs. The goal of this structure was to promote “maximum feasible participation” of the poor within the anti-poverty program.

In addition to the Area Board structure, Tyson also assisted in the development of Community Action Programs (CAP) to aid and empower the city’s poor, predominantly Black and Puerto Rican populations. Under his direction, CAPs such as the Blazer Work Training Program, Newark Legal Services Project, and High School Head Start were established with representation and direction from the local Area Boards.

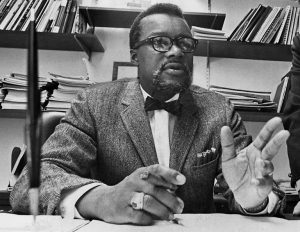

During his 20-month term as Executive Director, Tyson oversaw the expansion of the UCC funding base from an initial $184,000 federal grant to over $7 million in federal funds. The growth of the UCC was not without controversy, however, as Newark city officials and residents struggled for control over the anti-poverty agency and its programs. Frustrated by Tyson’s resistance to demands for patronage, city officials, including councilmen Frank Addonizio and Lee Bernstein, launched an investigation into the UCC in 1965. The councilmen issued a report condemning Tyson’s hiring of non-Newark residents for leadership positions in the UCC, though these individuals made up a small minority of the UCC’s staff.

Cyril Tyson resigned in September, 1966 after outstaying his initial pledge of one year of service. “I said that, in my mind,” Tyson recalled, “the UCC weathered the political storm, survived the City Council Investigation, and proved that united community leadership could initiate and implement a creative and sound program.” Although federal funding proved to be short-lived and insufficient to create substantial and sustainable economic change in the city, the struggle for control of the UCC that Cyril Tyson helped to establish, provided a significant experience in the empowerment process of many Black and Puerto Rican residents in Newark.

References:

Cyril Tyson, 2 Years Before the Riot!: Newark, New Jersey and the United Community Corporation 1964-1966.

UCC Press Release on Resignation of Cyril Tyson (July 28, 1966)

Newark residents, politicians, journalists, and civil rights activists reflect upon their experiences with Cyril Tyson and the United Community Corporation (UCC) in the city from 1965-1966. (See Vimeo link for credits)

Tactical memo from Cyril Tyson on January 18, 1965, in which he describes plans for organizing area boards to promote community involvement in the UCC. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Report published by the United Community Corporation (UCC) to provide an overview of the agency’s Community Action Programs from 1965-1966. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Press release from the United Community Corporation on July 28, 1966, announcing Cyril Tyson’s resignation as executive director. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries