The Medical School Negotiations

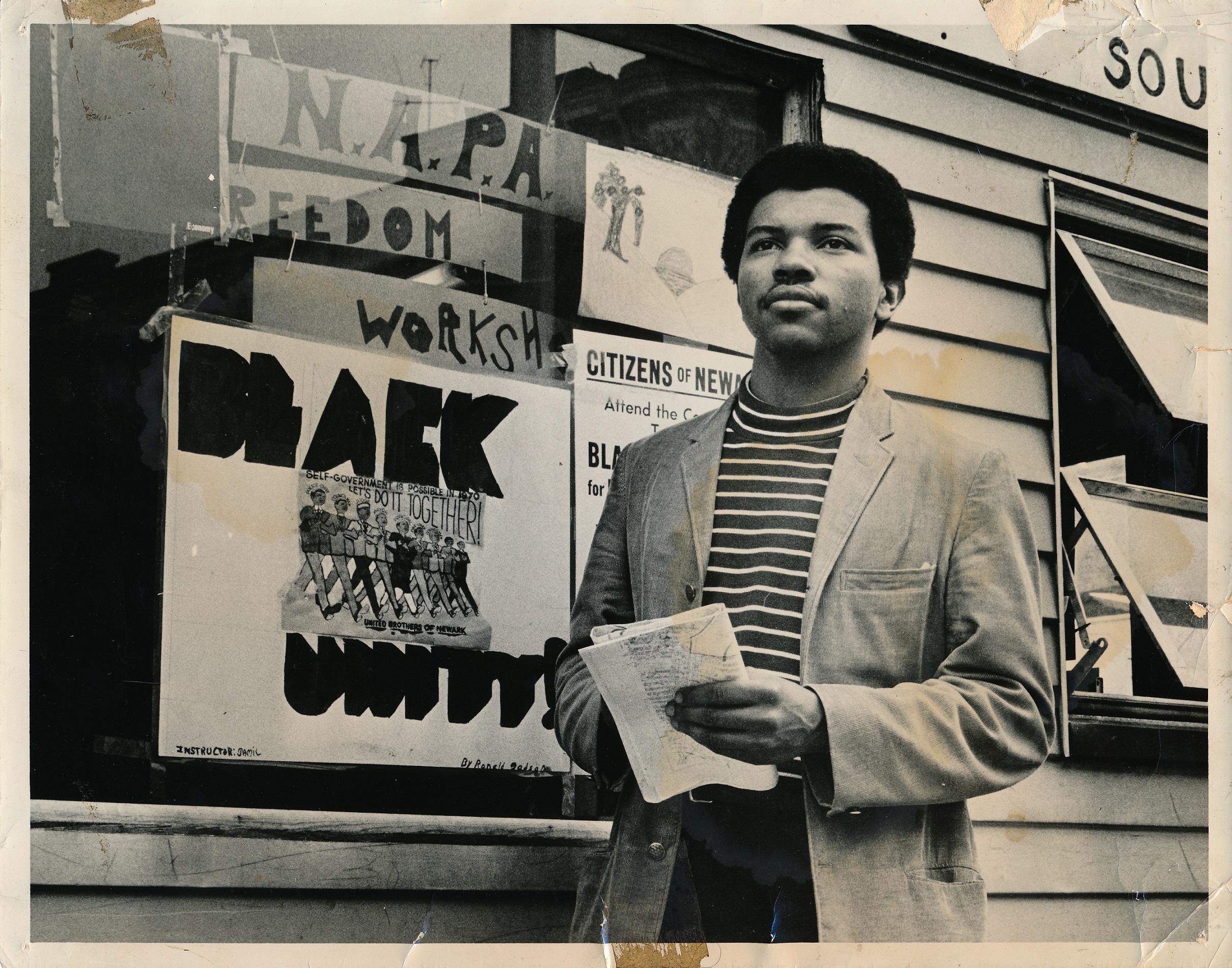

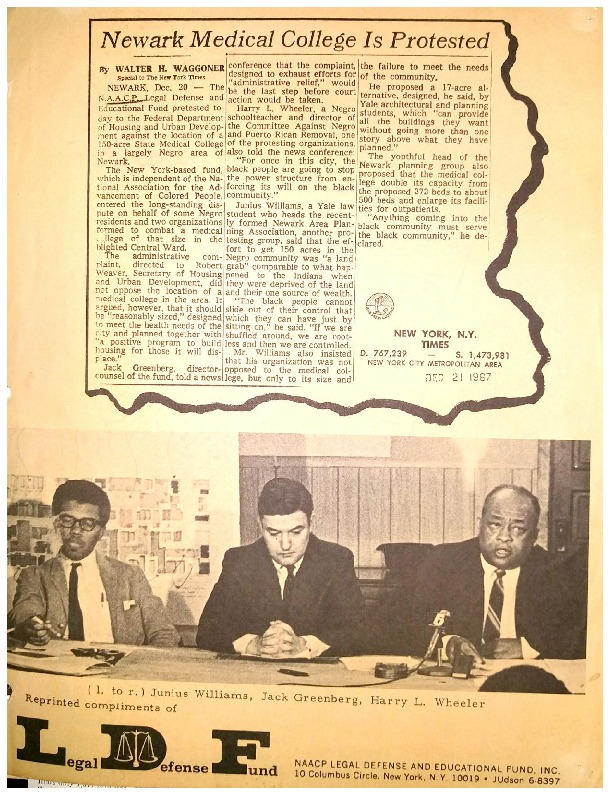

Junius Williams, a Yale Law School graduate who had come to Newark to participate in the SDS Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) in the South Ward, became the principal organizer and leader of the second stage of the struggle against the medical school plans….

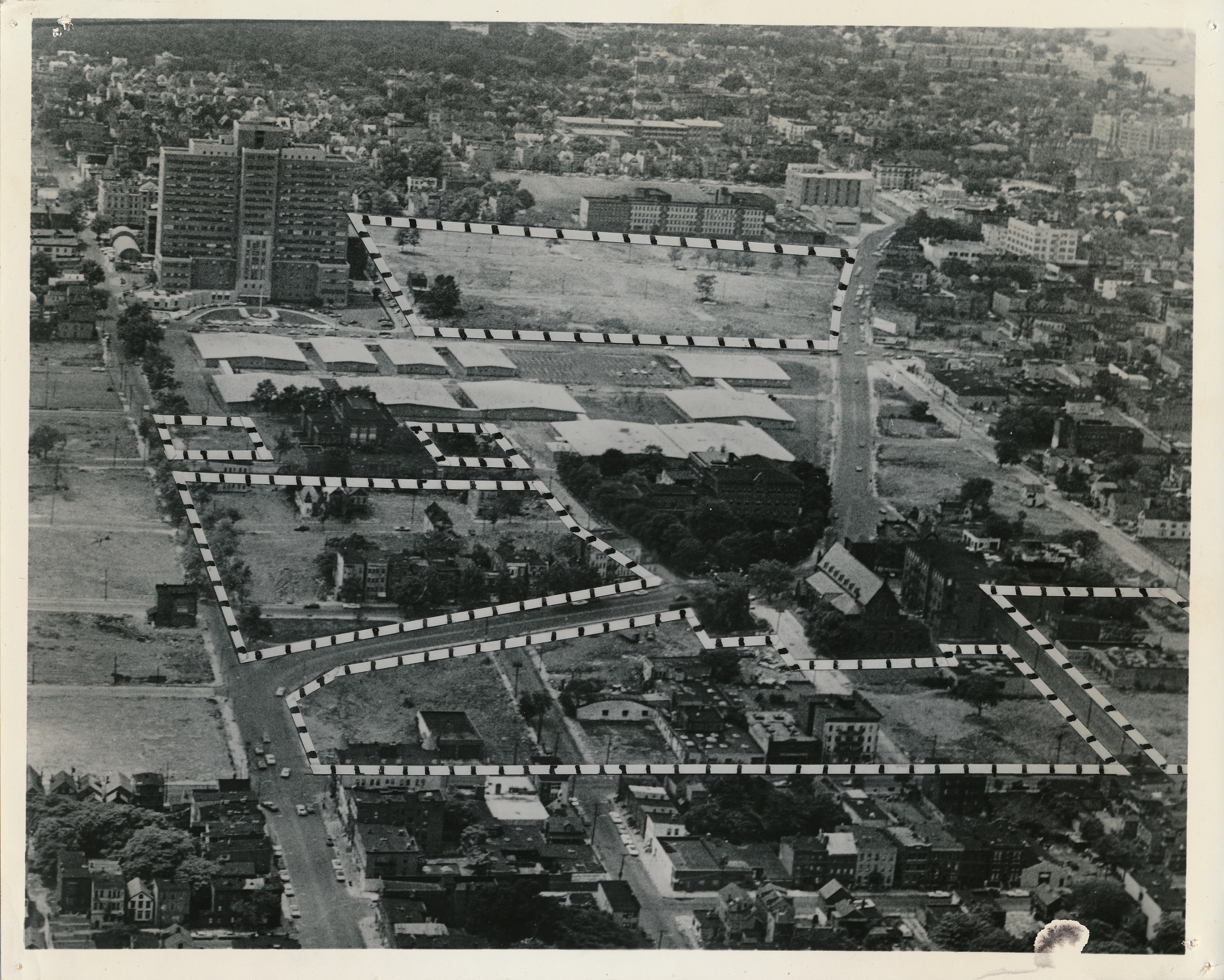

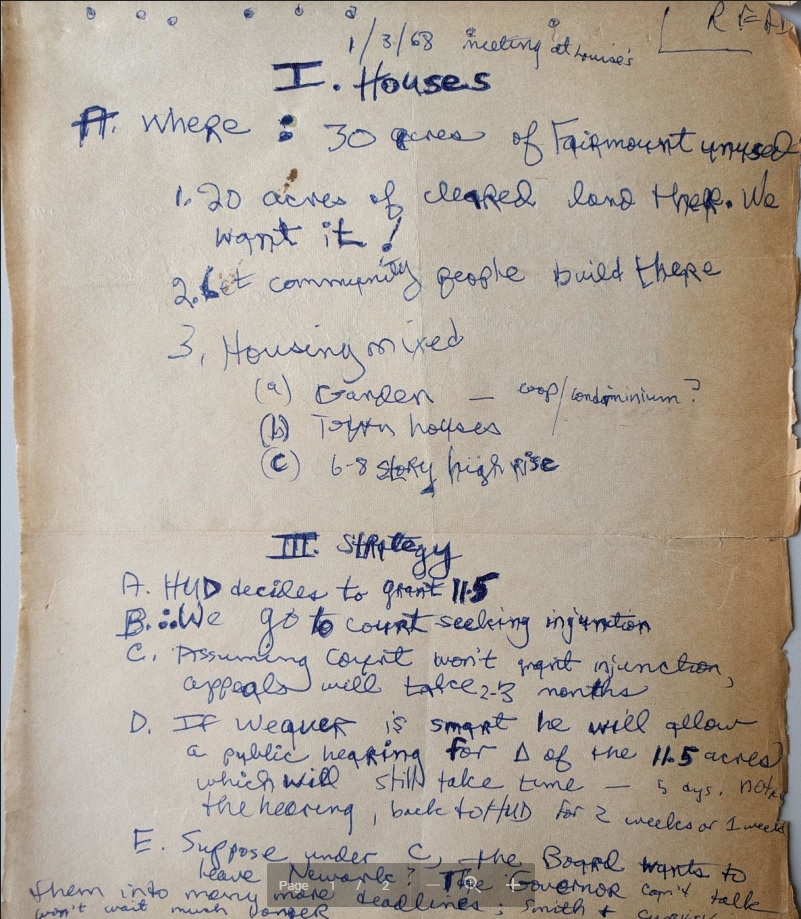

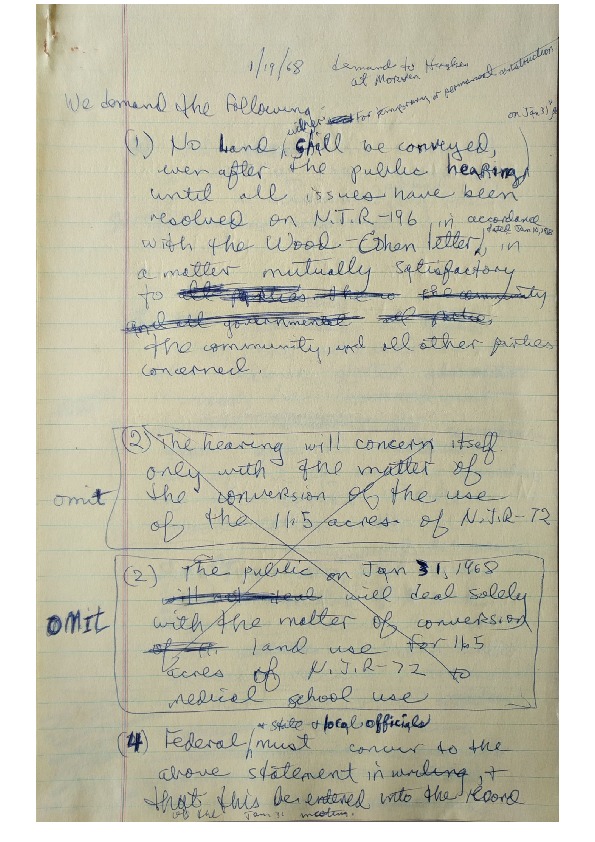

The July rebellion changed the thinking of authorities, particularly officials in Washington who were key in providing resources for the medical school project. In January 1968, a letter signed by Robert Wood, undersecretary of Housing and Urban Development, and Wilburn Cohen, undersecretary of Health, Education and Welfare, advised Governor Hughes that requirements for community participation of the Model Cities act had to be met if the medical school project, which was slated to receive $35 million in federal funds, was to be approved. In effect, the letter directed school officials and the NHA to yield to community demands for a much smaller site. The letter further spelled out seven areas relating to the building of the institution that had to be satisfactorily addressed in the discussions between community groups and state authorities. The areas included the size of the site, relocation plans for displaced residents, job opportunities for minorities in construction of the institution, health and education services that the new hospital would provide, jobs for residents in the institution, special efforts to recruit minorities for medical training, and an upgrade of Martland, the city hospital that served Newark’s poor.

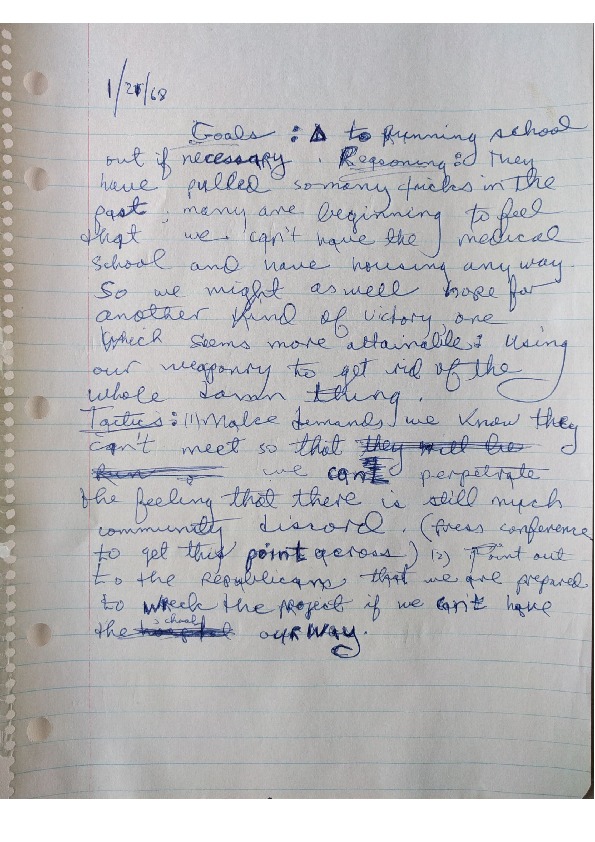

Governor Hughes then announced that community groups could negotiate with city, state, and federal officials on the terms of the project in accord with the mandate laid out in the Wood-Cohen letter. Several months of negotiation followed with Junius Williams, Louise Epperson, and Harry Wheeler, leading a team of community representatives sitting on one side of the table, advised by a group of experts in planning, law, and health. On the other side of the table sat state, federal, and local officials, including Lou Danzig, the Executive Director of the Newark Housing and Redevelopment Authority, and the president of the medical school, Dr. Robert Cadmus. The state chancellor of higher education, Ralph Dungan, facilitated the negotiations, along with Paul Ylivisaker, the Commissioner of the state Department of Community Affairs. For the first time, Danzig had to face questions about his decision making, reveal the names of developers to whom he had committed parcels of land, and openly discuss how he planned to relocate the thousands of people and businesses in the area. His commitments were frequently vague and evasive as he attempted to limit the amount of information available to the community. The negotiations were not only a public discussion about urban renewal—they also represented a new and profound shift in the way redevelopment took place.

While the community had a negotiating team of people who had been meeting and planning the resistance to the medical school plans, the announcement of formal negotiations brought out others, including some from the Addonizio machine who challenged the right of the negotiating team to represent the community. There was clearly tension between the negotiating team and representatives of the medical school as well as tension between community representatives and city and NHA officials. Dungan ably managed the deliberations, and Epperson was a special force in the proceedings as well. When two black ministers attempted to interject their personal concerns into the discussions, she rose and said, “To the two good reverends, I am the person who started the crying and belly whining about the medical school coming to Newark … rang doorbells, stood in front of churches, gave out literature… I think you should have taken part in it and you didn’t, and you can’t speak now because you don’t know what you’re talking about. We been fighting … and no one of you came out and said one word about it. You sit and listen and take back to your community and then stand shoulder-to-shoulder and fight for it.”

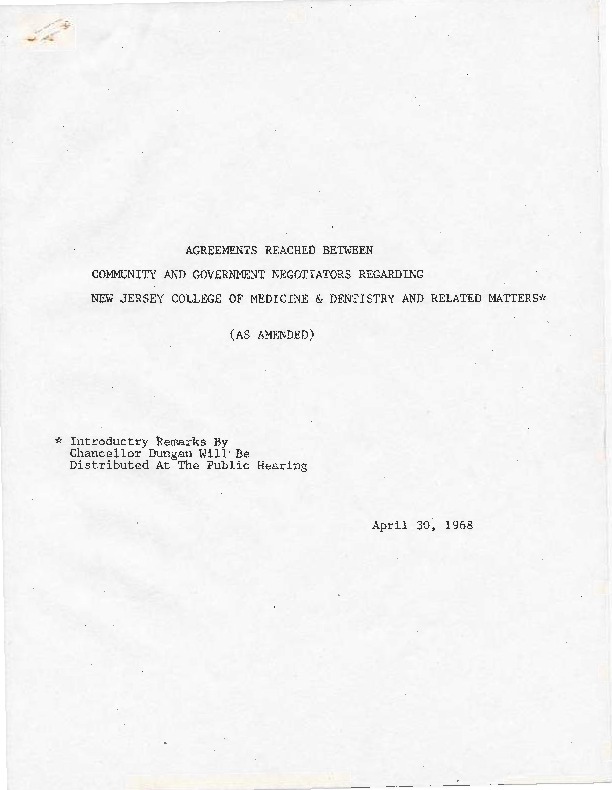

On March 15, 1968, the parties reached substantial agreement that included the following terms:

- The Medical School acreage was reduced from 150 to 57.9 acres

- The community was entitled to 63 acres of vacant urban renewal land for construction of housing and related facilities, to be planned and built by community non-profit organizations

- The workforce of the Medical School would include one–third of the journeymen and one-half of the apprentices as black and Puerto Ricans. There would be established a training group to train individuals in the skills necessary (eventually, the Newark Construction Trades training Council (NCTTC) and a Review Council to insure compliance composed of unions, contractors, sate, city and majority community representatives

- The Medical School would upgrade the health services available to the community by taking over the city hospital.

- The community would be majority stakeholders in a Health Review Council to monitor the quality of health care

- The Mayor was ordered to disband the Model Cities Citizen Advisory Board, and elections were to be conducted by the community to replace the old Board. The Board would have joint veto power with the city over plans forthcoming from the city

- The city and the Medical School would not begin construction on the site until there were adequate replacement dwellings for the people displaced. A Relocation review Board would be set up to review progress and give residents a place to make complaints.

Having the Agreements on paper was one thing. Making them actually happen was another story.

Clip from interview with community leader Louise Epperson, in which she describes how the Medical School Fight changed after the 1967 Newark rebellion. Epperson explains how she had a difficult time contacting any officials involved in the Medical School plans before the rebellion and how that changed afterwards. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from an interview with Newark Area Planning Association (NAPA) head Junius Williams, in which he describes how Newark’s Black and Puerto Rican communities continued the struggle against the proposed College of Medicine and Dentistry after the 1967 Newark Rebellion. NAPA led the charge to develop an alternate plan for the College of Medicine and Dentistry that would have originally displaced approximately 20,000 Black and Puerto Rican residents of the Central Ward. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

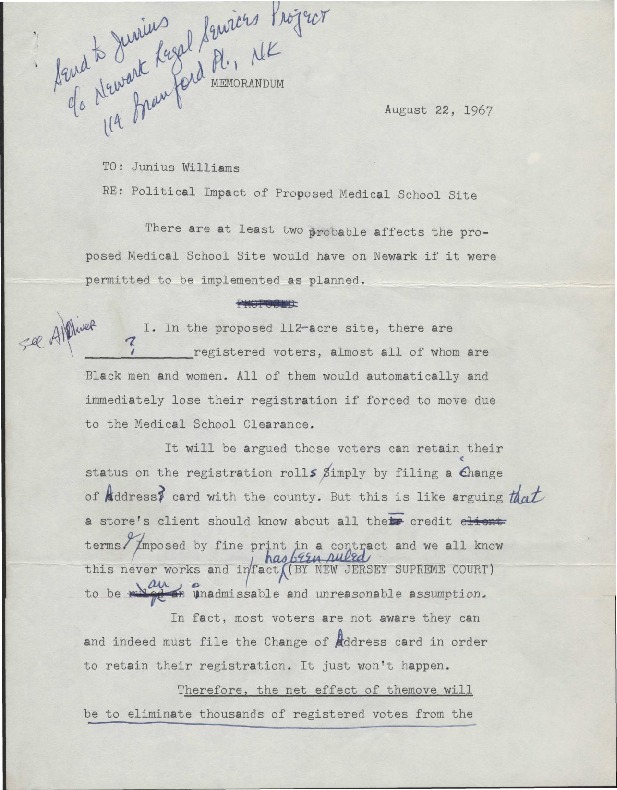

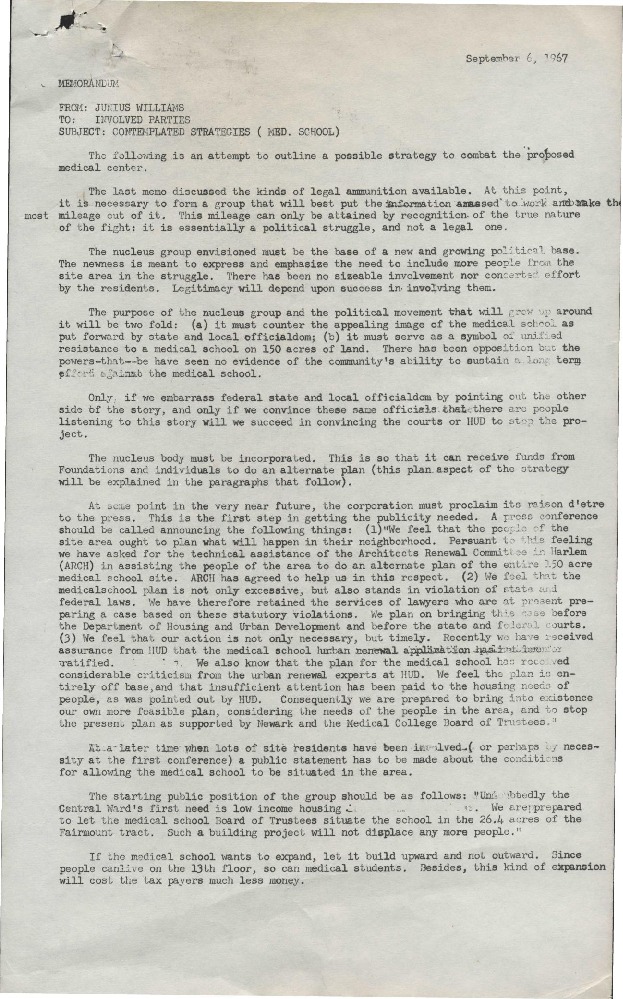

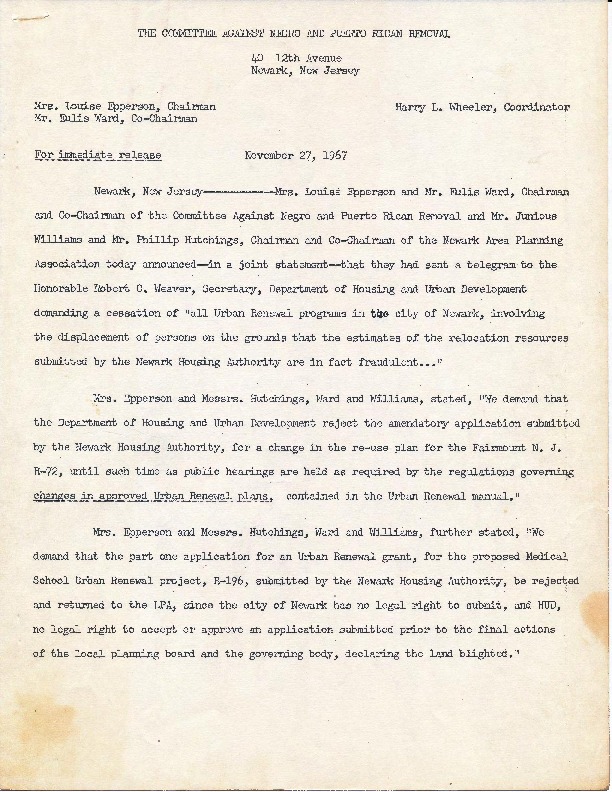

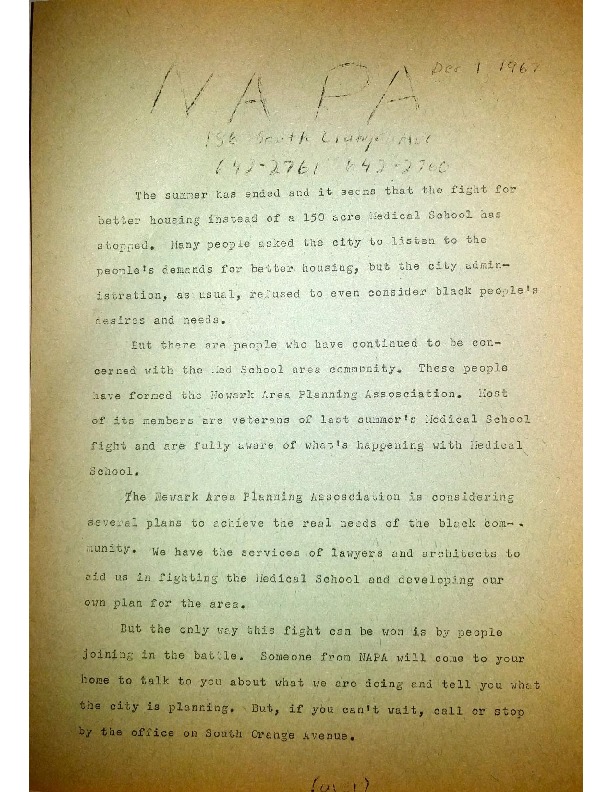

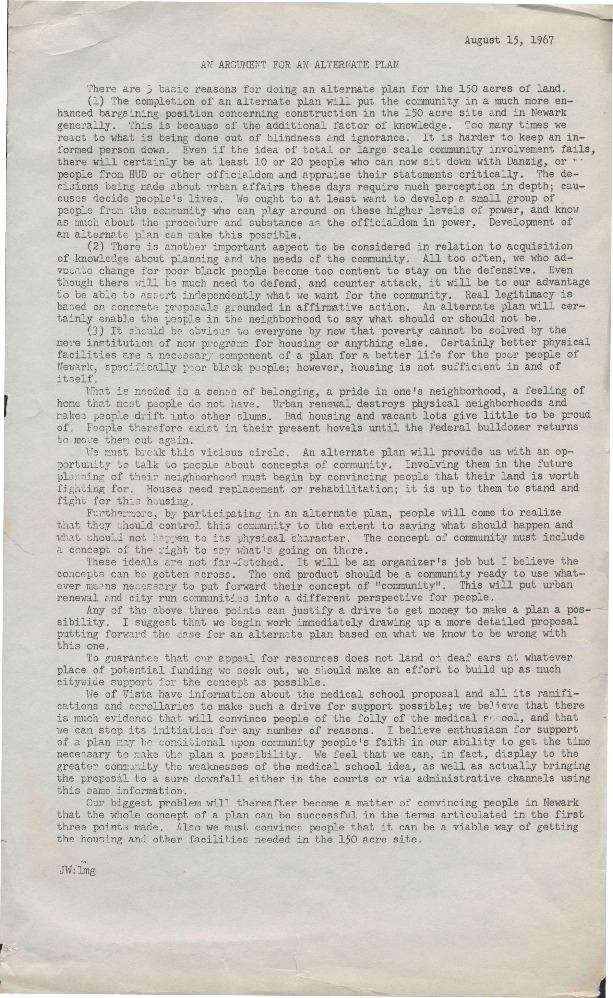

A statement prepared by the Newark Area Planning Association (NAPA) and law volunteers from Vista (Volunteers in Service to America) that put forth a comprehensive argument for an alternate plan for the development of the College of Medicine and Dentistry in Newark’s Central Ward. NAPA led the charge to develop an alternate plan for the College of Medicine and Dentistry that would have originally displaced approximately 20,000 Black and Puerto Rican residents of the Central Ward. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Explore The Archives