Louise Epperson

Born in Waynesboro, Georgia in 1908, Louise Epperson came north to Newark in 1932. Coming of age during the Great Depression, Epperson helped her neighbors in Newark to find jobs in President Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration. After holding a few different jobs as a domestic worker and medical receptionist, Epperson eventually took a job at Willowbrook State School in Staten Island, where she became the facility’s first African American occupational therapist.

Epperson became involved in city politics during Irvine Turner’s campaign to become Newark’s first African American city councilman in 1954. She later reflected “Irvine didn’t have too much power– he did whatever he could do. He never let us down, we were so proud of him.” Epperson also canvassed for Harry Hazelwood, who became the city’s first African American municipal court judge in 1958.

Although active in these campaigns in the 1950s, Epperson truly made her mark in the city during the mid-1960s when the City of Newark and State of New Jersey conspired to relocate the College of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey in Newark’s predominantly Black Central Ward. Upon hearing of the plans on the first day of 1967, Epperson recalled, “Immediately, I went to see the mayor…he said, ‘well, we are coming in whether you like it or not– we’ll just do an eminent domain.’ And I said, ‘then you’ll just have to run me over with the bulldozer, because I’m not moving.”

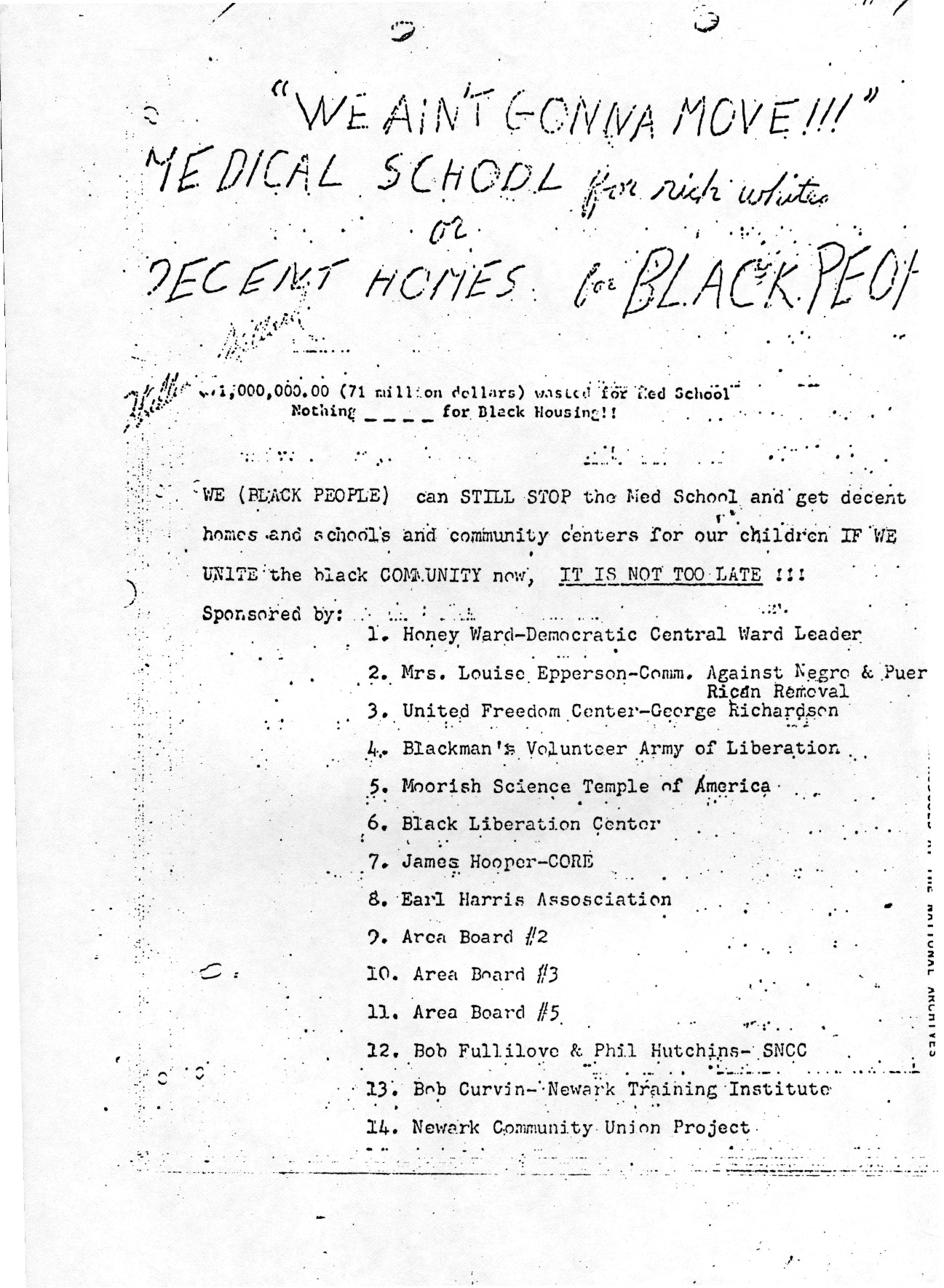

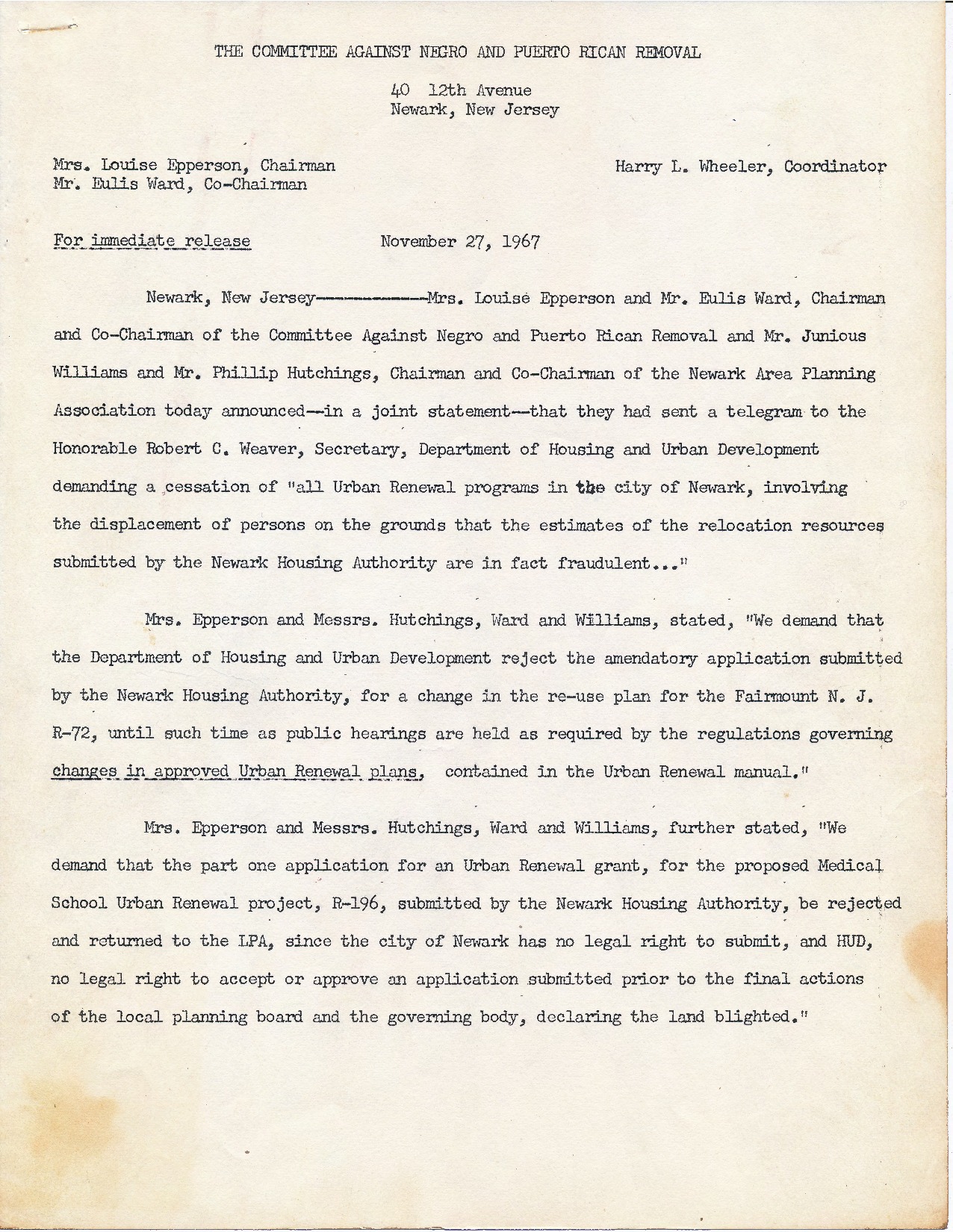

Epperson immediately began holding meetings in her home and public spaces with her neighbors to organize resistance to the plans for a medical school that would displace 20,000 residents of the Central Ward without their input or consent. Realizing the need to reach people where they were, Epperson brought her organizing into bars and clubs in the city, at times even getting into the go-go dancing cages to exhort patrons to action. Epperson’s grassroots organizing resulted in the formation of the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal, with the assistance of Harry Wheeler, Honey Ward, and Russell Bingham.

Epperson and the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal, along with the Newark Area Planning Association (NAPA) were instrumental in protesting the original plans for the medical school and negotiating with city and state officials to implement an alternate plan on fewer acres. The 1967 Rebellion helped to galvanize their struggle and compelled city and state officials to seek out a compromise and negotiation. Epperson remembered, with a big smile on her face, “I tried for weeks, months to get in touch with Dr. Cadmus, who was president of CMDNJ [the Medical School]…but, after the riots broke out, then, everybody wanted to talk to me.”

After the Medical School Agreements were negotiated, where she played an important role with Harry Wheeler and Junius Williams, she became the only female member of the United Brothers, the beginning of a Black united front spearheaded by Amiri Baraka. Louise Epperson was also active in the Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention, held in 1969 to nominate the “Community Choice” for city council and mayor in the 1970 election. The efforts of the Convention resulted in the election of Newark’s first Black mayor, Ken Gibson. She was also the first Black person appointed to the Newark Board of Health and used her position to advocate for patients and the healthcare needs of her community. After initially turning down offers, she took a job at the Medical School, where she created an important patient relations program.

Community activist and scholar Robert Curvin later wrote of Louise Epperson, “Epperson was not slick or learned; she was blunt and passionate and carried herself in a way that made people listen to her and respect her. Community leaders admired her.”

Reflecting years later on her struggles during Newark’s civil rights era, Epperson recalled “we had nobody in City Hall…We only had good mother-wits, and we just used that mother wit. It made me think about Fannie Lou Hamer, and all the other soldiers that fought during the struggle for black folks to try to make it. We had to struggle, we had to persevere, no matter what happened.”

References:

Katie Singer, “Over My Dead Body!” Newest Americans, Issue 02, Winter 2016.

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Louise Epperson reflects upon her experiences during the Medical School Fight in Newark. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

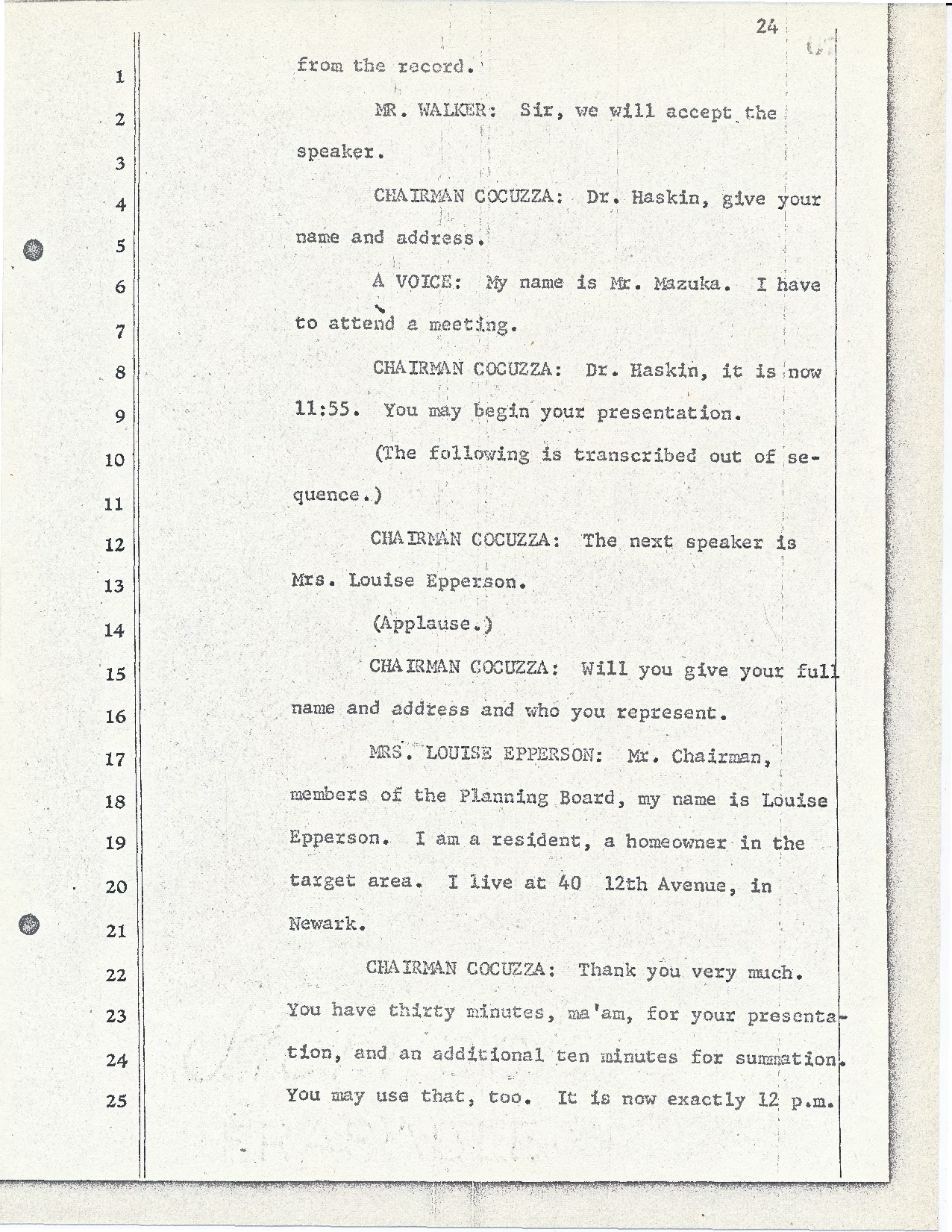

Transcript of Louise Epperson’s statement to the Central Planning Board on June 13, 1967 during the Medical School “blight hearings.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

Flyer distributed to encourage community members to protest the seizure of land for the construction of a medical school in the Central Ward. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Letter from the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal to Robert C. Weaver demanding that all urban renewal projects in Newark be stopped. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection