Derek Winans

Derek Winans was born September 4, 1938 and came from a line of prominent Newarkers. His father, James Dusenberry Winans, was a well-known progressive political activist and owned the C.G. Winans Company, a salt, paper, and twine manufacturer. Derek’s family tree could be traced back to the founding of Newark, and his great-grandfather fought in the Civil War.

As a journalist by trade, Winans wrote and edited for the Herald Advance, Plainfield-Courier, and the Wall Street Journal. However, Winans found the profession to be unfulfilling and eventually dedicated himself to full-time civil rights activism. Despite his full-time dedication to advocacy work, Winans used his writing and editing expertise to develop and assist progressive media outlets. Winans served as a writer and editor for the New Jersey Advance Newspaper, a progressive black publication that provided arguably the most thorough accounts of struggles for Black equality in Newark during its short run from 1965-66.

“Derek was a lean, pipe-smoking Harvard graduate,” Bob Curvin later wrote. “He usually seemed to work on the periphery of various Newark groups, except for the Essex County Chapter of Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), of which he became the president. During his tumultuous leadership of ADA, he turned the organization upside down, partly because it did not move far and fast enough on civil rights issues. He discovered more comfort as advisor and strategist for other more engaged grassroots organizations. In 1963, after the burst of demonstrations over discrimination in the construction trades, Derek helped to shape the idea of a Business and Industrial Coordinating Council (BICC).”

When Tom Hayden and the Students for a Democratic Society (SD) students came to Newark, Winans joined in their organizing efforts to combat discrimination in housing and employment. He also became involved in the United Community Corporation (UCC), Newark’s War on Poverty agency, and served as director of the agency for a period. Winans also went on to work on education and housing issues as part of City Councilman Donald Tucker’s staff.

In the 1970s, Derek was also the founder of the Newark Community Project for People with AIDS. Later in that decade, he began volunteering as a planner and grant writer for the International Youth Organization (IYO), a local community organization. Its leader, Caroline Wallace, came to rely on Derek not only for his grant writing but also for his skill as a counselor for the young people the organization served. Derek always faced periods of drought by showing up every day, without compensation, and helping to get IYO on its feet again.

Derek continued to work on issues such as welfare and tenants rights throughout the 1970s and 1980s. “Until his last days,” the New Jersey Historical Society later wrote, “he worked as an activist for the people of Newark.”

References:

Robert Curvin, from Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

New Jersey Historical Society, “Guide to the Derek Winans Papers,” 2006.

Derek Winans describes how he became involved with the Newark Community Union Project. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

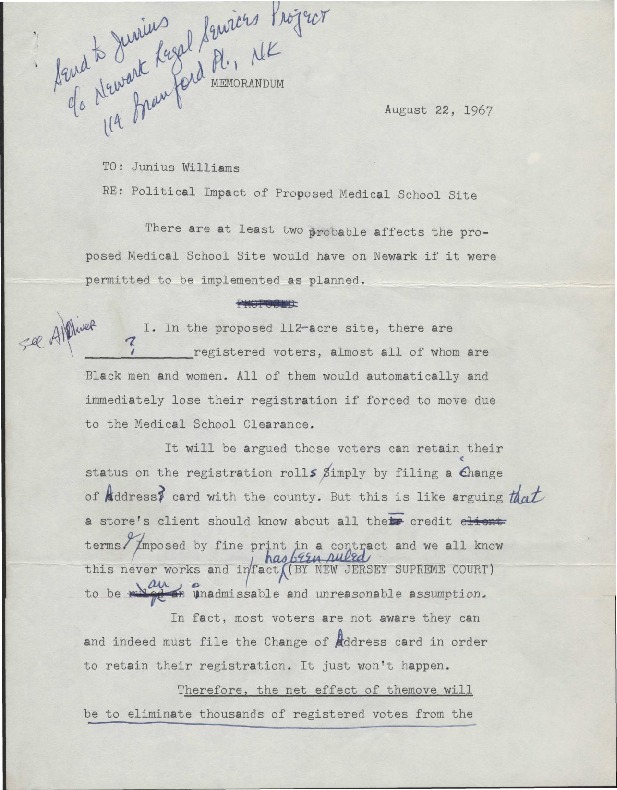

Memo from Derek Winans to Junius Williams on August 22, 1967 regarding the political impacts of the proposed Medical School site in the Central Ward. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Derek Winans explains how the Civil Rights Movement influenced the direction of politics in Newark in the 1960s. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection