Junius Williams

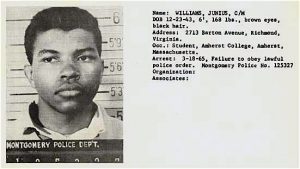

Junius Williams grew up in Richmond, Virginia before leaving to attend Amherst College in Massachusetts in 1961. While in Amherst, Williams became involved in the wave of campus activism that was sweeping the nation and, during breaks from classes, was involved in the national Civil Rights Movement. Williams participated in the March on Washington (1963), was involved with the Northern Student Movement (1964), and was arrested in Montgomery, Alabama during the Selma-to-Montgomery March in 1965. During his senior year at Amherst College in 1965, Williams was recruited by Tom Hayden, a leader of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), to come to Newark and work with the SDS-sponsored Newark Community Union Project (NCUP).

Upon his arrival in Newark, Williams immediately became involved in organizing the city’s poor and working-class Black communities around issues in housing, police brutality, and employment. Williams and other NCUP members went door-to-door in the Central Ward to ‘get people to overcome their fears and go on eventually to become their own community organizers and leaders.’ While working for NCUP, Williams also attended law school at Yale University and worked at Essex-Newark Legal Services Project. When the War on Poverty came to Newark, Williams became involved in the city’s anti-poverty agency, the United Community Corporation (UCC) as well.

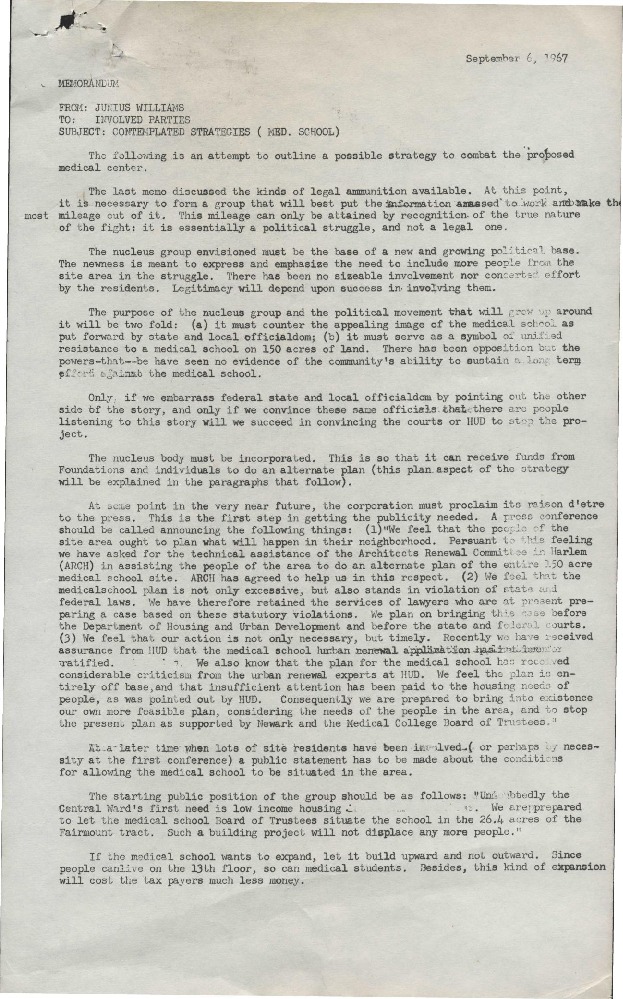

In 1967, Williams joined in the fight to prevent the College of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey from taking nearly 200 acres of land in the Central Ward and displacing 20,000 Black and Puerto Rican residents. During the rebellion in July of 1967, Williams directed a team of law students in the VISTA program in interviewing witnesses of violence inflicted by police and National Guardsmen and prepared sworn affidavits for the Essex-Newark Legal Services Project.

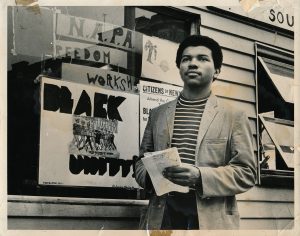

After the rebellion, Williams and Phil Hutchings of SNCC formed the Newark Area Planning Association (NAPA) to continue the fight against the medical school. Williams utilized his connections with regional planning and architecture students at Yale to develop an alternate plan for the medical school. With the alternate plan in hand and support from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, NAPA and the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal opened a new chapter in the fight against the Medical School land grab. Williams became co-chairman of the Negotiating Team with Harry Wheeler to successfully negotiate an agreement with city, state, and federal officials that reduced the original acreage, guaranteed low-income housing construction, and mandated job training and hiring for the city’s Black and Puerto Rican populations in the school’s construction.

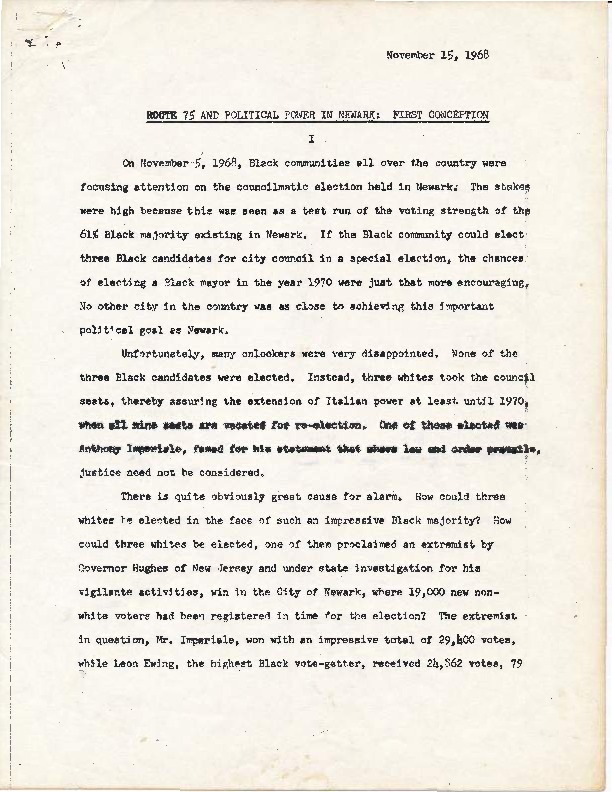

In addition to his work with NAPA, Williams also directed the Newark Housing Council, which was created to coordinate the development of more than 1,000 units of low-income housing on land coming from the Medical School Agreements. Williams was also a member of the United Brothers (1968) and took part in the Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention (1969) to support Ken Gibson’s 1970 mayoral election. Under the Gibson administration, Williams became the youngest director of the Model Cities and Community Development Administration in the nation at the age of 26.

Williams went on to become the youngest president of the National Bar Association, the oldest and largest organization of Black attorneys in the nation. He has held many notable positions in Newark, where he is currently the chairman of Newark Celebration 350, the organization that has planned and financed more than 200 activities to celebrate the 350th anniversary of the city’s founding.

Reflecting on Williams’ contributions in Newark, Tom Hayden later wrote, “If he had come along forty years later, he might have been Barack Obama. But instead he became one of those gifted young black leaders who invested their lives in creating the conditions for Obama’s future.”

References:

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

Junius Williams describes how he was recruited by Tom Hayden to come to Newark in 1965. — Credit: Robert Curvin Collection

Memo from Junius Williams outlining possible strategies to combat the proposed Medical School in the Central Ward. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Junius Williams explains the political significance of the Medical School Fight for Newark’s Black communities. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Paper written by Junius Williams explaining the political implications of the planned Route 75 construction on the 1970 mayoral election. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection