Interpretations

The most commonly used terms to define the week of upheaval in Newark in July of 1967 fall into two general categories: To some, a “riot” or “criminal insurrection” against society and law & order had taken place. To others, Newark had witnessed a “rebellion” or “uprising” against deep-seated issues of discrimination and inequality. As noted by historian Thomas Sugrue, “The terms that commentators chose—‘civil disorder,’ ‘disturbance,’ ‘riot,’ ‘rebellion,’ ‘uprising’—signaled their position on the meaning of the events.”

Those who labeled the events as “riots” argued that widespread looting, destruction, and violence represented “senseless” mob actions carried out by criminals and extremists. After touring the Central Ward on July 14, Governor Hughes described the events as “a criminal insurrection against society, hiding behind the shield of civil rights.”

Those who labeled the events as a “rebellion” saw something meaningful in the actions- a lashing out against economic, political, and social systems that had oppressed black communities for far too long. According to poet and activist Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), “Here in Newark there was apartheid, generally, until those rebellions. It was those rebellions that was the force, the violent force, to end American apartheid.”

The language that people used to define these events is important because it provides insights into the actions they took in response to the “riots” or “rebellions.” Governor Hughes saw a “criminal insurrection against society,” so he responded with deadly military force to put down the “insurrection.” Community activists, like Frederica Bey, believed the “rebellions…showed that black people had some life after 400 years of servitude” and consequently sought to mobilize that energy for black political empowerment in the days, months, and years after the rebellion.

References:

Sandra King, “Newark: The Slow Road Back”

Thomas Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North

Clip from the documentary film, “Newark: The Slow Road Back,” in which Dr. Cornel West explains the political significance of the 1967 Newark rebellion. As urban unrest swept the nation during the Civil Rights Movement in the mid-to-late 1960s, people argued about how these conflicts should be defined. While some call them “riots,” Dr. West refers to the unrest as “rebellion.” — Credit: Sandra King

Clip from the documentary film “Newark: The Slow Road Back,” in which Governor Richard Hughes recalls his experiences and actions during the 1967 Newark rebellion. The clip also includes interview footage from Hughes during the rebellion stating that “those involved are criminals in my judgement…I think the American people are pretty tired of this cloak of civil rights activity shielding this criminal activity.” — Credit: Sandra King

Explore The Archives

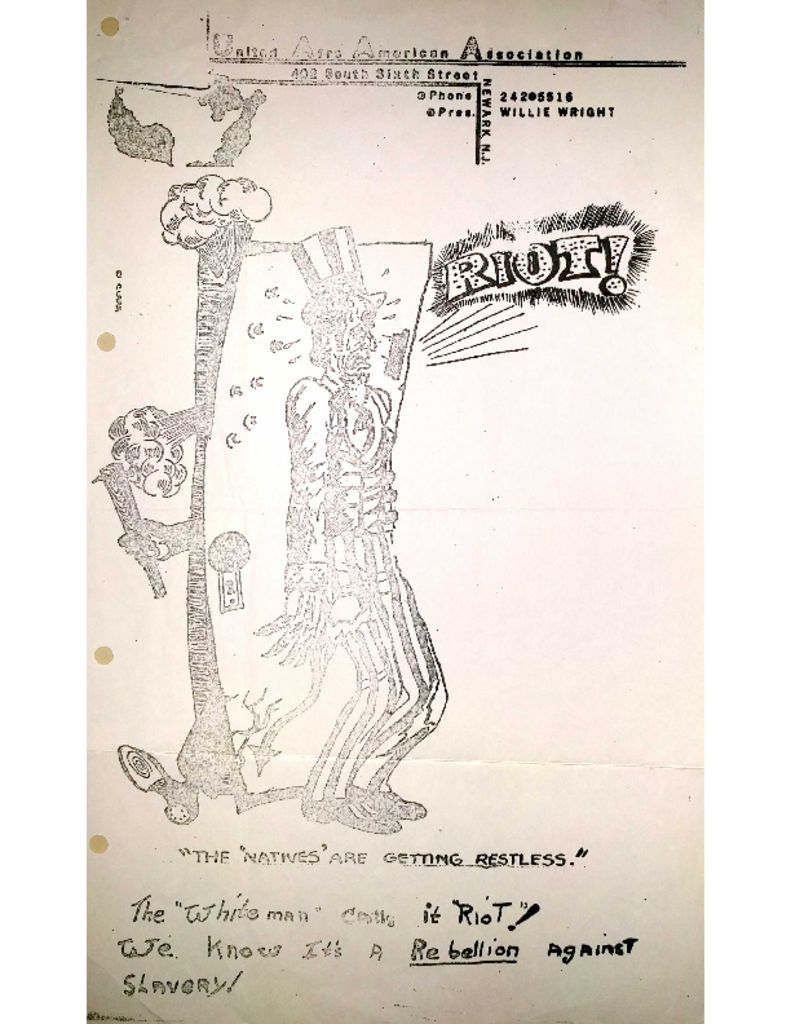

Poster distributed by the United Afro American Association after the 1967 Newark rebellion. The poster depicts Uncle Sam as a devilish figure, yelling “Riot!” as he struggles to hold back a black man with a club. Many in Newark’s Black communities saw the July events as “rebellions” or “uprisings” against oppression, while white communities and politicians viewed them as “riots” against law and order. — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

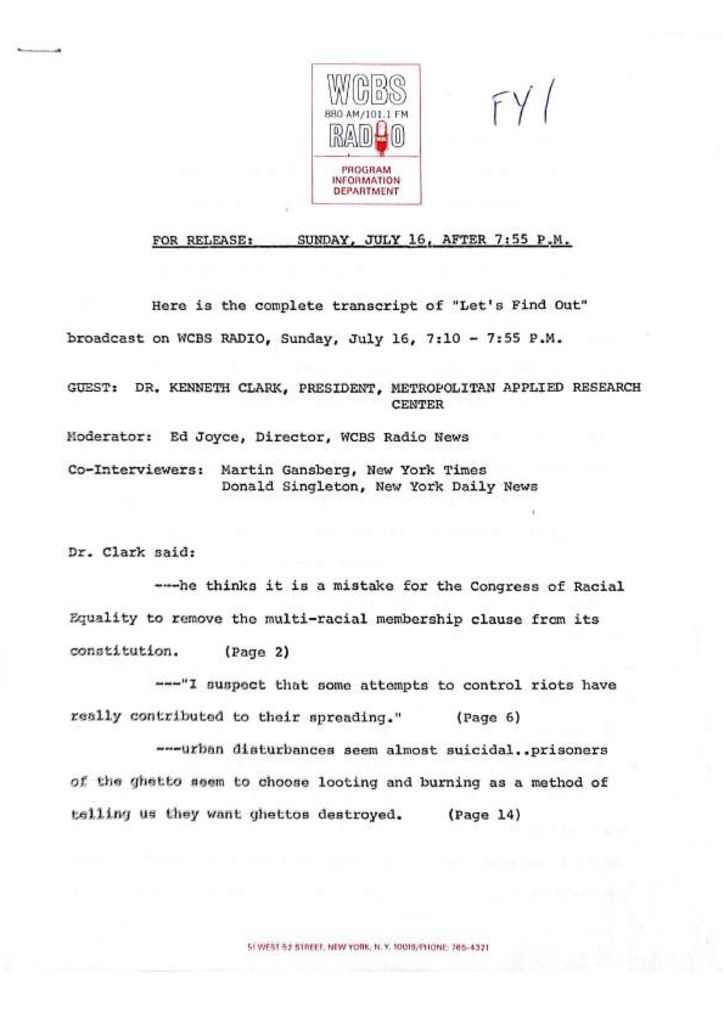

Transcript of a WCBS radio interview with Dr. Kenneth Clark on July 16, 1967, in which he discusses his interpretations and analysis of the ongoing rebellions in Newark. In the interview, Dr. Clark says “as a psychologist, I would suggest the hypothesis that in some unconscious way, or maybe not so unconscious, incoherent, way the rioting people are saying, we want this destroyed… They’re saying, you know, it’s the only way that we’ll get change.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

Clip from the documentary film “Newark: The Slow Road Back,” in which poet, playwright, and activist Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) provides his interpretation of the 1967 Newark Rebellion. Baraka describes the rebellion as “the violent force to end American apartheid.” — Credit: Sandra King

Clip from interview with North Ward resident Anthony Imperiale, in which he claims that the 1967 Newark rebellion was planned by “Black militants.” This perception of protests or rebellions as being orchestrated by “outside agitators” was a popular misinterpretation throughout the Civil Rights Movement. This interpretation was most prominently seen in the 1968 Hearings Before the House of Representatives Committee on Un-American Activities on “Subversive Influences in Riots, Looting, and Burning.” — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

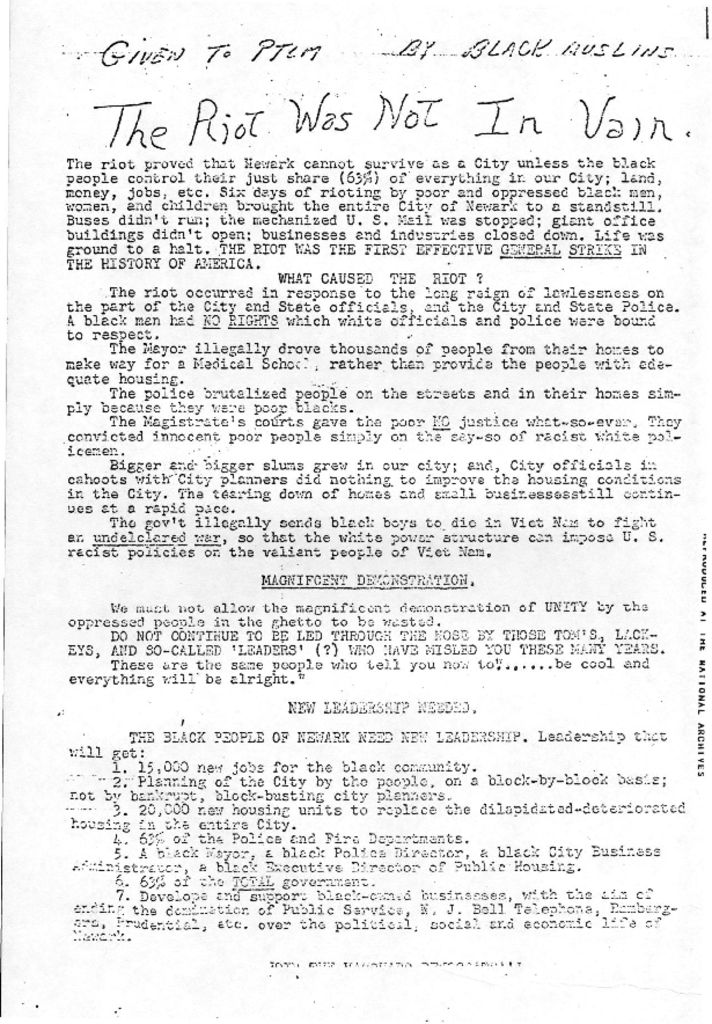

Leaflet distributed by the Vanguard Democrats, a progressive political organization in Newark, on July 22, 1967. The leaflet proclaims, “We must not allow the magnificent demonstration of UNITY by the oppressed people in the ghetto to be wasted,” and provides a list of objectives for Black political, social, and economic empowerment. — Credit: Junius Williams Papers

The Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder

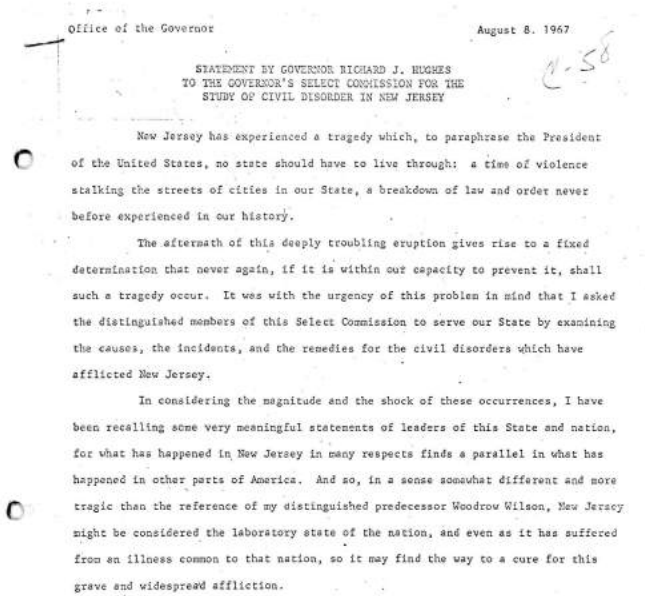

On August 8, 1967, New Jersey Governor Richard Hughes asked the members of the newly formed Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder to “examine the causes, the incidents, and the remedies for the civil disorders which have afflicted New Jersey.” Speaking to the ten-member Commission, Governor Hughes urged, “It is most important that the Commission…shall point the way to the remedies which must be adopted by New Jersey and by the nation to immunize our society from a repetition of these disasters.” With these instructions, the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder embarked on a five-month venture to study the deep-seated problems facing the City of Newark and issue a report on its findings to the city, state, and nation.

According to community activist Robert Curvin, who testified before the Commission, “The inquiry followed a model similar to that of a grand jury, where the building blocks of information based on facts, details, and credible stories from many different points of view and angles lead to a strong, powerful conclusion.” During its five-month operation, the Commission heard testimony from a cross-section of Newark residents, including civil rights activists, police officers, politicians, lawyers, clergy, community residents, and business owners.

After conducting 65 meetings and 106 interviews, the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder published its findings and recommendations in a two-hundred-page report titled Report for Action. In its report, the Commission concluded that the 1967 Newark rebellion resulted from the unwillingness of city and state governments to address longstanding issues of political, social, and economic inequality and oppression in the city.

The report consisted of three sections. The first, “Sources of Tension,” examined issues of discrimination and inequality in the areas such as politics, employment, housing, education, welfare, healthcare, and policing. The second, “The Disorders,” provided a chronological review of the 1967 Newark rebellion and critically analyzed the actions of law enforcement agencies during the rebellion. The third, “Recommendations,” presented the Commission’s suggestions on ways to address the critical issues of discrimination and inequality within the city, as well as policy recommendations for “the control of civil disorders.”

The Commission’s lengthy report was met by mixed responses in the city. To African-American community leaders, such as Reverend Kim Jefferson and future mayor Ken Gibson, the report was received positively. Jefferson called the report “a real and lasting contribution to the people of this state and indeed of our nation,” while Gibson endorsed the report and called for an additional commission to ensure implementation of the Commission’s recommendations. To members of law enforcement agencies, though, the report represented a direct attack on police. The Patrolmen’s Benevolent Associations of the city and state lashed out at the Commission’s “accusations and allegations” of police brutality, as well as its recommendation to create a civilian police review board.

Although the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder has been widely revered as “one of the most complete documents ever produced to investigate civil disorders at the state level,” most of its recommendations went unfulfilled. Of the ninety-nine recommendations made by the Commission, only twenty-six were actually implemented. Addressing the lack of action on the Commission’s recommendations a year after its publications, one of the members forewarned, “If we can accomplish a democratic redistribution of political power, the glory of that achievement will rest on us all. If we cannot or will not embark on such an undertaking, we may very well attend at the funeral of this city and the dreams of its desperate people.”

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation.

Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action.

Transcript of address given by Governor Richard J. Hughes to the Governor’s Select Commission for the Study of Civil Disorder in New Jersey on August 8, 1967. The Commission was convened by Governor Hughes to study “the causes, the incidents, and the remedies” for the 1967 Newark rebellion. The Governor’s Commission, also known as the Lilley Commission after its chair Robert Lilley, held months of hearings from Newark residents and later published its findings in Report for Action.

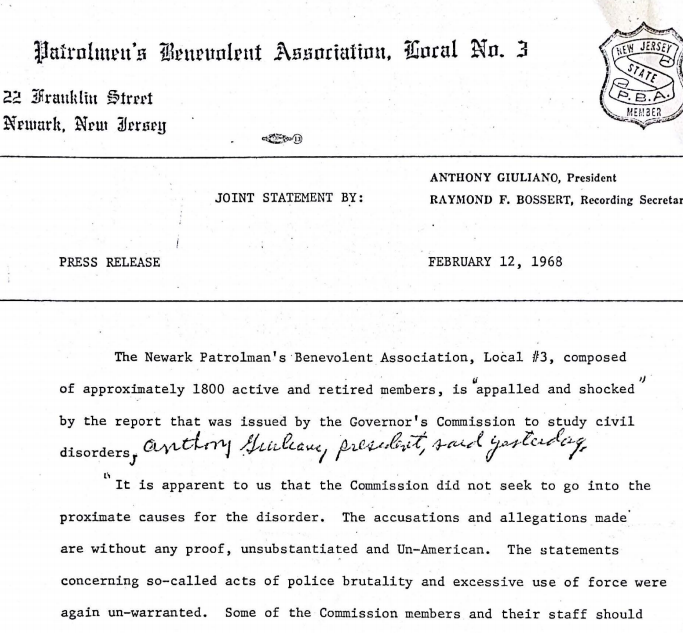

A February 12, 1968 press release from the Newark Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (PBA) issued in response to the report of the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder. The Commission was convened by Governor Hughes to study “the causes, the incidents, and the remedies” for the 1967 Newark rebellion. The press release, prepared by Anthony Giuliano and Raymond Bossert, claimed “The accusations and allegations made [in the report] are without any proof, unsubstantiated and Un-American.”

Explore The Archives

Excerpt from a pamphlet distributed by the Church in Metropolis organization to summarize the findings of the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder. The pamphlet contains a compilation of newsclippings from the Newark Evening News related to the Commission’s Report and a summary of its recommendations. — Credit: Newark Public Library

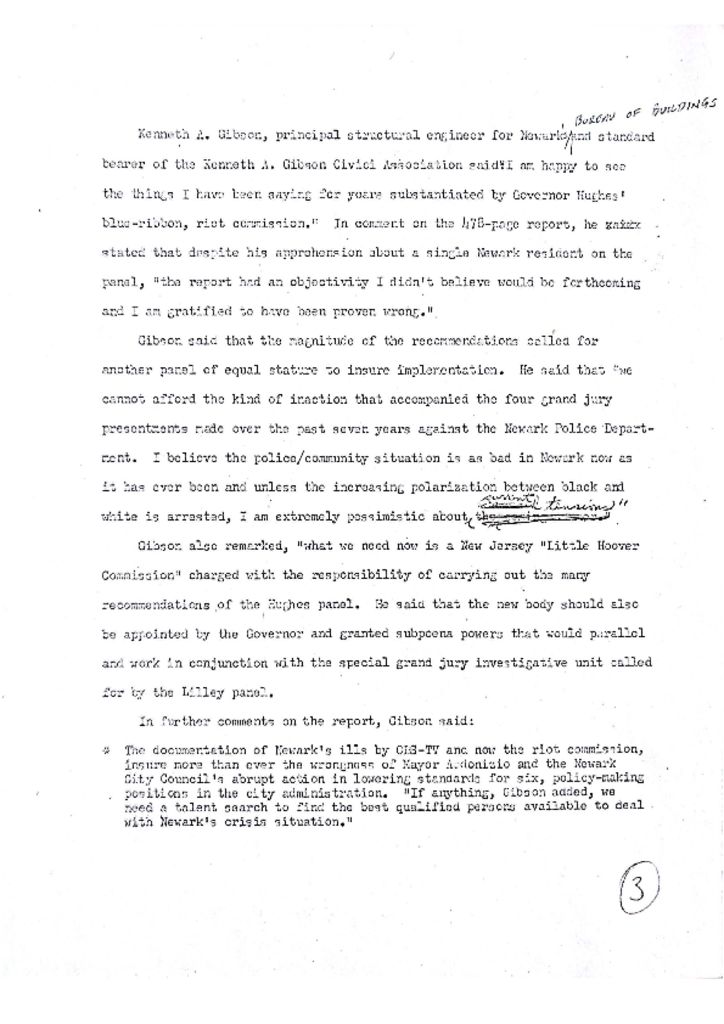

Draft article by Newark Evening News reporter Doug Eldridge describing Ken Gibson’s comments on the report issued by the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders. Gibson, a member of Newark’s Business Industrial Coordinating Council (BICC) and 1966 mayoral candidate, became the first African-American mayor of Newark in 1970. — Credit: Newark Public Library

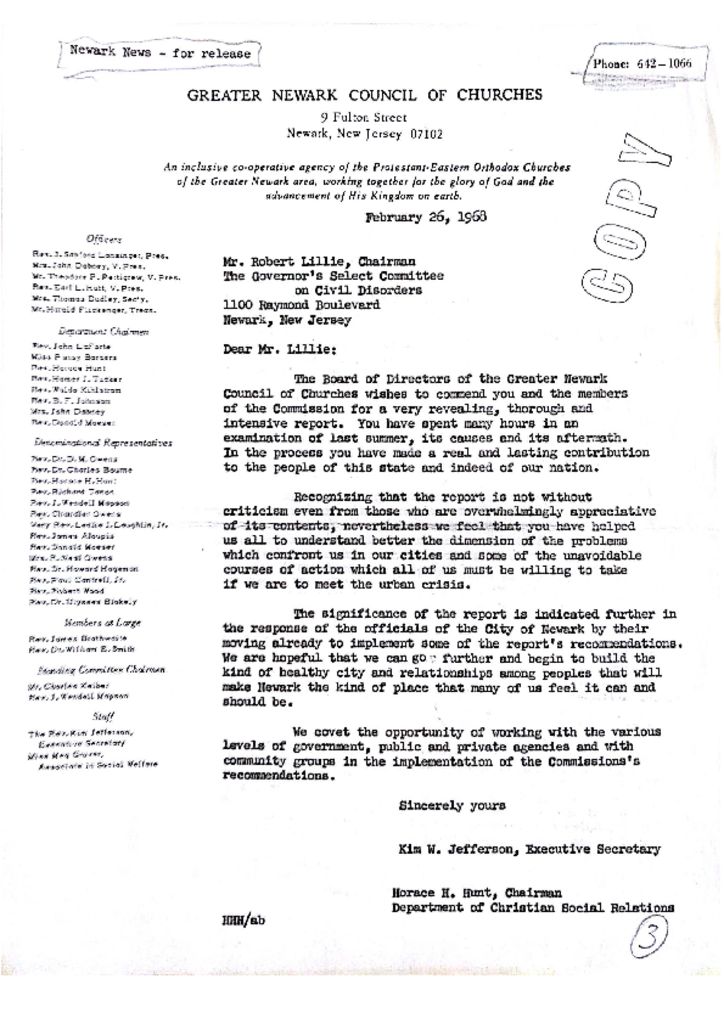

Letter from Rev. Kim Jefferson, Executive Secretary of the Greater Newark Council of Churches, to Robert Lilley, chairman of the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder, on February 26, 1968. The Commission was convened by Governor Hughes to study “the causes, the incidents, and the remedies” for the 1967 Newark rebellion. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Leaflet distributed by the Vanguard Democrats, a progressive political organization in Newark, on July 22, 1967. The leaflet proclaims, “We must not allow the magnificent demonstration of UNITY by the oppressed people in the ghetto to be wasted,” and provides a list of objectives for Black political, social, and economic empowerment. — Credit: Junius Williams Papers

A February 19, 1968 press release from the New Jersey State Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (PBA) issued in response to the report of the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder. The Commission was convened by Governor Hughes to study “the causes, the incidents, and the remedies” for the 1967 Newark rebellion. In response to the Commission’s recommendation to establish a civilian police review board in Newark, the PBA stated “the creation of a civilian police review board will be fought with every weapon at the command of the State PBA.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

Address given to the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders by an unidentified member of the Commission, about a year after the publication of the Commission’s findings in Report for Action. In this address, the speaker criticizes the city of Newark and State of New Jersey for failing to implement the vast majority of the recommendations of the Commission, “the fulfillment of which it considered mandatory to the establishment of order and justice.” Only 26 of the Commission’s 99 recommendations were implemented. — Credit: Newark Public Library