Mary Smith

Mary Smith was born in the South before moving to Newark as a child. Growing up, Smith’s mother worked as a domestic laborer and her family lived in the rear apartment of a Jewish deli in the city. As an adult, she later moved into the Scudder Homes high-rise public housing project with her five children.

Smith’s entree into activism and organizing came when she started talking to other tenants of the Scudder Homes about the conditions in the buildings. Although the buildings were newly built, there was no hot water, the elevators did not work, and there were no screens on the windows. “I just got so angry,” Smith later recalled, “and here I was a person that had never been involved in any kind of community action or community involvement.” Smith then began talking to other tenants to demand something be done about the housing conditions and became president of the Scudder Homes Tenants Association.

As president of the Tenants Association, Smith’s activism and leadership reached far beyond the grounds of the Scudder Homes project. In addition to organizing tenants to improve the shoddy conditions of the apartment buildings and to demand better police protection, Smith also became involved in struggles for police reform. During a 1965 struggle for a civilian police review board, Smith took part in the Newark Police Department’s “citizen observer” program, during which she recalled witnessing acts of police brutality. The program, offered by the Department as a compromise to community demands for police oversight, was a massive failure.

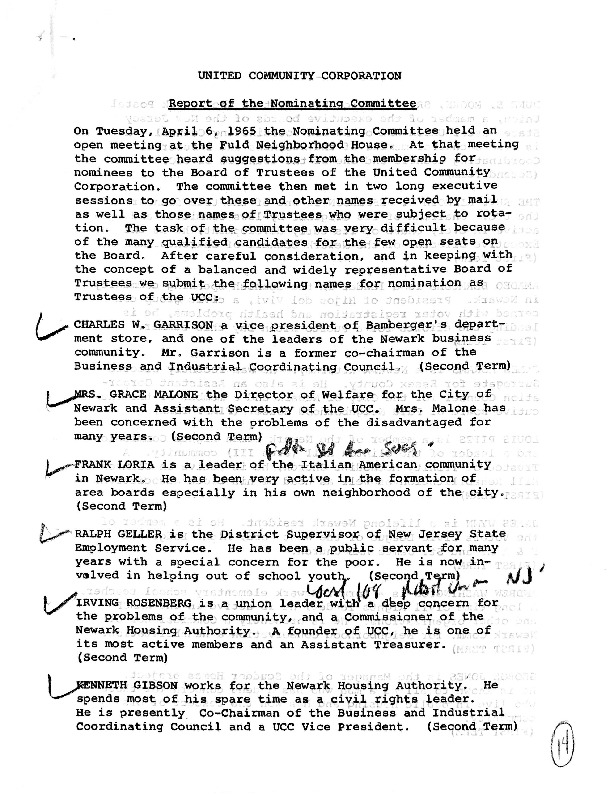

When the War on Poverty came to Newark in 1965 in the form of the United Community Corporation (UCC), Smith became active as a member of the nominating committee and worked for the UCC’s Newark Senior Citizens Commission. However, due to insufficient funding, many of the programs that Smith hoped to build never came to fruition.

In 1968, after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, Smith was asked to take part in a panel in the predominantly white suburbs about what life was like for Newark’s Black communities. In speaking with women after the panel, Smith and others organized “Operation Housewives,” which quickly grew to 20 suburban chapters. The premise of the organization, according to Smith, was for affluent white women to advocate for the needs of Newark’s Black communities and get their husbands and other men in their communities who controlled large corporations in the city to open up job opportunities and training programs to Black workers.

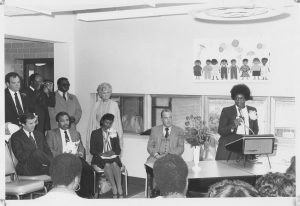

One of the most successful outgrowths of Operation Housewives was the establishment of Babyland Nursery. For years, Smith had tried unsuccessfully to work with the Newark Housing Authority to establish a daycare center within the Scudder Homes. With a loan from AT&T president Robert Lilley (who also chaired the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder) Smith established Babyland Nursery, which opened its first of several childcare centers in 1968. Developing a partnership with the New Community Corporation, which Smith was also a member of, Babyland eventually grew to become the largest infant daycare center in the state.

References:

Interview with Mary Smith, Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Irene Cooper-Basch, “The Evolution of Victoria Foundation From 1924 to 2003” (PhD diss., Rutgers-Newark & NJIT, 2014).

Carl Koechlin, “Integrating Compassion and Pragmatism in a Successful Community Development Strategy” (M.A. thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 1989).

Mary Smith describes how her involvement in tenant organizing translated into community and political organizing. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Report of the UCC Nominating Committee regarding nominees for UCC Trustees. Mary Smith was a member of the committee. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Mary Smith reflects on her struggles during the Civil Rights Movement and talks about her hopes for Newark’s future. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries