Robert Curvin

Robert Curvin was born in Newark in 1934 and spent his childhood in Belleville, a predominantly Italian immigrant neighborhood. At 17-years-old, Curvin joined a youth chapter of the NAACP and also enlisted in the Army, where he served five years before being discharged. In 1960, the same year that Curvin graduated from Rutgers University-Newark, organizers from the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) visited the city to recruit volunteers to form a local chapter of the organization. Finding that the NAACP was “too moderate,” Curvin helped to form the Newark-Essex chapter of CORE and served as the chapter’s first chairman.

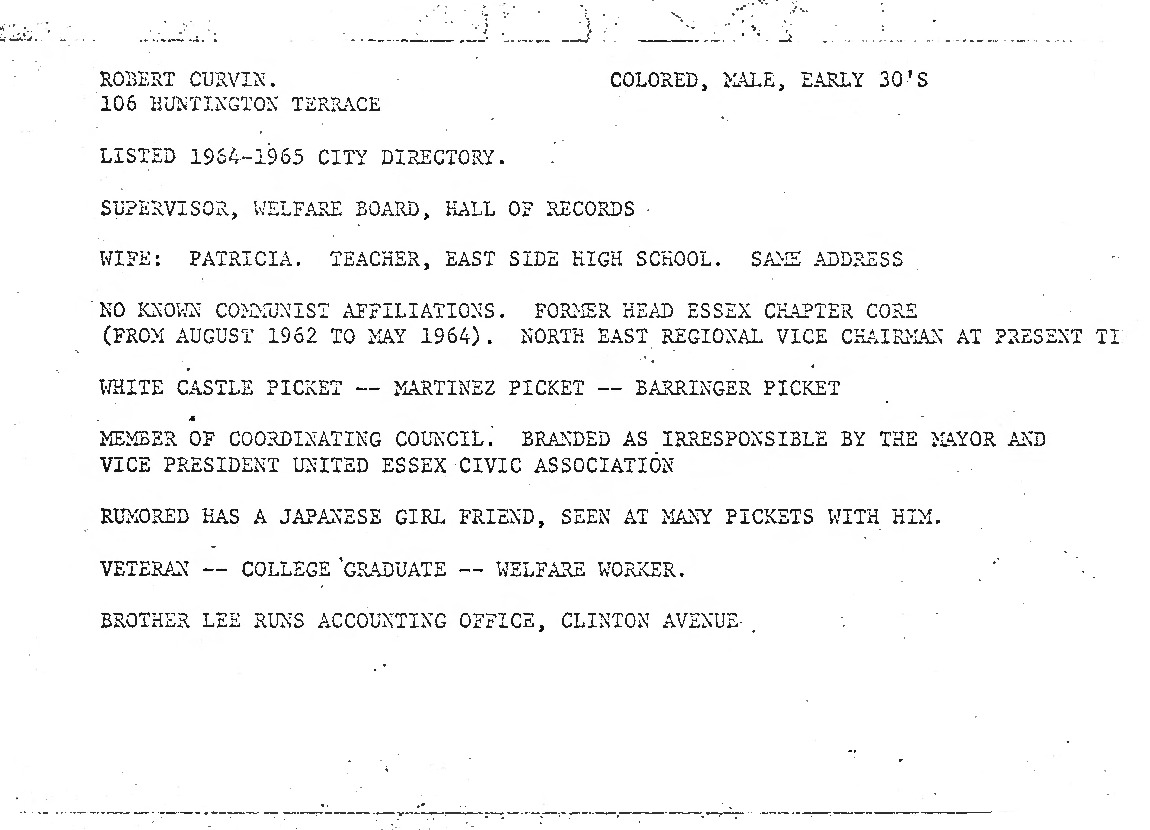

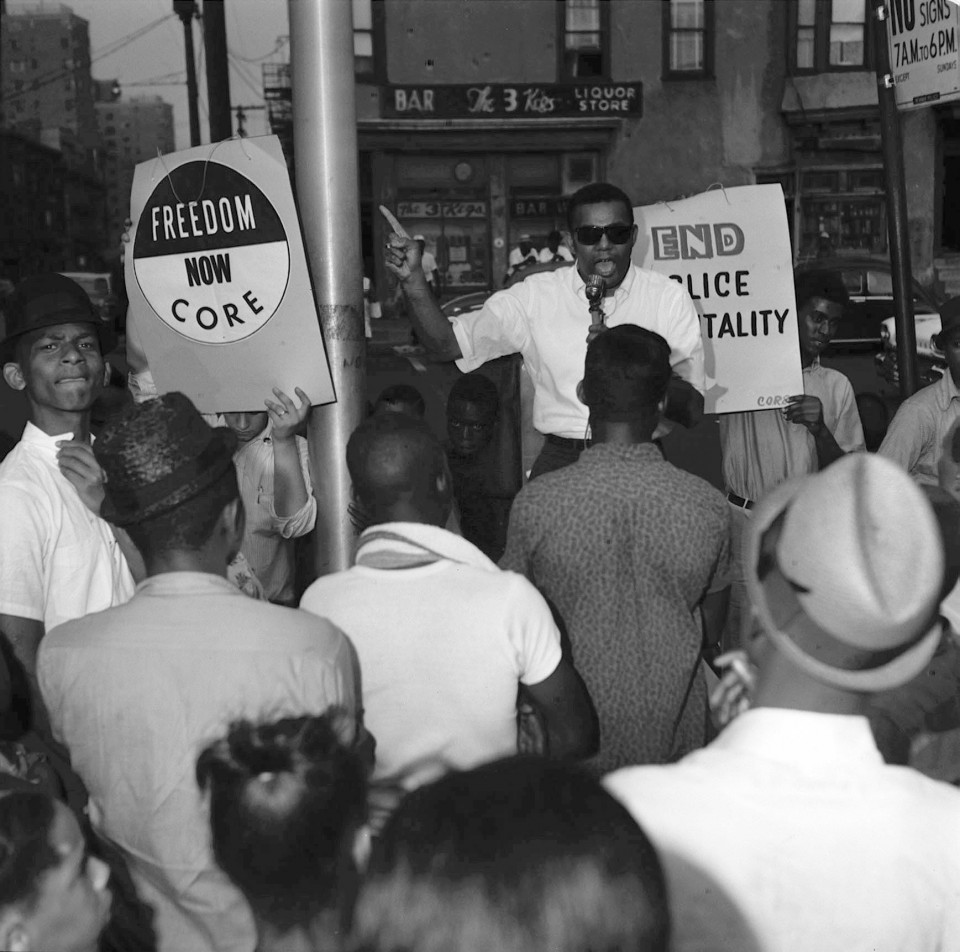

While Curvin was chairman of Newark-Essex CORE, the organization focused on campaigns against discrimination in housing and employment, police brutality, and general discrimination and mistreatment of the city’s Black communities. In 1963, Curvin and CORE joined a coalition of civil rights, religious, and labor groups known as the Newark Coordinating Council to protest discrimination in the building and construction trades at the site of the new Barringer High School. The contentious demonstrations at Barringer marked the arrival of sustained civil rights protests and organizing in the city. During that year, Curvin and CORE also led the charge for a civilian police review board and led protests against employment discrimination at NJ Bell Telephone Co. In 1965, as Northeast Regional Vice Chairman of CORE, Curvin again led the charge against police brutality after Lester Long was fatally shot by Newark Patrolman Henry Martinez.

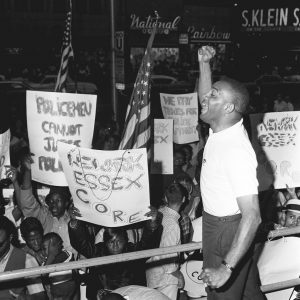

During the rebellion that broke out in July 1967, Curvin found himself front and center outside the Fourth Precinct, where taxi driver John Smith was beaten and held under arrest. Curvin was infamously pictured addressing the crowd through a megaphone outside the precinct. Over the course of those five days, Curvin and other community leaders met several times with city and state officials to advocate for Newark’s Black communities. It was after a Sunday meeting with Curvin and Tom Hayden that Governor Hughes finally agreed to withdraw the National Guard and State Police from the city.

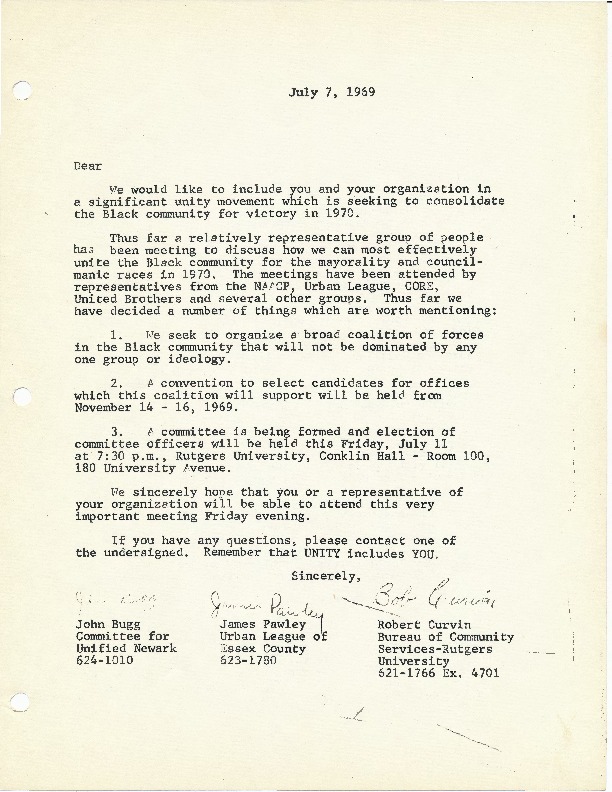

Following the rebellion, Curvin played a central role in the campaign to elect Newark’s first Black mayor, Ken Gibson. Curvin was elected as chairman of the planning committee and executive director of the 1969 Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention. The Convention was assembled to nominate the “Community’s Choice” of candidates in the 1970 mayoral and city council elections. The same year of the convention, Curvin also served as an advisor to the Black Organization of Students (BOS) at Rutgers-Newark in their struggles to increase the recruitment of Black and Puerto Rican students and faculty on campus.

In addition to his activism and organizing during Newark’s Civil Rights era, Curvin went on to earn his doctorate from Princeton University, and serve as a member of the editorial board of The New York Times, director of the Ford Foundation’s Urban Poverty Program, and dean at the New School. Writing of Curvin in his 1992 memoir, historian and activist August Meier stated, “I regard him as gifted as any of the movement’s well-known national leaders.”

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Sam Roberts, “Robert Curvin, Scholar Who Fought Bias and Poverty in Newark, Dies at 81,” Sept. 30, 2015, www.nytimes.com

Robert Curvin speaks at a 2007 panel on the significance and legacies of the 1967 Newark rebellion. — Credit: Sandra King

Newark Police profile on Robert Curvin from 1965. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Robert Curvin speaks at a CORE rally at the corner of Spruce and Belmont following the fatal shooting of Lester Long by Newark Police in 1965 — Credit: Wally Akerberg/The Star-Ledger

Invitation from John Bugg, James Pawley, and Robert Curvin to participate in the 1969 Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection