Part 3: New Directions in Black Politics

The 1967 Newark Rebellion ended after five days of violence, death and destruction. But as the heat from the embers of the fire slowly dissipated, and the afterglow of the dying flames still lit the skies over the city, some of the people who saw a significant change in the power relations amongst black and white people began to see opening and opportunities that didn’t exist before July 1967. For months after the Rebellion, there was a power vacuum in Newark, as stunned city, state and federal officials tried to figure out what to do next. And before the power recovered, new leadership emerged with new ideas about how to move the demands of Newark’s black community forward. Some of the older advocates, like those in the United Community Corporation (UCC), the city’s War on Poverty Program, demanded more federal dollars, which was okay, but not enough for those who wanted more than just additional antipoverty dollars.

And so they turned their eyes to the proposed medical school, and devised new ways to organize the community to stop the land grab, using the memory of the Rebellion, which nobody planned and few people wanted, for political leverage. These activists and organizers used the violence that the Rebellion represented as a way to extract housing, jobs, access to new federal dollars, better health care for the people of Newark….and ultimately as a springboard for the election of the first black mayor in 1970.

Explore The Archives

Clip from a 2007 panel discussion of Sandra King’s documentary film “Newark: The Slow Road Back,” in which Clement Price describes the historical significance of the 1967 Newark rebellion. Dr. Price argues that the rebellion was “the defining moment of Newark’s 20th Century.” — Credit: “Newark: The Slow Road Back,” Sandra King

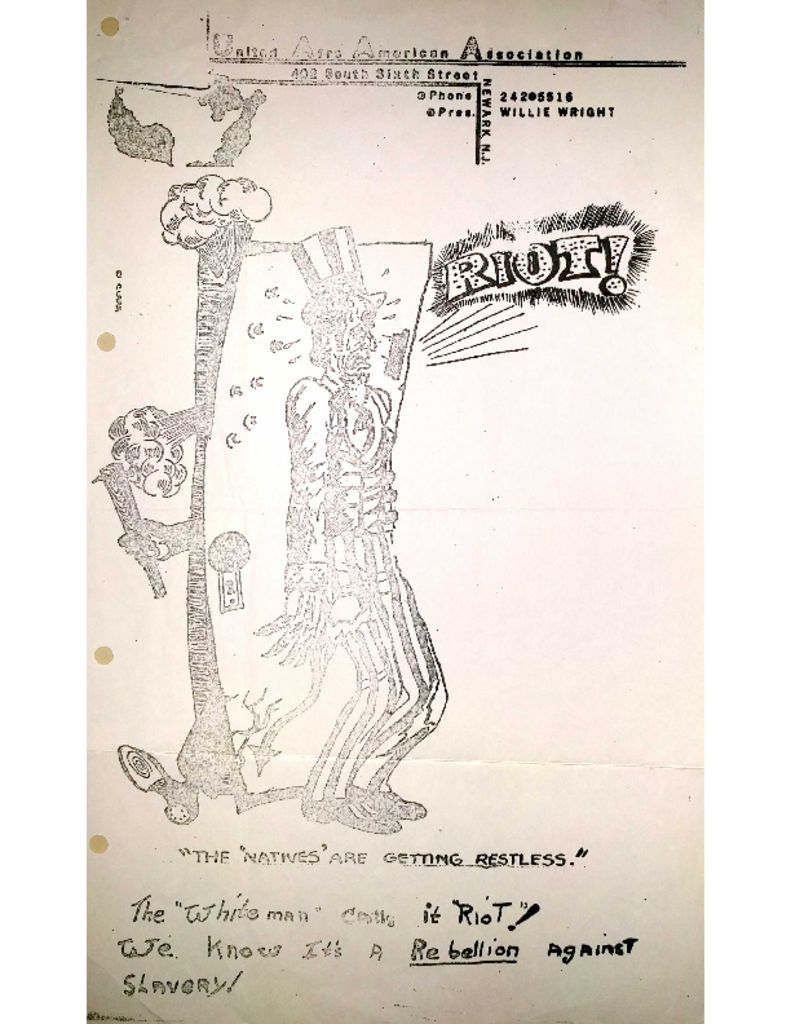

Poster distributed by the United Afro American Association after the 1967 Newark rebellion. The poster depicts Uncle Sam as a devilish figure, yelling “Riot!” as he struggles to hold back a black man with a club. Many in Newark’s Black communities saw the July events as “rebellions” or “uprisings” against oppression, while white communities and politicians viewed them as “riots” against law and order. — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

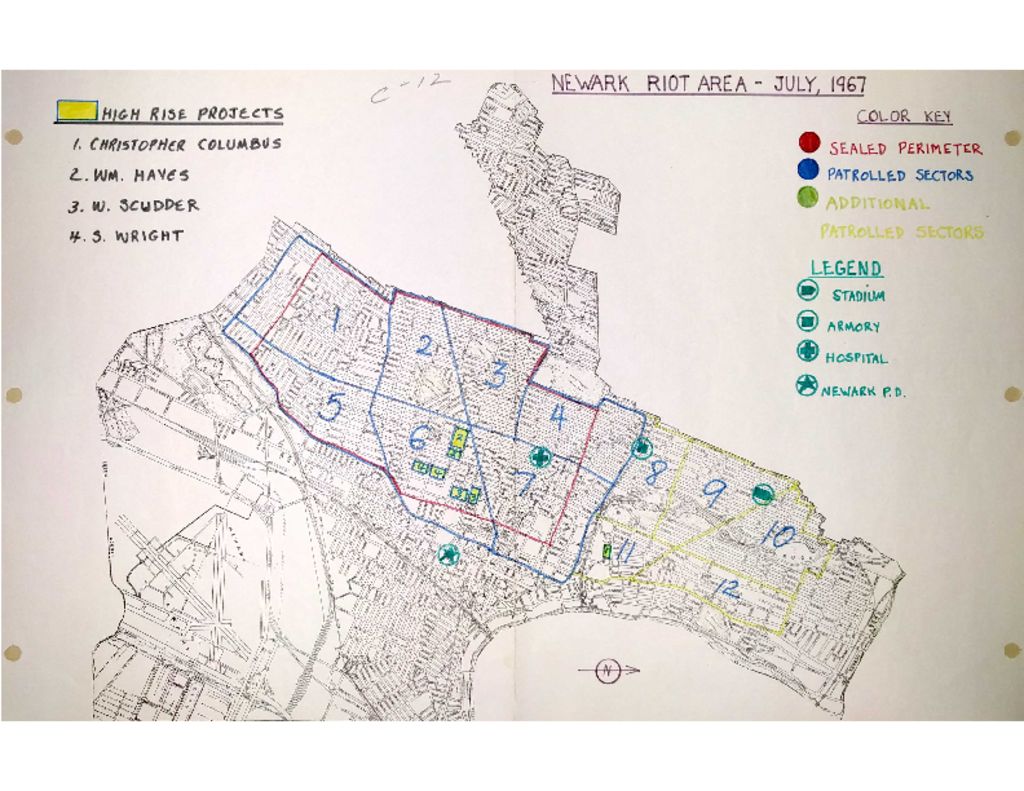

New Jersey State Police map of the “Newark Riot Area- July, 1967” depicting police perimeters, patrols, landmarks, and “high rise projects.” — Credit: New Jersey State Archives