Transformation of the Black Freedom Movement in Newark

As the Civil Rights Movement reached a pinnacle of success with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, urban Black communities were in a period of flux. In addition to Newark, between 1964 and 1967, urban Black communities across the nation, including Chicago, Watts, and Detroit, experienced dramatic urban uprisings. Televised across the nation, these uprisings introduced many Americans to the lived realities of the Jim Crow North and the awesome destructive power within urban Black communities. The national media coverage of these uprisings led to a national dialogue about the urban dilemma and renewed interest amongst social scientists and policymakers around ways to alleviate urban poverty. In response, President Johnson introduced his signature set of domestic policies: the Great Society, which sought to eradicate poverty and racial inequality.

In 1964, Newark was one of the first cities to apply to receive money from what is commonly known as the War on Poverty, an umbrella term for several programs within the Great Society. The grants the city received to fight poverty were administered locally by the United Community Corporation (UCC). Administered on the national level by the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), the UCC was mandated by the OEO to include “maximum feasible participation of the poor” in the creation and administration of antipoverty programs. Therefore, the monies generated by the War on Poverty bypassed both the mayor and the city council to empower the community instead. The bypassing of city hall was the linchpin in a series of standoffs between the mayor, the city council, the UCC, and members of the community in the mid-1960s. To top it off, the map of UCC’s Area Boards closely resembled the city’s voting districts and was therefore seen by Mayor Addonizio and many City Council members as a direct threat to city hall. These battles for control of policy and money became a vital training ground for Black leaders and the emerging Black political class in Newark and other cities receiving War on Poverty funding.

On the national level, with the election of President Nixon in 1968, the federal government’s approach to the urban crisis shifted. Nixon introduced a new program, Model Cities, which sought to combat urban poverty and challenge cities to experiment with new methods of governing. Having seen how community organizers leveraged the War on Poverty program to support the Black Freedom Movement, Nixon channeled Model Cities funding and operations through local and state governments to throttle community control. So, unlike the War on Poverty’s mandate for “maximum feasible participation of the poor,” the funding for Model Cities went through City Hall and called for only “meaningful citizen participation.”

Gibson’s background as one of the founding board members of the UCC seemed to promise a new vision for the use of federal funds and their relation to the community. Furthermore, his reliance upon the revolutionary spirit of Newark’s community organizations after the rebellion also seemed to promise that the Gibson administration would be marked by the continued growth of community power, sustained in part by the creative use of federal funds. After an initial head start in his first four years, his tenure was instead marked primarily by the use of federal monies not as a means to finance continued opportunity for community empowerment but as a much-needed source of city funding.

Despite Nixon’s general antipathy toward the Black Freedom Movement, Gibson was able to raise funds from the federal government through the Model Cities program. The program was initially led by Junius Williams, the leader of NAPA, which fought against the displacement and exploitation of African American communities through urban renewal in Newark. Under Williams’ leadership, the Model Cities program gave grants to some of the community organizations that were active in the Black Freedom Movement, such as Newark Welfare Rights Organization; and was honored by HUD for conducting the best “Project Rehab” in the nation through the specially created Newark Housing Development and Rehabilitation Corporation.

While Gibson’s election seemed to realize one of the critical goals of the Black Freedom Movement in Newark—the political empowerment of the African American community—many of the key organizations associated with the movement were inactive by the end of his first term. These organizations, including the Newark Area Planning Association (NAPA) and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), had also helped get Gibson elected. The Committee for a Unified Newark (CFUN), an organization founded by Amiri Baraka that brought together Black leaders from across the city to form a Black united front for political power, had lost its close relationship with Gibson. The long battle over the construction of Kawaida Towers, during which he received very little support from Mayor Gibson, in many ways marked the decline of Baraka’s broad-based support in the city. Instead Baraka was actively building the Congress of Afrikan People on both the local and national levels. Robert Curvin, former chair of CORE and the Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention, did not take a position in the Gibson Administration, choosing instead to pursue a doctoral degree at Princeton University. Fred Means, another leading member of CORE, had become a leading force in the Organization of Negro Education (ONE). Moreover, on the national level CORE was experiencing an ideological shift to Black Power that changed the national makeup of the organization. These changes meant that CORE lost its white membership, which was integral to its base in Essex County.

Amid this decline in local grassroots organizations, Junius Williams was ousted as Newark’s Model Cities director. A public battle over an audit of the Model Cities Program, which eventually revealed no misuse of funds, was used by Gibson as an excuse to ask Williams to resign. When Williams refused to resign, Gibson fired him. After Williams’ ouster, Gibson did not mount any real effort to put federal money into the advocacy, training, and empowerment of the communities that worked to get him elected.

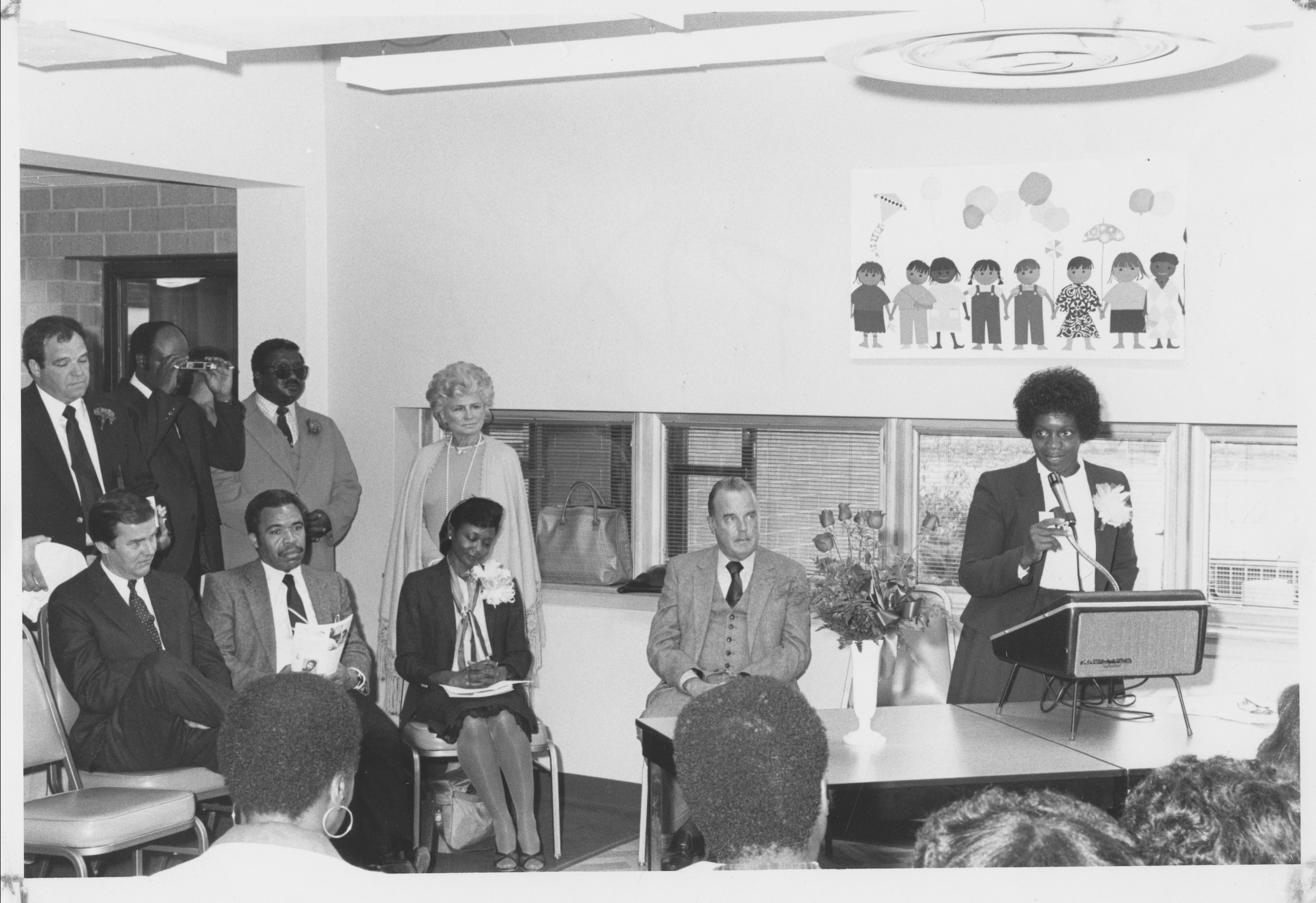

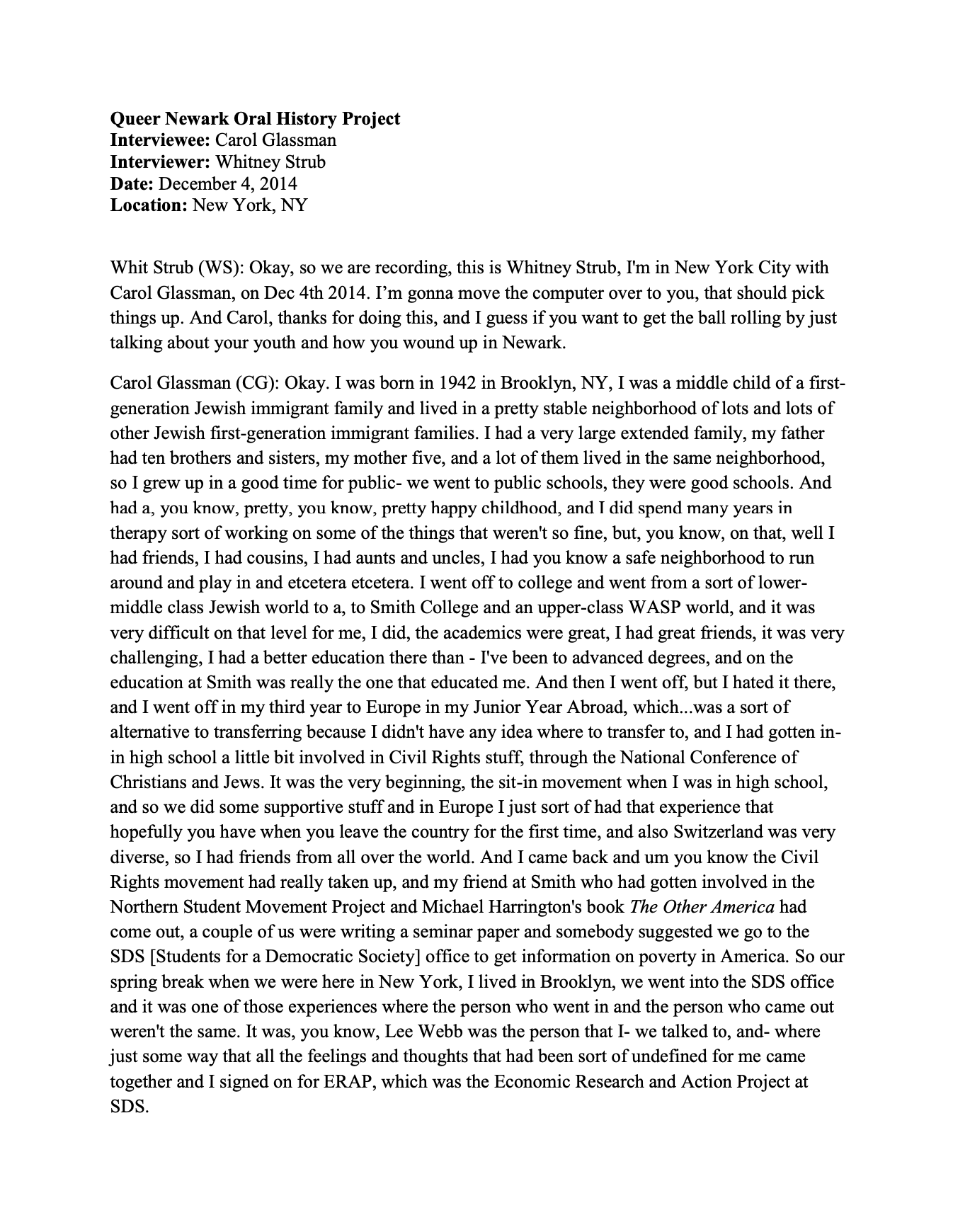

While the organizations that had made up the core of Newark’s Black Freedom Movement faded during this period, the UCC weathered the changes in federal policy and the social climate by abandoning its community action orientation for a social services model. Alternatively, the New Community Corporation (NCC), a community-based organization created in association with the Queen of Angels Church, grew more substantial and more prominent. Using a combination of private and public monies, NCC developed housing for the residents of the Central Ward and answered the community’s calls for a daycare center. Babyland was spearheaded by Mary Smith, who got her start as a tenant organizer before joining one of the UCC area boards during the War on Poverty. Like the NCC, the Ironbound Community Corporation (ICC) was also an outgrowth and response to the shift away from the politics of confrontation and sought community development to mainly provide services. Many of the early ICC staff members were white activists from the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP), including Carol Glassman and Steve Block, who began working in a white working-class neighborhood after interracial organizing became untenable following the 1967 Rebellion. In 1969, the ICC founded its first program, a preschool, and throughout the 1970s, it continued to develop both an activist agenda focusing on the issues of environmental justice and community development, mainly through its community learning centers.

Ultimately, in one sense, the Black Freedom Movement in Newark had succeeded. Electoral politics had been seen as the next stage of the struggle for Black empowerment in the late 1960s, and Newark’s Black and Puerto Rican communities had accomplished their goal. However, if the promise of electoral politics was the empowerment of the masses of everyday African Americans, then the objective it had organized around had not been achieved. There were many political and economic forces acting against this mass empowerment of Black communities, making local electoral politics insufficient for achieving Black liberation.

Nixon’s election had heralded the emergence of a national backlash against the past decade of Black-led struggles for political, economic, and social justice and empowerment. As the federal government decreased its investment in community development, it increased its investment in policing. This period marked the shift from federal-state interest in the welfare of its citizens to hyper-investment in the politics of law and order, devastating Black communities in the decades since.

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Mark Krasovic, The Newark Frontier: Community Action in the Great Society

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

Bret A. Weber and Amanda Wallace, “Revealing the Empowerment Revolution: A Literature Review of the Model Cities Program,” Journal of Urban History 38, no. 1 (January 2012): 174, https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144211420653.

Komozi Woodard, A Nation Within A Nation: Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Black Power Politics

A short documentary chronicling the United Community Corporation (UCC), Newark’s War on Poverty agency, from 1965-1966. See Vimeo link for full credits.

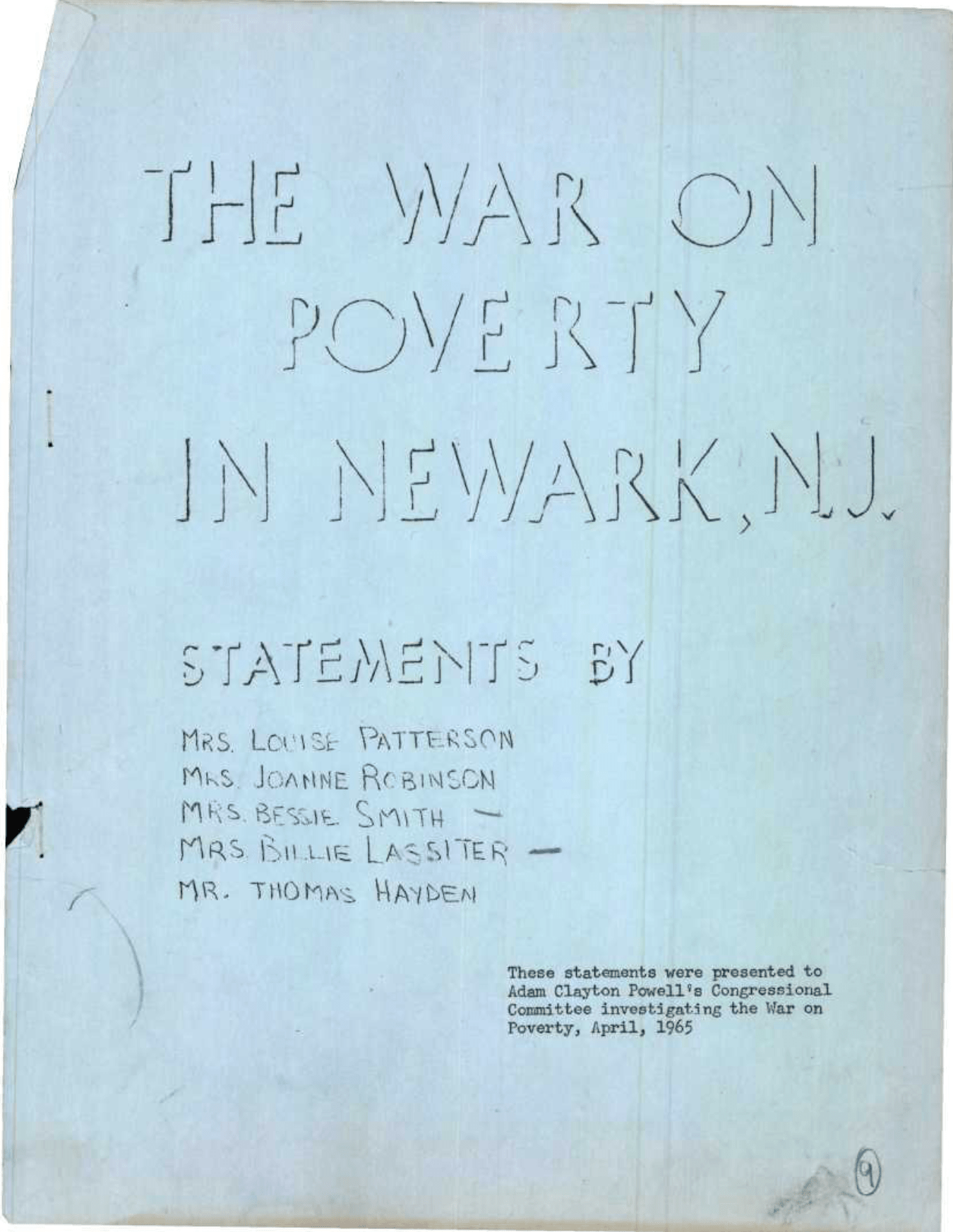

Statements presented to Adam Clayton Powell’s Congressional Committee investigating the War on Poverty in Newark, April 1965. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Clip from a 1988 interview with Congressman John Conyers, in which he discusses the fate of the Civil Rights Movement and American cities under the Nixon Administration. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

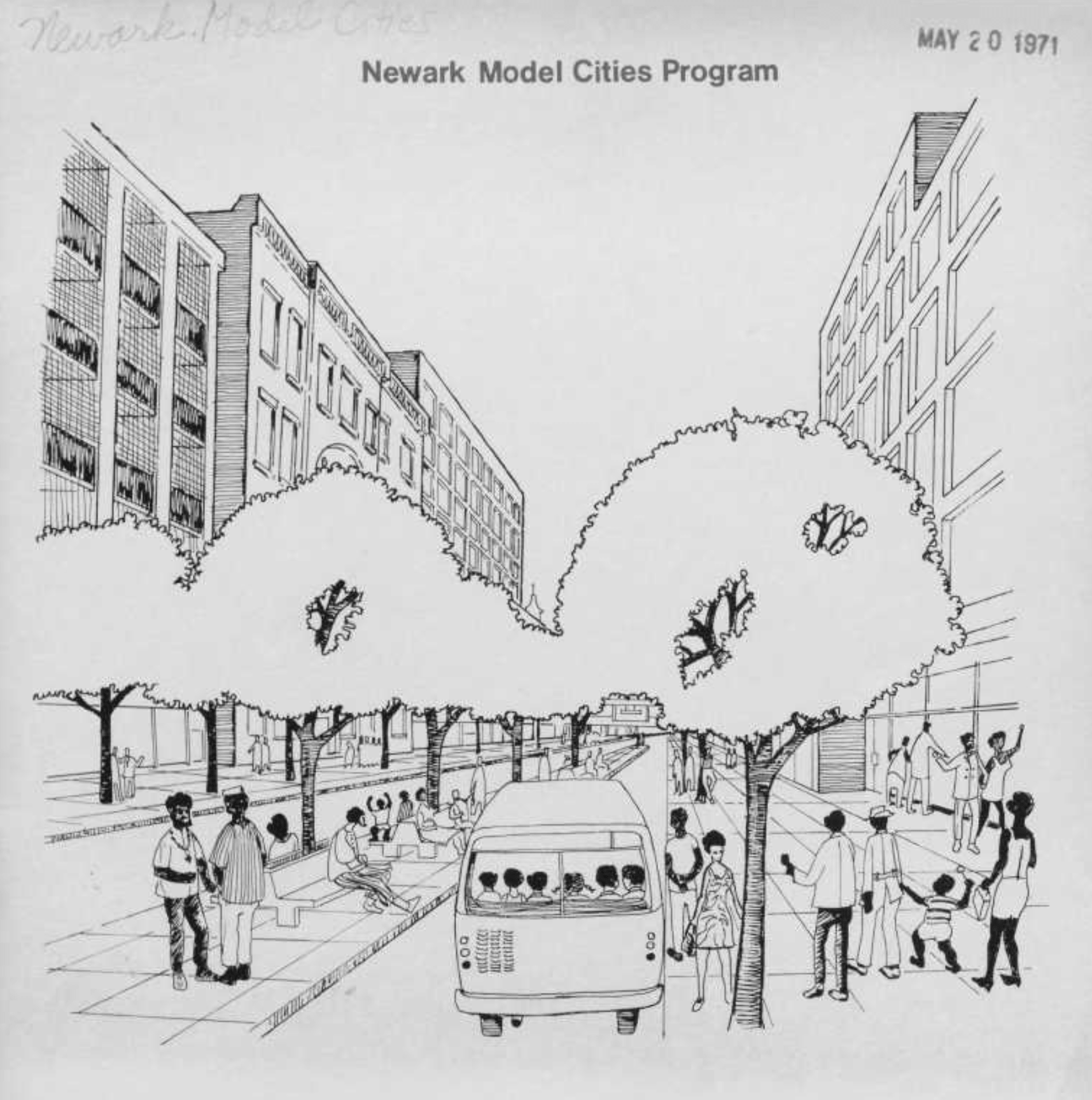

A booklet detailing the Model Cities programs in Newark.

Amiri Baraka explains how his relationship with Ken Gibson changed following the 1970 election in this 2009 oral history interview with Bob Curvin. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

Mary Smith (right) addresses a community meeting at Babyland, as Mayor Ken Gibson (seated, second from left) and others look on and listen. –Credit: Newark Public Library

An interview with Ironbound Community Corporation organizer Carol Glassman, in which she details the shift of white activists to organizing in white community with the rise of Black Power. –Credit: Queer Newark Oral History Project

An interview with Ironbound Community Corporation organizer Carol Glassman, in which she details the shift of white activists to organizing in white community with the rise of Black Power. –Credit: Queer Newark Oral History Project

Explore The Archives

Conference paper prepared by Bessie Smith regarding “maximum feasible participation” of the poor in the United Community Corporation, Newark’s Community Action Agency through the War on Poverty. –Credit: Newark Public Library

A press release from 1967 defending the work of the UCC against the attacks of city officials. –Credit: Newark Public Library

A flier for a trip to Washington D.C. to call on President Johnson to help Newark. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Edition of monthly newsletter circulated by the Model Cities Program, August 1969. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Richard Nixon discussing Black Power during a televised interview. Under the Nixon administration, the federal government clamped down on Black dissent while promoting Black capitalism. –Credit: HornetsNation Charlotte

Richard Nixon discussing Black Power during a televised interview. Under the Nixon administration, the federal government clamped down on Black dissent while promoting Black capitalism. –Credit: HornetsNation Charlotte

The document detailing the finding of 15 month review of the expenditures of the Model Cities Program in Newark. –Credit: US Office of Accountability

Hearing with the Subcommittee on Banking and Currency in the House of Representatives on the Model Cities Program in Newark. –Credit: ProQuest Congressional

Flyer from Ironbound Community Corporation program publizing an event sponored by the Black Women’s Health Organization. –Credit: Newark Public Library

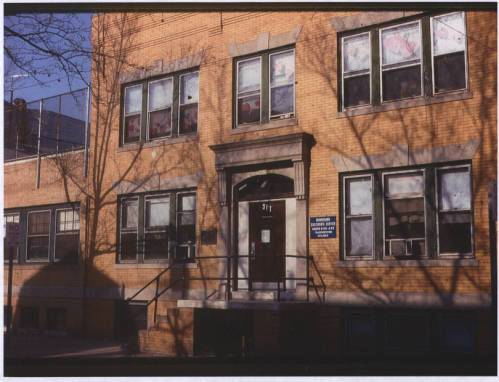

Photo of one of the locations of the Ironbound Childrens Center. The center was the first program established by the Ironbound Community Corporation. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Brochure from 1970s describing the programming of the Ironbound Community Corporation. –Credit: Newark Public Library

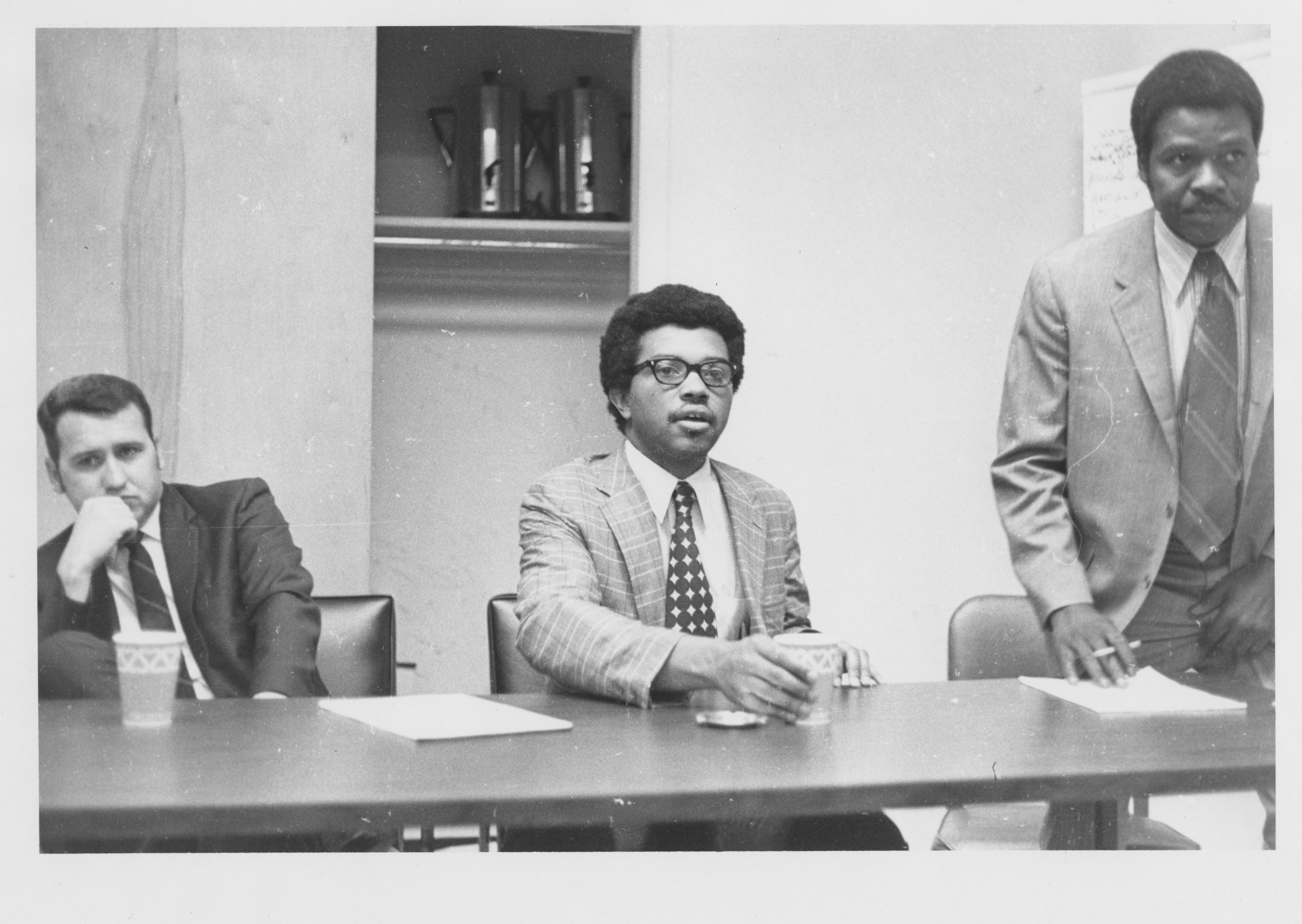

Undated photo from a Model Cities meeting in Newark. Model Cities director Junius Williams is seated in the center. –Credit: Newark Public Library

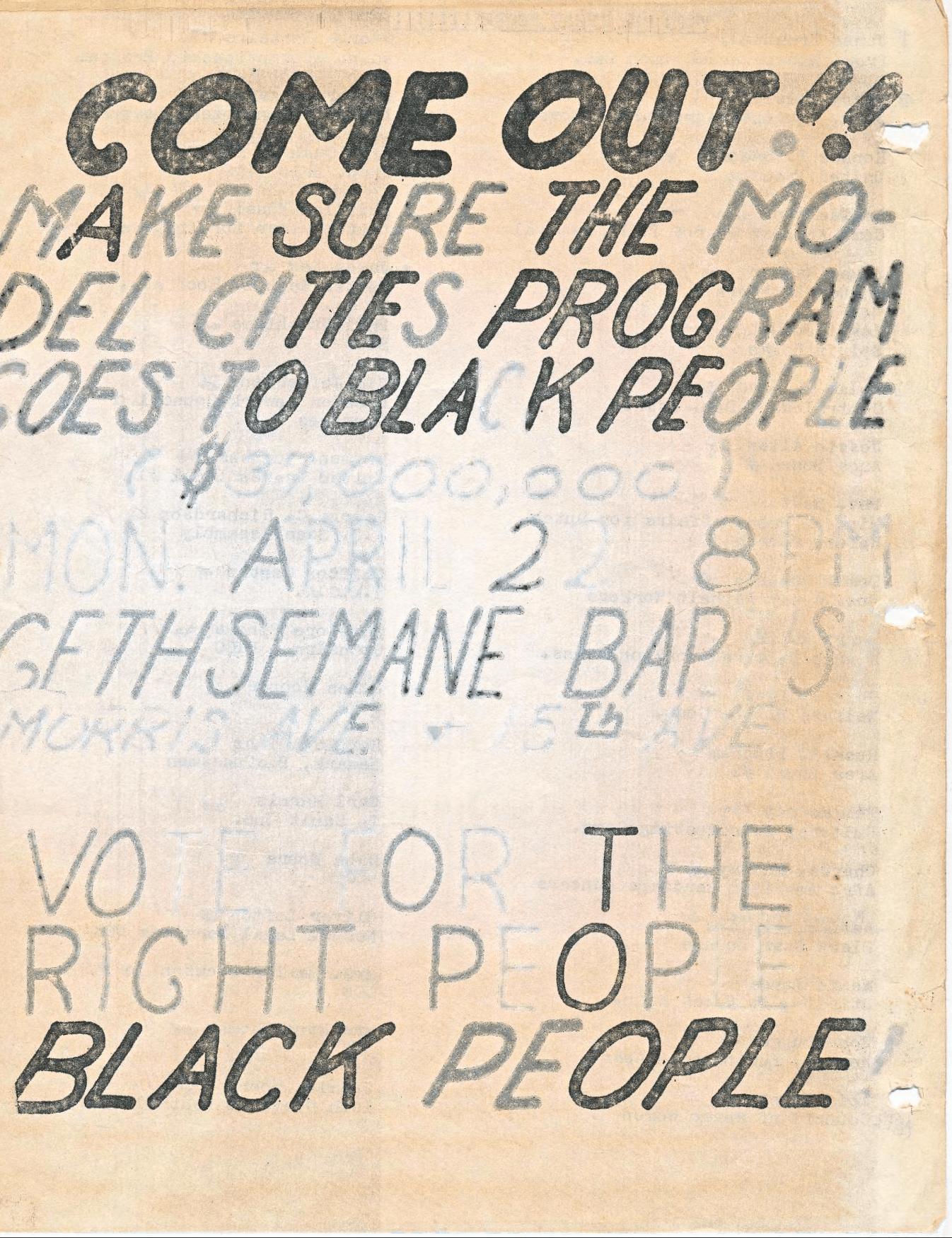

Flyer encouraging Newark community members to vote in the Model Cities Neighborhood Council election on April 22, 1968. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection