Urban Renewal and the Medical School Fight

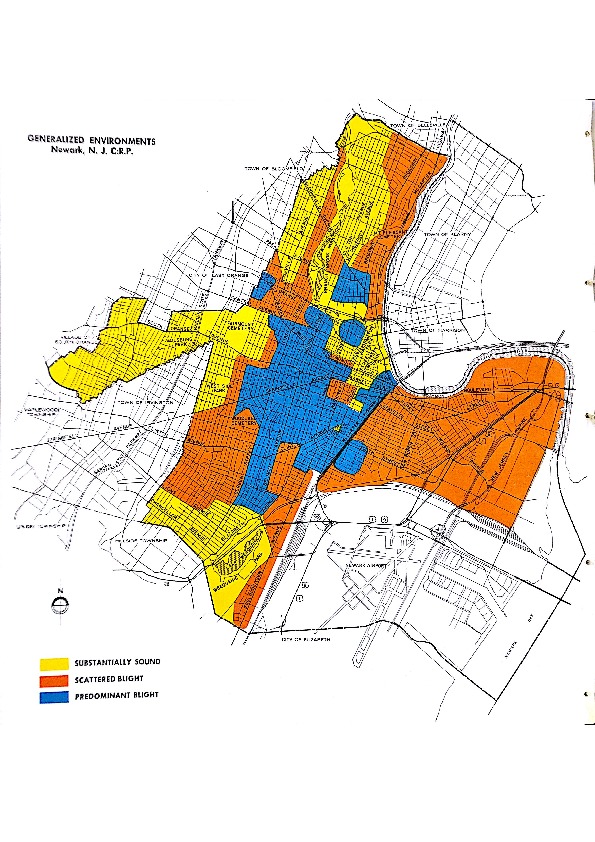

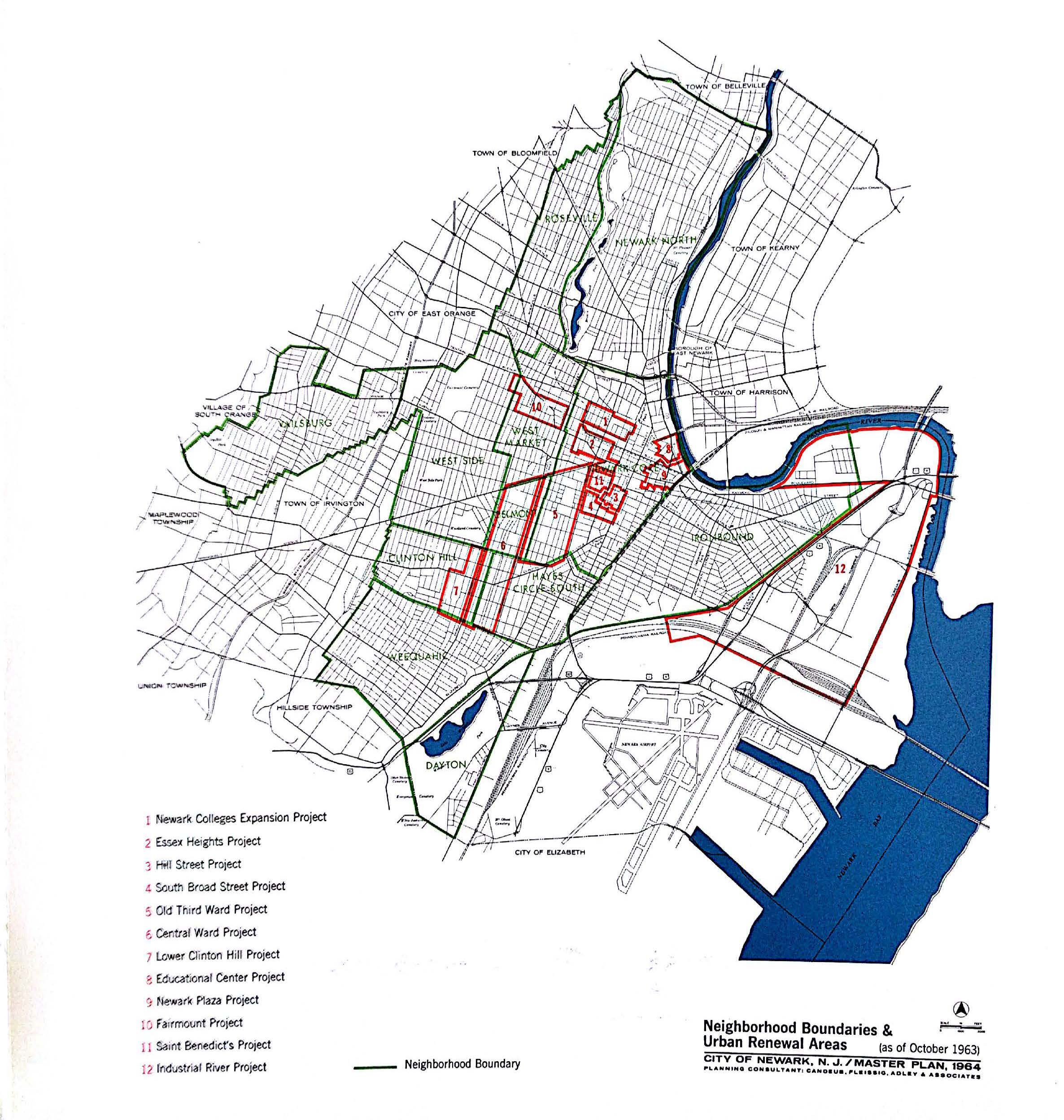

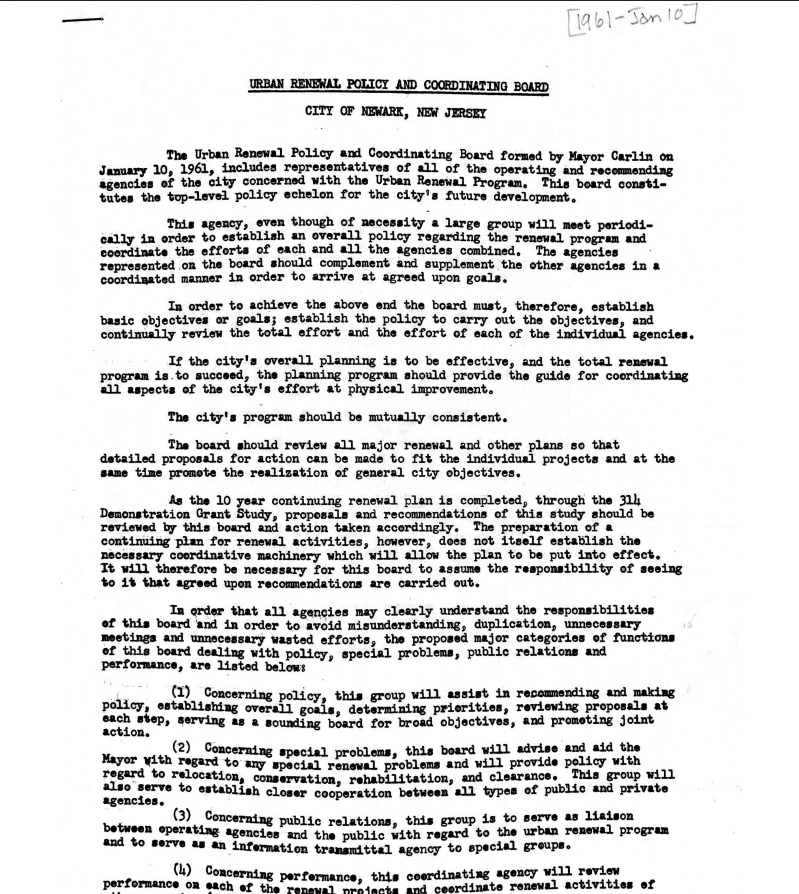

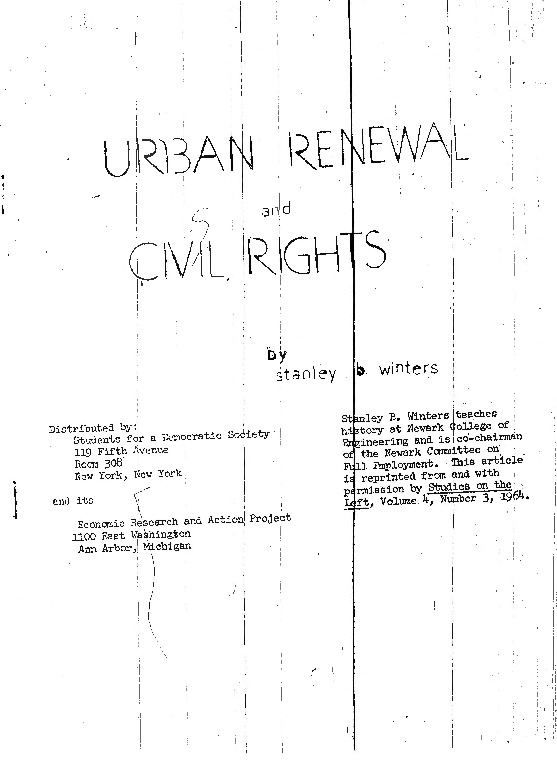

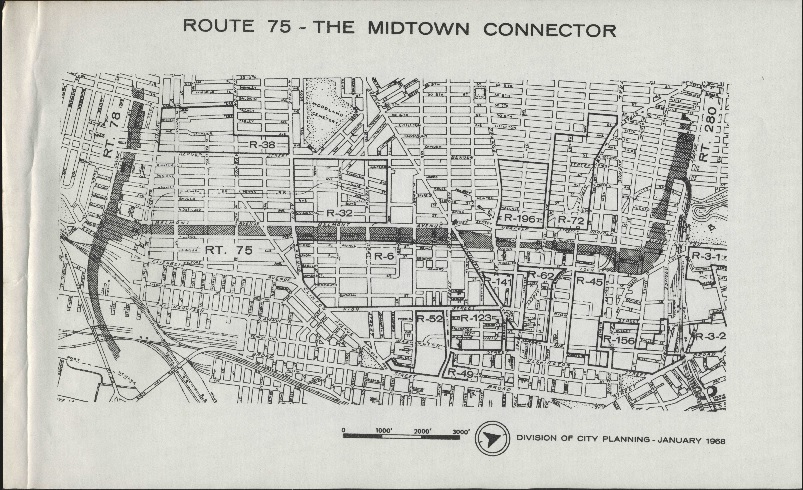

Between 1952 and 1967, there were 17 urban renewal projects in Newark. Newark was the second most “urban renewed” city in the country, behind only Norfolk, Virginia, meaning more federal dollars were poured into Newark to acquire property and demolish buildings than any other city but one. Urban Renewal did not mean construction of new housing and neighborhoods—just vacant land, until somebody decided what to do with it.

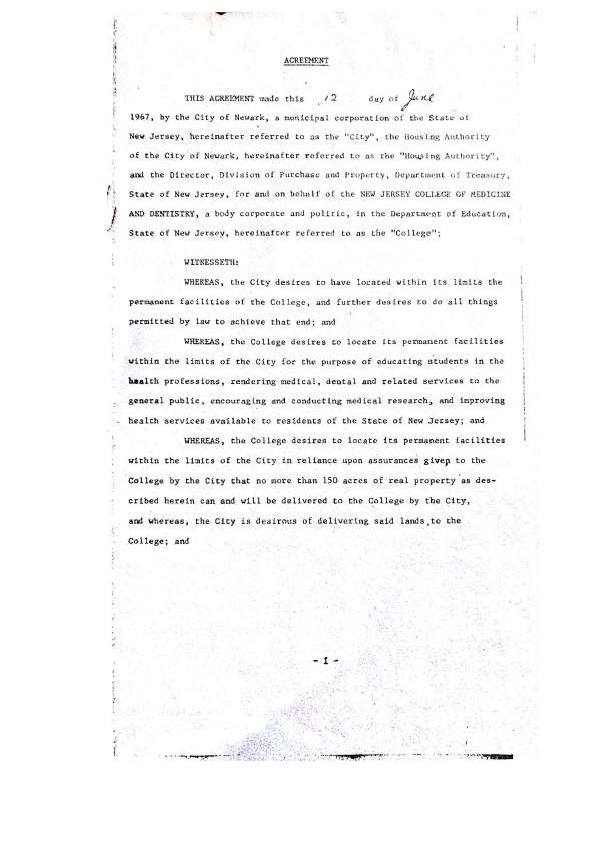

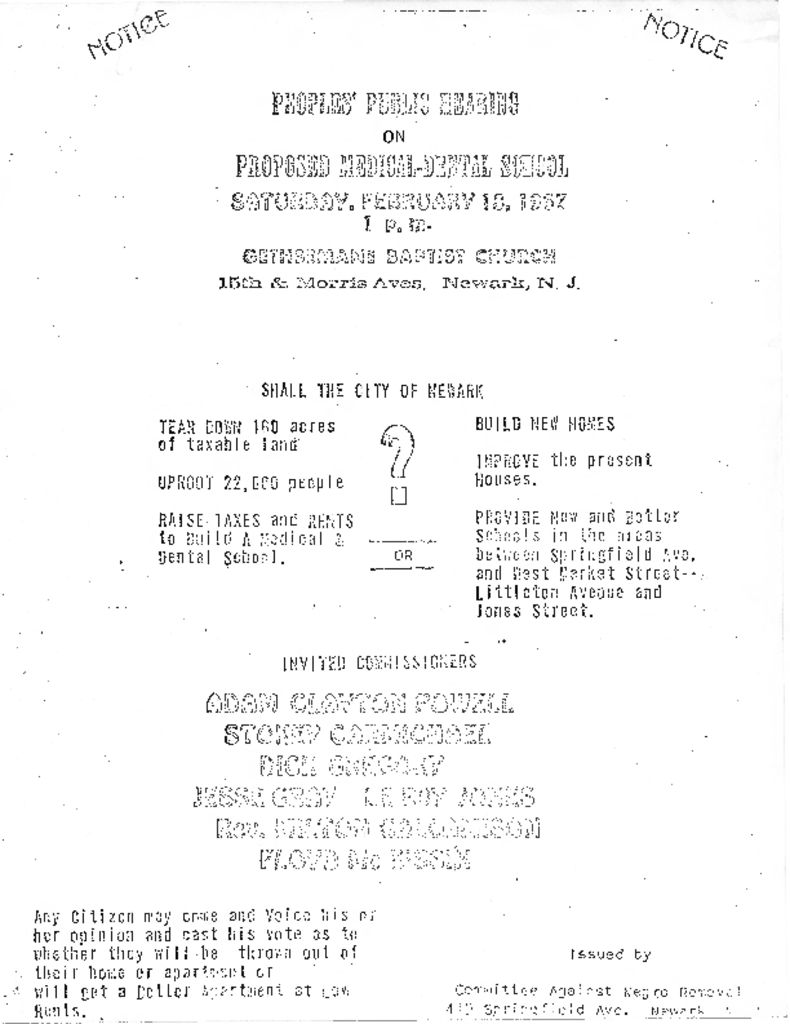

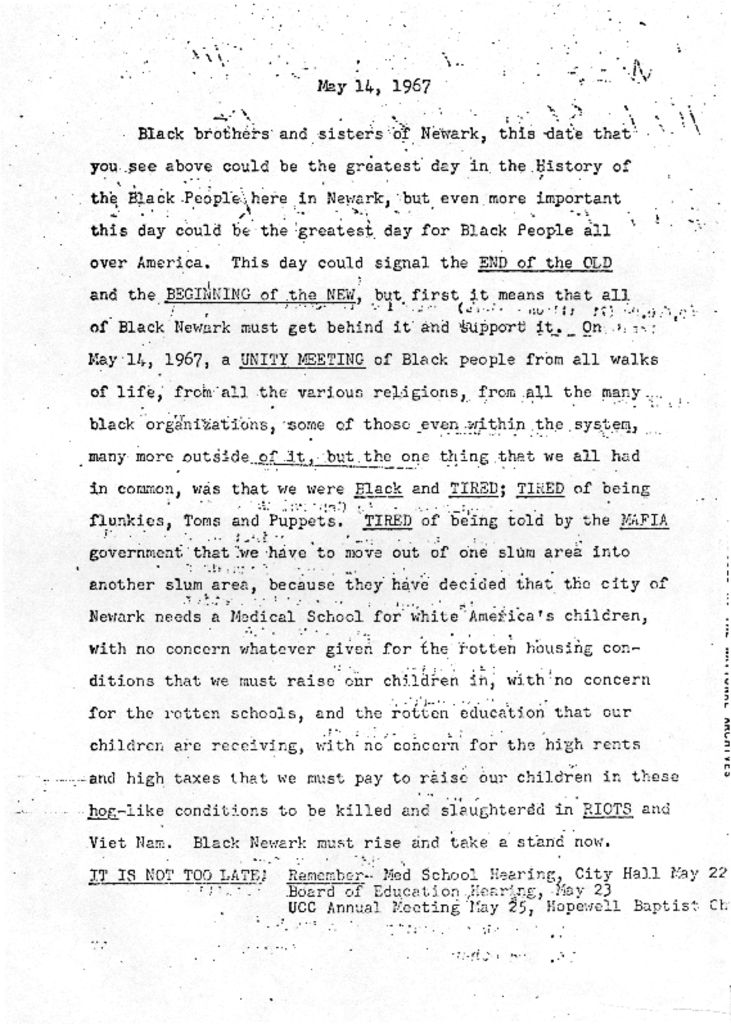

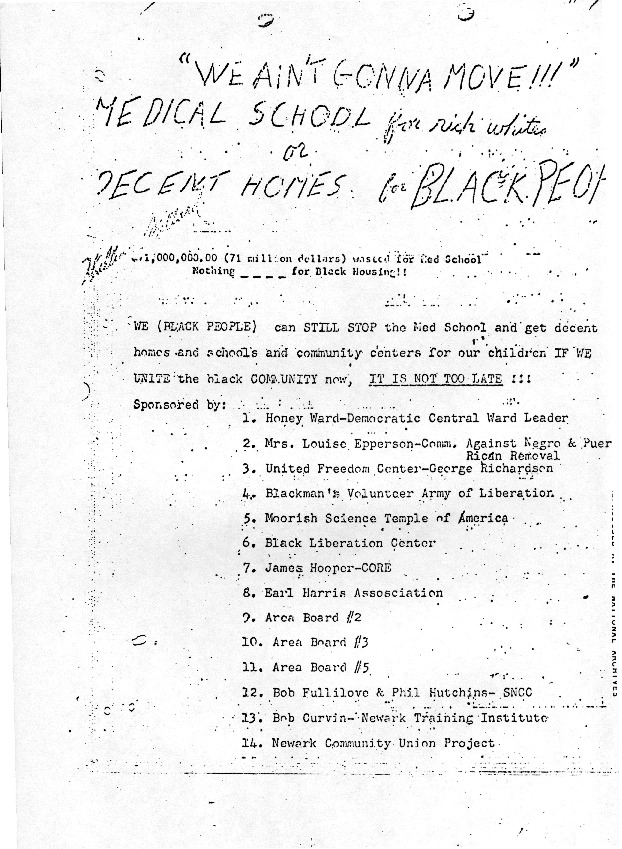

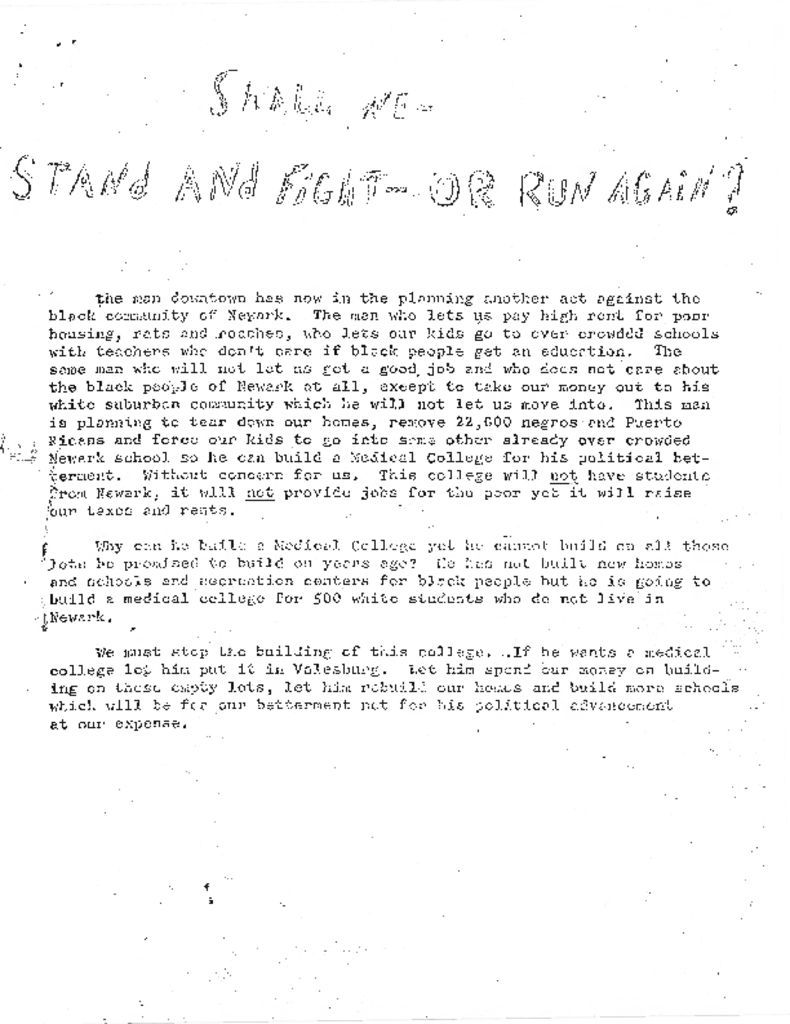

It was not surprising then, that in 1966 and 1967, urban renewal became the central focus of civil rights and neighborhood groups in the Central Ward over plans to build a sprawling new medical school on 200 acres, right in the heart of the city’s most densely populated black community, displacing 22,000 mostly black and Puerto Rican residents. State and school authorities initially planned to build the new school in Madison, New Jersey, a wealthy suburb about twenty-five miles west of Newark. Madison had a black and Hispanic population of less than 5 percent at the time. There has been much speculation as to why Mayor Addonizio immediately launched an all-out effort to put the medical complex in Newark. It may have been his way of attracting attention to become Governor of the state.

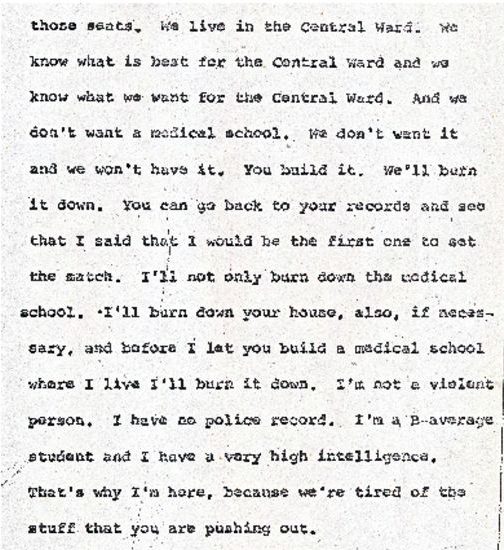

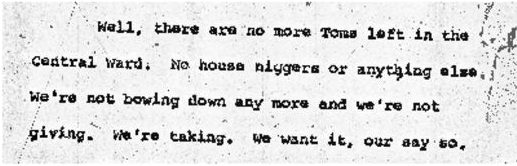

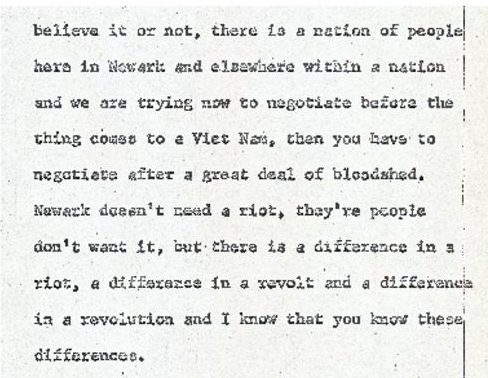

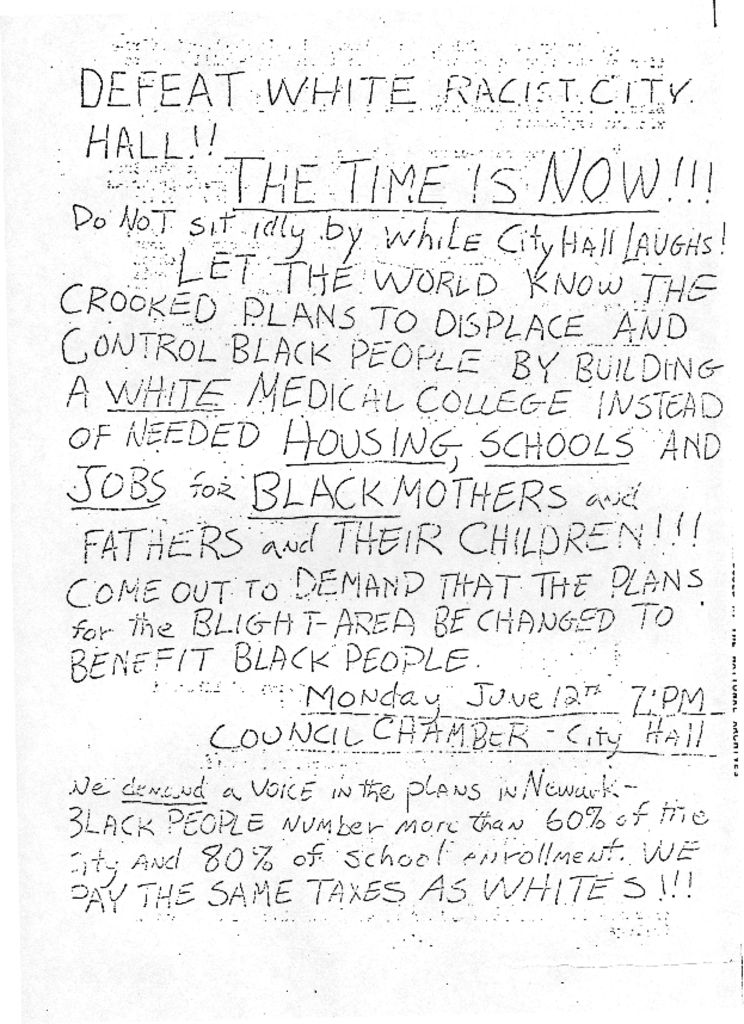

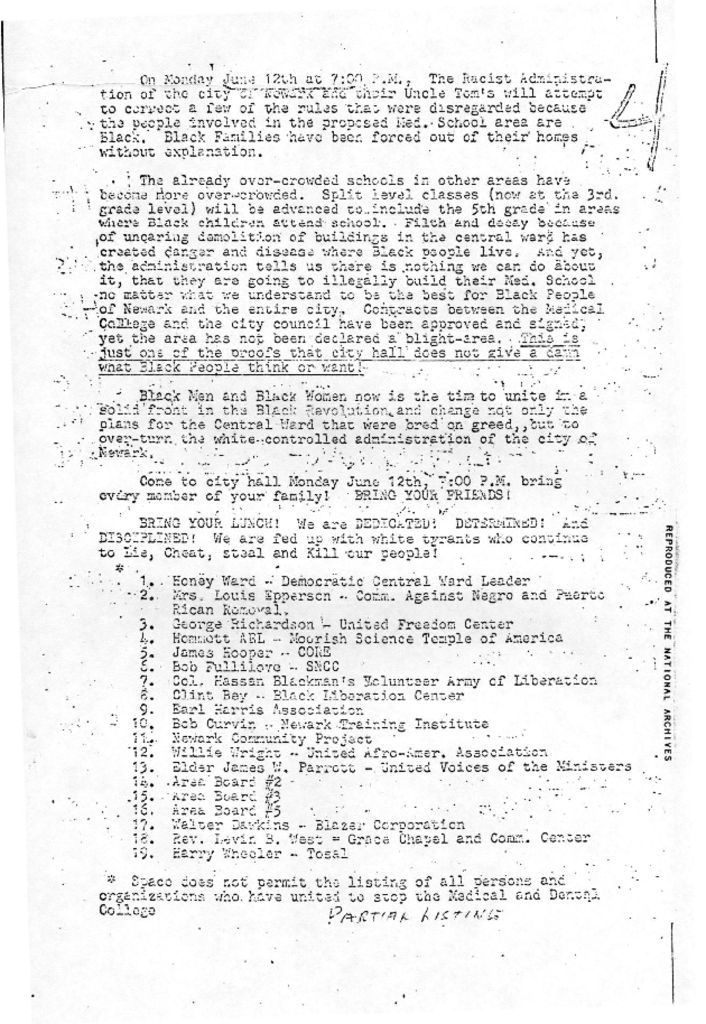

As news of the project circulated, opposition grew. The local chapter of CORE and other individuals and organizations issued public statements criticizing the pledge of land. Assemblyman George Richardson and his Freedom Democratic Party publicly opposed the granting of the land. There were demonstrations, primarily at city hall during the “blight hearings,” which under New Jersey law were required for a declaration of blight as a prerequisite of the taking of the land by the city for the College of Medicine and Dentistry (CMDNJ). African Americans and their supporters flocked to a July 1967 hearing to say “Hell No” in no uncertain terms, led by George Richardson, Jimmy Hooper, Chairman of CORE at that time, Louise Epperson and Harry Wheeler of the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal. Someone named Colonel Jehru Hassan from the Black Man’s Liberation Army, originally from Washington, DC, provided the magic moment at one of the hearings: one of his lieutenants snatched the records of proceedings from the Planning Board Clerk. There was bedlam at the meeting. It was turned out, with a promise of more meetings. More and more people came out to see what would happen next and to see if anyone could top that!

When subsequent hearings were terminated with some people still wanting to have their say, the community sued, claiming violation of their due process rights. However, before the decision was rendered, the city erupted into five nights of rebellion in response to the beating of cab driver John Smith. It is conjectured that the medical school blight hearings was one of the reasons for the anger, and the violence that followed.

References:

Kevin Mumford, Newark: A History of Race, Rights, and Riots in America

Compilation of clips from interviews with Larrie West Stalks, Junius Williams, and Louise Epperson, in which they discuss what “urban renewal” meant to Newark’s Black communities in the 1960s. Plans for “urban renewal” in Newark, including the proposed construction of a medical school and highway through predominantly Black communities, escalated tensions in the city leading up to the outbreak of the 1967 Newark rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from an interview with NCUP member Junius Williams, in which he describes the significance and scenes of the Medical School Blight Hearings. The Medical School Fight and contentious Blight Hearings are credited as one of the precipitating factors of the 1967 Newark rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Explore The Archives

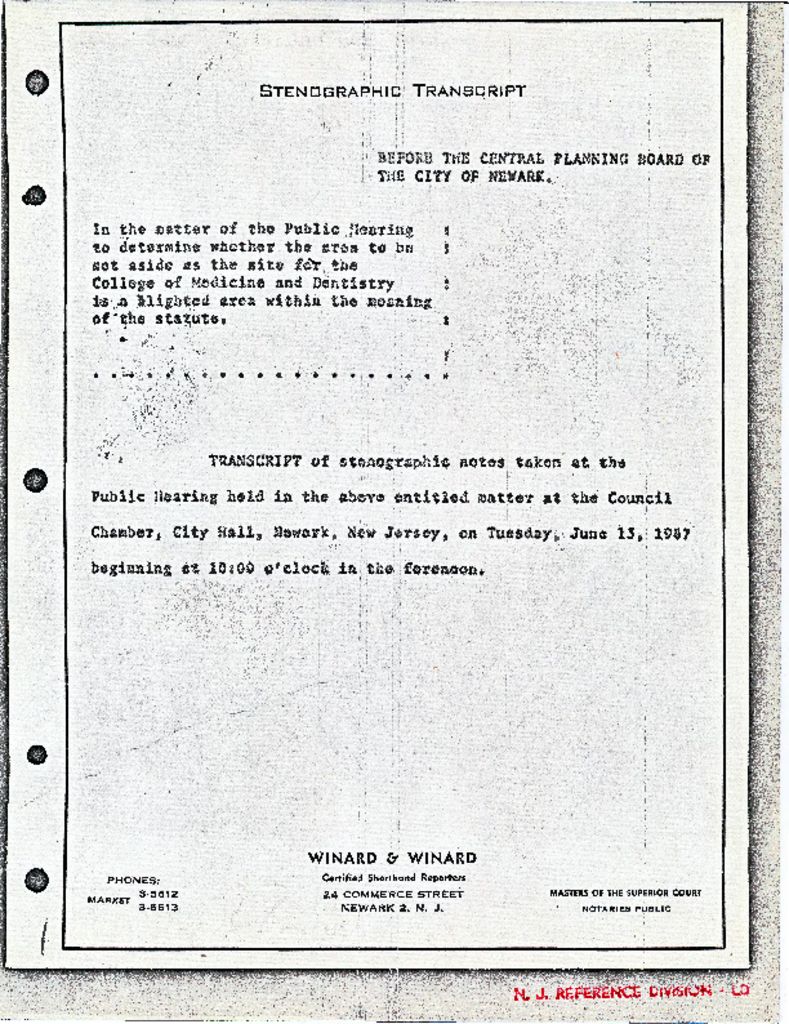

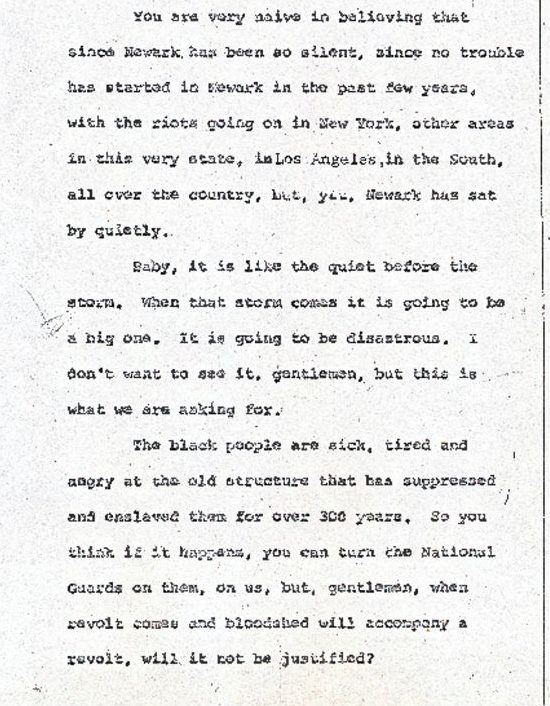

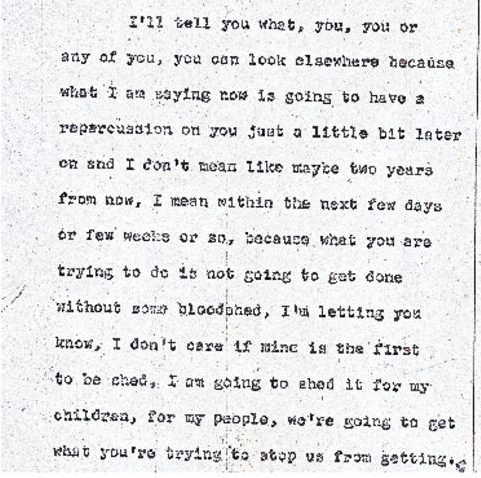

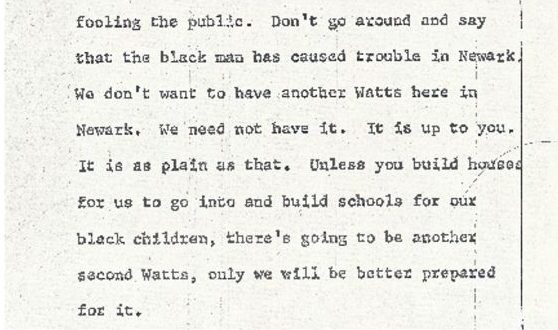

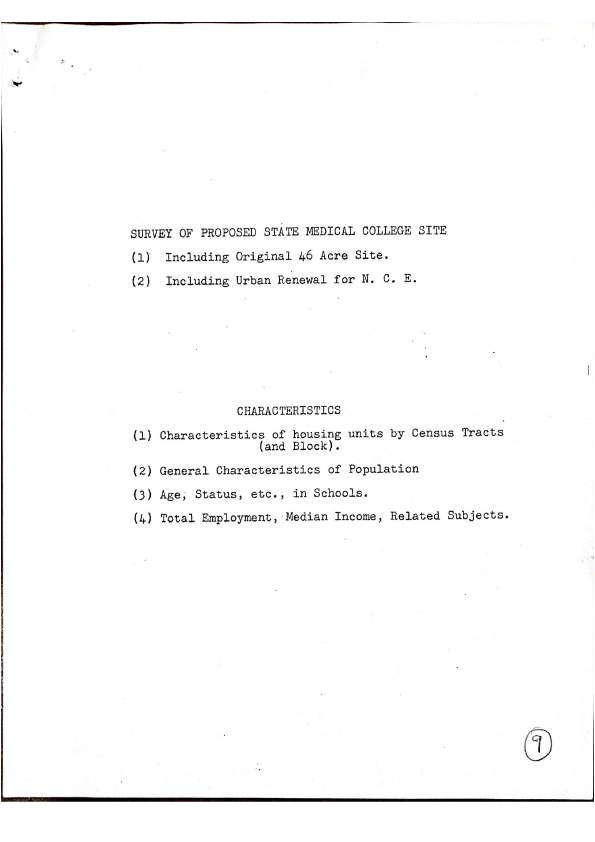

Excerpts from the stenographic transcript of various Newark residents’ comments to the Central Planning Board in June 1967 during the infamous “blight hearings.” These public hearings were held to determine if areas in the Central Ward were “blighted” so that the lands could be taken by eminent domain for the construction of the New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry. These excerpts were selected from over 500 pages of transcripts to illustrate the high tensions and predictions of impending violence in Newark just weeks before the 1967 rebellion. — Credit: Newark Public Library