Edna Thomas

Edna R. Thomas was born in Newark on June 17, 1941 and went to Morton Street and Robert Treat School before attending Arts High School. After she gave birth to her son, Thomas moved to an apartment on High Street (now MLK Blvd), where she lived next door to Central Ward Councilman Irvine I. Turner. While living next door, Thomas began answering the phone for Turner when she was unemployed. This proved to be an invaluable political experience for Thomas, who later said, “I began to meet a lot of politicians that would come in and out of his office and began to learn from them. That was very helpful to me.”

In 1965, the War on Poverty came to Newark and took shape as the United Community Corporation, Newark’s Community Action Agency. Before joining the UCC, Thomas worked at a toy factory– a job that paid $1.15 per hour, left her unemployed for half the year, and required her to collect welfare for subsistence. In addition to working and caring for her children, Thomas also served as the Vice President of the Scudder Homes Tenants Association. However, when she heard about the UCC, Thomas said, “I stood there with tears in my eyes and said I wasn’t coming back. I was going to do something better and that’s when I started volunteering for the anti-poverty program when he called for volunteers.”

In her time with the UCC, Thomas served on the Board of Trustees, along with a number of other roles, including Vice President of Area Board #2, Operation We Care, located at 415 Springfield Avenue. As a member of UCC, Thomas was actively involved in organizing around issues in public housing and education. In housing, she fought not only for badly needed low-income housing, but also to ensure that public housing projects were kept safe and sanitary for residents.

Thomas also fought for improved educational opportunities for the city’s children. Recalling efforts to have a curriculum specialist employed by the public school system, Thomas recalled, “I remember when we were sitting down in my living room– myself, Tim Still, Mary Smith, and Esta Williams. And we just sat there talking about what we don’t have. And before I knew it, the next day, we were on our way down to Addonizio’s office.” When asked what they were doing there, Thomas responded “We come because it’s about time!”

References:

Edna R. Thomas Interview, retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.7282/T3G73GRN

Interview with Edna Thomas, Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Thomas describes how “urban renewal” led her to become active in struggles for justice and equality in housing and education for Newark’s Black communities. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

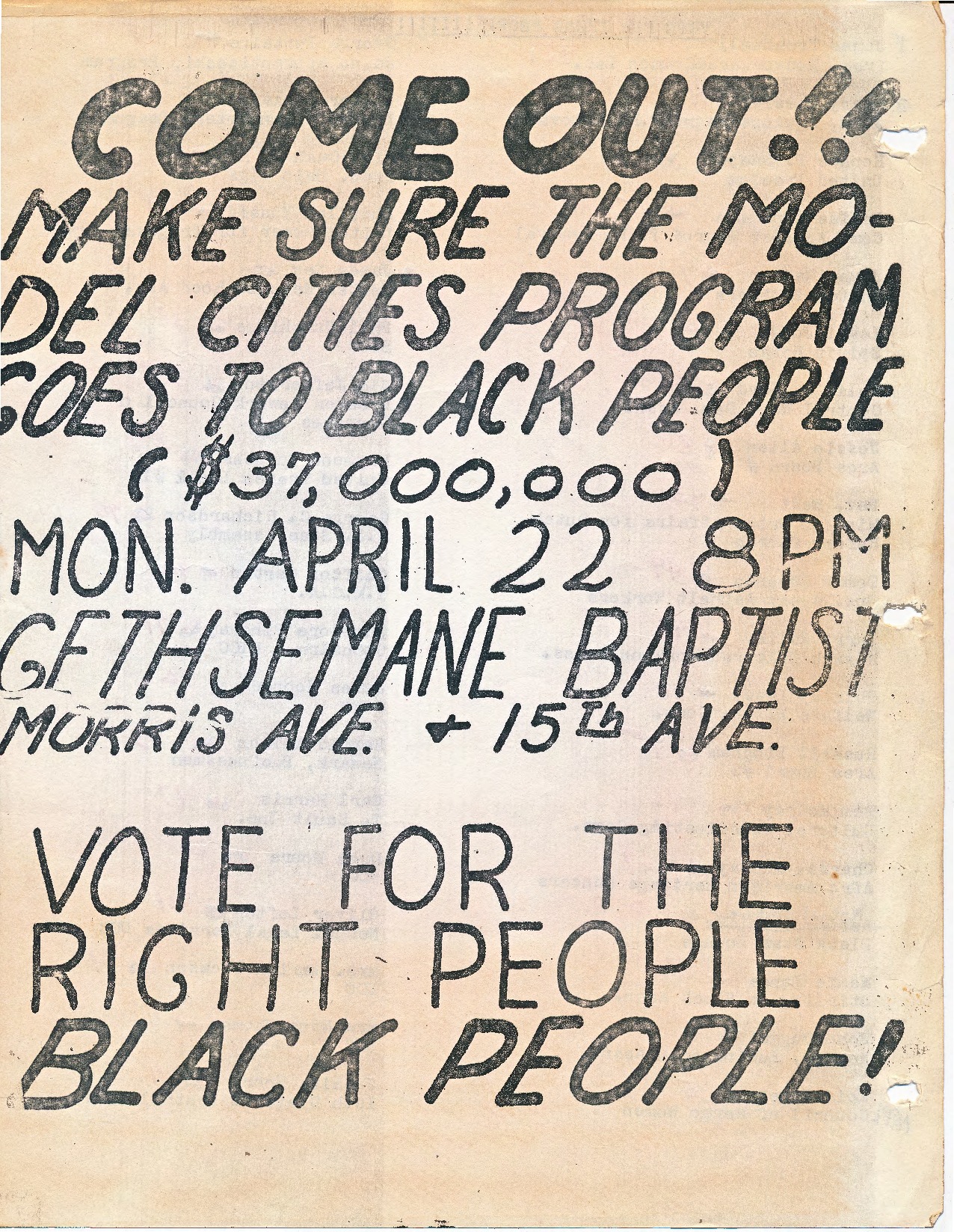

Flyer for the Model Cities Neighborhood Council election on April 22, 1968. Edna Thomas was a community candidate in the election. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Edna Thomas describes the particular abuses that Black women suffered from Newark policemen. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries