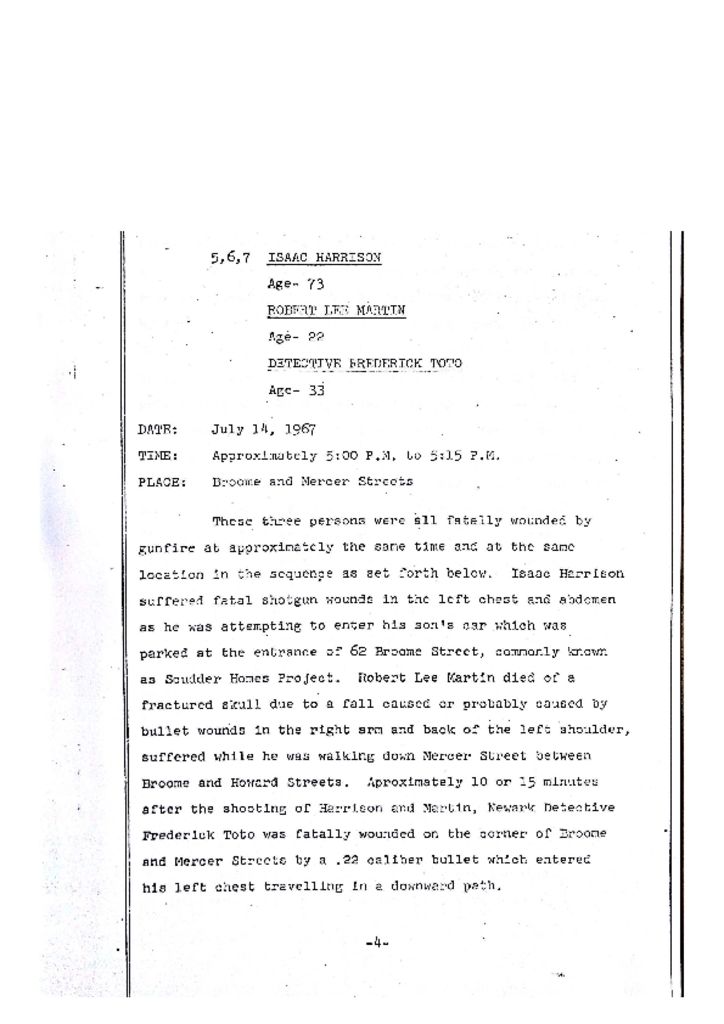

Isaac Harrison

Isaac Harrison left Jamaica in the 1910s for a new home in Burlington, New Jersey. There, Harrison and his wife, Evelyn, started a family before eventually moving to Newark in 1943. The Harrisons raised nine children in Newark while Isaac worked in iron foundries around the city. In February of 1967, Evelyn passed away and Mr. Harris went to live with his eldest son Ike’s family in their apartment on the 10th floor of the Scudder Homes project.

Around 5:00 P.M. Friday July 14th, Mr. Harrison and three of his sons, Virgil, Bussy, and Horace, were standing in a crowd on Broome Street outside of the Scudder Homes project when three police cars coming from Springfield Avenue turned onto the block. Springfield Avenue had been the setting for much of the “rioting” and “looting” over the past two nights, but Broome Street had been relatively calm that day.

According to witnesses, as soon as the cars turned onto the block, police officers got out and opened fire on the crowd. ‘It was a matter of seconds,’ Bussy Harrison said. ‘They pulled up, got out of their cars and started firing. There was no warning, nothing.’ Virgil Harris echoed his brother’s account: ‘They just got out of the cars and started shooting. There weren’t any looters running around us…At first I thought they were firing blanks ‘cause they were shooting directly into the crowd.’

“When we saw they were really shooting at us, we went for the entrance there,” Virgil Harris continued. “My father got hit then. I thought he had just fell because everyone was pushing, so I picked him up and I was helping him up the steps when I got shot in the arm. When I got by the door, I got shot in the knee and I went down. Somebody pulled me in the doorway. My father was already in there, he was bleeding badly and moaning. They were still shooting at the building outside.”

The presentment of the Essex County Grand Jury, which heard testimony on the killings during the rebellion, asserted that “Newark police responded to a radio call, checked the location, and upon return to their car they were met by sniper fire apparently coming from the Project. The police retaliated by firing upon the Project…”

Although “sniper fire” was widely reported by police and National Guardsmen, very little evidence was found to support the 258 reports of “sniper incidents” claimed by city and state police. Furthermore, reporting “sniper fire” was used as a justification for the indiscriminate shooting of innocent civilians, as in the case of Isaac Harrison.

Given the lack of radio communication between law enforcement agencies during the rebellion, it is likely that the reported “sniper activity” was actually the multiple shots fired at 22-year-old Robert Lee Martin by police around the corner on Mercer Street just moments before.

According to Mr. Harrison’s stepson Horace Morris, who was with him outside the Scudder Homes, ‘We were under fire, I would say, for approximately ten minutes by the Newark police. They said they were looking for a sniper on the roof or the upper floors of the building but they were still firing at ground-level range.’

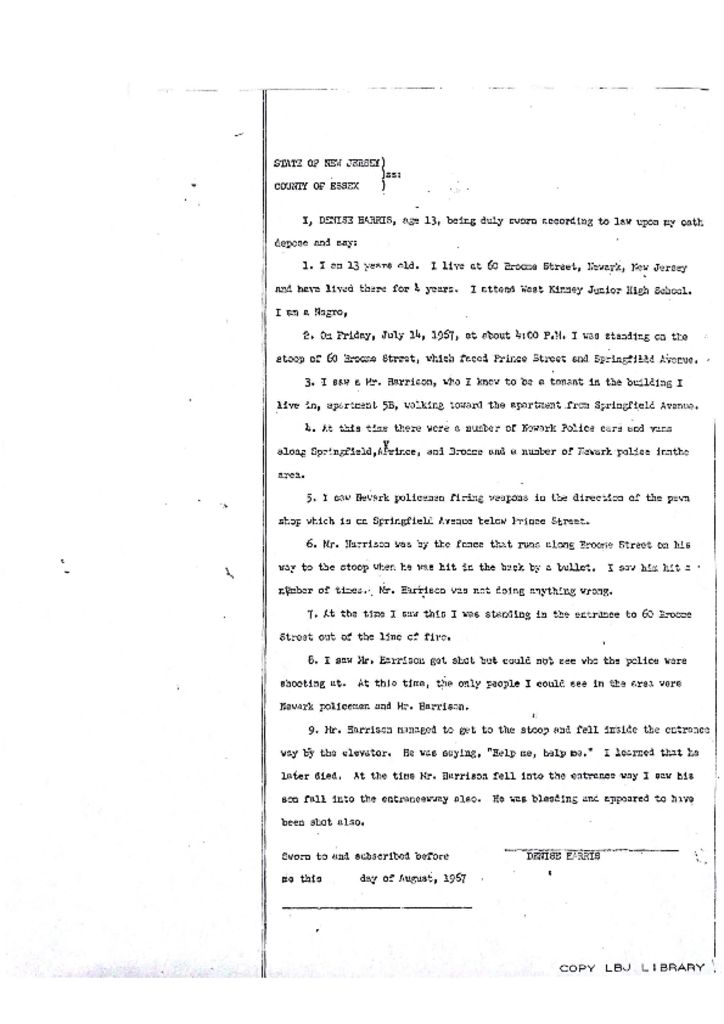

Isaac Harrison was dead at the age of 73 after having been shot five times in front of his home by policemen firing indiscriminately into a crowd of people. According to witness Denise Harris, “Mr. Harrison was by the fence that runs along Broome Street on his way to the stoop when he was hit in the back by a bullet. I saw him hit a number of times. Mr. Harrison was not doing anything wrong.”

The Essex County Grand Jury found “no cause for indictment” of the officers

References:

Ronald Porambo, No Cause for Indictment: An Autopsy of Newark

Witness Testimony of Denise Harris before the Essex County Grand Jury

Deposition of Denise Harris, in which she describes Isaac Harrison being shot in the back by Newark policemen on Friday, July 14th. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Grand Jury report describing the fatal shooting of Isaac Harrison on July 14, 1967. The Grand Jury found “no cause for indictment.” — Credit: Newark Public Library