Public Housing and the Stella Wright Rent Strike

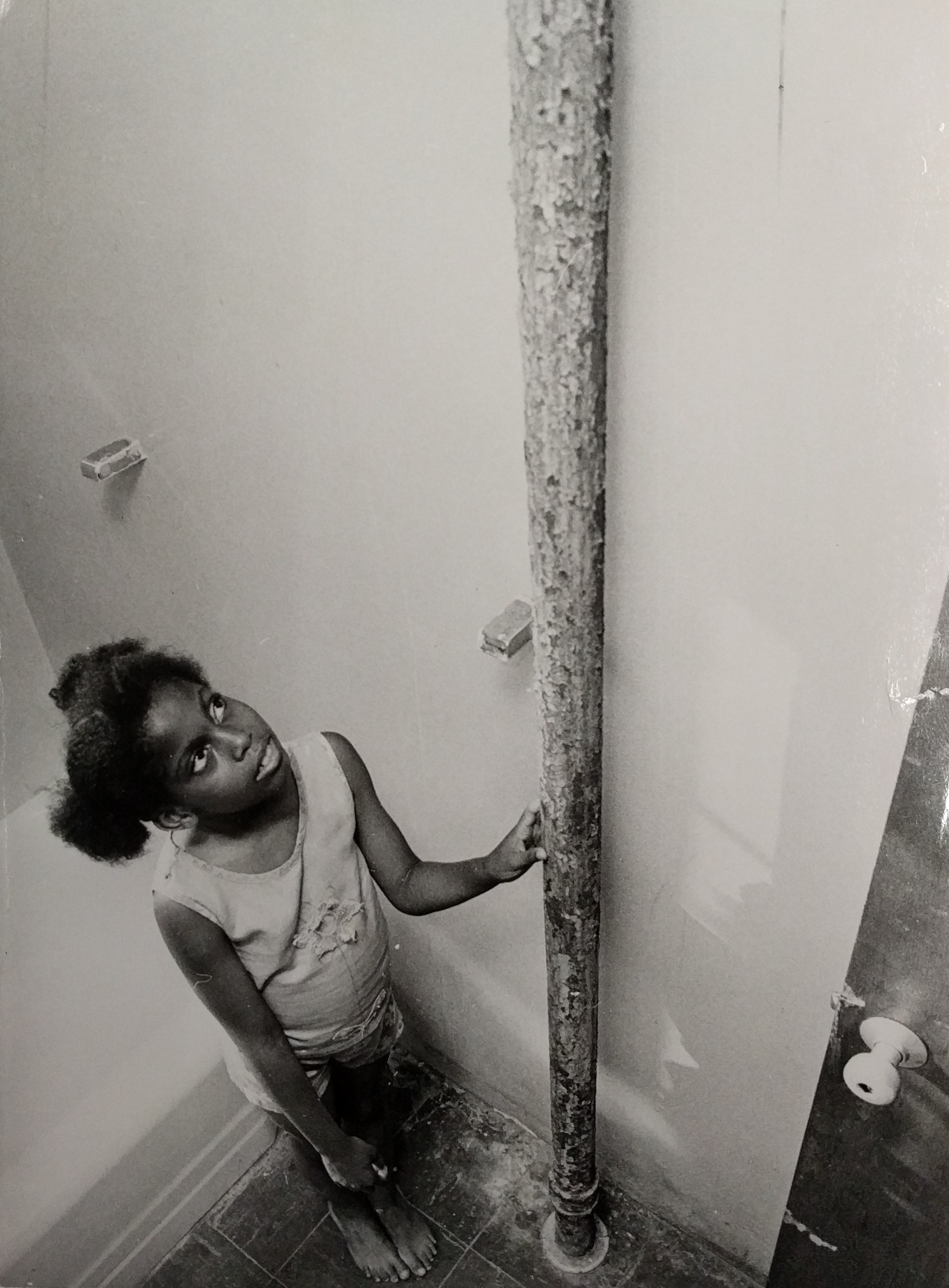

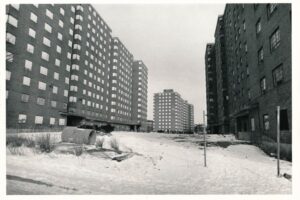

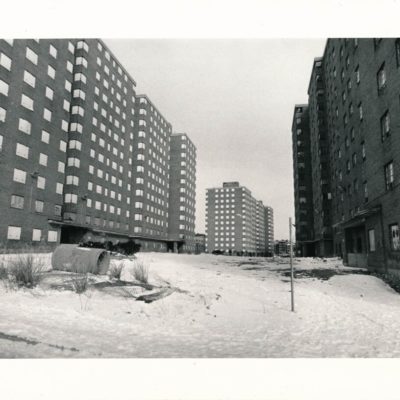

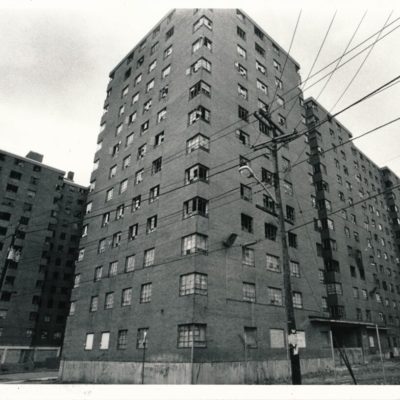

By 1970, public housing conditions in Newark had deteriorated to such an extent that tenants in the city’s public housing projects referred to their buildings as “hell-holes” or “concrete concentration camps.” Though many of Newark’s public housing projects were less than twenty years old, the buildings were poorly constructed and the Newark Housing and Redevelopment Authority (NHRA) put little care into their upkeep and maintenance. “The word to describe what I’ve seen is deplorable,” Bishop John J. Dougherty of the Newark Archdiocese said after touring the Stella Wright Homes project in 1972. “It’s deplorable that people have to live in these conditions because it is dehumanizing and it deprives them of their dignity.” Elevators failed, incinerators poured smoke and soot into hallways and apartments, the roof leaked, rats and roaches were uncontrollable, and there was virtually no security.

The concentration of Black communities in poorly-constructed high-rise public housing projects was a national phenomenon that often concentrated poverty in segregated parts of cities. At the same time, residents of public housing built strong communities and organized for better conditions and collective power. Often led by poor or working-class black women whose political problems tended to be sidelined by other wings of the Black Freedom Movement, rent strikes in both the public and private sectors served as an essential site of organizing for the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO). Founded in 1967, NWRO was led by Johnnie Tillman, a Black woman who developed her organizing skills leading tenant groups in Los Angeles.

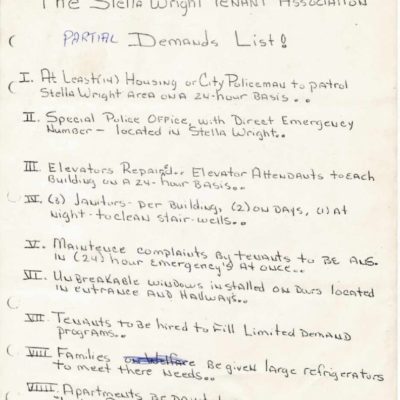

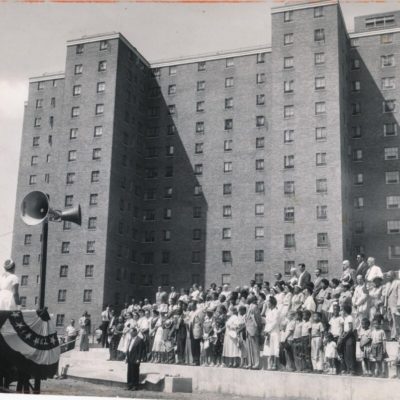

In 1970, the Stella Wright Homes became the epicenter of struggles to improve public housing in Newark. Completed in 1959, the seven 13-story buildings loomed large over Waverly Avenue, and Barclay, Montgomery, and Prince Streets in the Central Ward, housing 1,205 apartment units and nearly 5,000 tenants. As conditions deteriorated in the buildings throughout the 1960s, residents formed tenant organizations, like the Poor and Dissatisfied Tenants Association (an affiliate of the militant National Tenant Organization), to urge the NHA and city government to improve conditions. However, the NHA and city government provided only weak promises of maintenance services—and also announced plans to increase the cost of rent in 1969. Inspired by the Black Power Movement in Newark and the weak responses from City Hall and the NHA, tenant leaders decided that direct action was needed to force the improvement of public housing conditions in Newark.

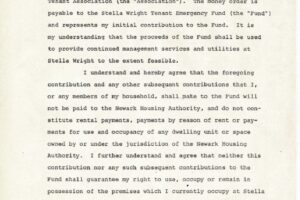

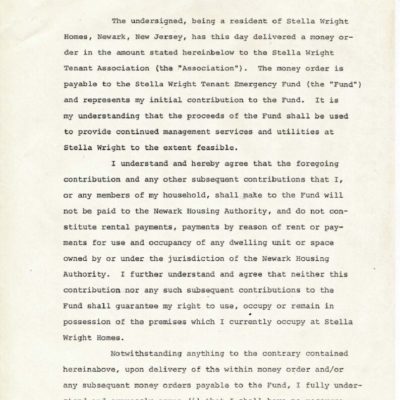

On April 1, 1970, Constance Washington of the PDTA, Stella Wright resident Toby Henry, and Father Thomas Comerford from Queen of Angels Church, declared a city-wide rent strike in public housing to protest living conditions and demand greater representation in policy-making. Though rent strikes had been popularized in the 1960s by Harlem organizer Jesse Gray, and were used in Newark by civil rights organizations like the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) to force slumlords to repair crumbling apartment buildings, they were rarely attempted in public housing. Rent strikes worked by withholding rent payments to landlords until repairs were made to apartment units. Tenants would collectively deposit their rent payments into an escrow account, and landlords could collect the back rent once repairs were completed. As the 1970 rent strike got underway in Newark, tenant leaders in each building collected rent from their fellow strikers and deposited it in an account managed by the Newark Legal Services Project. By November 1970, the strike spread from Stella Wright and the Scudder Homes to include 14 other projects throughout the city.

The Stella Wright Tenants Association quickly emerged amongst a network of tenant organizations as the leading force of the rent strikes, but worked cooperatively with other groups like the PDTA and Newark Public Housing Joint Tenants Association. Led by Toby Henry, the SWTA’s 25-year-old president who had spent time in juvenile institutions before starting his own record company and becoming an antipoverty activist, along with vice-president Juanita Short, and tenants Ed Satterfield and Rev. Tom Comerford, the Stella Wright Tenants Association had the most dedicated organizers and greatest participation in the strike, with more than half of the projects’ residents participating. They also had the support of members of the Archdiocese of Newark, who backed Rev. Comerford’s involvement as part of his ministry at Stella Wright.

The rent strikers scored an early victory one month in, when a superior court judge issued a temporary restraining order that stopped the NHA from evicting them. Although the NHA tried to paint tenants as “riding the back of the rent strike” in order to live rent-free, Judge Ward Herbert ruled that eviction violated the rights of tenants for whom public housing was “a last resort.” That fall, health inspectors found over 2,000 violations in the Columbus Homes, as city and federal officials pressured the NHA to conduct inspections and make repairs. To tenants, though, the inspections and minor repairs were like putting a bandage over a gaping wound. By the end of 1970, nonpayment of rents totaled over $875,000, as nearly 100% of the monthly rent roll was being withheld. The lack of revenue was crippling to the NHA’s ability to meet operating costs and utility payments.

As the rent strike dragged on, the NHA dug in its heels against proposals from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to reform the administration’s structure and policies. In the summer of 1971, the Gibson administration mediated a compromise between the agencies which led to NHA director Joseph Sivolella being replaced by Robert Notte and Gibson ally Pearl Beatty being appointed to the NHA board. These maneuvers, however, did little to improve living conditions for the tenants.

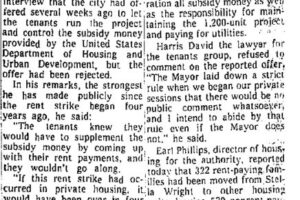

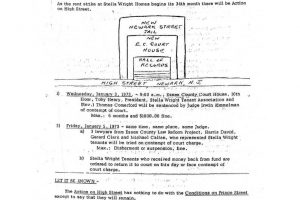

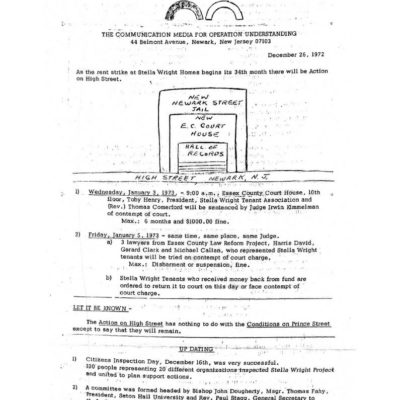

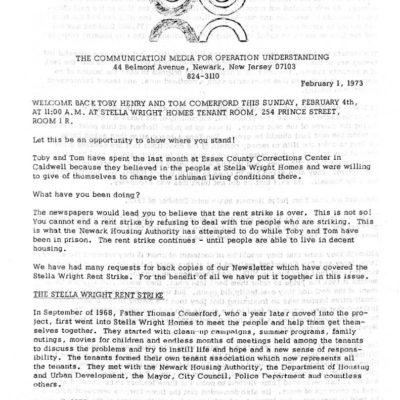

From 1972-1973, the NHA battled the rent strikers in court in attempts to end the strike. By 1972, the NHA had lost nearly $2 million in rent, and filed suits against the Stella Wright Tenants Association over the rent payments held in escrow. Rather than turn over $94,000 collected by the SWTA to the NHA, who had failed to make necessary repairs, Toby Henry and Rev. Comerford withdrew the funds and redistributed the money to the tenants who had deposited it. For this act, Henry and Comerford were held in contempt of court and sentenced to 45 days in jail. The trial drew the media spotlight, and celebrities like Bill Cosby, Bill Withers, and Erma Franklin showed up in court to lend their support to the rent strikers. “The housing authority,” Greater Newark Urban Coalition president Gus Heningburg argued, “made a political decision to destroy the tenant leadership at Stella Wright…They figured it they could break Toby Henry, then they could break the strike. Well, it didn’t work. Toby Henry went to jail. They made a martyr out of him.”

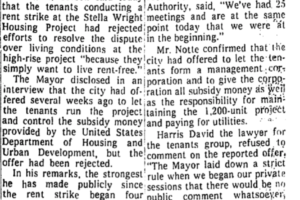

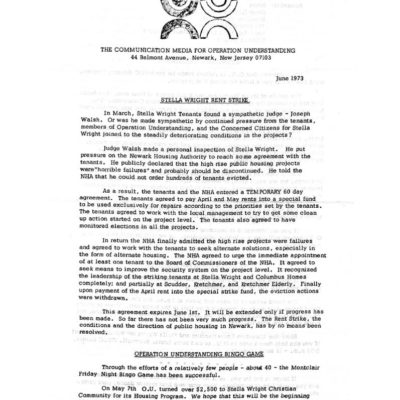

In March 1973, the rent strikers were back in court, as the NHA brought eviction suits against 11,000 tenants (25% of Newark’s public housing population) for non-payment of rent. Although the tenants and NHA reached a 60-day interim settlement, the agreement fell through just weeks later, and the sides were back in court. In November, as the NHA brought the first eviction suits to trial, Judge Joseph Walsh issued a major victory for the rent strike. Ruling that Stella Wright was “uninhabitable,” Judge Walsh refused to order any evictions and granted an 80% reduction of past and future rents. Furthermore, the judge recommended that if conditions could not be improved, Stella Wright should be torn down.

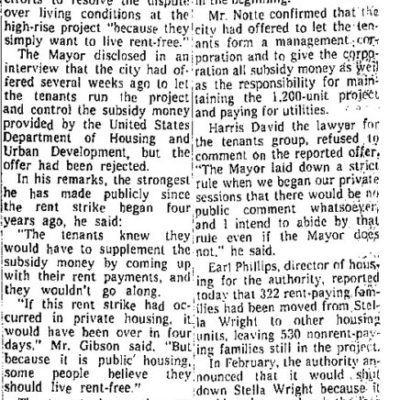

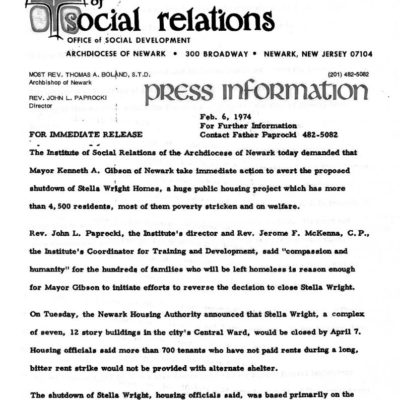

When the NHA announced plans to actually close Stella Wright in early 1974, however, a crisis point was reached. With 11,000 tenants withholding $6.5 million in rent, the NHA was on the cusp of bankruptcy, and moved to shut down Stella Wright by April 15, 1974. Although some tenant leaders initially welcomed the prospect, the lack of affordable housing in Newark meant that if Stella Wright actually closed, more than 700 families would essentially be left homeless. Unlike the more well-known Pruitt-Igoe public housing controversy in St. Louis, tenants in Newark would have no place to go, with a city-wide vacancy rate of less than 3%. While some tenants were relocated to other projects, others stayed, insisting on running the project themselves. Although tenants obtained a court order postponing the project’s closing, a long-term solution needed to be found.

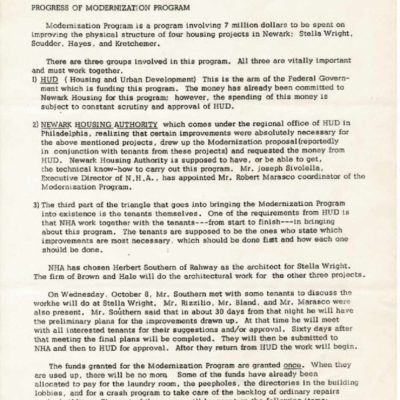

Toby Henry approached Gus Heningburg to negotiate with the NHA, city officials, and HUD on behalf of the tenants. After weeks of long and contentious negotiations, an agreement was reached and the rent strike was ended in July 1974. Called a “monumental accomplishment” by Judge Frederick Lacey, the terms of the agreement included: tenant management of Stella Wright; a seat on the NHA Board of Commissioners reserved for a high-rise public housing tenant; a Citizens Task Force to oversee the agreement; tenant payment of back rent from February 1973 onward; NHA pledge to continue operation of Stella Wright with maximum possible services; dismissal of lawsuits against tenants; and $1.3 million in HUD funding for the NHA to make improvements at Stella Wright. As Essex-Newark Legal Services attorney Harris David argued, the tenant management of Stella Wright was not only a way to empower and employ residents of Newark public housing, but also a “vehicle for the building and regeneration of community.”

Though material conditions improved only slightly in the months following the agreement, the Stella Wright Tenants Association and their allies proved that organized tenant action could force action from city and federal forces and promote community control over public institutions. Rev. Comerford called the Stella Wright Rent Strike “a struggle to moralize the priorities of our country. A struggle to prevent the abandonment of the cities. To protect the human rights of minority groups.” The Stella Wright Rent Strike was the longest public housing rent strike in the nation’s history, and demonstrated the power of tenants in the era of Black Power.

Through their work on the Stella Wright Rent Strike, Newark’s tenant organizers fought for decent affordable housing as a civil and human right. The Stella Wright Homes operated using the tenant management system until the 1990s when, like the whole generation of high-rise public housing buildings, it was labeled a failure and slated for demolition by the NHA. HUD moved towards a privatized system with federal subsidies for poor tenants to enable them to rent in the private market. Over the next few decades, NHA destroyed over seven thousand units of housing, which it never replaced–thus, access to low-income housing remains a critical issue in Newark into the present.

References:

Harris David, “The Settlement of The Newark Public Housing Rent Strike: The Tenants Take Control”

Arnold R Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago 1940-1960

Clarence Lang, Grassroots at the Gateway: Class Politics and Black Freedom Struggle in St. Louis, 1936-75

Julia Rabig, The Fixers: Devolution, Development, and Civil Society in Newark, 1960-1990

The National Urban Coalition, “The Stella Wright Rent Strike and the Greater Newark Urban Coalition”

Rhonda Y. Williams, Fighting for Respect: Low-Income Black Women’s Struggles against Urban Inequality in Post-Depression Baltimore

Clip from an interview with United Community Corporation (UCC) member Mary Smith, in which she describes public housing conditions and becoming involved with organizing tenants in Newark’s public housing projects. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

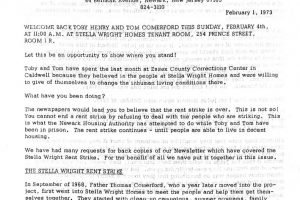

A press release issued on June 22, 1970 by the Stella Wright Tenant Association, describing the background of the rent strikes. –Credit: Dennis Westbrooks Collection

A list of low rent housing projects in Newark, compiled by G. Cahalan in July 1967. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Eight-year-old Evelyn Ormond looks up at the crumbling wall in the bathroom of her family’s apartment in the Stella Wright Homes public housing project in 1972. In April 1970, tenants in the high-rise building began a rent strike to force building repairs that lasted four years.

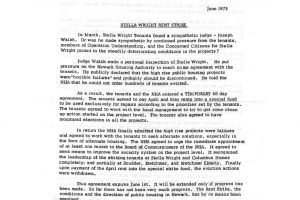

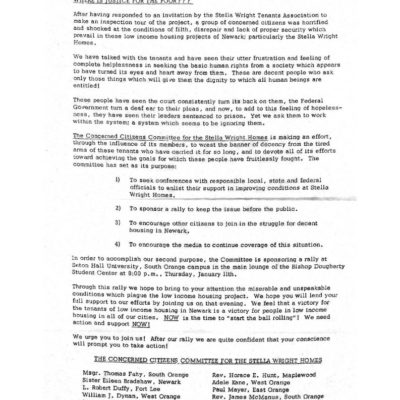

Press release on the Stella Wright Rent Strike, issued on April 15, 1971 by Operation Understanding’s Concerned Citizens Committee for the Stella Wright Homes. –Credit: Seton Hall University Libraries

Greater Newark Urban Coalition president Gustav Heningburg describes the origins and impacts of the Stella Wright Rent Strike in Newark. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

Transcript of court proceedings from the trial of Toby Henry and Thomas Comerford, who were found guilty of contempt of court and sentenced to 45 days during the rent strike. –Credit: Seton Hall University Libraries

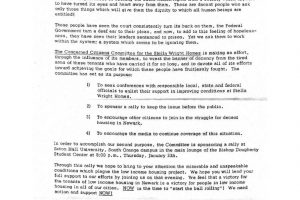

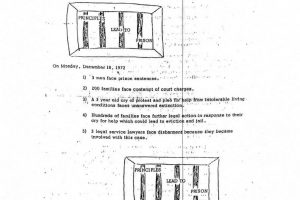

A summary of the progress and developments following the temporary settlement agreement reached during the Stella Wright Rent Strike. The document also includes a copy of the 60-day agreement. — Credit: Seton Hall University Libraries

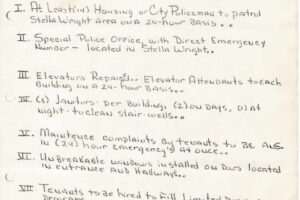

Handbook for residents of the Stella Wright Homes, issued in 1975 following the settlement of the Stella Wright Rent Strike. The handbook includes a copy of the 1974 agreement, as well as diagrams of the organizational structure of the Stella Wright Tenant Association.

EXPLORE THE ARCHIVES