CULTURE OF POLITICAL ACTIVISM IN NEWARK

There is little evidence of a persistent culture of militancy in Newark, as set in motion by the National Negro Council (NNC) coming out of the Great Depression in the 1930s, and moving into the War Years of the 1940s. Or with the confrontations waged by the Congress of Racial Equality from the days of its formation by George Hauser and James Farmer in Chicago. A CORE chapter was not organized in Newark until 1960. Hints of the collective political personality of African Americans in Newark are found in comments by Garveyites as far back as 1922 at their national convention, when they criticized the African American community in Newark for “its lack of political motivation, accomodationist attitudes and preference for the pleasures of nightlife”.

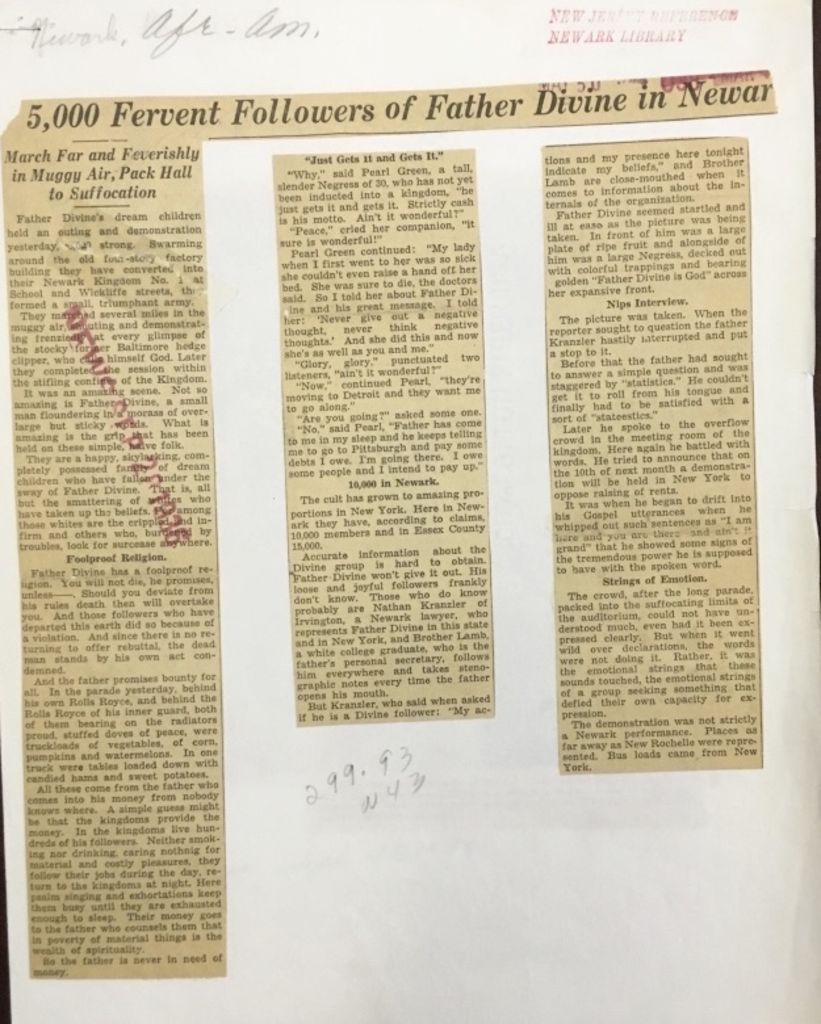

The Garvey organization had no more than 100 members at the time of that report, while Father Divine and Noble Drew Ali boasted hundreds of members. The latter two organizations supported self help, and thus their large and pageant filled displays of popularity were never demands for equal rights, and never seen as threatening to the white power structure.

Perhaps Black Newark was accommodating to segregation since their neighborhoods were so “institutionally rich.” They had churches, social clubs, fraternal organizations, businesses and nightclubs. “The Barbary Coast” was the nickname given to the Lincoln Park area in the 1920s and ‘30s because of the strip of black businesses, jazz clubs and booming nightlife, located at the eastern end of the Third Ward where African Americans lived with Jews, and Italians.

“The resulting insularity of black organizations led to the neglect of popular mobilizations against social injustice and perhaps even encouraged its own kind of accommodation.” Put another way, maybe segregation wasn’t so bad when you have what you want in the neighborhood, right down the street, or just around the corner?

But segregation took its toll on the people. William Ashby, of the Newark Urban League, spoke for his fellow veterans. “They said, ‘I’m tired of all this goddamn crap. Tired of hearing the white man say, ‘I can serve no niggers in my restaurant,’ tired of being told, ‘I ain’t got no place for colored in my hotel.’ Well hell, I’ve been to Europe. Hitler leveled his bullets at me. Missed. I went to the Pacific. Mr. Hirohito sent his madmen to blow me to hell in their planes. I’m still here. Why don’t I tell the white man, ‘take your goddamn boots off my neck!”

————

Tired of hearing the white man say, ‘I can serve no niggers in my restaurant,’ tired of being told, ‘I ain’t got no place for colored in my hotel.’

————

Individuals and small groups challenged the power of northern Jim Crow.

Throughout the 1940s, African Americans used the Black Press to denounce denial of access, and the courts to fight discrimination. The NAACP youth organization became active in challenging segregation. The singer Lena Horne filed suit and won $500.00 damages against Caruso’s restaurant in North Newark for refusing to seat her racially mixed party. The New Jersey legislature, led by Essex Assemblyman Frank Hargreaves, set up the Division Against Discrimination in 1942 to investigate grievances against public accommodations. In the early 1940s, Prosper Brewer, Republican Chairman of the Third Ward (who had earlier led a longshoremen strike for better wages), threatened a boycott of Jewish business to protest the failure of city officials to grant a liquor license to black tavern owners. And Herb Tate, Sr., convinced Grace Freemon of the NJ State Legislature to consider and pass legislature that made segregation in public accommodations illegal in New Jersey in 1949.

Even though the most blatant Jim Crow practices ended shortly after World War II, the covert decision making that ignored black rights continued, despite lip service by officials to the contrary. Segregation in public housing; massive housing code violations by absentee white landlords; frequent cases of police brutality; discrimination at the city hospital; and hiring in the public sector all continued to plague the city’s black populations.

By the 1950s, the black migrant population overwhelmed its confinement to the Old Third Ward, and nearby areas. In less than a decade the black population doubled, from 74,000 to 142,600, while the white population declined by almost 100,000 from 348,856 to 255,800. Though the African American middle class increased in both size and influence after the war, many chose to move to nearby East Orange, Orange, and Montclair—suburbs increasingly open to black homeownership.

————

By the 1950s, the black migrant population overwhelmed its confinement to the Old Third Ward, and nearby areas.

————

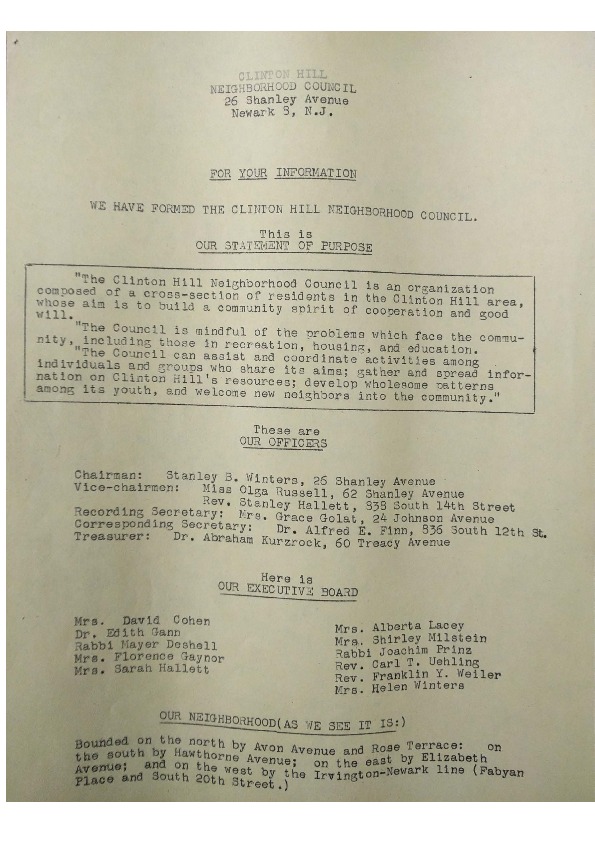

The Clinton Hill Neighborhood Council (CHNC) fought against urban renewal and for fair and equal municipal services for homeowners in the Clinton Hill section of Newark. To broaden and deepen their neighborhood impact, the CHNC would later invite the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) to join them in the early 1960s. This partnership did not survive.

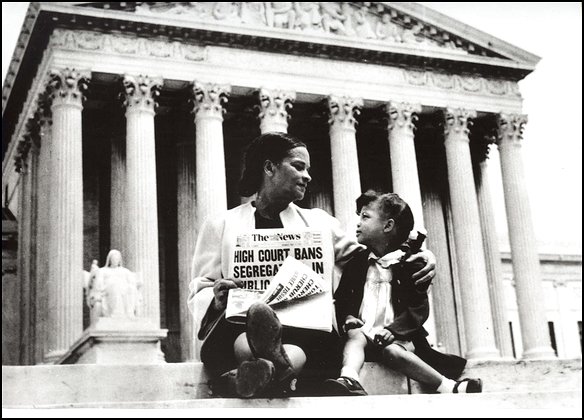

National events helped shape the course of Black perspectives on race. The Supreme Court ruled segregated schools to be illegal in the class cases of Brown vs. Board, et al. in 1954. Organizations like the Montgomery Improvement Association set a new tone and gave strategic direction to a new crew of freedom fighters, mostly young, who took on the battle against Jim Crow in the South, beginning with the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955. Newark African Americans watched from afar, and were inspired by what they saw.

A view of the National Theatre on Belmont Avenue in Newark. The National Theatre was an important institution of leisure and entertainment for Newark’s Black communities. — Credit: WPA Photographs, NJ State Archives

Clip from an interview with Calvin West, Newark’s first African American Councilman-At-Large, in which he describes his experiences with segregation and racism while growing up in Newark. Mr. West describes the wealth of African American institutions in the city, but also the discrimination faced by Newark’s Black residents in the 1950s.

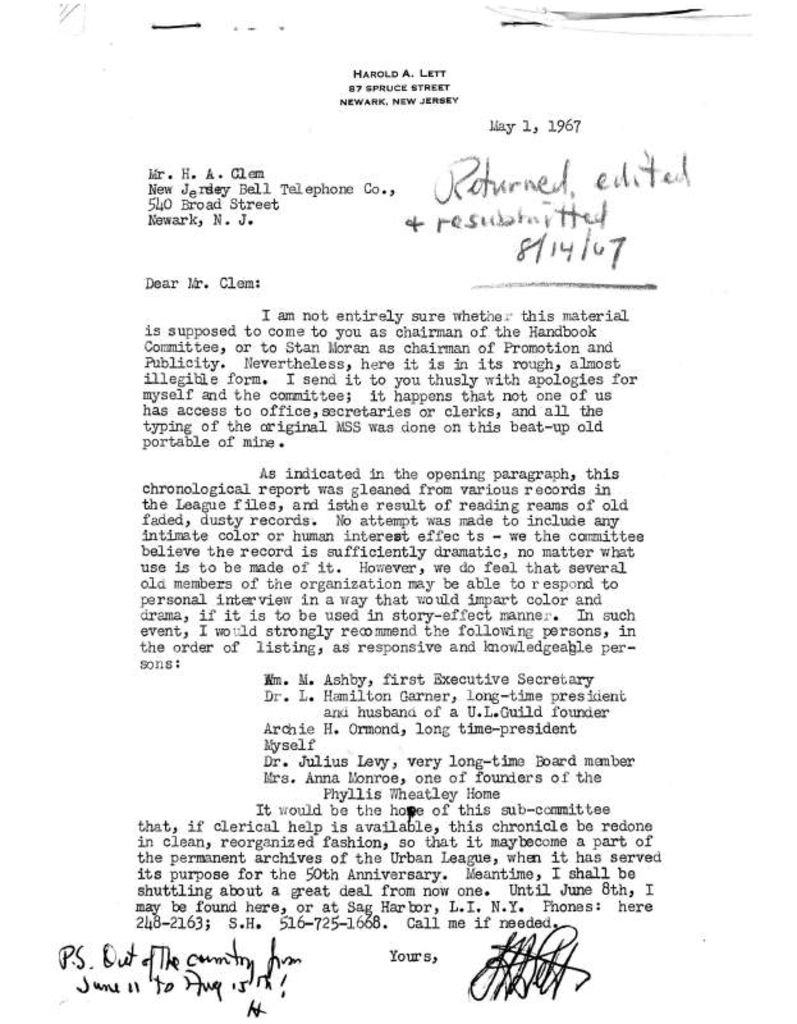

A detailed chronology of the activities of the Essex County Urban League from 1917-1952. The Urban League was one of the most active and influential organizations advocating for African Americans in Newark in the early 1900s. — Credit: Newark Public Library

A look inside the office of the Urban League at 58 West Market Street in Newark, which was purchased in 1918. The Urban League was one of the most active and influential organizations advocating for African Americans in Newark in the early 1900s. — Credit: WPA Photographs, NJ State Archives

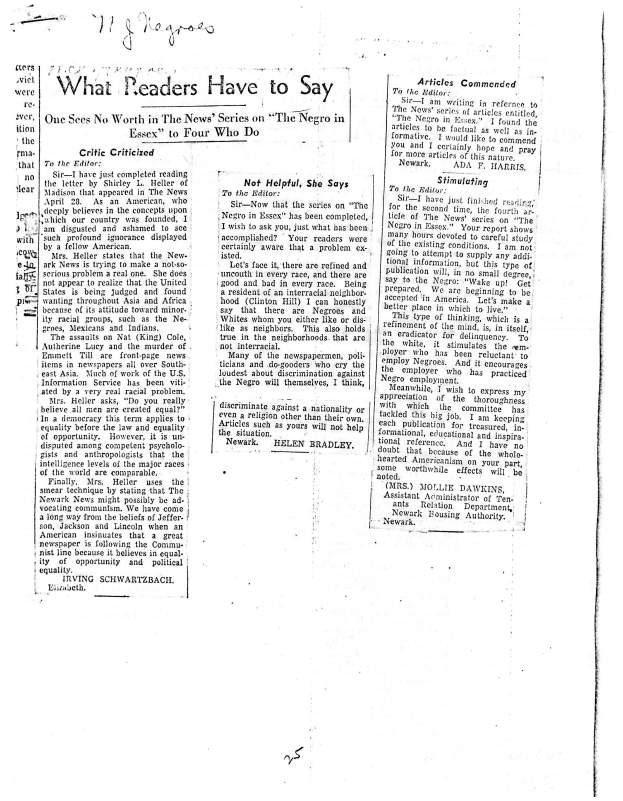

A series of articles from the Newark Evening News in 1956 titled “The Negro in Essex.” The series of articles drew upon the results of a survey the paper conducted in an attempt to call attention to issues of discrimination, segregation, and inequality faced by Newark’s African American communities. — Credit: Newark Public Library

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Robert Hill, ed. The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, Volume V

Barbara J. Kukla, Swing City: Newark Nightlife, 1925-50

Kevin Mumford, Newark: A History of Race, Rights, and Riots in America

Thomas Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North

Explore The Archives

Photograph of a congregation on the steps of the Moorish Science Temple in Newark in 1928. — Credit: Newark, NJ Memories Facebook Page

Article from the Newark Evening News in 1936 covering a demonstration attended by 5,000 followers of Father Divine in Newark. — Credit: Newark Public Library

View of a storefront church in Newark. Countless storefront churches popped up in northern cities in the 20th century as African American populations left the South during the Great Migrations. — Credit: WPA Photographs, NJ State Archives

African American teenagers dance inside Newark’s Skateland dance hall. Newark’s “Barbary Coast” was known for its jazz clubs and booming nightlife in the 1940s-1950s. — Credit: WPA Photographs, NJ State Archives

Letter distributed by the newly formed Clinton Hill Neighborhood Council (CHNC) to inform neighborhood residents of their purpose and officers. The CHNC fought against urban renewal and for fair and equal municipal services for homeowners in the Clinton Hill section of Newark. — Credit: Newark Public Library

“Neighborhood News” was the newsletter of the Clinton Hill Neighborhood Council (CHNC), formed in the early 1950s. The CHNC fought against urban renewal and for fair and equal municipal services for homeowners in the Clinton Hill section of Newark. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Mother (Nettie Hunt) and daughter (Nickie) sit on steps of the Supreme Court building on May 18, 1954, the day following the Court’s historic decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Nettie is holding a newspaper with the headline “High Court Bans Segregation in Public Schools.” — Credit: www.brownat50.org