Harry Wheeler

Harry Wheeler was born and raised in Newark, where he went to school and later became a teacher at Hawthorne Avenue School. As a young teacher, Wheeler played an active role in the campaign to elect Newark’s first Black city councilman, Irvine Turner, in 1954. Wheeler was described as a “bright young politico who became a brilliant urban strategist coming out of the Turner victory.”

As such, Wheeler was ambitious. He campaigned for Hugh Addonizio in 1962 and upon Addonizio’s victory, Harry asked to be appointed Business Administrator. Unkind words were exchanged upon the Mayor’s refusal to appoint Wheeler, who was offered a job of far lesser importance. Eventually, Wheeler returned to teaching and was implicated in a minor scandal involving missing milk money for the children at Hawthorne Avenue School. Though many people suspect this was a set-up by Mayor Addonizio, Wheeler never really recovered from the accusation, although no charges were ever filed.

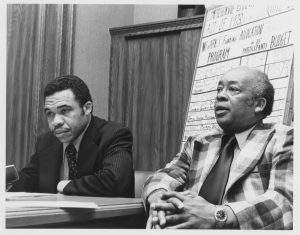

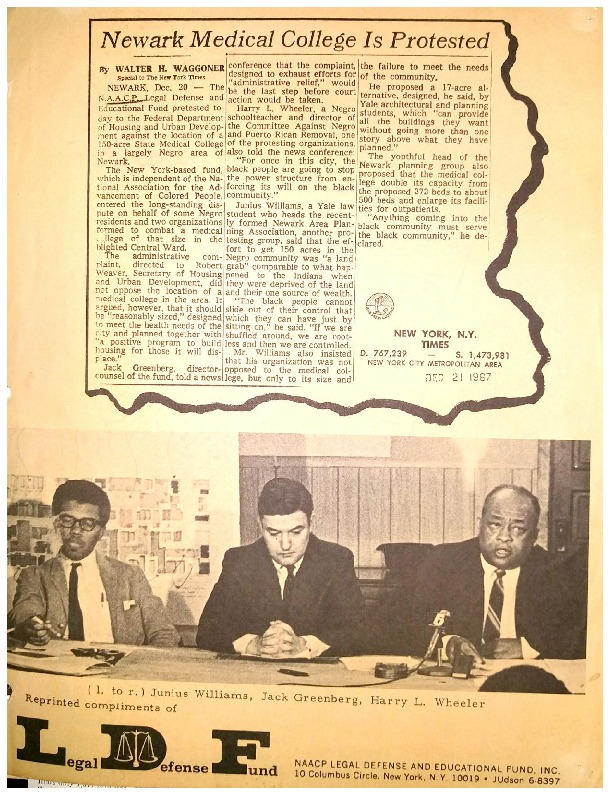

Harry Wheeler was a fighter. As coordinator of the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal in 1967, Wheeler played a central role in community struggles against plans to build the New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry in the Central Ward. The original plans called for a 200-acre campus that would have displaced 20,000 residents of the predominantly Black neighborhood. After months of meetings, protests, and the 1967 rebellion, when it finally came time to negotiate the terms of the school’s development with local, state, and federal officials, Wheeler was one of the leaders chosen to represent the Central Ward community. Wheeler, Junius Williams, Louise Epperson, and Duke Moore finally reached an agreement with the medical school and government officials that reduced the school’s size and included assurances of employment, relocation, housing, and healthcare provisions for the community. Wheeler referred to this agreement as the ‘Magna Carta of Newark’ and proclaimed that, ‘for the first time, the people had a voice in making policy that affected them.’

While involved in the Medical School Fight, Wheeler was also invited to join the United Brothers, a new Black political organization formed by Amiri Baraka, Harold Wilson, and John Bugg. In June 1968, Wheeler chaired the Newark Black Political Convention, which was organized by the United Brothers, to win two seats on the City Council in the November special elections. To Wheeler, the purpose of the convention was ‘the development of a platform on important city issues.’ Although both nominees, Ted Pinckney and Donald Tucker, were unsuccessful in their campaigns, the Convention served as a “dress rehearsal” for the 1970 Mayoral election.

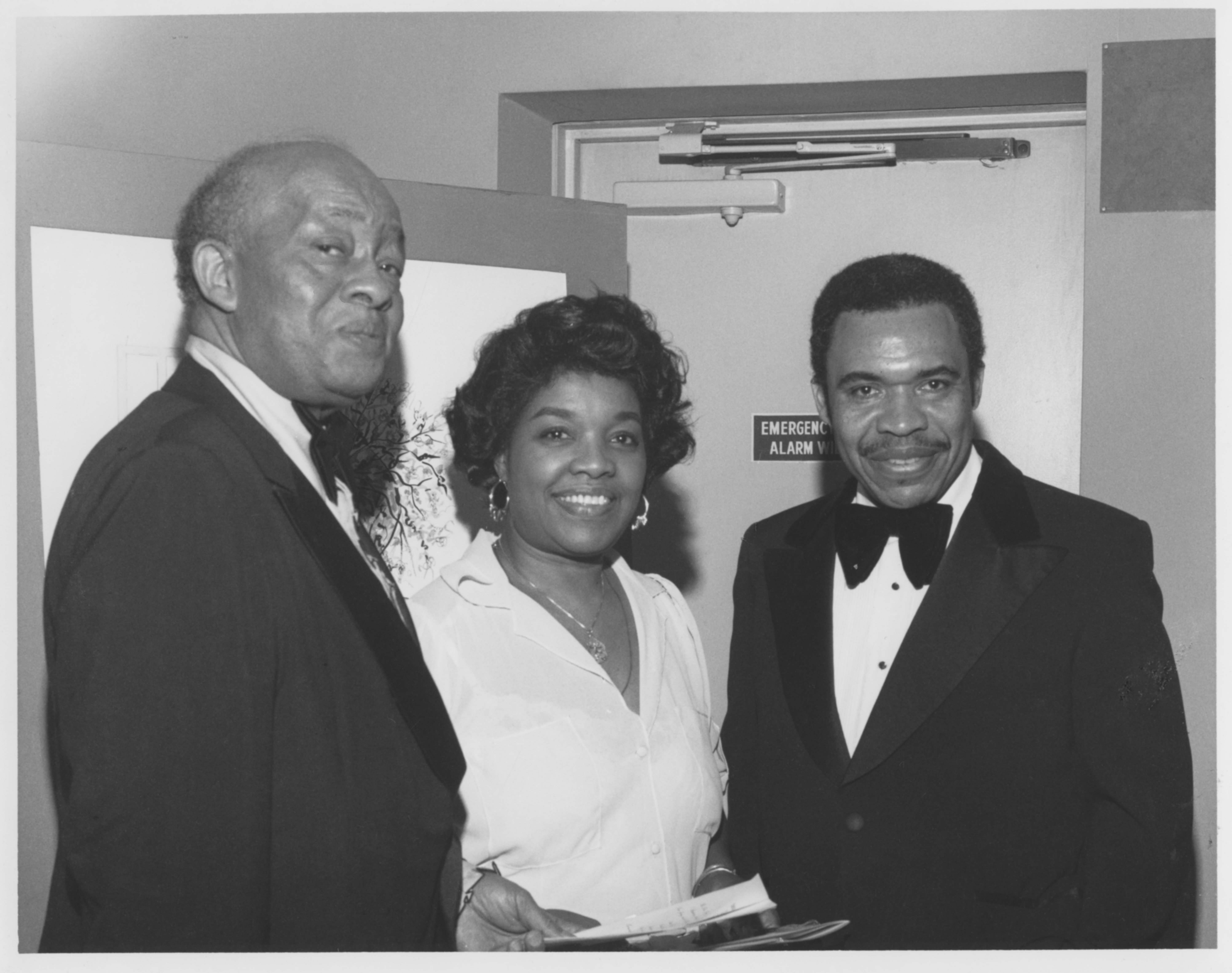

Shortly after the 1968 Convention, Wheeler took a job in Washington, D.C. as coordinator of a program for the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). Though the position was a good opportunity for Wheeler, it took him away from Newark and dashed his political aspirations for the 1970 Mayoral election. Though Ken Gibson became the nominee of the Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention in 1969, Wheeler decided to run on his own, only to pull out of the race at the eleventh hour. Had he not taken the job in Washington, many in Newark felt that Wheeler could have been the “Community’s Choice” for Mayor in 1970. “Harry Wheeler should have been the mayor,” Eulis “Honey” Ward later said. “We were rigging for Harry Wheeler. But Harry went and took the job in Washington.” When Gibson was elected, Wheeler was appointed as Director of Manpower, a job training program, and often served as the Mayor’s representative at speaking engagements.

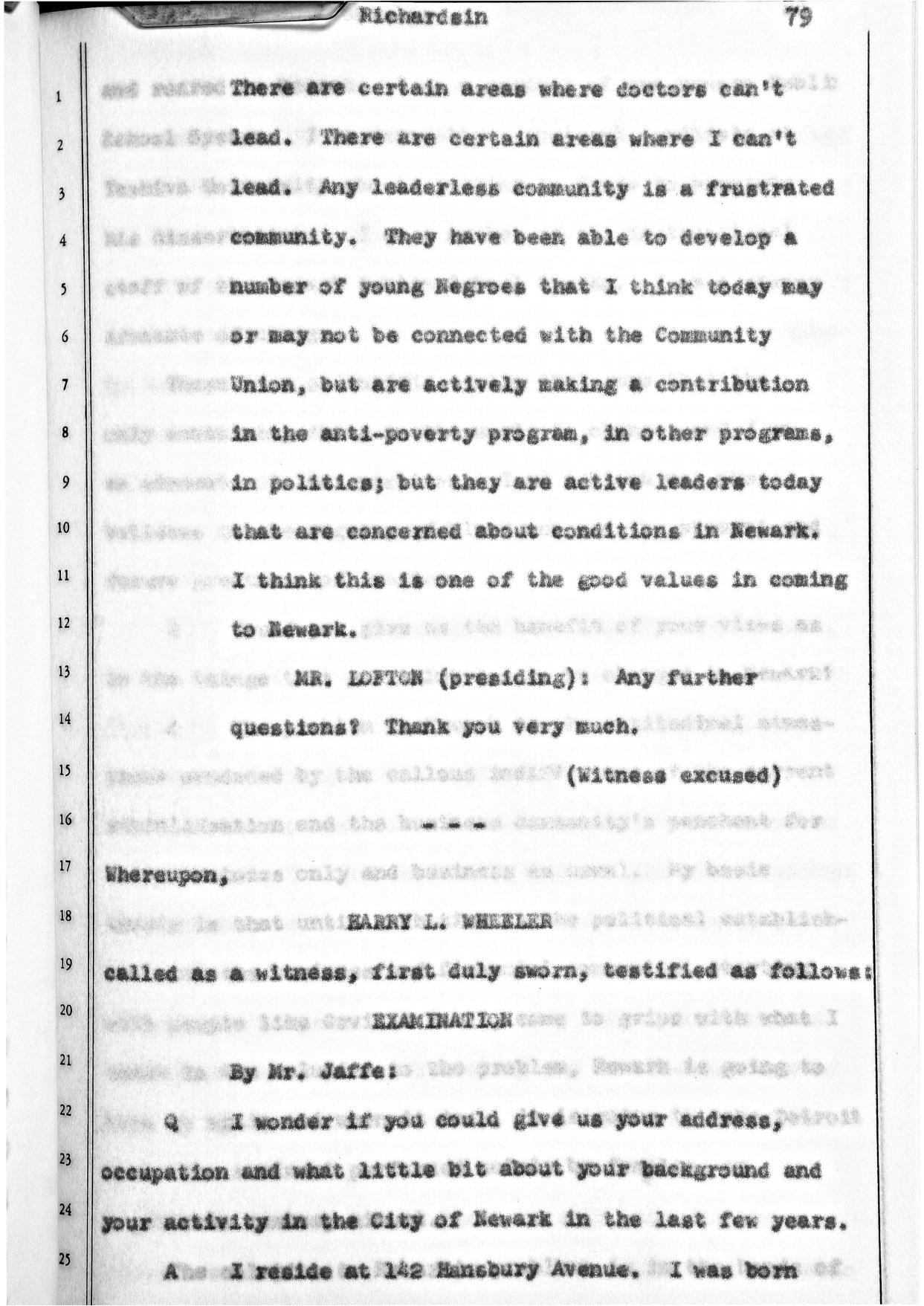

When asked about his background and activity in Newark by a member of the Lilley Commission in 1968, Wheeler stated, “I am a strong advocate of change…I am a Black man who believes in the dignity of Black men and the present and future greatness of America.”

References:

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

Komozi Woodard, A Nation Within A Nation

Komozi Woodard Interview with Honey Ward, 1986.

Leaflet distributed by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund with newspaper coverage of the Medical School Fight. Harry Wheeler is pictured in the bottom right. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Testimony given by Harry Wheeler to the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders on Dec. 8, 1967. –Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository

Edna Thomas recalls a time Newark residents, including Harry Wheeler, stood their ground against police brutality in the city. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Harry Wheeler, Larrie West Stalks, and Mayor Ken Gibson at the NJ State Opera in the 1970s. — Credit: Newark Public Library