Larrie West Stalks

Larrie West Stalks graduated from South Side High School in 1942 and went on to work as a union aide and secretary at Western Electric, and as a secretary at Local 1286 (IUE). In 1946, Stalks began to “literally work her way up from the basement of City Hall” when she started working as a clerk typist for the city government. While working in the basement of City Hall, Stalks held a second job working as district secretary for Congressman (and eventual Mayor) Hugh Addonizio. While working for City Hall and Rep. Addonizio, Stalks became “a young and ardent voice for black participation in politics.”

In 1950, Stalks led protests against the Far Eastern Restaurant, a downtown Chinese restaurant, for refusing to serve African American customers. Shortly after the protests, Stalks and Charles Matthews became the first African American customers served at the restaurant.

When Addonizio ran for Mayor in the 1962 election, Stalks helped to build a coalition of African Americans, Italians, and Jews in the city to unseat the Irish incumbent, Leo Carlin. Stalks was the consummate inside politician with Mayor Addonizio. Don Malafronte, close confidant of Mayor Addonizio said, ‘She believed the best way to influence the transition from white to Black was to integrate into the power structure.” People of that generation believed you had to stay close to power, to be there when the transition is made. She was younger than the ministers and politicians around her, “but tough!” She was oriented toward working with the Democratic Party and through City Hall, all the way. And it worked for her. She was appointed Executive Secretary of the Central Planning Board and eventually Director of Health and Welfare– two “firsts” for Blacks, and women too.

Stalks hoped for a smooth transition for Black people into power, maybe even somebody in her family. She was an integrationist, and believed in a gradual approach. However, she was eventually confronted with a younger generation that was motivated more by suffering of the people and wanted to move faster. As a member of both the Addonizio administration and vice president of the moderate Newark branch of the NAACP, Stalks found herself in the middle of power struggles between conflicting generations and ideologies.

References:

Josephine Bonomo, “Path to Top Doubly Hard For Women Executives,” Newark News, October 13, 1968.

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation.

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power.

Junius Williams Interview with Donald Malafronte, June 6, 1986.

Larrie West Stalks describes working from “inside” City Hall to fight for Black equality and empowerment. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

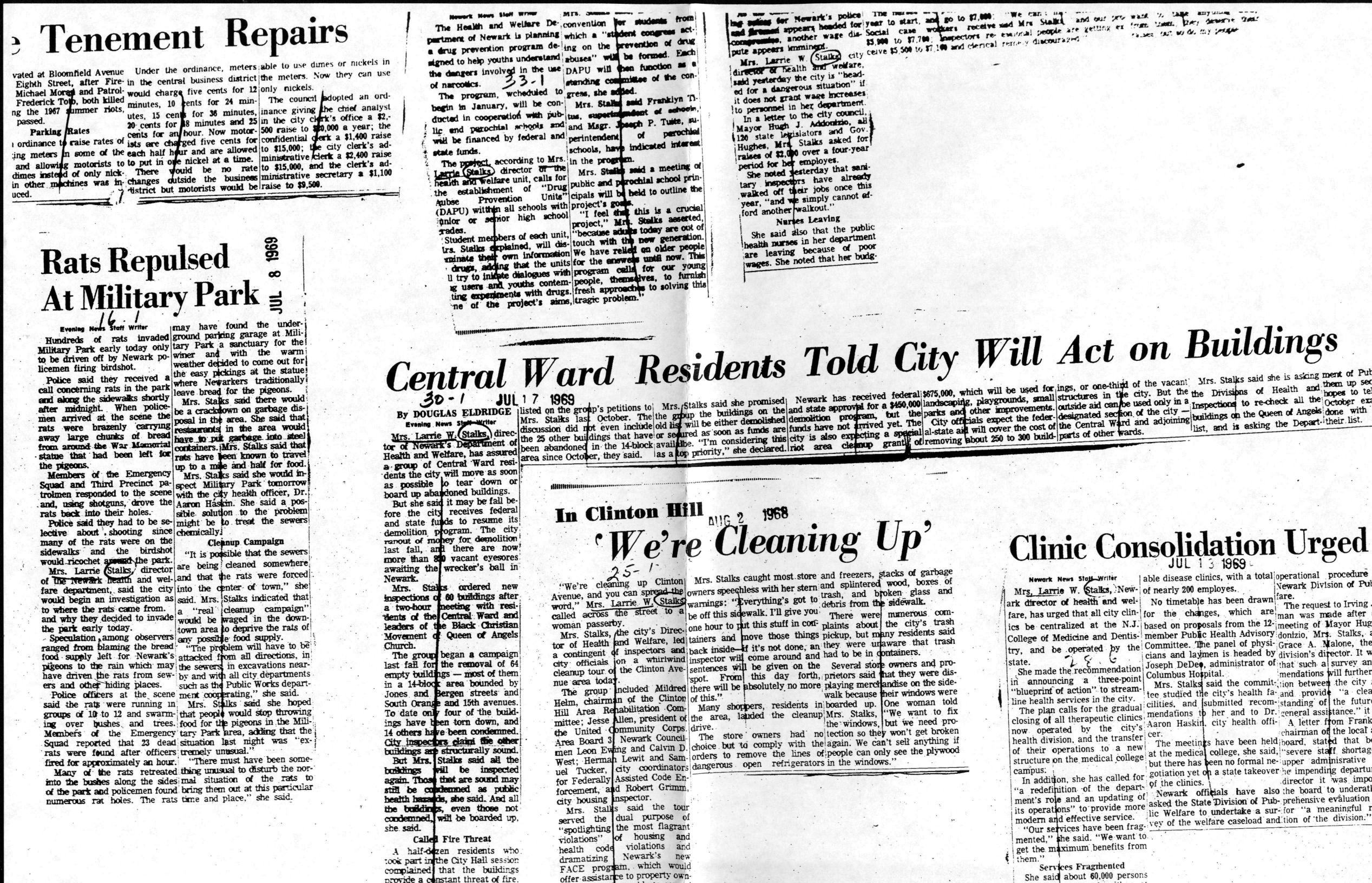

A collection of newsclippings from the Newark Evening News in the 1960s covering the political career of Larrie West Stalks. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Former City Councilman Calvin West discusses the political experiences of his sister, Larrie West Stalks. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Former Deputy Mayor Paul Reilly discusses Larrie West Stalks’ appointment as Executive Secretary of the Central Planning Board during the Addonizio administration. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection