Community Control of Schools in Newark

With the emergence of the Black Power Movement in the mid-1960s, many Black communities in the urban north had moved away from integration as their key educational goal to the community control of schools in Black neighborhoods. By 1970, Newark had become a majority-black city and its school population was 73% black and 9% Latino. However, administrators and teachers in the Newark Public Schools remained disproportionately white. Informed by calls for self-determination raised by the Black Power Movement, struggles for community control of schools aimed to give black communities control over curriculum, policies, spending, and hiring in schools in their neighborhoods. “The drive for community control in Newark,”wrote Newark education advocate Helen Means, “is an integral part of an attempt on the part of black people to control their community.”

These struggles for community-control of schools had two main thrusts in Newark: 1) working to take control of the Newark Public School system; 2) building independent, African-centered schools.

Calls for the community-control of schools in Newark were influenced by the city’s Black Power Movement, as well as intense struggles in Brooklyn’s Ocean Hill-Brownsville neighborhood. Like the teachers strikes in Newark, the strike in 1968 in Ocean Hill-Brownsville pitted labor rights against the Black Freedom Movement. A historically Jewish community, by the 1960s, Ocean Hill-Brownsville was primarily composed of poor and working-class black and Puerto Rican people. Enabled by New York’s experiment in the decentralization of school oversight, the Ocean Hill-Brownsville neighborhood in Brooklyn was able to gain local control of its schools. Already facing open critiques of its supposed support of black militants and its curriculum, when the newly formed school district requested the transfer of several teachers and administrators, the teachers union challenged the action, which eventually led to citywide strikes. All of the teachers and administrators whom the district believed to be unsupportive of the changes in curriculum made by the community were white. Intensified by claims of racism and antisemitism, the fight between the community and the United Federation of Teachers mostly ended the movement for community control of schools in New York City.

In Newark, the struggle for community-control of schools was led by the Organization of Negro Educators (ONE). “We realized that the improvement of education in the city was tied to the improvement of other elements in the city that had to include the input of city people,” ONE president Fred Means later recalled. Organizers from ONE met frequently with parents, teachers, and leaders in struggles for community-control like Preston Wilcox and Rhody McCoy to build community power in Newark. In March 1969, ONE held a workshop on “Moving to Community Control,” which resulted in a list of 25 resolutions for achieving community control of schools in Newark. One of the major themes among the resolutions was empowering parents and community leaders to play active roles within schools, educational institutions, and policy-making. ONE also advocated for Black teachers and administrators in schools, winning several battles to promote Black teachers from substitutes to regular teachers. That December, ONE Vice President Eugene Campbell was appointed principal of the Robert Treat School after a successful community-led struggle to replace the school’s white administrators.

The Committee For Unified Newark played a central role in establishing community-controlled African-centered schools. In 1967, Amina Baraka formed the Afrikan Free School (AFS), which became one of the most prominent examples of community-controlled education. The idea for the AFS started when Baraka and other women associated with the Spirit House noticed that black children who attended their cultural arts classes and events could not read. Many of these children attended Robert Treat Elementary School, where students’ test scores were three years behind the national average. In response, these women started a study group to teach students to read using black nationalist principles. For example, they used flashcards to teach the ABCs where each letter linked to a term associated with the Black Freedom Movement.

From these foundations grew a movement for African-centered schools. In 1969, The NewArk School and the Chad School were formed as community-based alternatives to NPS. In 1970, Baraka was awarded a federal grant that provided the means to start an experimental classroom at Robert Treat and thereby institutionalize the Afrikan Free School. Serving students from a range of grade levels, the curriculum of the classroom included a mix of traditional subjects as well as African folklore and languages. In addition to changing curricula, activists also pushed to rename schools to reflect the history and culture of Newark’s majority-black population. In July 1971, United Community Corporation president and CFUN member David Barrett successfully petitioned the Board of Education to rename the Robert Treat School the Marcus Garvey School. The renaming of schools symbolized one of the key goals of the community-control of schools, “to help children establish positive images of themselves” through understanding black history and achievements.

Ultimately, community-control of schools was part of a broader push for black self-determination. Calling for principals who understood the cultural and emotional needs of schools’ most marginalized students and for curriculum relevant to black communities, calls for community-control focused on providing students with positive images of themselves and preparing students to contribute to the liberation of black people. However, the two key issues that drove calls for community-control–the failure to desegregate schools and to adequately educate black and brown students–remain critical issues in current battles for equitable public education.

References:

Tom Adam Davies, Mainstreaming Black Power, University of California Press, 2017.

Jerald E. Podair, The Strike That Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis, Yale University Press, 2002.

Russell John Rickford, We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination, Oxford Press, 2016.

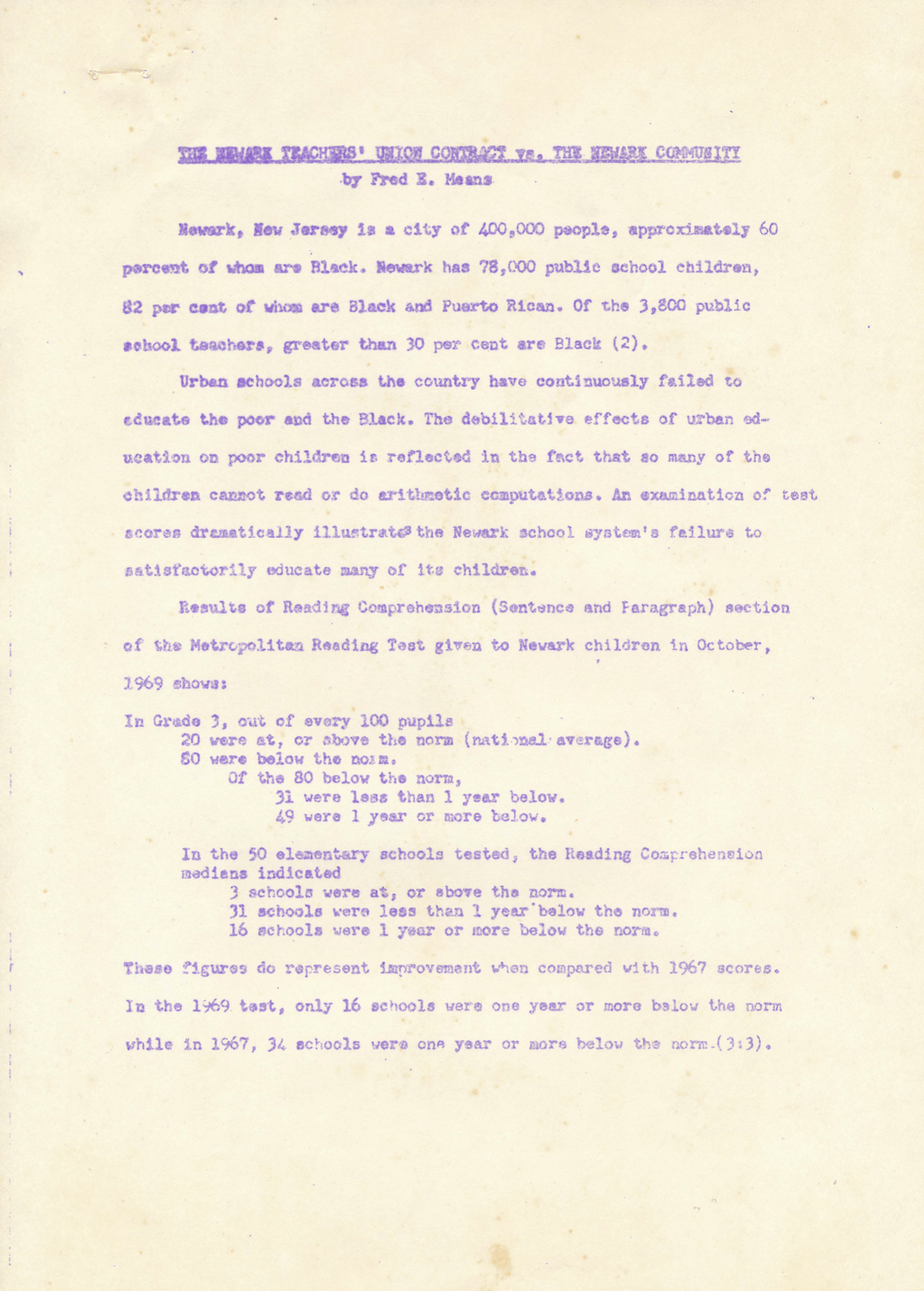

Paper written by Helen P. Means, a teacher in Newark Public Schools and wife of Fred Means. The paper discusses the movement for community control of education in black communities, particularly in Newark, NJ. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Summary of Resolutions Developed at a workshop on “Moving To Community Control,” hosted by the Organization of Negro Educators on March 21, 1969. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Pat Green, co-founder of the Chad School, discusses the struggle for community-controlled schools and the founding of the Chad School in 1970. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

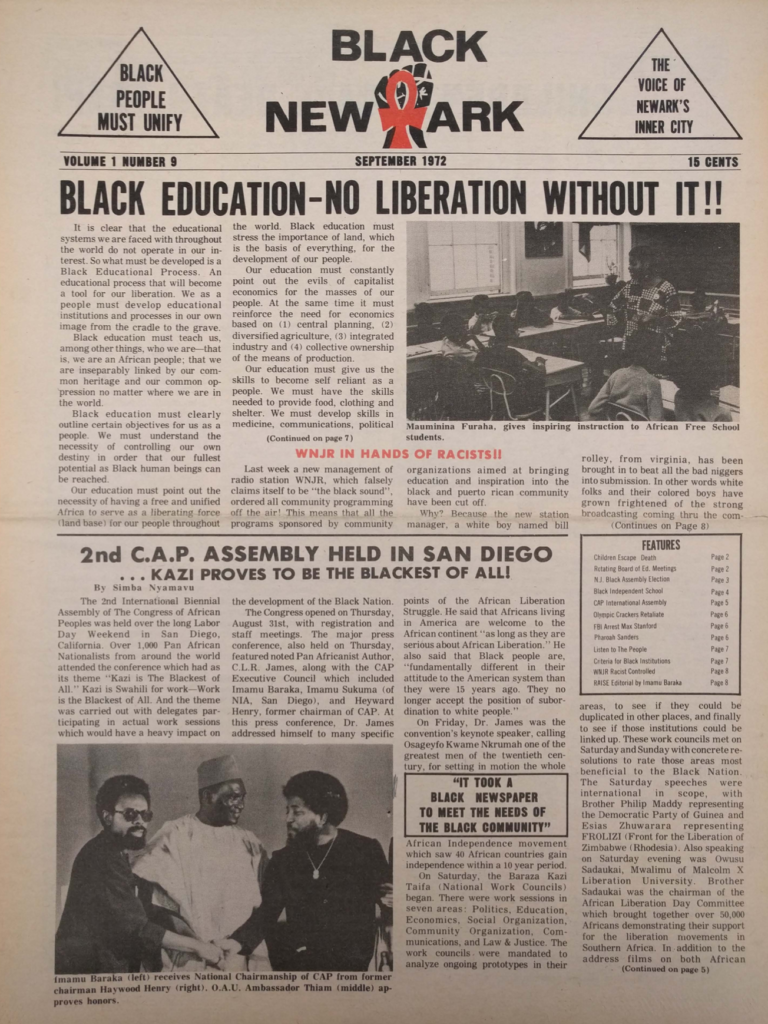

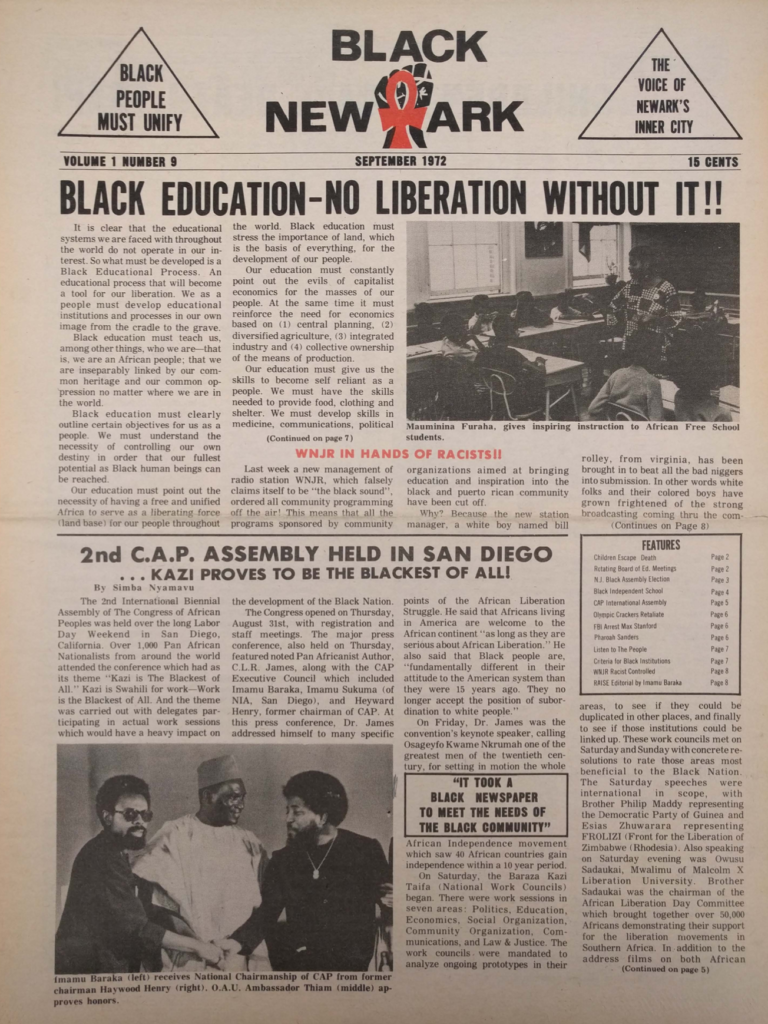

Issue of Black New Ark, a local newspaper of the Committee for a Unified Newark (CFUN). The issue includes coverage of the African Free School, The NewArk School, and the Chad School. –Credit: NYU Tamiment Library

Explore The Archives

“The Meaning of Community Control” by Preston Wilcox, 1969. Wilcox was a leader of the movement for community control of schools in Harlem (IS 201) and Ocean Hill-Brownsville in the late 1960s. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

“Social Conflict: Teachers’ Strikes in Newark, 1964-1971,” by William M. Phillips, Jr. and Joseph M. Conforti. This 1972 report includes a detailed timeline of community-led struggles around education in the years, months, and days leading up to the Newark Teachers Strikes. –Credit: Newark Public Library

In this email exchange, Fred Means, the founder of the Organization of Negro Educators (ONE), discusses the formation of ONE and its vision for the education of black and brown students. –Credit: Newark Public Library

A leaflet distributed by the Organization of Negro Educators, from 1968. The leaflet includes newspaper coverage of ONE’s recent activities. –Credit: Newark Public Library

An edition of “News One,” the official newsletter of the Organization of Negro Educators, from June 1969. The newsletter includes a message from President Fred Means and updates of ONE’s recent activities. –Credit: Newark Public Library

A newsletter from the Committee For Unified Newark, titled “Unity in the Community,” from November 1969. The newsletter describes the successful campaign to oust of the white administration of the Robert Treat School. –Credit: Columbia University Libraries

A proposal created by the Committee For Unified Newark (CFUN) for funds to create an “Experimental College” in Newark. The purpose of the Experimental College was to provide Black students from elementary school through college with “supplemental cultural education.” –Credit: Columbia University Libraries

“South Side High School: The Personification of a Black Future,” a speech given by Fred Means at the graduation ceremonies of South Side High School (now Malcolm X Shabazz) on June 28, 1971. In his speech, Means discusses the importance of educaiton in struggles for Black liberation and offers insights into the state of education in Newark. –Credit: Newark Public Library

“The View From This Side of the Microphone,” a statement made by Fred Means at a meeting of the Newark Board of Education on March 26, 1974. In the statement, Means expresses his frustration with other board members during his time on the BOE. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Transcript of an oral history interview with Eugene Campbell from May 13, 1985. Campbell discusses his career in education, becoming principal of Marcus Garvey School and some of the African-centered programs that were run there. –Credit: Komozi Woodard

Pat Green, co-founder of the Chad School, discusses student walk-outs to protest racist violence in Newark in 1968. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Pat Green, co-founder of the Chad School, discusses the Black Youth Organization in Newark in the late 1960s-early 1970s. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

TThe Newark Teachers Strikes

The Strike in 1970

As African Americans flowed into Newark during the Great Migration, the Newark School Board embraced a de facto racial segregation system built on patterns of residential segregation. This system kept white students out of majority African American schools and black students out of white neighborhoods. Discriminatory hiring practices also excluded African Americans from teaching, especially on the secondary level, and many white teachers were less enthusiastic about teaching black students, deeming them to be less capable than their white peers.

Thus, as African Americans formed an increasingly large share of the population of the city, their status as second-class citizens within the school district was cemented. Consequently, in the aftermath of the 1967 rebellion, the public-school system, like other sites of racial discrimination, became a target of efforts to create structural and systemic change. For segments of the African American community, any attempt to create change in the school district needed to challenge racial segregation, discriminatory hiring practices, and curricula that perpetuated white supremacy. Alternatively, for many of the teachers who joined the Newark Teachers Union (NTU), their mission to create change in the school district centered on teacher empowerment. Already opposed in some ways, these factions came into direct opposition over ideas of race, class, and social justice when the NTU led strikes in 1970 and 1971.

Founded in 1936, the NTU initially embraced leftist principles and practices. Unlike the Newark Teachers Association, the only organization for Newark teachers before the founding of the Union, the NTU called for gender and race equality, excluded administrators, and challenged administrative policies to protect their interests. However, by the time the city imploded in the aftermath of the 1967 rebellion, the political positioning of the NTU had shifted from a leftist labor organization to an organization that represented the mostly white teaching professionals on the front lines of one of the city’s most racialized institutions. Highlighting this shift was the fact that in their public discussions of the strike in 1970, the NTU centered issues of power and class over race. Therefore, while Carol Graves, an African American woman, served as the president and face of NTU, the educational experiences of black and brown students did not seem to be among the key goals of its strike. However, whereas the NTU’s public positions of the strike focused on power and class, their fear of black political power certainly figured into its position as many in the city anticipated the election of a black mayor in the 1970 municipal elections.

During the first week of the strike in 1970, 75% of teachers participated, and it brought a halt to the normal operations of the school district. Many members of the African American community believed the stoppage was having a disproportionately negative effect on black and brown students. Wanting to bring the strike to an end, Mayor Hugh Addonizio questioned the board’s plan to break the union by arresting officers and leaders, and instead called for an end to the strike. The strike ended after 23 days with the board and the union agreeing to a one-year contract. The agreement included a decreased class sizes and an increase in salary. When the one-year contract came to an end in 1971, the NTU again led a strike demanding the right to binding arbitration and release from board-mandated nonprofessional chores.

The Strike in 1971

The 1971 strike took place on different political terrain after the city’s Black Power Movement had succeeded in electing Ken Gibson as Newark’s first black Mayor the year prior. Additionally, while the NTU was poised and ready to do battle to solidify the gains they achieved in 1970, an awakened populace now saw the NTU as the enemy because of some of its demands and its allies. These looming tensions between the union and the African American community were reignited when the NTU once again went on strike in 1971.

These tensions were amplified when Newark’s newly-elected mayor, Kenneth Gibson, made appointments to the school board in 1970, giving nonwhites the majority. These appointments included Jesse Jacob, who openly opposed the Union and served as the president of the school board during the 1971 strike. They also included Charles Bell, who had loyalties to both unionism and black activism. Furthermore, although the Newark Student Federation, an organization of high school students headed by student activist Larry Hamm, stayed neutral in the previous strike, they sided with the New Ark Community Coalition during the 1971 strike.

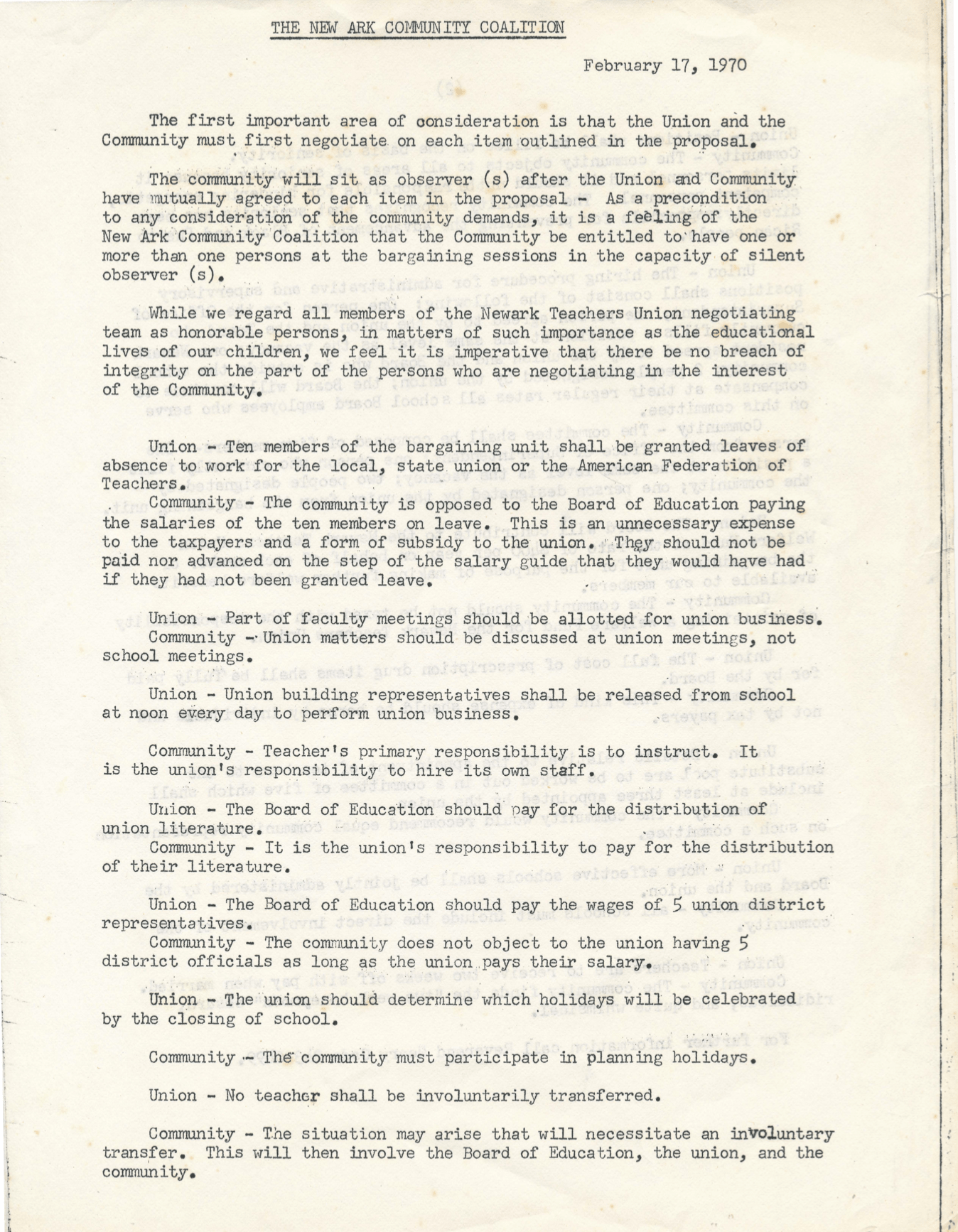

The New Ark Community Coalition saw itself as the voice of the African American community, and was composed of numerous community organizations, including the Organization of Negro Educators (ONE), the Committee for a Unified NewArk (CFUN), the Young Lords, and the Black Organization of Students (BOS) among others. Detailing the main contention of the New Ark Community Coalition, Fred Means, former Chairman of the Newark-Essex chapter Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and one of the founders of ONE, argued that the strike was not about improving education in Newark. Instead, he argued that the strike was about money and power, as many had seen in the 1968 Ocean Hill-Brownsville strike in nearby New York City. Alongside the other member organizations of the New Ark Community Coalition, ONE called for the community to play a role in contract negotiations between the board to ensure parents had a voice in shaping the new contract and to increase community-control of schools.

Moreover, race, class, and gender politics further complicated the debates around the strikes. Anthony Imperiale, the infamous North Ward vigilante, who was openly racist and embraced violent tactics, spoke out in support of the strike. His support further fanned the tensions between the African American community and the NTU. Additionally, while some African American teachers supported the strike, most notably Carole Graves, their support of the strike did not help their standing in the African American community. Historically seen as part of the black middle-class and social elite, African Americans tended not to view African American teachers as working-class laborers protesting the control of management. Furthermore, gender politics undoubtedly influenced the rhetoric around teacher empowerment, a job mostly gendered female, but seemed to be beyond much of the mainstream debates around the strikes. Undoubtedly, though, gender politics was shaping people’s perception. Historically, the NTU leadership was white and male; Carole Graves was the exception.

After more than two months of strikes, counter-protests, and violent attacks on striking teachers and community advocates, Mayor Gibson enlisted the support of veteran organizer Clarence Coggins to put together a strategy for settling the strike. While Coggins, who was in charge of the Model Cities community advisory board, worked to bring the many factions to the table, Gibson finally explicitly called for peace with his statement “A Call for Reason.” While negotiations were underway, Larry Hamm and the Newark Student Federation led a mass walk-out and march from Arts High to downtown to demand a seat at the table and an end to the strike. The initiative gained community support and led leaders of key opposing factions, including the Board of Education, to call for an end to the strike. On April 18, 1971, after eleven long weeks, the longest strike in a major American city at the time came to an end. The NTU was able to win the right to binding arbitration and the language around nonprofessional chores was removed from the contracts of teachers.

While the strike came to an end in April of 1971, the fissures it created continued. Many teachers who had participated in the strike never returned to the school they previously taught in, the faculty of schools continued to be divided based on the sides they chose during the strike, and countless teachers dealt with the lasting effects of being arrested, including Carol Graves. Furthermore, the Mayor, the New Ark Community Coalition, the NTU, the Newark Student Federation, and the Board of Education, never came together to define a plan for the improvement of the school district. However, Larry Hamm was appointed to the Board of Education by Mayor Gibson as the youngest school board appointee in the country and Fred Means was appointed to the school board in 1974.

Striking teachers had challenged the traditional set of rules, at a moment when the ideals of law and order were becoming more critical to cultural politics and when African Americans were gaining more control of city politics in Newark. The Governor of New Jersey at the time, William Cahill, called out the striking teachers for encouraging students to challenge the laws of the state and nation. Missing from his statement was an acknowledgment of the role student activism, particularly around the issue of racial equality, had already played in changing the face of politics in Newark. Nonetheless, racial segregation and inequitable school funding continue to play a leading role in shaping inequitable educational outcomes into the present.

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation, Rutgers University Press, 2014.

Steve Golin, The Newark Teacher Strikes: Hopes on the Line, Rutgers University Press, 2002.

Russell John Rickford, We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination, Oxford Press, 2016

Lois Weiner, “Class, Gender, And Race in The Newark Teacher Strikes,” New Politics, IX (2), 2003.

Clip from an interview with Fred Means, in which he discusses the Organization of Negro Educators (ONE) in the late 1960s-early 1970s. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

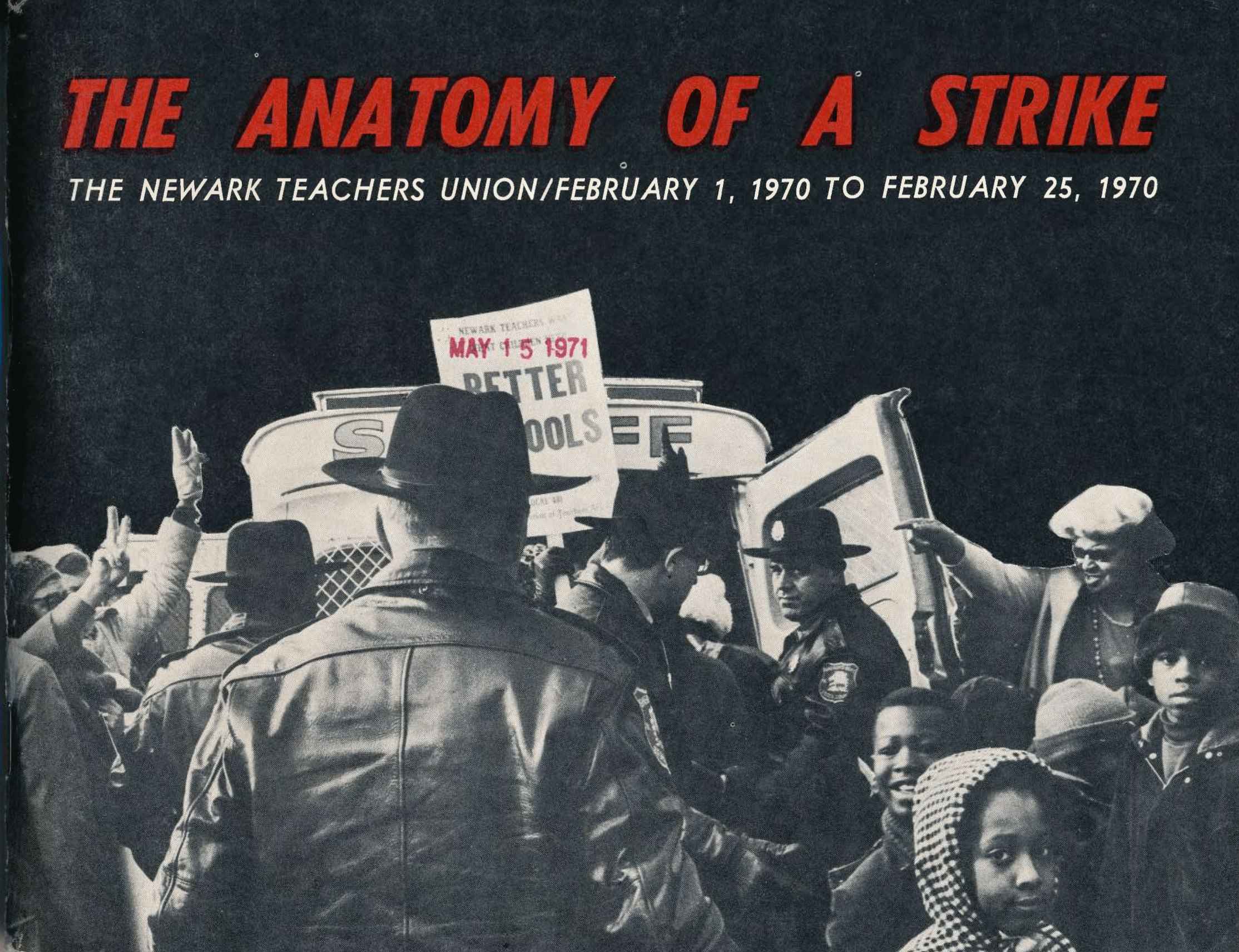

A report published in 1971 by the Newark Teachers Union, titled “The Anatomy of a Strike: The Newark Teachers Union/February 1, 1970 to February 25, 1970.” –Credit: Newark Public Library

Carol Graves, former president of the Newark Teachers Union, discusses the Newark Teachers Strikes of 1970 and 1971. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

A statement of the Newark Community Coaltion from February 17, 1970, outlining the Coalition’s positions on the Newark Teachers Strike. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Larry Hamm, chairman of the People’s Organization for Progress, describes student activism during the 1971 Newark Teachers Strike. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Former Newark Board of Education member Vickie Donaldson reflects upon her time on the Newark Board of Education and the outcomes of Newark Teachers Strikes. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Amina Baraka and Estelle David reflect on the Newark Teachers Strikes in 1970 and 1971. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Explore The Archives

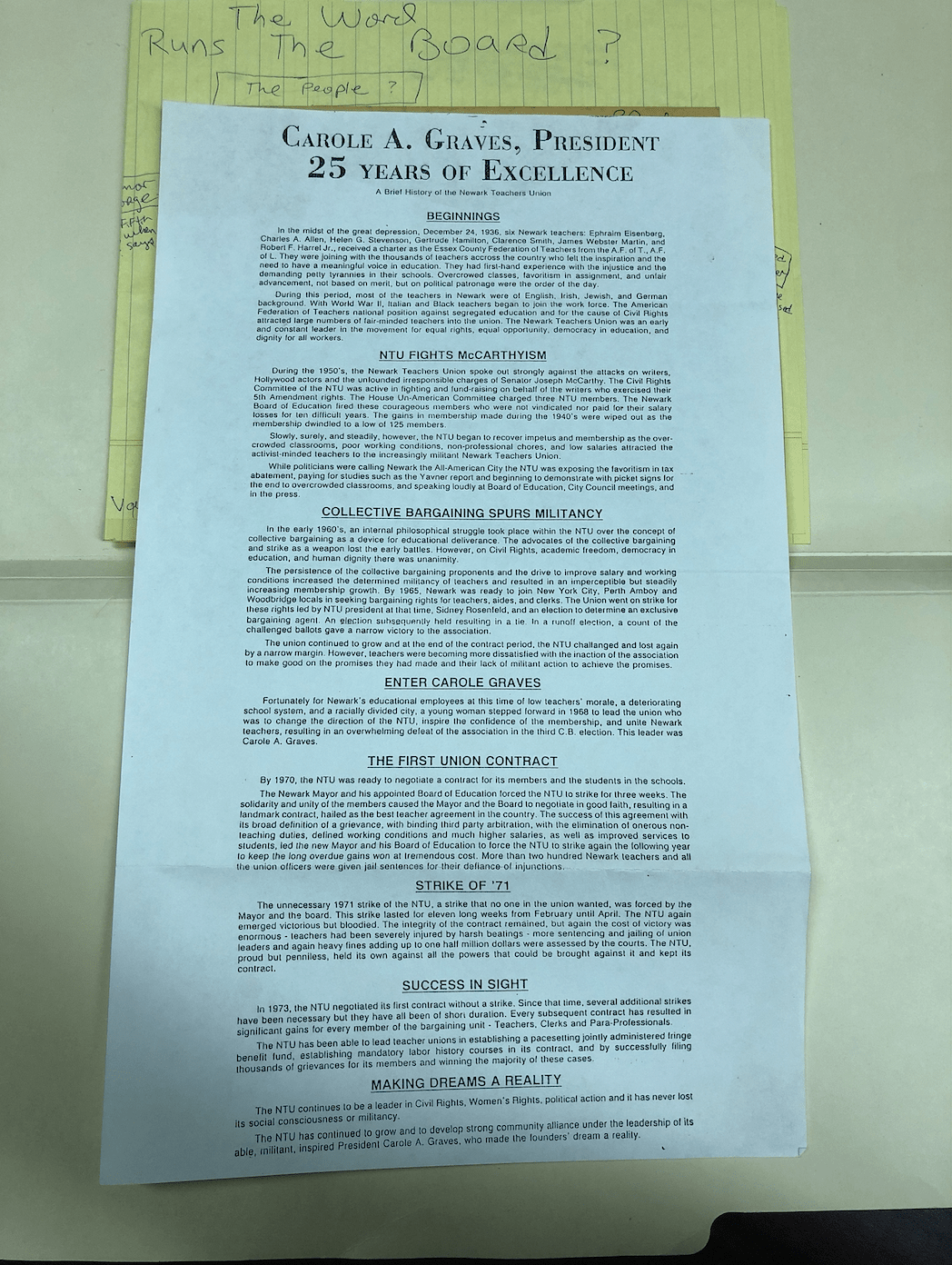

Documents detailing the career of Carole A. Graves, the President of the Newark Teachers Union during both strikes.

A February 26, 1970 article from the New York Times discussing the outcome of the 1970 strike. –Credit: New York Times

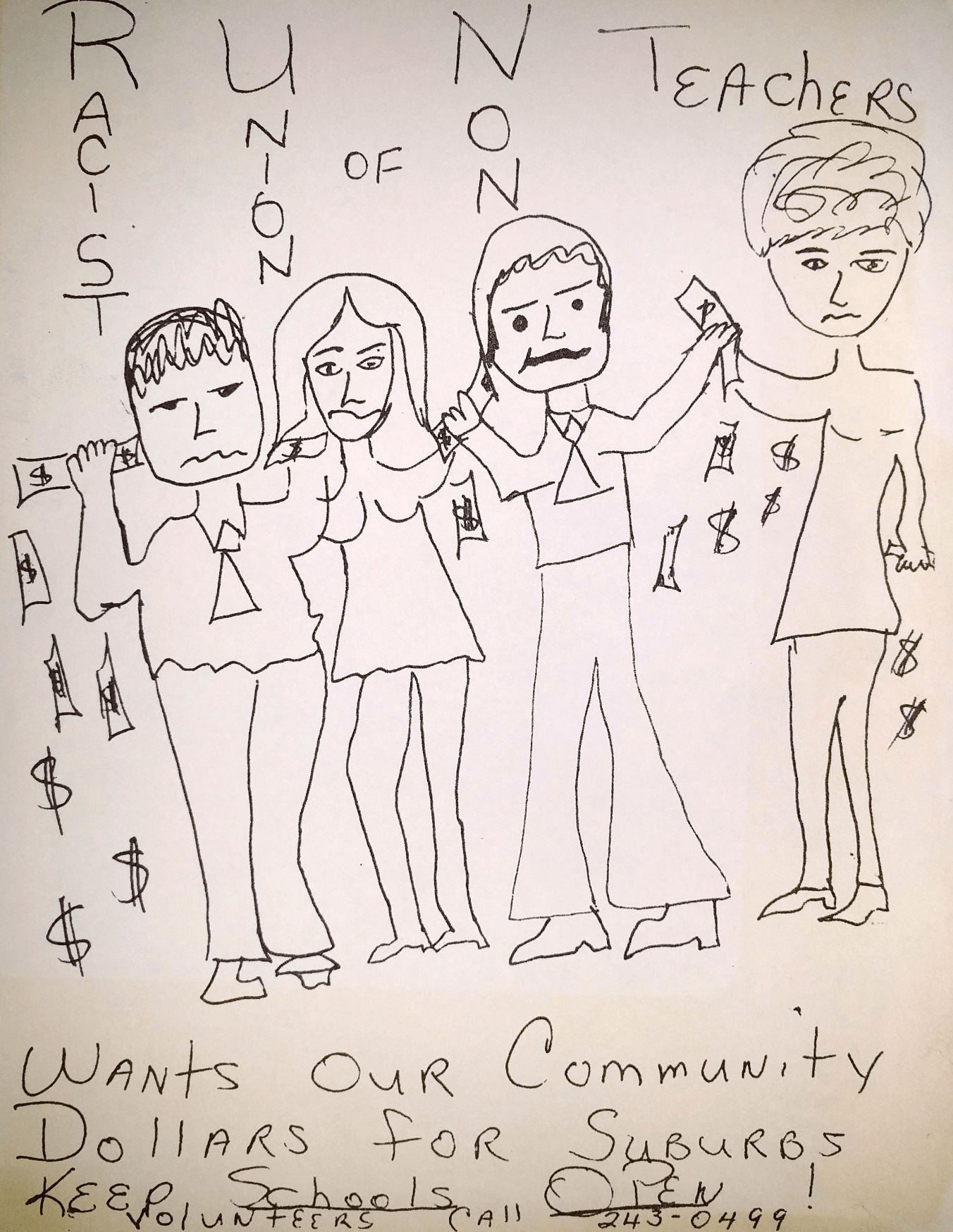

A flyer that depicts the Newark Teachers Union as racists, driven by money. The flyer was illustrative of community criticisms of the NTU during the 1970 and 1971 strikes. –Credit: Newark Public Library

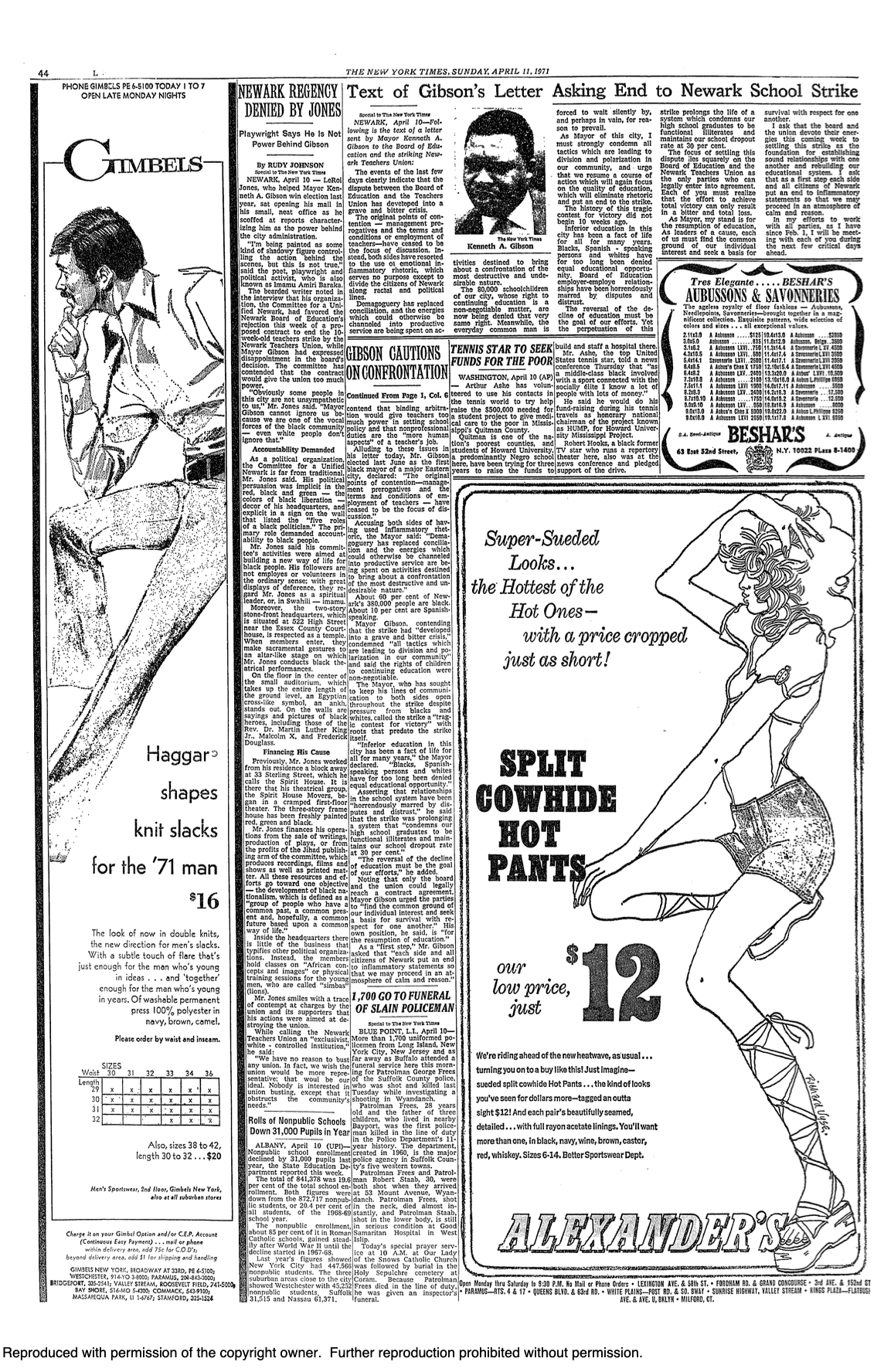

Coverage of Mayor Kenneth Gibson’s call to end the strike in the New York Times on April 11, 1971. –Credit: New York Times

Clip from an interview with Larry Hamm, in which he describes the demands of NPS students during the 1971 Teachers Strike. During the strike, Newark students held walkouts, mass rallies, sit-ins, and issued demands and negotiated with the Board of Education. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

Clip from a 2020 oral history interview with Vickie Donaldson, former member of the Newark Board of Education, in which she discusses gender inequality during the Gibson administration and efforts to uplift Black women educators and administrators during her time on the Board of Education. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Clip from an interview with Fred Means, in which describes his experience on the Newark Board of Education. A leading figure in the struggle for educational equality for African American students and teachers, Means was appointed to the Board of Education in 1973 by Newark’s first Black Mayor, Ken Gibson. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

Clip from a 2020 oral history interview with Rebecca “Becky” Doggett, former executive director of the Newark Pre-School Council, in which she discusses efforts by Amiri Baraka and the United Brothers to takeover the Newark Pre-School Council in the early 1970s. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Clip from an interview with Larry Hamm, in which he discusses his experience on the Newark Board of Education in the early 1970s. A leading organizer of Black high school students during the Newark Teachers Strike in 1971, Hamm was appointed to the Board of Education that year at only 17 years old. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

Clip from a 2020 oral history interview with Steve Block, former member of the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP), in which he discusses shortcomings in education policy during Ken Gibson’s Administration. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection