Puerto Rican Political Movements

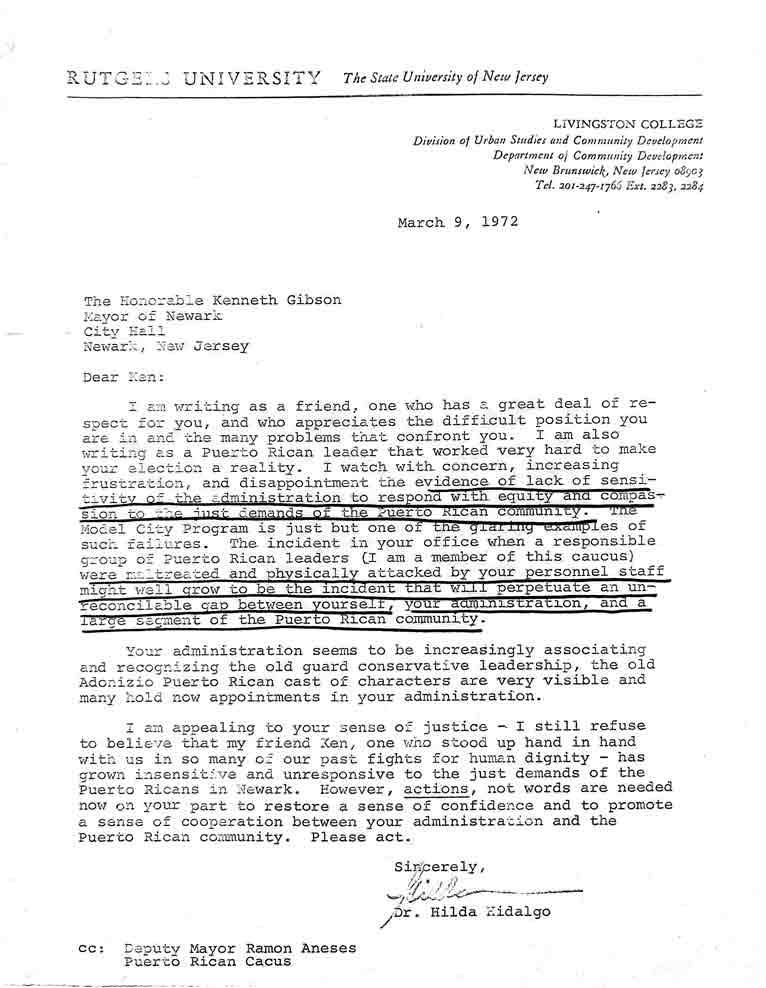

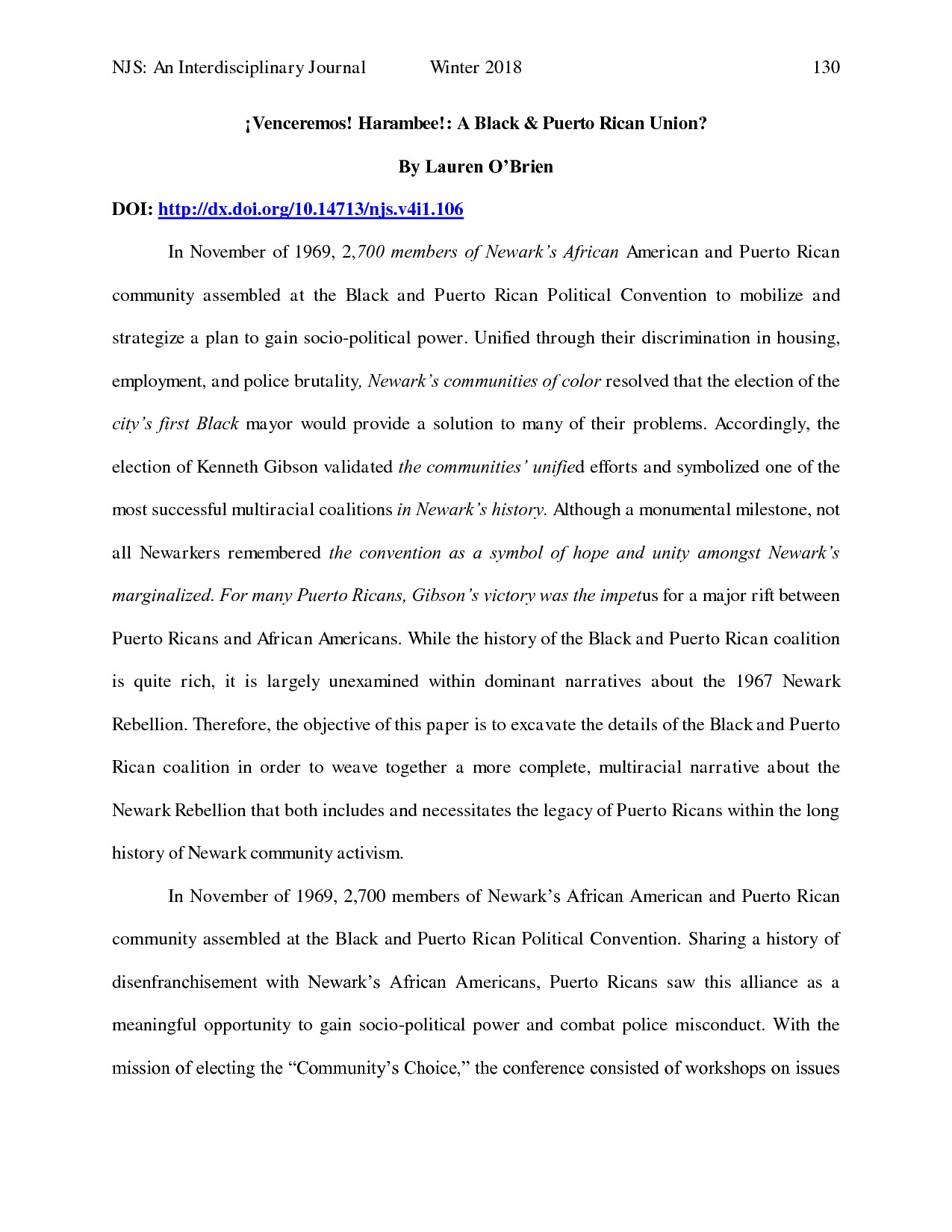

In 1969, members of the growing Puerto Rican community came together with the African American community to select Kenneth Gibson as their candidate for mayor of Newark during the Black and Puerto Rican Convention. The convention supported Puerto Rican leader Ramon Aneses as a candidate for councilman at-large. He was appointed as deputy mayor by Mayor Gibson after he failed to win a seat in the 1970 election. However, the election of Gibson itself would not mark the ascent of the political visibility of Puerto Ricans; instead, it would take another violent public disturbance to do so.

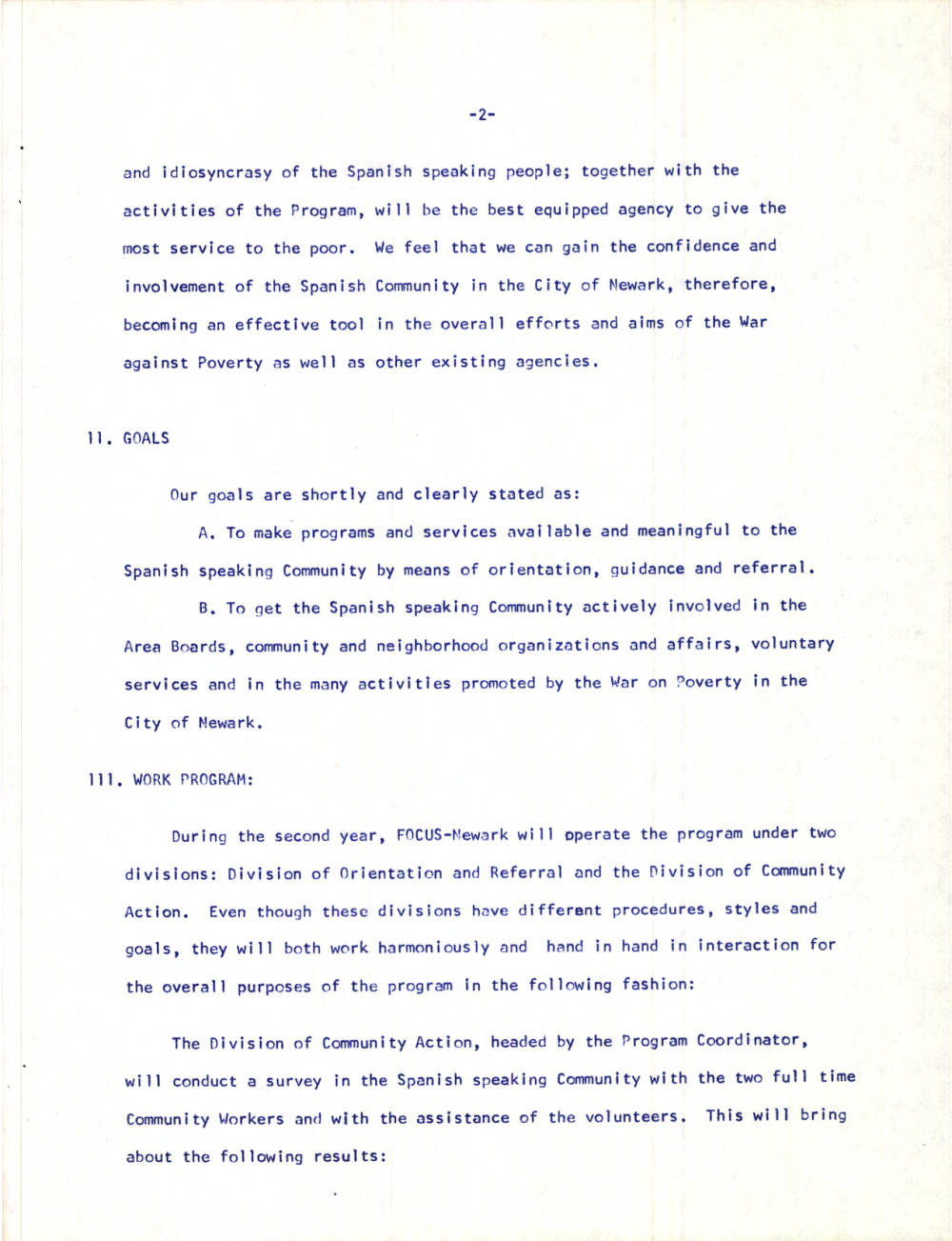

In 1970, Puerto Rican people made up approximately 12 percent of the population of Newark, with most settling in the predominantly Italian North Ward. Like African American migrants to urban centers, the process of assimilation was uneven for Puerto Ricans in Newark. In the United States, where racial tension is usually understood in a binary way, between white and Black, Puerto Ricans have occupied a unique racial middle-ground. Moreover, they often faced a language barrier, and their cultural practices set them apart as well. Emphasizing that very point, in 1966 a group of eighty residents, Jose Rosario, Hilda Hidalgo, and Zain Matos, called for the formation the Field Orientation Center for the Underprivileged Spanish (FOCUS) after their own research revealed that the Spanish-speaking community was not being adequately served by the United Community Corporation (UCC), which headed the War on Poverty programs in Newark. While FOCUS was formed and granted some federal money, the amount they received, $24,000, was one-tenth of what they requested. Additionally, their repeated demands for the UCC Board of Trustees to have more representation from the Puerto Rican community and for more financial support for programs that benefited the Puerto Rican community were met with resistance by the mostly Black leadership of the UCC.

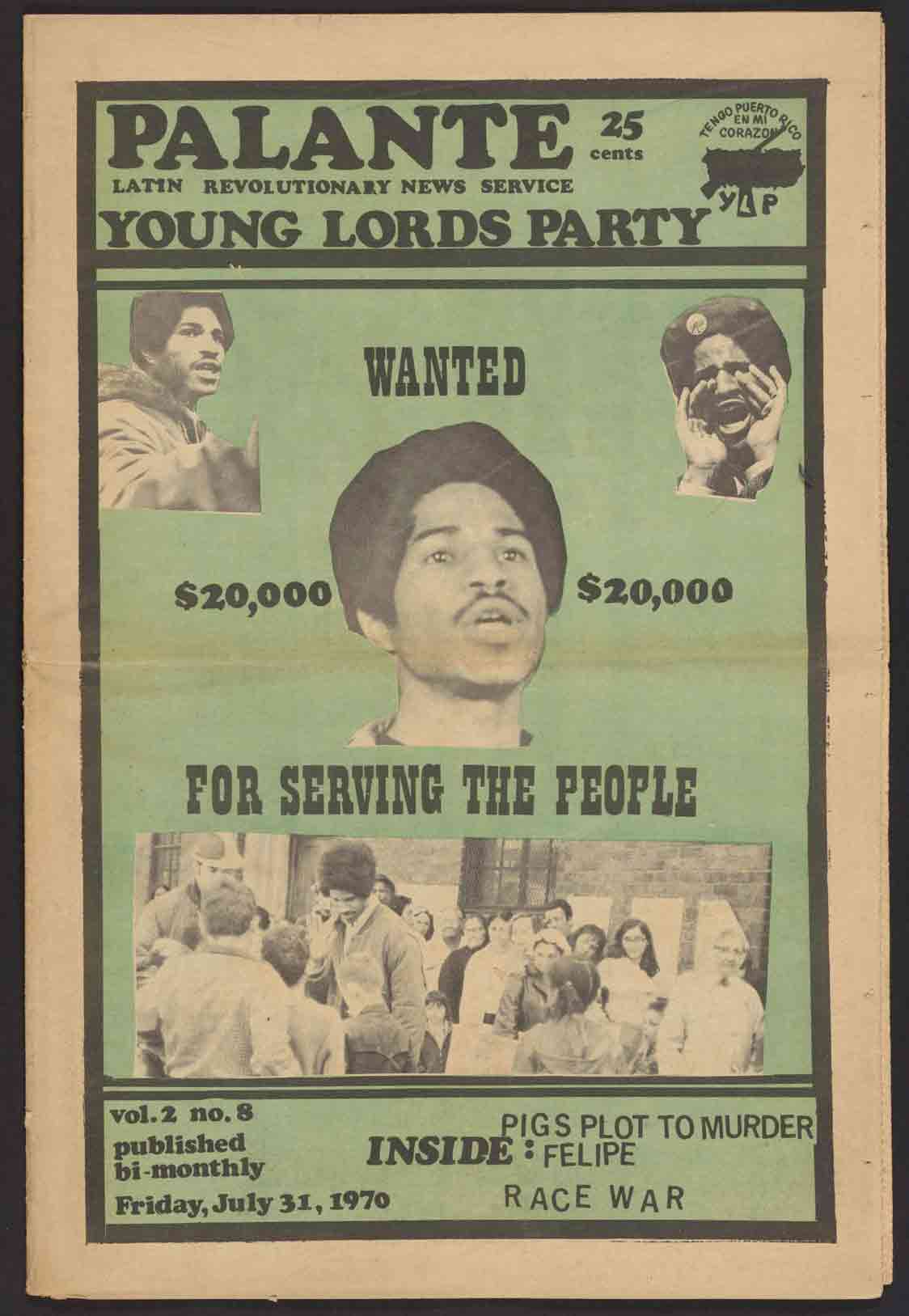

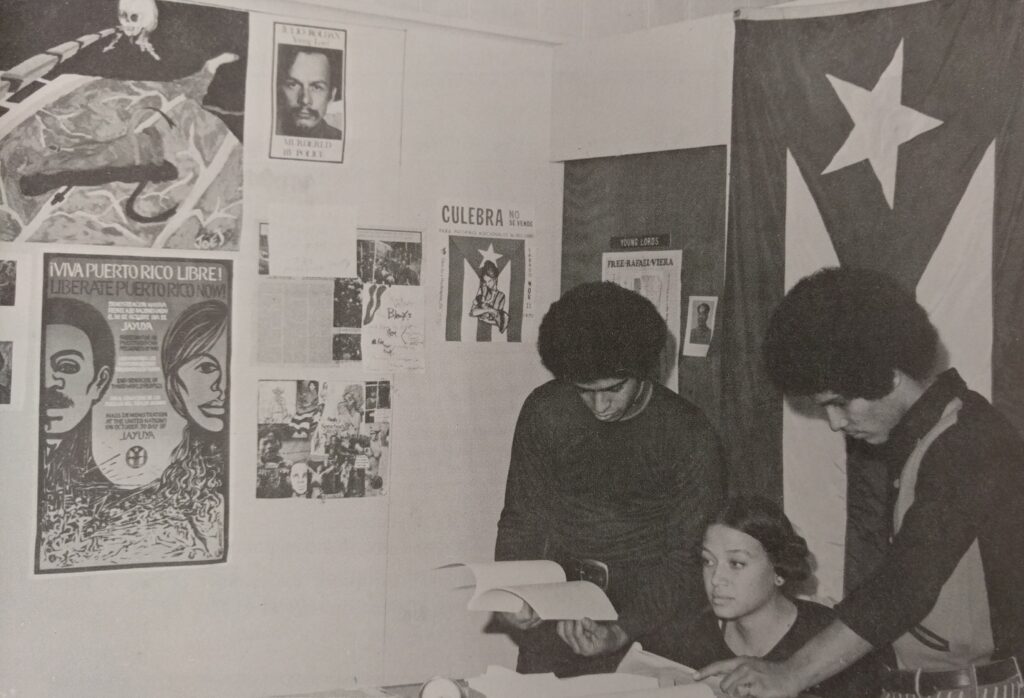

In response to a general lack of representation in the city’s social, economic, educational, and political sectors, Newark’s Puerto Rican communities continued building their own organizations for collective empowerment. In early 1969, ASPIRA was formed by a group of educators and professionals to support the development of Puerto Rican community leaders. That fall, the Young Lords established an office at 75 Park Ave. in Newark’s North Ward (now the office of La Casa de Don Pedro). Inspired by Puerto Rican traditions of anti-colonial struggle, the revolutionary nationalism of the Black Power Movement, and the militancy of the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords evolved from a street gang to a grassroots movement in Chicago to fight for self-determination in Puerto Rican communities. Young Lords organizations quickly emerged around the country, most notably in New York City. The Newark Young Lords formed in October 1969 through the leadership of Ramon Rivera, then in his early 20s.

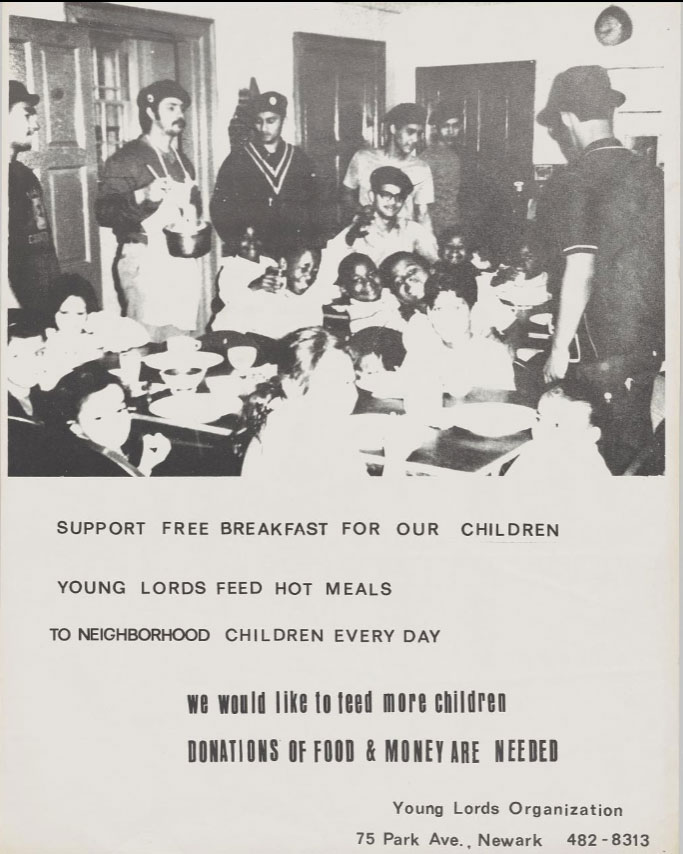

Through Rivera, the Young Lords built relationships with Black-led organizations like Amiri Baraka’s Committee For Unified Newark (CFUN), signing a mutual defense pact against police brutality and joining the planning committee of the Black and Puerto Rican Convention. In early 1970, the Newark Young Lords began a free breakfast program for children, modeled after those operated by the Black Panther Party in cities around the country. Announcing the program in their newspaper Palante, Young Lord Juan Garcia explained: “we, the people, manage to serve the children that the congressmen promised to, that the businessmen write memos about, that the churches say prayers for, that the schools ignore. The YOUNG LORDS PARTY is not promising, writing memos, praying, or ignoring. We’re doing, and we will continue to do–HASTA LA VICTORIA!”

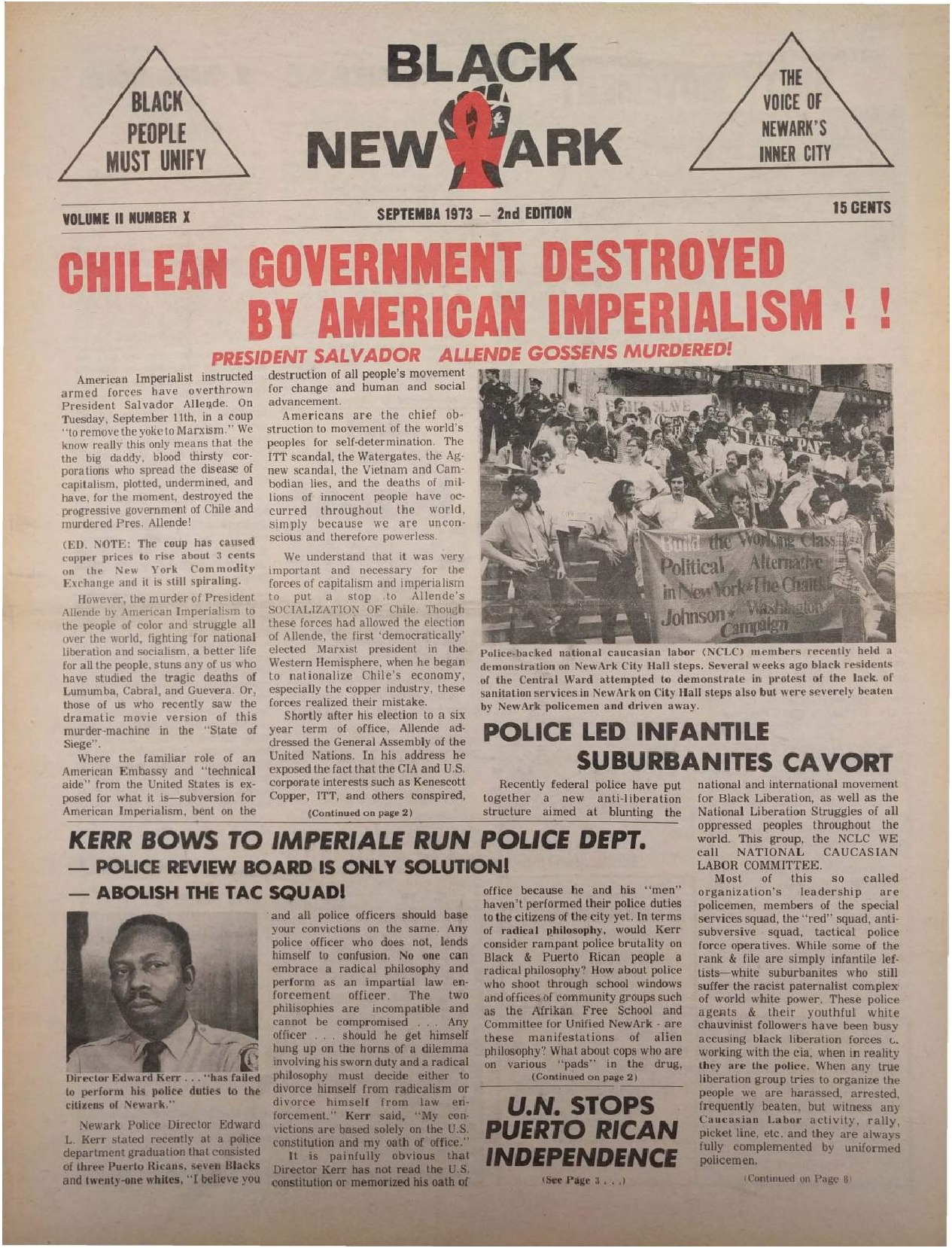

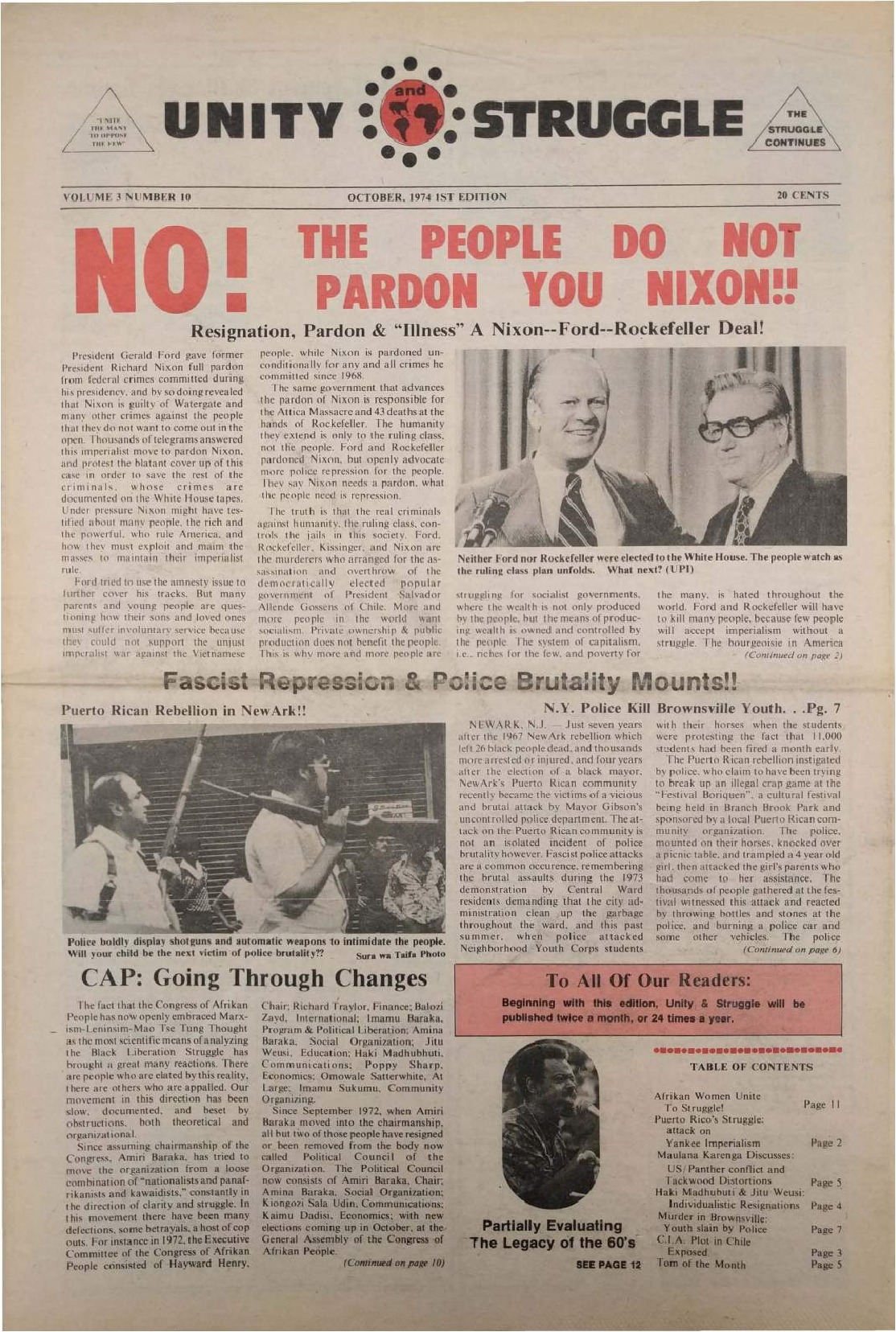

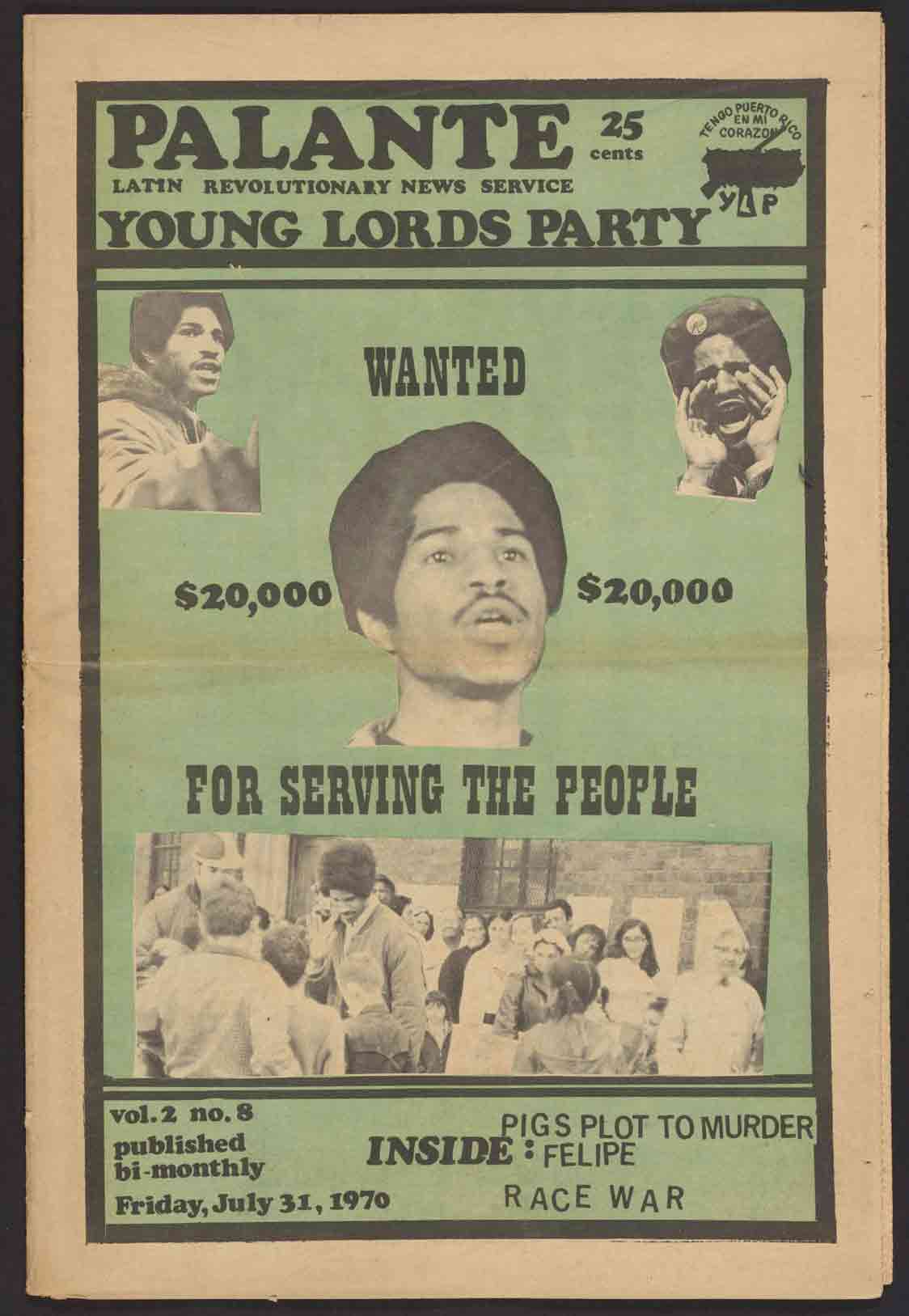

By 1970, the Young Lords had drawn the target of notoriously racist North Ward vigilante-turned politician Anthony Imperiale and the Newark police. During the hotly contested 1970 Newark Teachers Strike that February, the Young Lords joined with community members to help keep open McKinley Street Elementary School in the North Ward, where over half the student body was Puerto Rican. In response, then-Councilman Imperiale and his supporters reportedly showed up with dogs to intimidate students, parents, and community members while blustering that there “would not be any old lords” if the group violated a police order to leave. In early July, Imperiale’s supporters reportedly firebombed the basement of the Young Lords North Ward office and two weeks later, Newark police on horseback and motorcycles attacked Young Lords during the annual Puerto Rican Day parade. “The situation in Newark is extremely tense,” a column in Palante warned that summer. “The city is about to explode.”

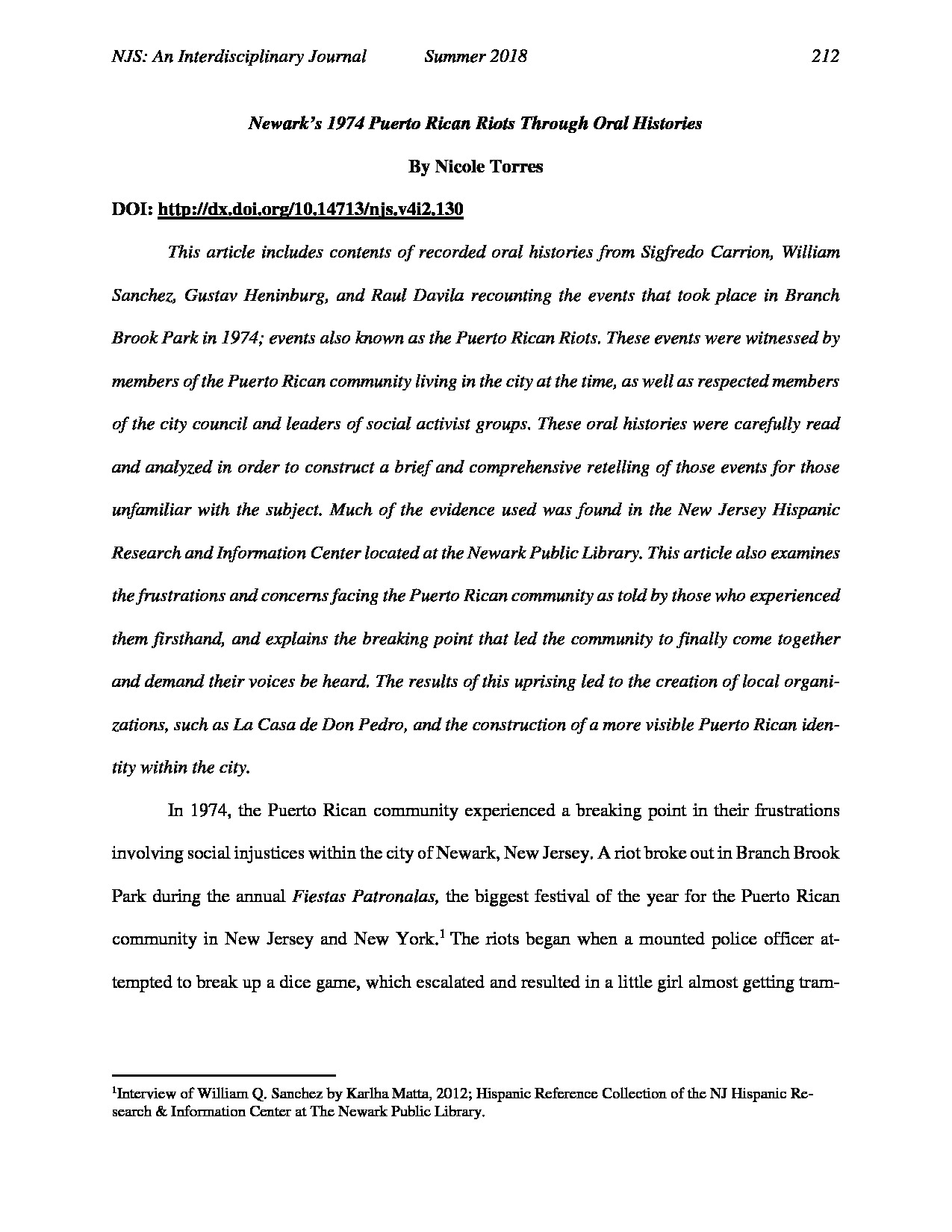

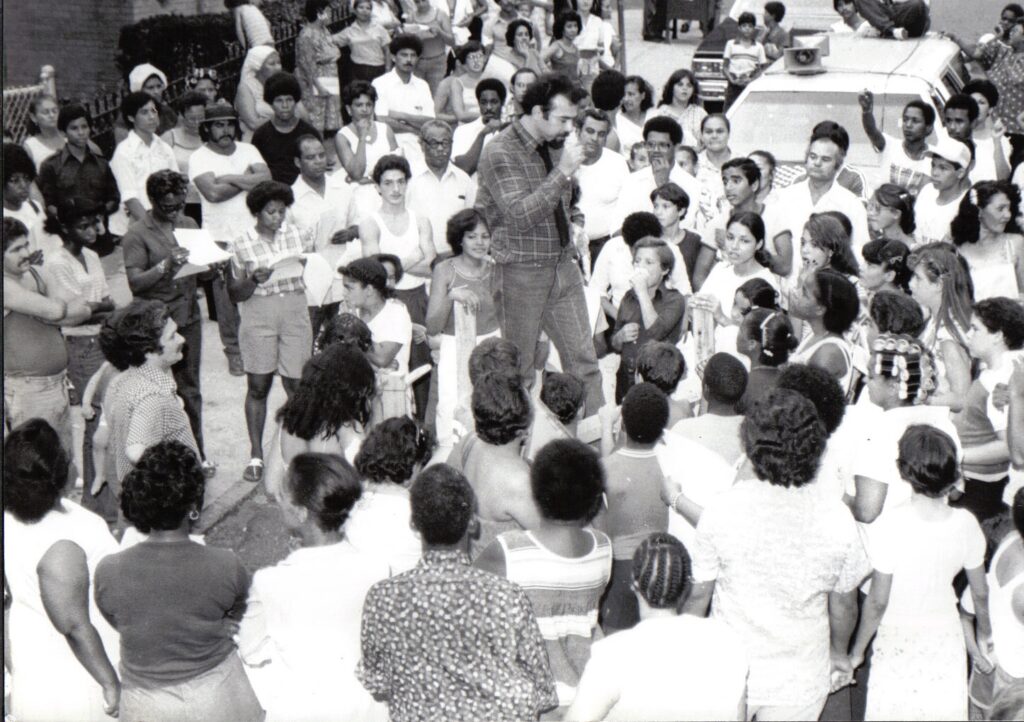

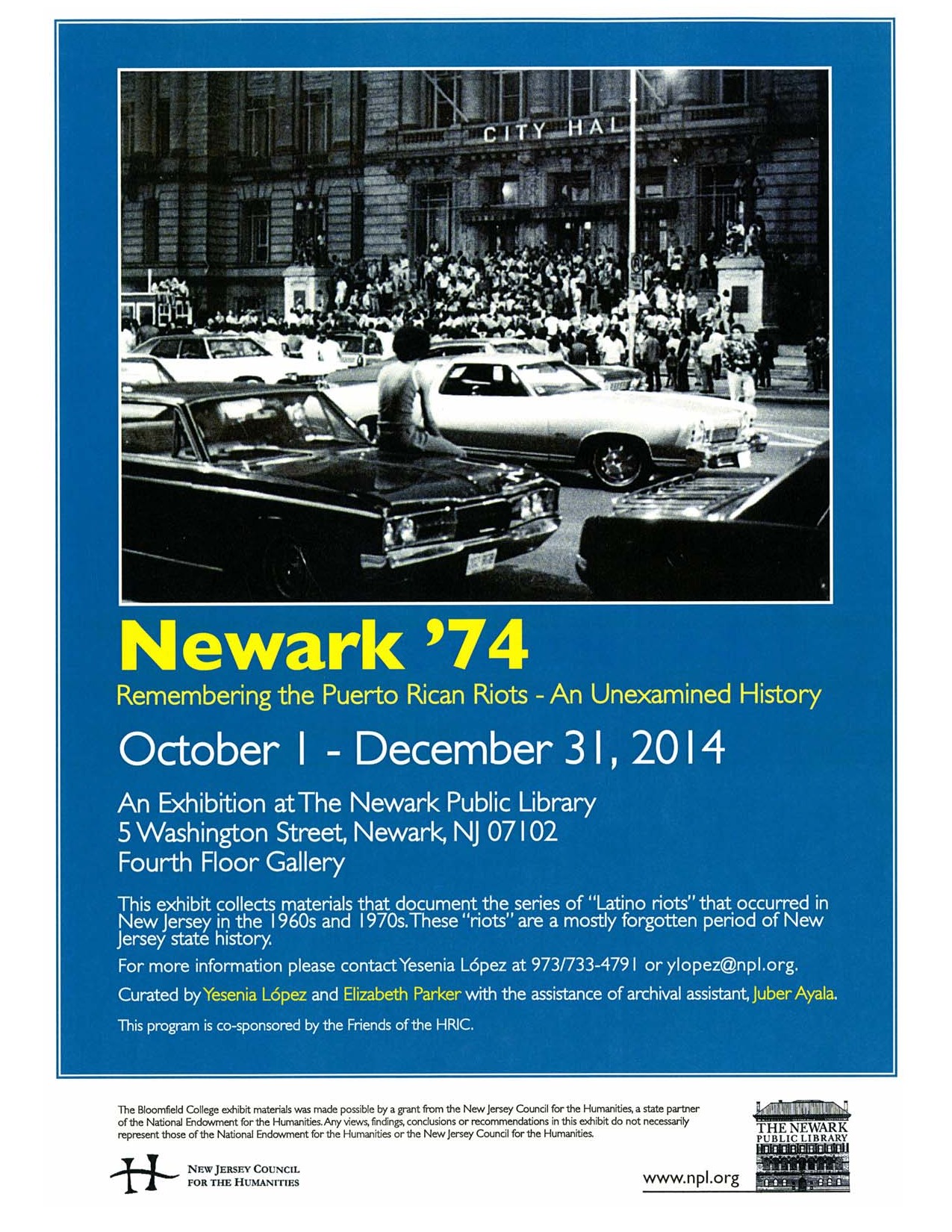

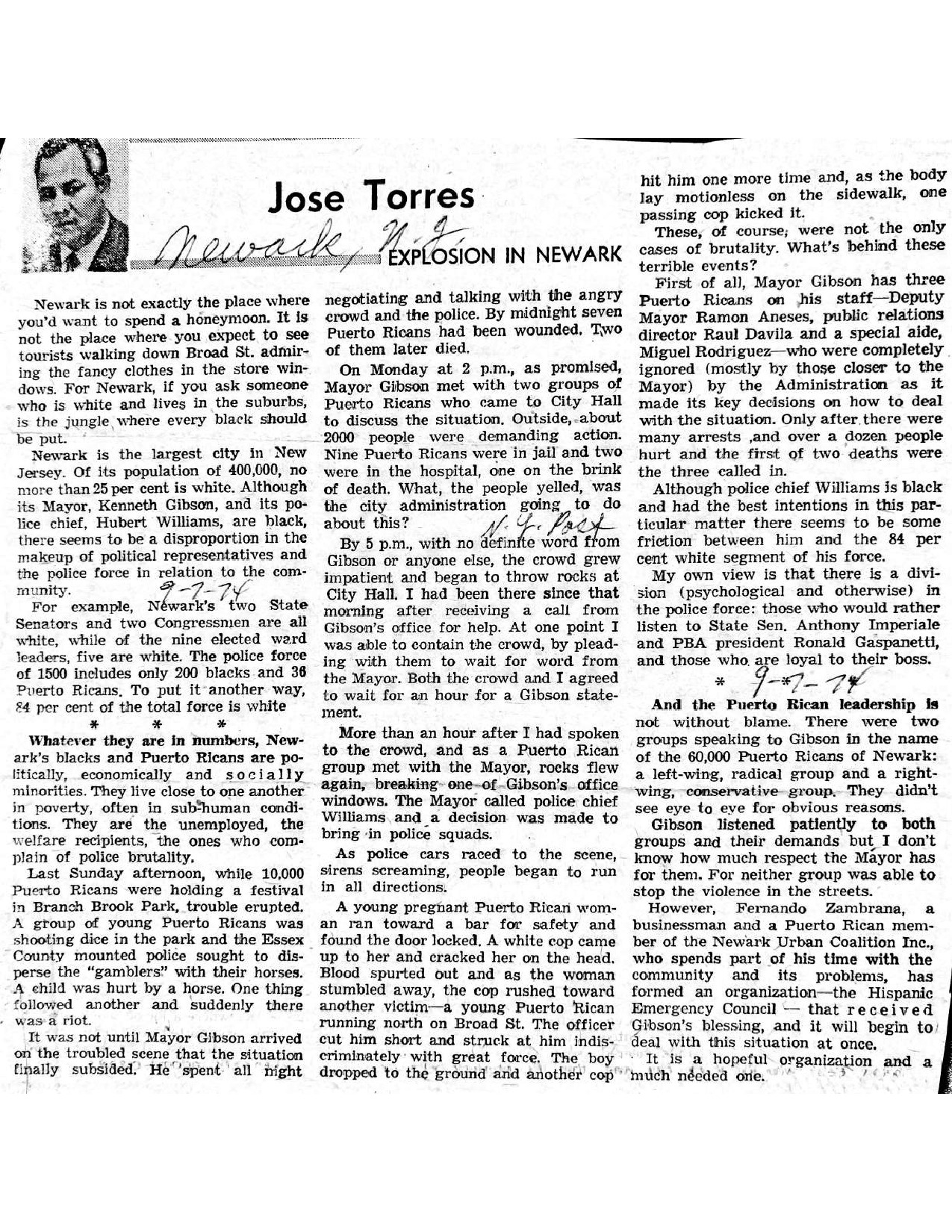

Conditions came to a boiling point under the Ken Gibson Administration. On September 1st of 1974, during the annual La Fiestas Patronales when some 6,000 Puerto Ricans gathered in Branch Brook Park. La Fiestas Patronales is an annual festival celebrated in Puerto Rican communities both in Puerto Rico and abroad that honors Puerto Rican culture. An event that promotes group solidarity, the festival originated as a celebration of each town’s patron saint. As members of the Puerto Rican community played games and ate, mounted police patrolling the festival served as a constant insult and reminder of their oppression in the city. For example, Ramon Rivera had been targeted by the Newark Police Department in the early 1970s with arrests, suppression, and brutality—highlighting a broader pattern of police harassment of the Puerto Rican community. Thus, as police officers on horseback aggressively tried to break up what they believed was a dice game (but may have simply been a game of dominoes) happening at La Fiestas Patronales, a quarrel between the police and community members ended with a little girl being trampled by a horse.

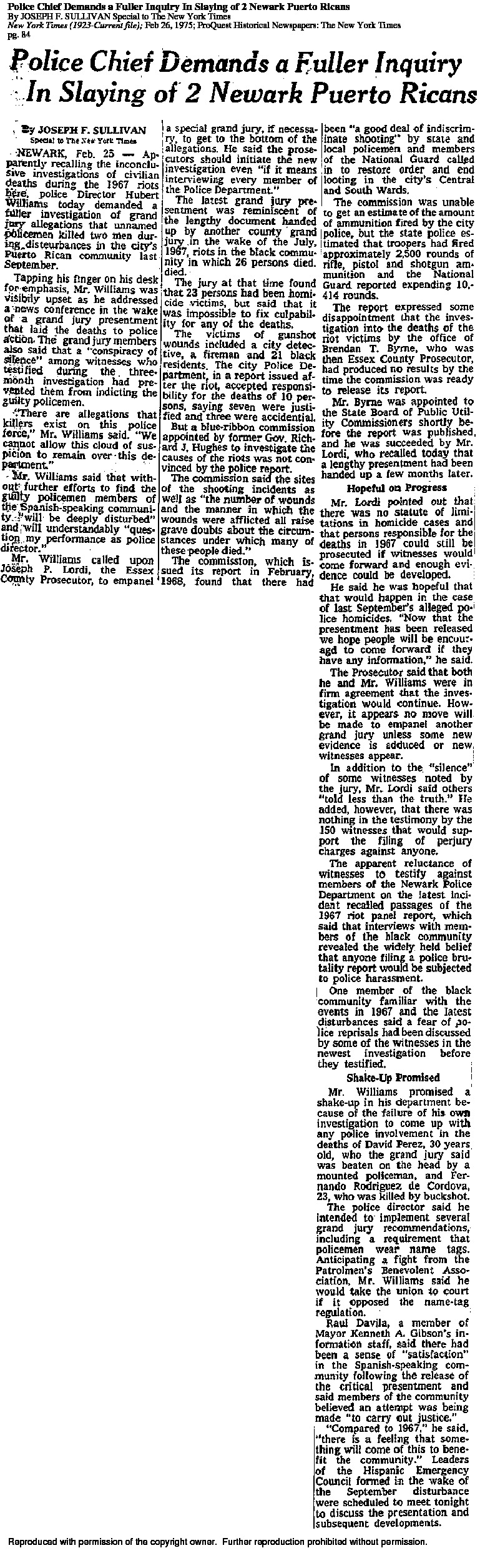

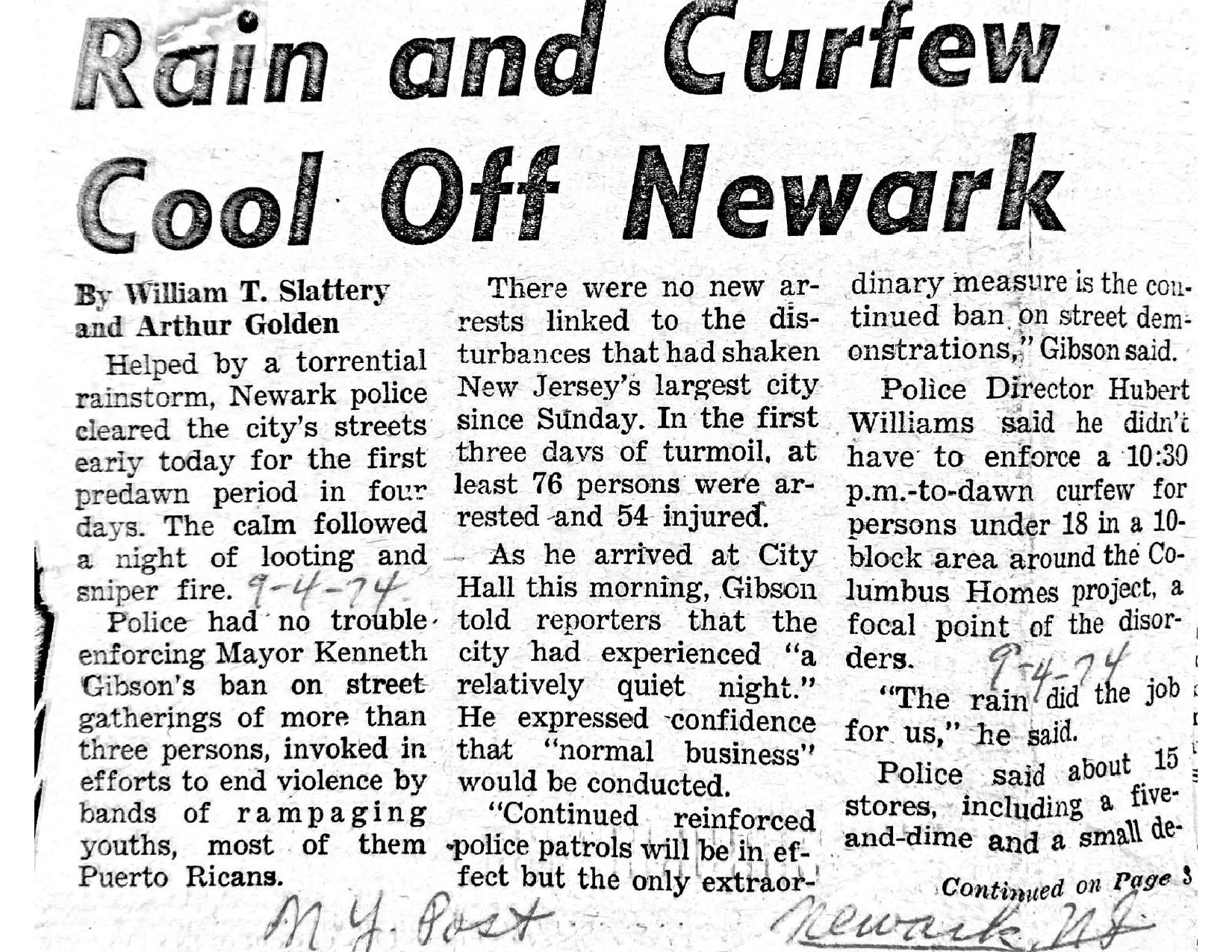

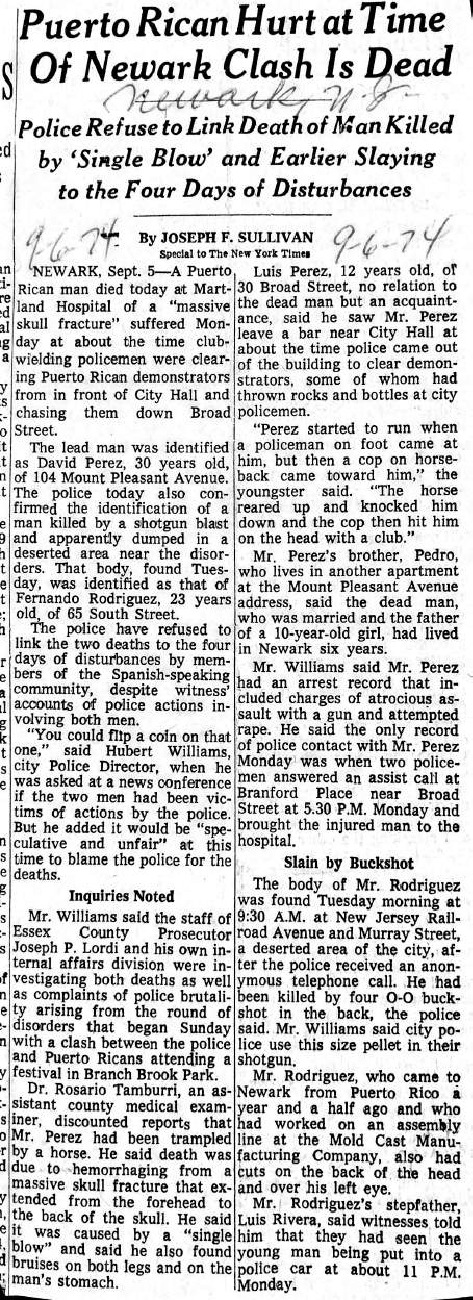

As the crowd of people outraged by the violence of the police swelled, more police armed with nightsticks and shotguns gathered at the park. Although Anthony Imperiale urged the police to clear the park, which would have almost certainly led to massive bloodshed, Mayor Gibson managed to de-escalate the situation. Gibson led a march downtown with members of the Puerto Rican community and called for a delegation of leaders to meet with him at City Hall the next day to discuss plans for dealing with the situation. The next day, however, as angry demonstrators returned to City Hall, police surrounded the crowd and attacked when protestors threw rocks and bottles at the building. The ensuing rebellion would last several more days and included dozens of arrests and the police killings of two more people, Fernando de Cordova and David Perez.

Confrontations between the police and the growing crowd outside City Hall escalated, and another battle was waged inside City Hall. A delegation of leaders from the Puerto Rican community, including the Tony Perez and Jose Rosario, director and presidents (respectively) of FOCUS, Sigfredo Carrion, the leader of the Puerto Rican Socialist Party, and Ramon Rivera, the former head of the Newark Young Lords, went to meet the mayor. Amiri Baraka also joined the delegation as an act of solidarity. Some Puerto Rican leaders were concerned that Baraka’s presence might shift attention away from their demands, which included housing, employment, and healthcare. During negotiations, a rift emerged between the older and younger generations of leaders. This confusion seemed to upset the mayor, who reacted to the demands of the Puerto Rican community by saying he had no control over unemployment. According to Robert Curvin, Gibson even called some of the issues the group wished to discuss “stupid.”

After the rebellion and the negotiations, many leaders in the community recognized the need to form and invest in organizations geared towards providing the services the community needed. One of these organizations, the People’s Committee Against Police Brutality and Repression, was founded by Sigfredo Carrion to address the demands of Newark’s Puerto Rican communities for police reform. In the aftermath of the rebellion, La Casa de Don Pedro, which sought to improve the living conditions of Puerto Ricans in Newark, also increased its profile.

Founded by Ramon Rivera, Alphonso Roman, and several other organizers, the services provided by La Casa de Don Pedro included creating affordable housing, employment training, providing childcare services, and healthcare services. Furthermore, disaffected by their treatment at the hands of Gibson, the Puerto Rican community was vigorously recruited by Stephen Adubato Sr. to sure up his political base in the North Ward as large portions of the Italian community moved out of the city. Over time, with the support of members of the Puerto Rican community Adubato was able to continue his growth as one of the most powerful non-elected political operatives in Newark and New Jersey. Through the support of the Adubato political machine starting in the mid-1970s, Puerto Ricans received more political jobs, appointments, and influence throughout Essex County.

Ultimately the rebellion resulted in the emergence of a more activated Puerto Rican community with more political visibility. Additionally, the rebellion helped to usher in changes to police protocol. The police officer accused of shooting Fernando de Cordova, one of the people killed during the rebellion, was acquitted. It was alleged that his identity could not be verified, even though there was a video recording of the incident. The Gibson Administration mandated that police officers wear name tags and file reports whenever they discharged their weapons. Thus, as the first term of Gibson’s tenure gave way to the second, the political activism of the Puerto Rican community of Newark grew despite their belief that “Under Gibson, we got nothing.” “The only thing that can solve your problem is that well organized, well educated community that can mobilize itself in self-defense,” Rivera later reflected on these years. “It’s people getting together and doing it. All that is done is usually done by a few people who care and take their time and have the commitment to be collective and cooperative.”

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Darrel Enck-Wanzer, The Young Lords: A Reader

Michael Knight, “Young Lords and Police Clash At Newark Puerto Rican March,” New York Times, July 20, 1970

Mark Krasovic, The Newark Frontier: Community Action in the Great Society

Palante Digital Archives, The Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University

Ramon Rivera interview with Vivian Lanzot, October 26, 1988, Newark Public Library

Nicole Torres, “Newark’s 1974 Puerto Rican Riots Through Oral Histories”

“Hispanic Leaders Won’t Back Gibson in County Exec Race,” Star-Ledger, April 10, 1988

Walter H. Waggoner, “Young Lords Get Newark Warning,” New York Times, February 7, 1970

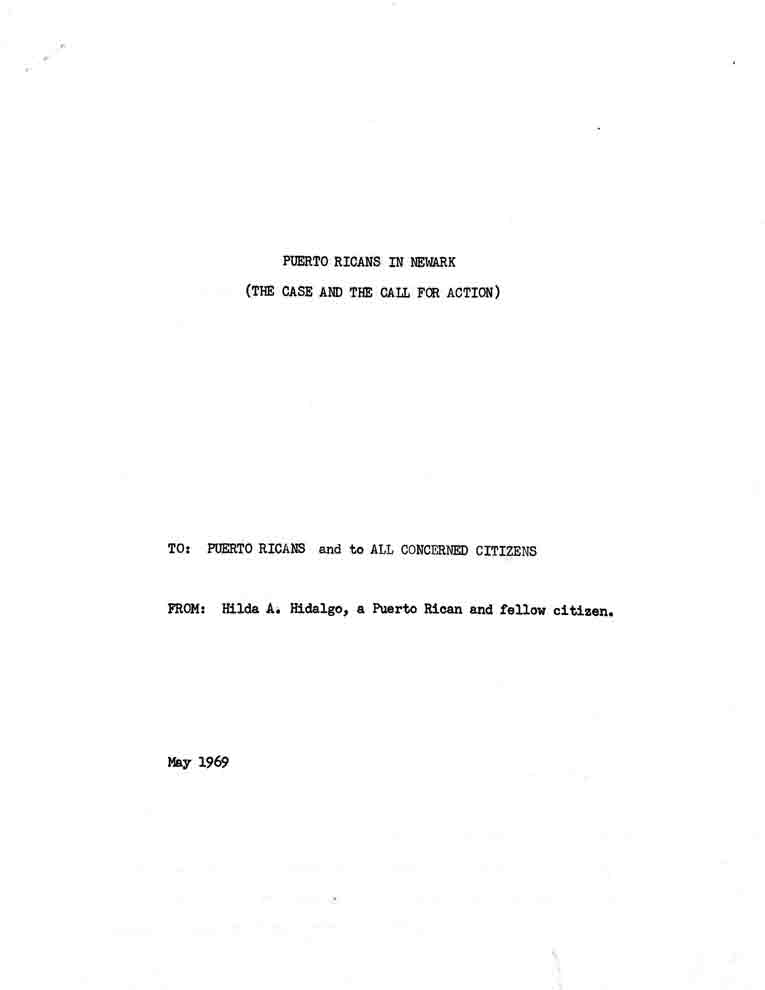

“Puerto Ricans in Newark (The Case and the Call For Action),” by Hilda Hidalgo, May 1969. In this report, Hidalgo analyzes the social, economic, and political conditions facing Puerto Ricans in Newark and recommends a course of action. –Credit: New Jersey Hispanic Research and Information Center

A 1994 interview with organizer and educator Hilda Hidalgo, conducted for the America’s War on Poverty documentary series on PBS. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

A poster advertising the Young Lords Organization’s free breakfast program for children in Newark. The program was modeled after the Black Panther Party’s free breakfast program. –Credit: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Palante, the newspaper of the Young Lords Party, July 31, 1970. See pg. 6-7 for the article “Pigs Declare Race War in Newark, N.J.!” –Credit: The Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives

An article in the New York Times detailing the clash between police and members of the Puerto Rican community in Branch Brook park in September 1974. –Credit: The New York Times

Grizel Ubarry and Miguel Rodriguez discuss the 1974 Puerto Rican Rebellion. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

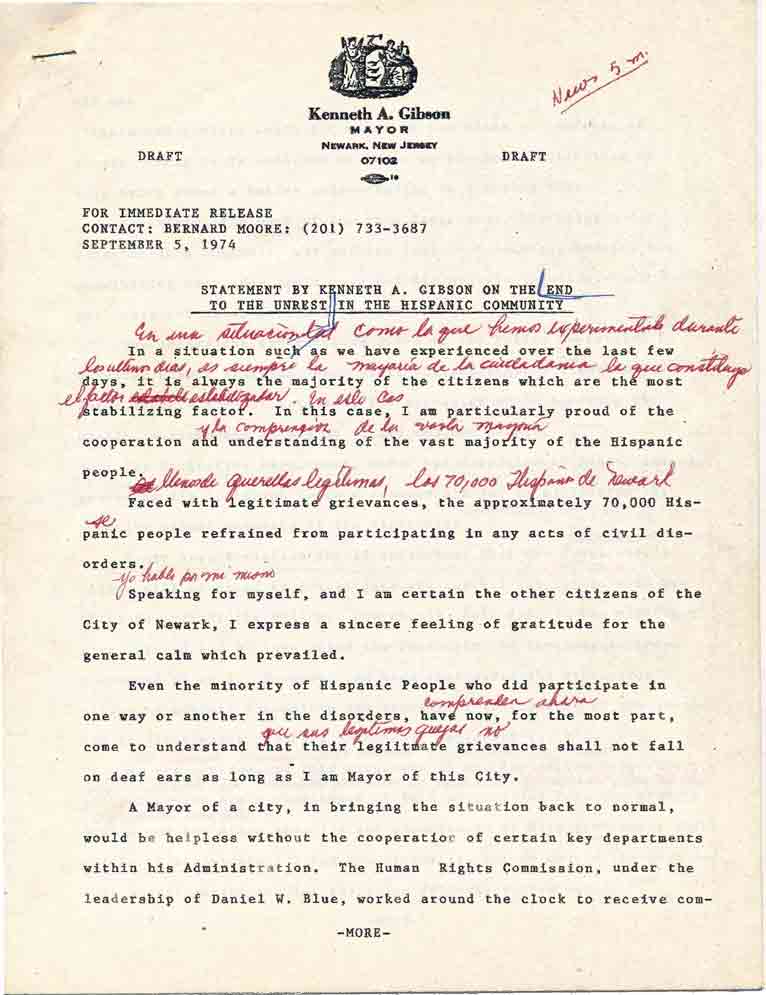

Draft of a statement issued by Mayor Ken Gibson on September 5, 1974 in response to the Puerto Rican Rebellion. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Explore The Archives

Clip from an oral history interview with Newark resident William Sanchez, in which he describes his memories of the 1974 Rebellion. –Credit: New Jersey Hispanic Research and Information Center

A study published in the 1960s by the Newark Human Rights Commission on the experiences of the Puerto Rican community in Newark. The report also includes a map of Puerto Rican neighborhoods in the city. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Report outling the goals and programs of Field Orientation Center for the Underprivileged Spanish (F.O.C.U.S). F.O.C.U.S was founded in 1968 to address the needs of the growing Spanish speaking coomunity in Newark. –Credit: Newark Public Library

This 2018 article explores the 1969 Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention. Lauren O’Brien, “Venceremos! Harambee! A Black and Puerto Rican Union?,” New Jersey Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 4, no. 1 (Winter 2018): 130-146.