Gustav Heningburg

Gus Heningburg was born May 18, 1930 at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where his father taught. He grew up in North Carolina, his family moved to New York City during his senior year of high school, and he graduated from Jamaica High School in 1946. Four years later he received his bachelor’s degree from Hampton Institute and entered the US Army as a commissioned officer. Heningburg served three years in Europe before spending his final three years of service in New Jersey with the Counter Intelligence Corps. Upon retiring from the military in 1957, Heningburg joined the United Negro College Fund and later served for five years as assistant to the president of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

In 1968, Heningburg became the first president of the Greater Newark Urban Coalition, where he served in that capacity and as CEO for 12 years. During his tenure with the Coalition, Heningburg brought together corporate presidents, community organizers, and political figures to “revitalize” the city after the 1967 Newark rebellion. Heningburg sought to use his position of influence in the Coalition to benefit the city’s Black and Puerto Rican populations. “Gus was a tremendous advocate and fighter for those who had been left out,” civil rights activist and community leader Bob Curvin recalled. “My sense is that Gus always knew that he only needed to ask, and hundreds of activists would show up in a minute to march beside him and support his goals.”

Heningburg had a thorough understanding of the workings of government and had an ability to enact policy change, even without public demonstrations. During the Medical School Fight, Heningburg was instrumental in enlisting the support of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and in negotiating with unions and contractors to hire and train Black and Puerto Rican construction workers. The Newark Construction Trades Training Council (NCTTC), which Heningburg helped to organize during the Medical School Negotiations, was responsible for training an estimated 800-900 “minority” workers in the building and construction trades.

When the Black Organization of Students (BOS) “liberated” Conklin Hall at Rutgers-Newark in 1969, Heningburg helped to shape a minority recruitment plan that became known as the Equal Opportunity Fund. Heningburg’s negotiating skills were also highlighted through his roles in resolving the Newark Teacher’s Strike in 1970-1971 and the Stella Wright Tenants Strike in 1973. Heningburg’s role in mediating the Stella Wright Tenants Strike, which was the nation’s longest public housing rent strike, led a federal court judge to remark that “his credibility and his quiet, effective leadership brought order out of chaos, and produced solutions where many thought none existed.” Heningburg also played a pivotal role in battling labor unions to force the employment of Black and Puerto Rican workers in the construction of Terminal B at the Newark Airport.

Of the hundreds of awards and citations that Gus Heningburg received from a wide array of groups during his long tenure as a civic activist and community leader in Newark, Heningburg was most proud of a recognition that he received from the Welfare Rights Organization in 1974. The small plaque read, “…Gus listens to us, fights for us, and we love him.”

References:

“Biography of Gustav Heningburg,” June, 1971.

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Tara Fehr, “Historian uses life experiences to chronicle Newark’s past,” The Star-Ledger, Feb. 11, 2010.

Gustav Heningburg reflects on his role in negotiating with city, state, and federal officials during the Medical School Fight. — Credit: Robert Curvin Collection

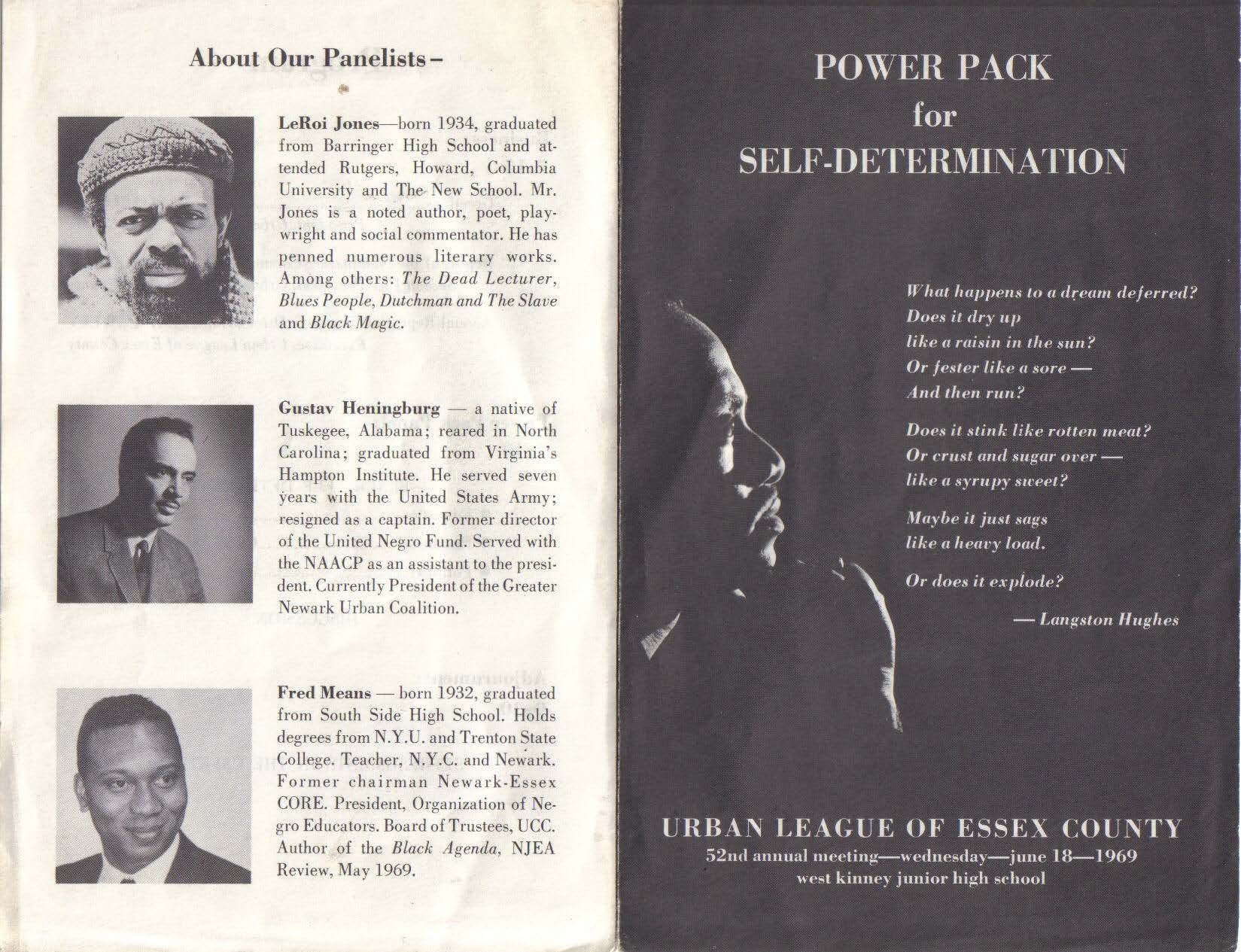

Program for an event held by the Urban League in 1969 titled “Power Pack for Self-Determination,” featuring Gus Heningburg, Amiri Baraka, and Fred Means. — Credit: Fred Means Collection

Former Mayor Sharpe James speaks at the Bethany Baptist Church in Newark during a memorial service for Gustav Heningburg on January 26, 2013. — Credit: Chiara Morrison

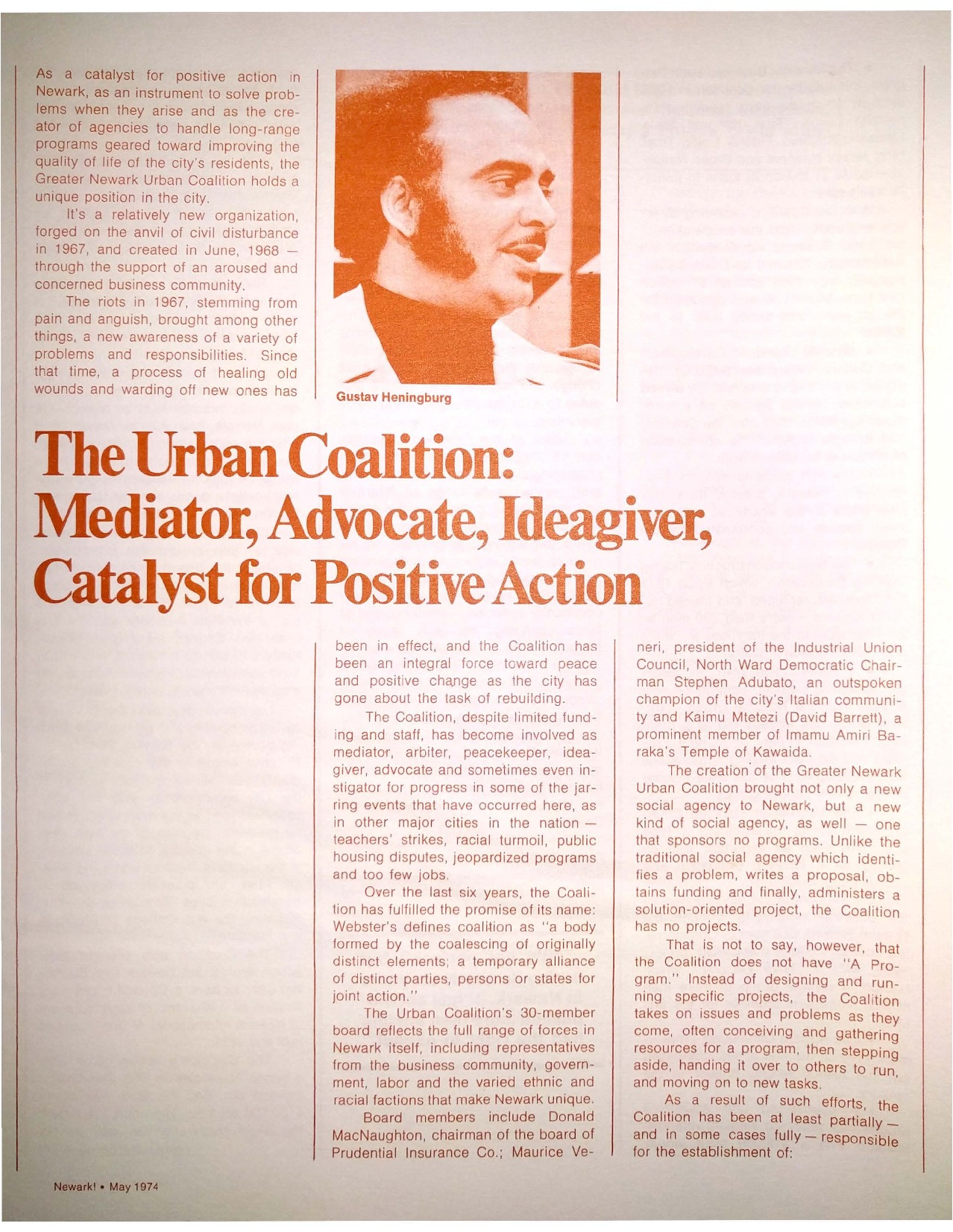

A 1974 article from Newark! magazine, highlighting some of the accomplishments of the Greater Newark Urban Coalition. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Program from a memorial service held for Gustav Heningburg on January 26, 2013 at Bethany Baptist Church in Newark. –Credit: Newark Public Library