Marion Kidd

Marion Kidd was born in Newark on October 12, 1928 and later raised her eight children in the city. Kidd’s experiences with injustice in the city and county welfare departments as a single mother of eight led her to take action and organize around issues of welfare rights and economic justice in Newark.

Kidd became involved with the United Community Corporation (UCC), Newark’s Community Action Agency funded by the War on Poverty when it was formed in 1965. Kidd served as a representative from Area Board #3 (People’s Action Group), which served the city’s South Ward. As a member of Area Board #3, Kidd was the chairperson of the Welfare Committee, a group of mothers who organized for economic and social justice for welfare recipients in Newark and beyond. The women protested local stores that cheated them on groceries, caseworkers that worked in cahoots with the stores to trap the women in debt, mistreatment by overbearing and intrusive caseworkers, and the system of welfare itself that curbed economic uplift.

As chair of the Welfare Committee, Kidd was instrumental in establishing the consumer buying club, which organized women to collectively buy their groceries from wholesalers to save money and sidestep the cheating practices of local grocers. Kidd and the Welfare Committee’s efforts to establish the buying club were documented in the short documentary film With No One to Help Us, which was produced by Project Head Start with funding from the Office of Economic Opportunity.

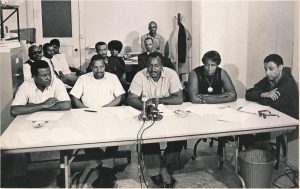

During the 1967 rebellion, Kidd was one of several community leaders that met to advocate for Newark’s Black communities and to publicly issue a series of demands to city and state officials. Kidd herself was nearly killed during the rebellion when National Guardsmen fired into her apartment on Fairmount Avenue, leaving bullet holes in the wall of her bedroom.

As a result of her work on the Welfare Committee, Kidd decided to organize a chapter of George Wiley’s National Welfare Rights Organization in Newark. She assembled a group of women, including Juliet Grant, Alma Perry, and Nettie Duncan, and many more who became leaders for equity and fair play for welfare recipients.

In addition to her work with the United Community Corporation and Welfare Rights, Kidd was also vice president of the Essex-Newark Legal Services Project and served in the Urban League of Essex County and The Mayor’s Manpower Planning Council. “She was one of the original Community Organizers,” a member of her church later wrote of Kidd. “She quietly spoke boldly to equip and educate people to get involved with the events that would shape and affect their everyday lives.”

References:

Recollections of Junius Williams

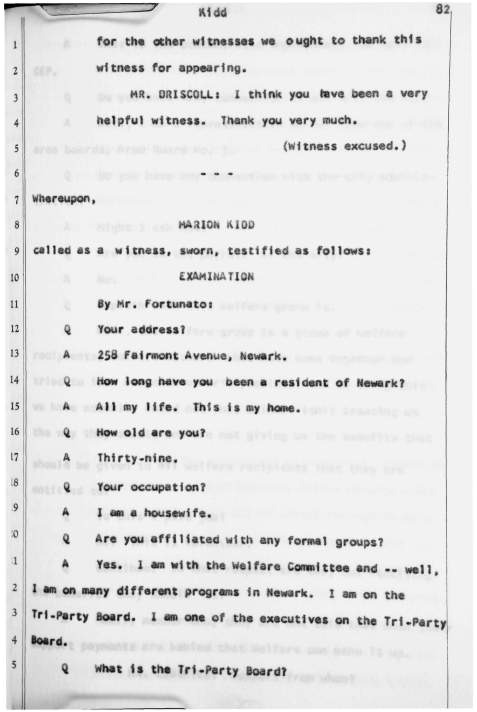

Testimony of Marion Kidd before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Oct. 17, 1967

Compilation of clips from the film “With No One to Help Us,” with Marion Kidd narrating the efforts of the Welfare Committee to establish a consumer buying club. — Credit: Prelinger Archives

Testimony of Marion Kidd before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder on October 17, 1967. — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository

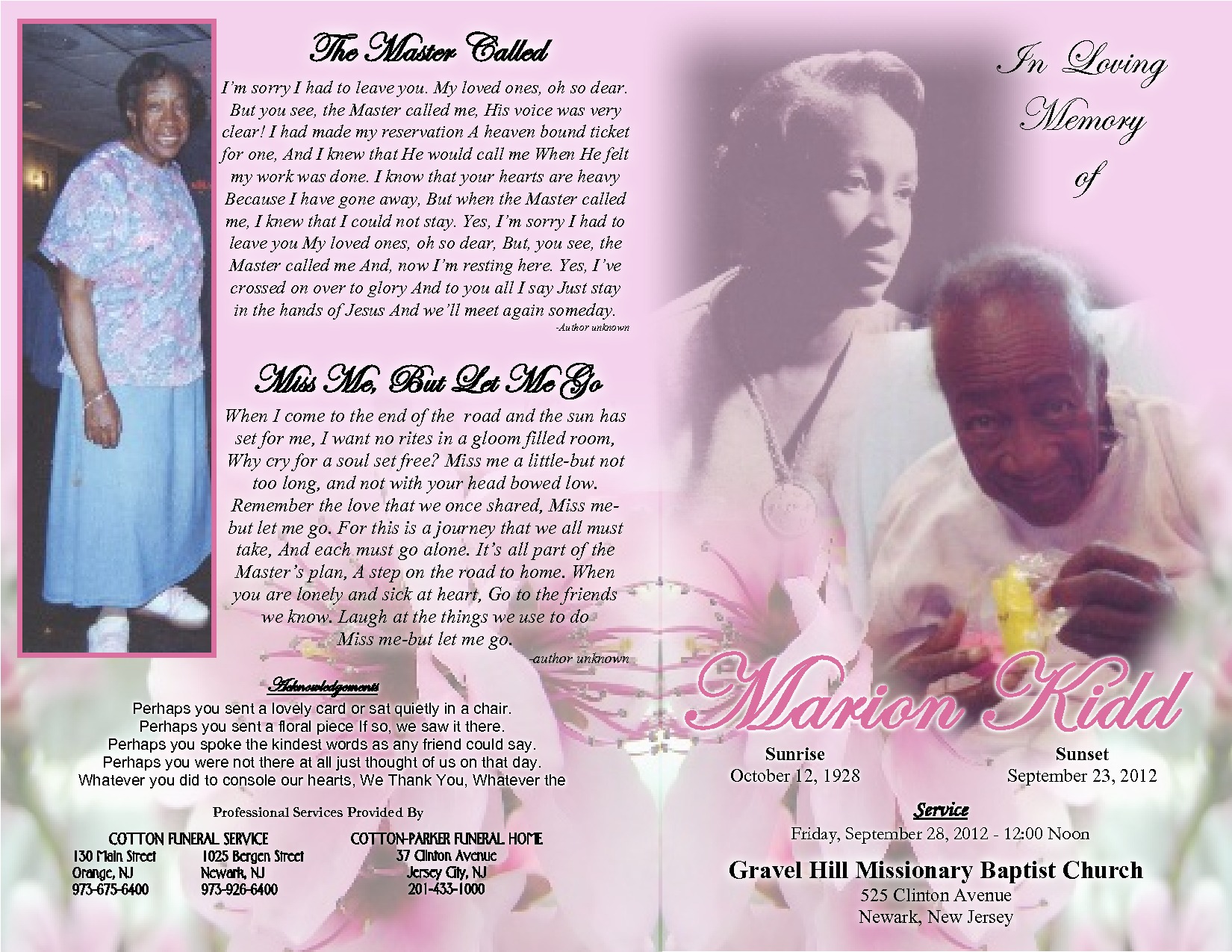

Program for the homegoing services of Marion Kidd, which were held at Gravel Hill Missionary Baptist Church on September 28, 2012. — Credit: Gravel Hill Missionary Baptist Church