Nathan Wright

Nathan Wright was born August 5, 1923 in Shreveport, LA and raised in Cincinnati, OH. His mother was a teacher, and his father, an insurance salesman, was head of the Cincinnati branch of the NAACP. In his twenties, after having served in the Army during World War II, Wright became active in struggles for civil rights in his hometown and beyond. In 1946, while a student at the University of Cincinnati, Wright became the focal point of protests after he was randomly stopped and searched by police officers. The next year, he took part in the Journey of Reconciliation, an interstate bus ride through the South, led by the Congress of Racial Equality, to test Supreme Court’s 1946 decision in Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia outlawing segregation in interstate travel.

After graduating from the University of Cincinnati, Wright earned a doctoral degree from Episcopal Theology School in Cambridge, MA and was ordained a minister in the Episcopal Church in 1950. While a minister in Boston, Wright became friends with Louis Walcott, a parishioner who would later be known as Louis Farrakhan, leader of the Nation of Islam. During his time in Boston, Wright also served as the New England field representative for CORE and served on the Governor’s Advisory Committee on Civil Rights.

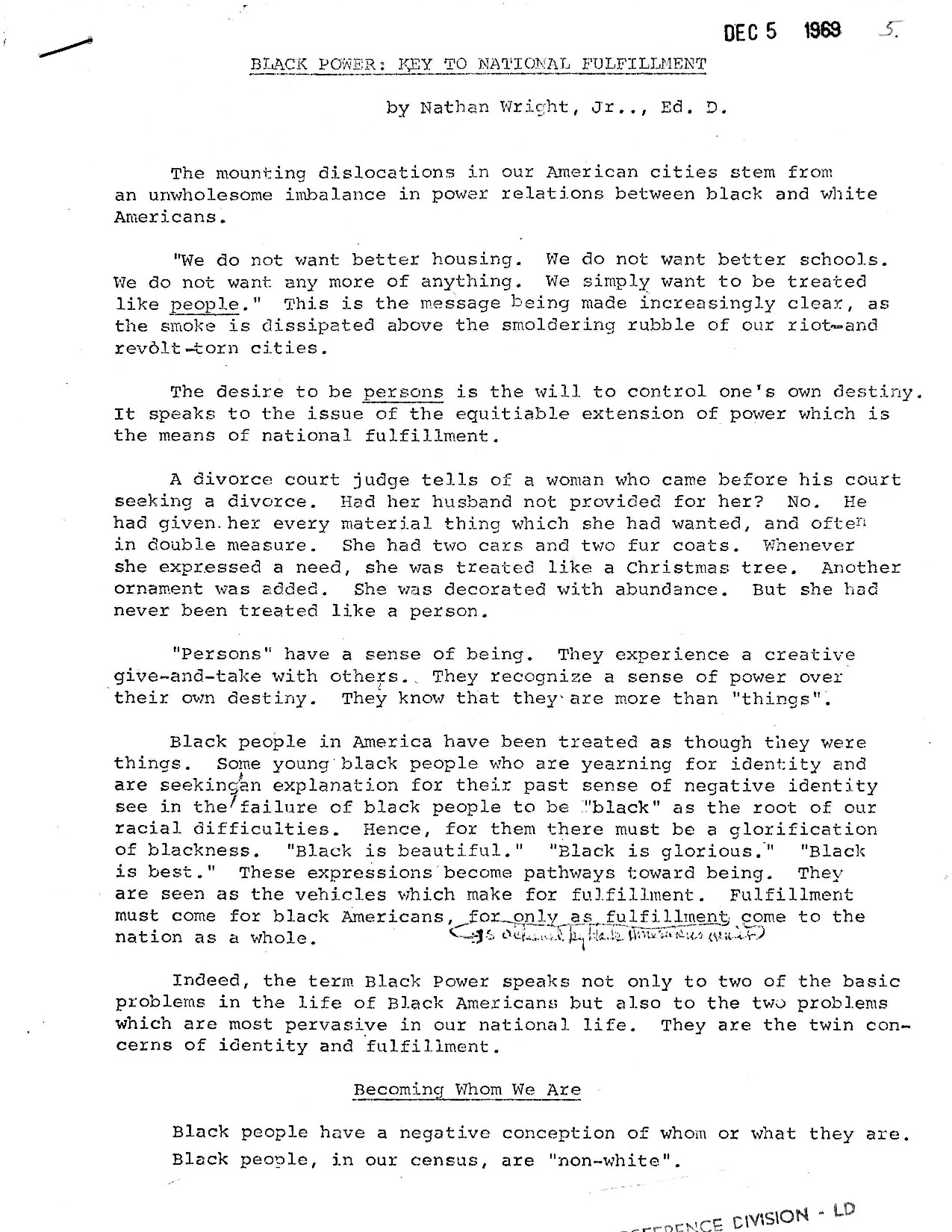

In 1964, Wright became the Executive Director of the Episcopal Diocese of Newark’s Department of Urban Work. When Wright arrived in Newark, the Civil Rights Movement in the city and the nation was reaching a fever pitch as urban rebellions swept the northeast and campaigns for political power swelled in the South. Calls for “Black Power” raised by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1966 marked a new direction in the Civil Rights Movement and set the stage for Wright’s advocacy of Black Power in Newark. Wright is perhaps best remembered for his role in heading the National Conference on Black Power, which was held in Newark just days after the 1967 rebellion.

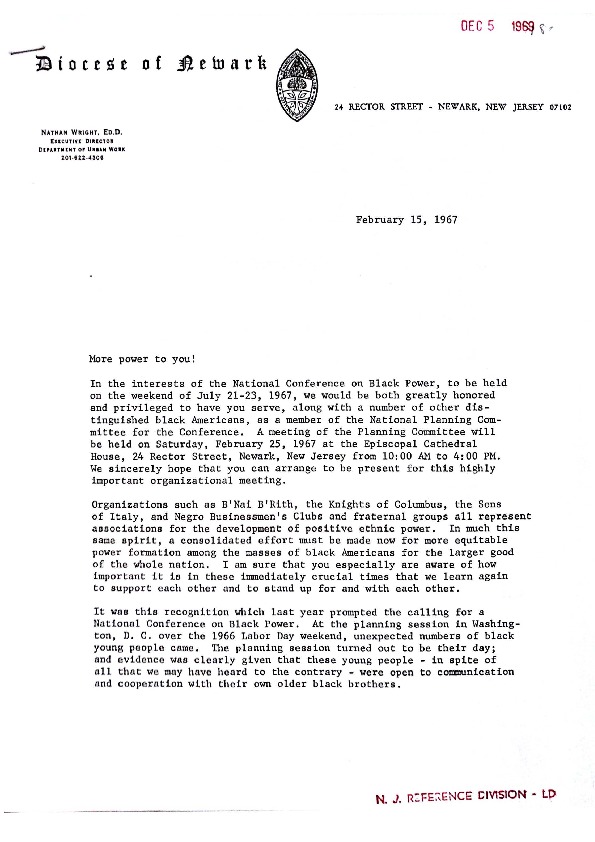

As chairman of the conference committee, Wright sought to organize a national gathering that would bring together national advocates of Black Power to explore the possibilities of Black Power for unifying and empowering Black Americans. The conference brought together over 1,000 participants, including H. Rap Brown, James Farmer, Jesse Jackson, Floyd McKissick, Amiri Baraka, and others representing hundreds of organizations and cities. Speaking to the Conference, Wright said, “After the so-called riots people must be given hope. Others outside the black community must not set an agenda for black redemption. The black community as a whole– which shares a common oppression– must set its own agenda as a whole.”

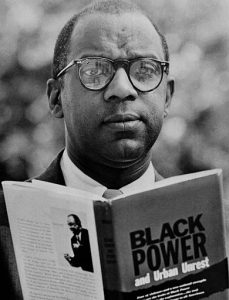

Wright, an avid scholar and author, wrote two books on the Black Power movement: Black Power and Urban Unrest (1967) and Ready to Riot (1968). In 1969, Wright became the founding chairman of the Department of African and Afro-American Studies at SUNY Albany. He remained in academia for many years, while also serving on presidential task forces in the Nixon and Reagan administrations.

References:

Martin Schiesl, “Wright, Nathan Jr. (1923-2005), www.blackpast.org

“Black-Power Leader Nathan Wright Jr. Dies,” Washington Post, March 6, 2005.

Nathan Wright reflects upon the 1967 National Conference on Black Power, held in Newark just days after the 1967 rebellion. Wright was chairman of the conference committee. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Invitation from Dr. Nathan Wright to serve as a member of the National Planning Committee for the National Conference on Black Power, held in Newark from July 20-23, 1967. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Speech presented by Nathan Wright at the July, 1967 National Conference on Black Power in Newark, titled “Black Power: Key to National Fulfillment.” — Credit: Newark Public Library