The Issue of Welfare

The African American population increase, and the white exodus from Newark in the 1950s and 1960s brought significant changes to the economic composition of Newark. Whites were replaced by a very poor population with heavy demands for public services, particularly welfare. In every category of welfare assistance, Essex County’s expenditures were more than double those of the nearest rival, Hudson County. Newark was the home of the poor in Essex County and municipal expenses increased dramatically. With manufacturing and other job sources leaving the city for the suburbs, following the white former residents of Newark, the increased number of black and brown population became dependent on welfare for longer periods of time, instead of a short stint until the next job came through.

The main county assistance program, Aid for Dependent Children (AFDC) was based on giving help to parents with children who needed basic services to survive (food, shelter, clothing). Thousands of AFDC parents, usually mothers, and hence the tem “welfare mothers,” were dependent on the few dollars paid out at the first of the month for these essential services. A separate program was managed by the city of Newark for poor individuals, with an even smaller payout.

With all welfare programs comes bureaucracy. People are hired to give out the money periodically to those in need. With bureaucracy comes rules, and interpretations of rules. Those in charge were given discretion as to how, when and how much to give, dependent upon how they interpreted the need of the person standing before them. Some of the rules were particularly hard, such as the “no-man-in-the-house” rule. Welfare workers would show up unannounced and inspect the homes of the recipients. If there were evidence that a man was present in the home, the welfare mother would be cut off. The assumption: the man had money to pay because he could get a job.

Welfare workers also took their time in issuing checks, sometimes feeling the person in need wasn’t so bad off as to need prompt attention. And welfare workers developed attitudes against the very clients they were paid to service, reflecting a class divide that was fueled by what they saw, heard and otherwise perceived in the way welfare recipients carried and presented themselves. White and black caseworkers sometimes believed the poor were poor because they just didn’t want to work, or didn’t have the ability to do any better.

It was a system that thrived on conflict. The Newark Community Union Project (NCUP), the multi-racial community group situated in Lower Clinton Hill, and the United Community Corporation (UCC), the War on Poverty group in Newark, developed organizers and welfare recipients who learned the regulations and advocated sometimes successfully for people to get what they deserved from the county and city programs. These people and their efforts were the forerunners of the local chapter of the National Welfare Rights Organization, a national movement for welfare rights and reform that emerged in the late 1960s.

References:

Kathryn Yatrakis, ”Electoral Demands and Political Benefits” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1981)

Clip from an interview with Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) organizer Carol Glassman, in which she describes the ways that stores and social workers in Newark exploited welfare recipients. Many stores, like the Clinton Hill Meat Market, would overcharge customers who bought on credit and trap them in a cycle of debt owed to the store. Glassman also explains how some social workers would withhold welfare checks until debt was paid to these stores, which was against welfare regulations. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Compilation of clips from the short documentary film “With No One to Help Us,” produced by Project Head Start with funding from the U.S. Office of Economic Opportunity. The flim, narrated in part by Marion Kidd, head of the Welfare Committee of the People’s Action Group (UCC Area Board #3), documents the organization of a consumer buyer’s club for welfare recipients in the community. Established as a response to the discriminatory business practices that grocers used against welfare recipients, the Welfare Committee organized the consumer buyer’s club to buy groceries collectively at wholesale prices to help mothers on welfare save money.

Explore The Archives

Clip from an interview with National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO) member Dr. Guida West, in which she discusses what causes women to seek welfare support. Dr. West explains that a number of factors, including illness, unemployment, and family crisis, can lead women to seek temporary assistance from the welfare system. Despite popular stereotypes of lifetime dependency, Dr. West explains that being on welfare “is an in-and-out situation. It is not a perpetual system.” — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

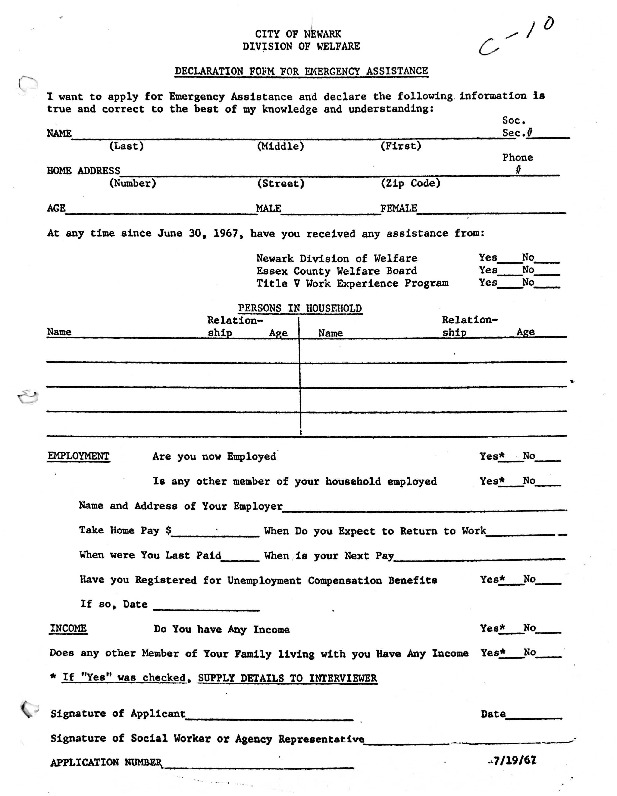

Application form for emergency assistance through the City of Newark’s Division of Welfare. The regulations for welfare recipients could be very strictly enforced, particularly in regards to living arrangements and sources of income, and could result in termination of benefits. — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

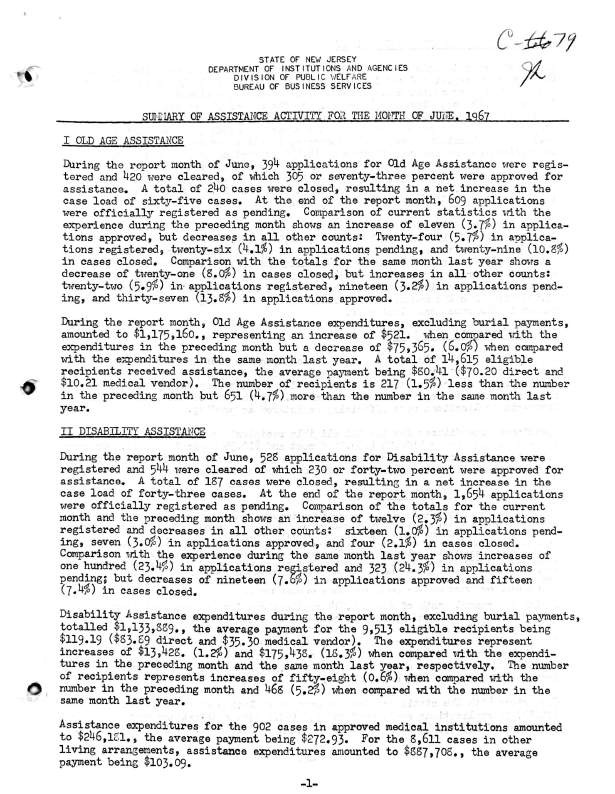

Summary report from New Jersey’s Division of Public Welfare on the state’s assistance activities for the month of June, 1967. The report provides detailed information on the type and scope of welfare assistance provided, along with important statistics on “length of time on assistance” (p. 4) and “amount expended on assistance per inhabitant” (p. 5). — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

Clip from an interview with Cyril Tyson, founding executive director of the United Community Corporation (UCC), in which he explains how the welfare system prevented recipients from escaping poverty. Tyson explains that because of the way the welfare system was regulated, “you don’t have an opportunity to leverage your money in a way in which you can actually get out of poverty.” The Welfare Committee of UCC’s Area Board #3 organized to create programs that would protect the rights of welfare recipients and try to help them out of poverty. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from an interview with Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) organizer Carol Glassman, in which she describes the ways that stores and social workers in Newark exploited welfare recipients. Many stores, like the Clinton Hill Meat Market, would overcharge customers who bought on credit and trap them in a cycle of debt owed to the store. Glassman also explains how some social workers would withhold welfare checks until debt was paid to these stores, which was against welfare regulations. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from an interview with United Community Corporation (UCC) member Mary Smith, in which she describes the misconceptions that people had about African American welfare recipients in Newark. Mrs. Smith explains how people were “blaming us for not working, blaming us for being on welfare,” despite the the efforts of welfare recipients in Newark to get off of welfare and gain meaningful employment. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

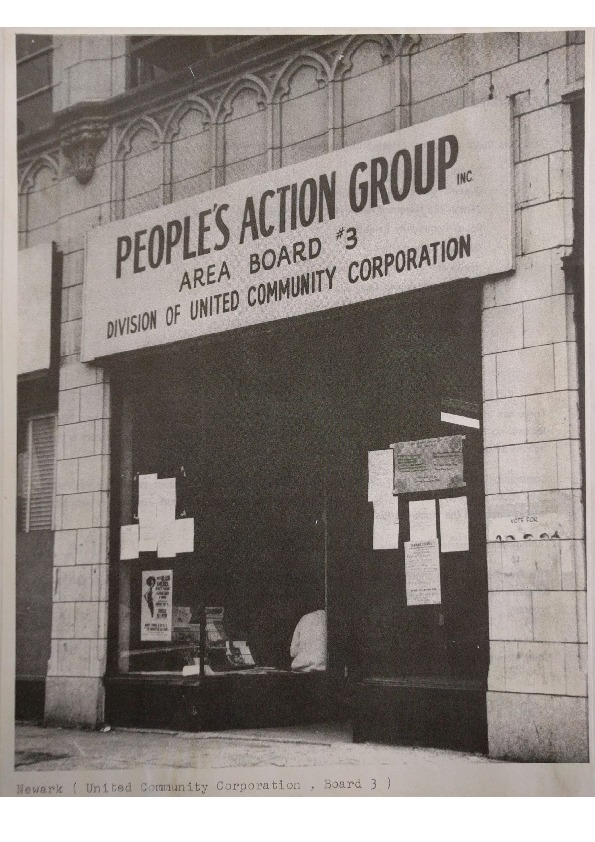

The office of the People’s Action Group at 471 Clinton Avenue in Newark. The People’s Action Group was the name of Area Board #3 of the United Community Corporation (UCC). — Credit: Newark Public Library

Compilation of clips from the short documentary film “With No One to Help Us,” produced by Project Head Start with funding from the U.S. Office of Economic Opportunity. The flim, narrated in part by Marion Kidd, head of the Welfare Committee of the People’s Action Group (UCC Area Board #3), documents the organization of a consumer buyer’s club for welfare recipients in the community. Established as a response to the discriminatory business practices that grocers used against welfare recipients, the Welfare Committee organized the consumer buyer’s club to buy groceries collectively at wholesale prices to help mothers on welfare save money. — Credit: Prelinger Archives

Clip from an interview with National Welfare Rights Organization member Guida West, in which she describes the national significance of struggles for welfare rights. Dr. West explains how poor African American women led these struggles “to change a system that was predominantly used by white women also.” The fight for welfare rights in Newark was part of a national movement to reform and improve welfare programs that discriminated against women of color and limited upward economic mobility. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

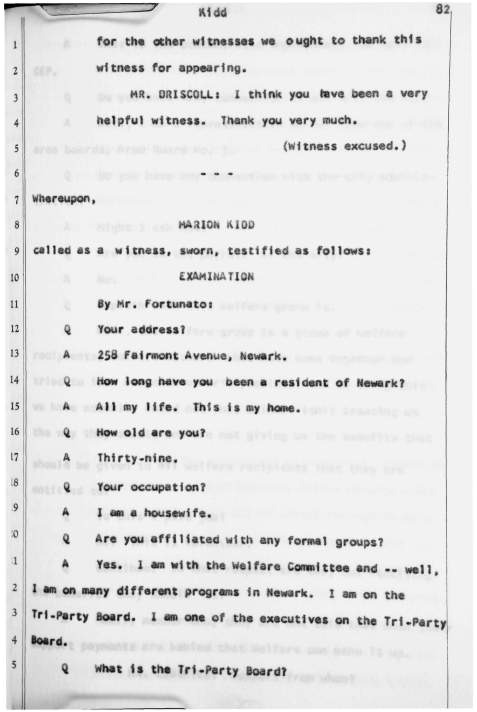

Testimony of Marion Kidd, head of the Welfare Committee of the People’s Action Group (UCC Area Board #3), before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder on October 17, 1967. In her testimony, Ms. Kidd explains the welfare system in Newark and the ways in which her committee organized to protect the rights of welfare recipients in the city. — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository