The United Brothers and Committee for Unified Newark

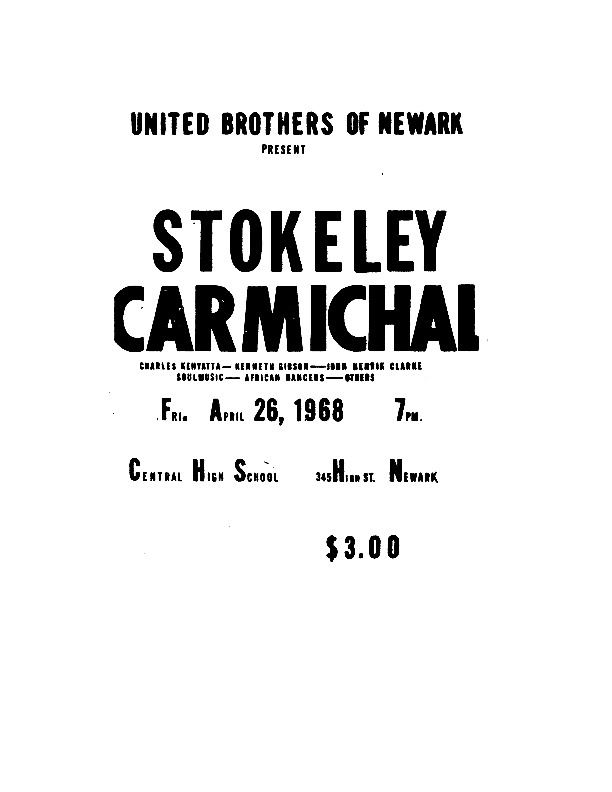

In November of 1967, two friends of Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), John Bugg and Harold Wilson, sent out a letter inviting a small group of African American leaders to meet at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Newark on December 8th. Twelve men and one woman were asked to be a part of the development of a “Black United Front” to take power in the election of 1970.

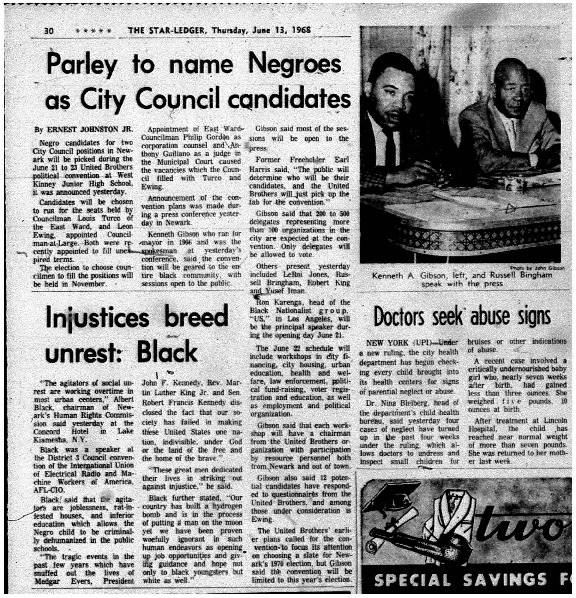

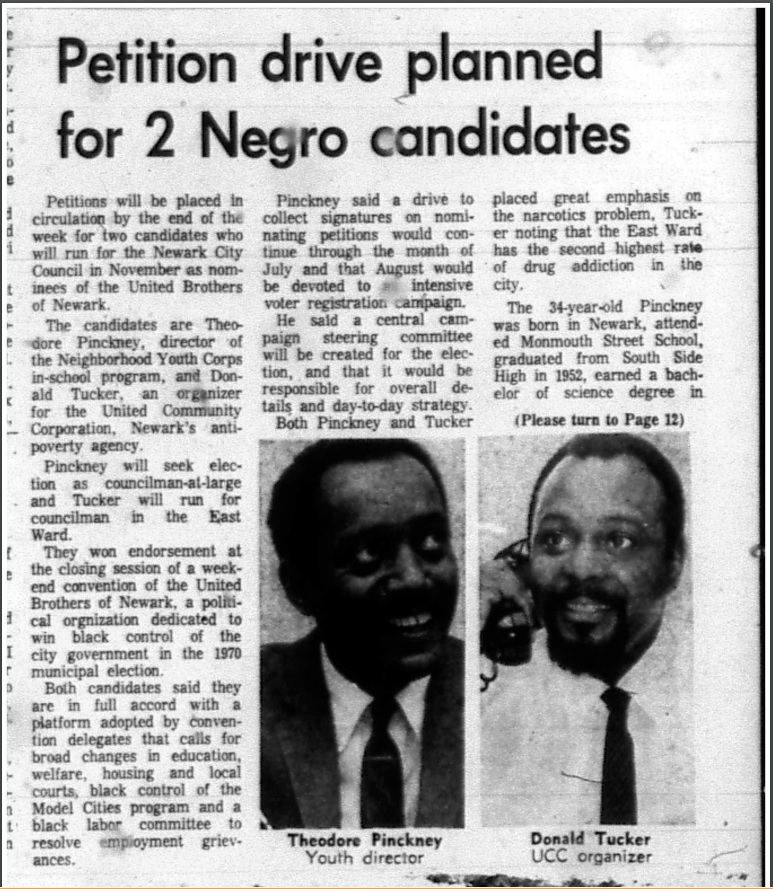

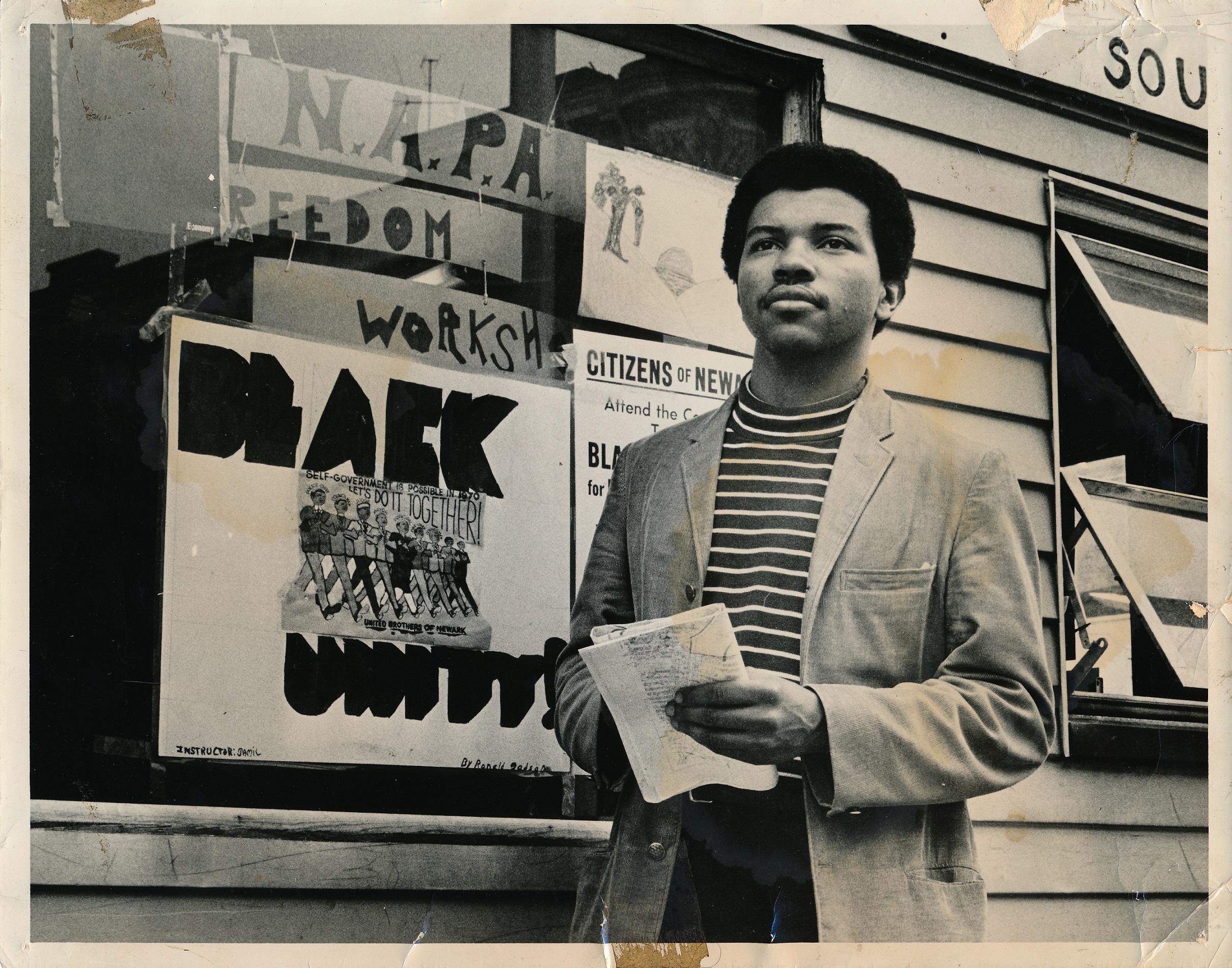

Some of the people invited were involved in most of the key resistance efforts in Newark in the late 1960s: Donald Tucker, Earl Harris, Eulis “Honey” Ward, Harry Wheeler, Junius Williams, and Louise Epperson, all coming fresh from the Medical School fight and/or the Parker Callaghan struggle. Ken Gibson was not a radical or a militant, but he had been involved with the BICC (the coalition of business and community leaders convened to bring jobs for black people in downtown retail stores and other places) and the United Community Corporation (the War on Poverty). Additionally, he ran for Mayor in 1966 and got 15,000 votes. Ted Pinckney was active in the UCC; Russell Bingham was a protégé of Honey Ward. Harold Wilson, John Bugg, and others were personal friends of Baraka. This group would meet each Sunday to organize and develop this “Black United Front.”

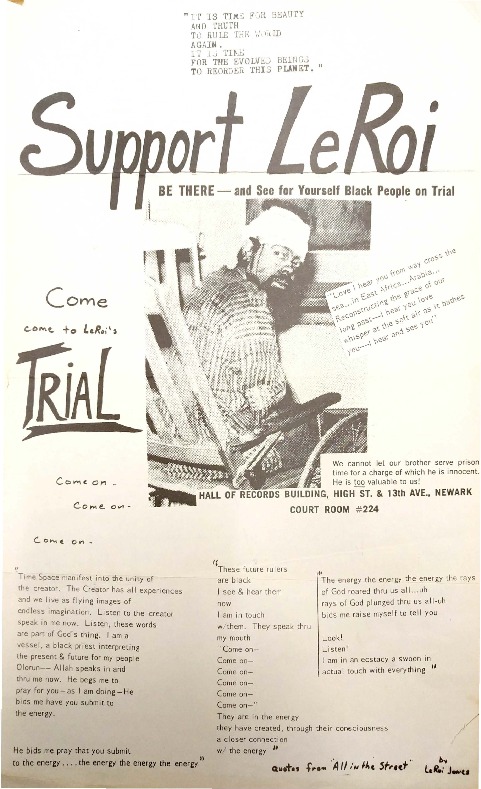

Baraka introduced a security force to these Sunday meetings. First came Kamiel Wadud and his men. Kamiel was a Sunni Muslim affiliated with a man named Hajj Heesham Jaaber—an associate of the late Malcolm X. Baraka said in his autobiography that it was Heesham who first changed his name from LeRoi Jones to Ameer Barakat.

But soon thereafter another group was presented as security. Black Community Development and Defense (BCD) was headed by Pan Africanist Balozi Zayd Muhammad, and karate expert Mfundishi Maasi, both of whom were from East Orange.

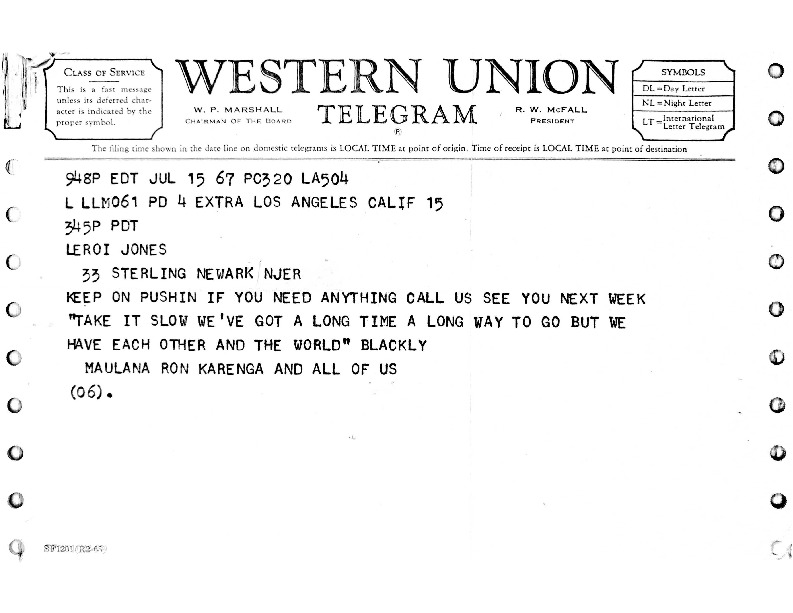

Baraka admired Ron Karenga, a cultural nationalist in California with an organization called “US.” It was Karenga who changed his name from Ameer Barakat, to Amiri Baraka.

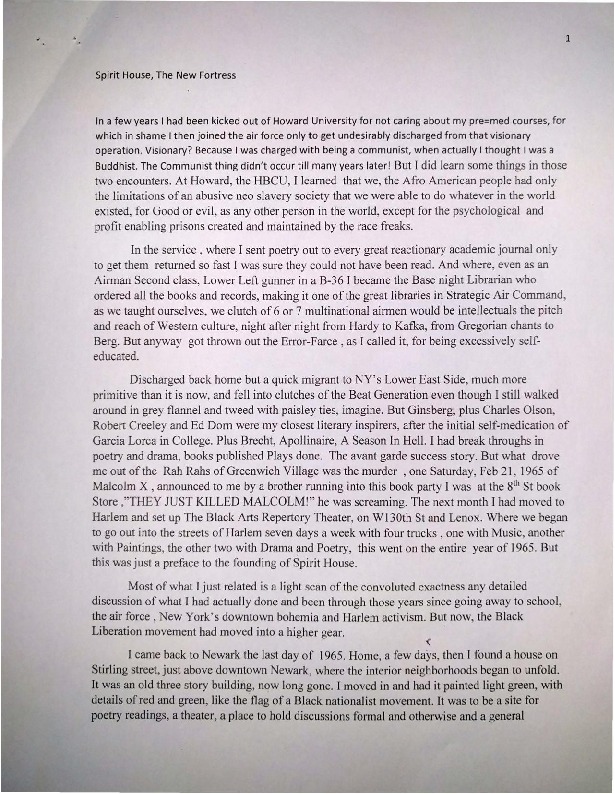

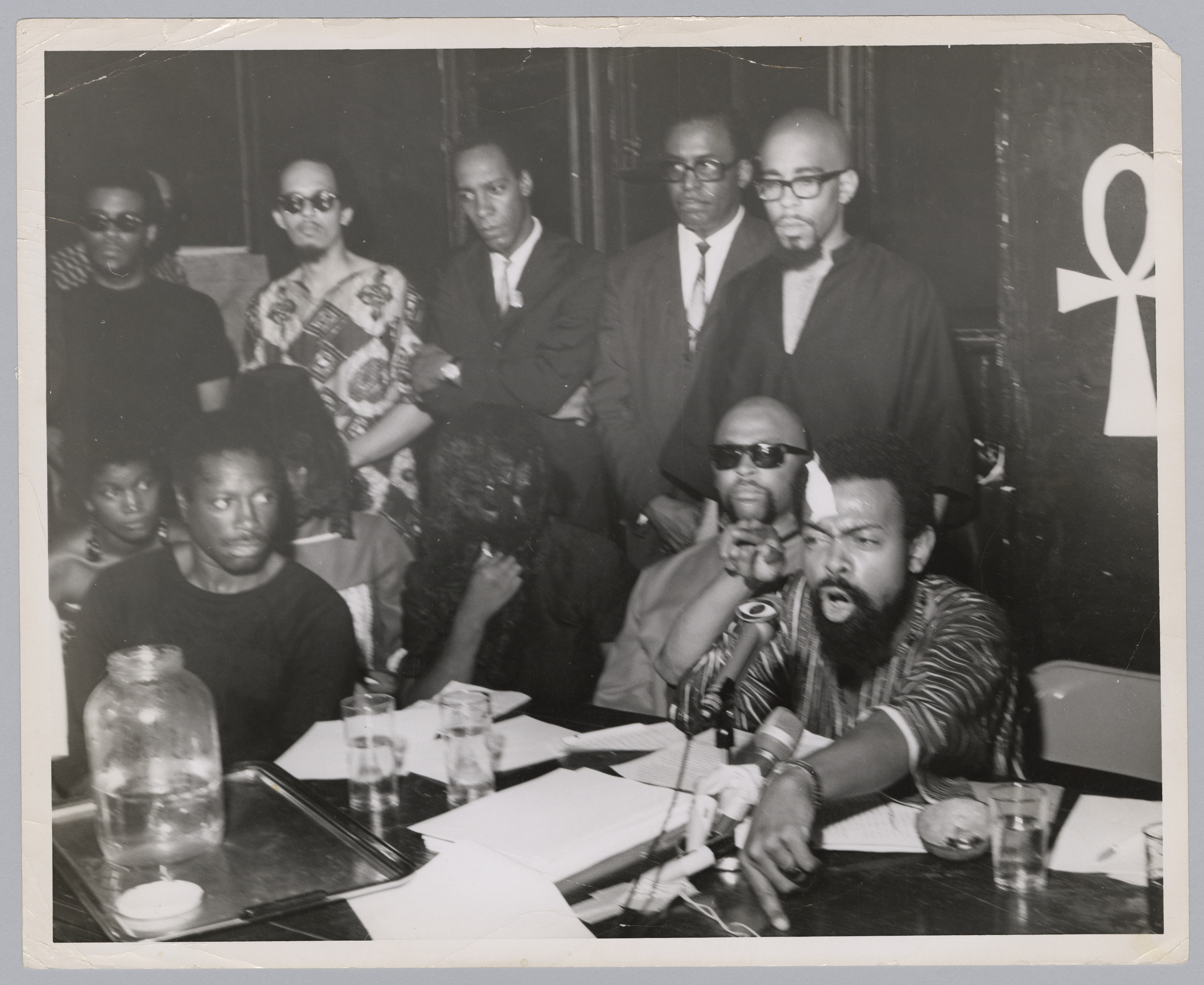

Karenga’s style of organization was based on discipline and tight control by a central leader. Under the tutelage of Karenga, Baraka began to build that kind of organization in Newark, with the help of the BCD. Baraka envisioned the Committee for Unified Newark as a “larger united front” composed of Baraka’s Spirit House Movers and Players, the BCD, and the United Brothers.

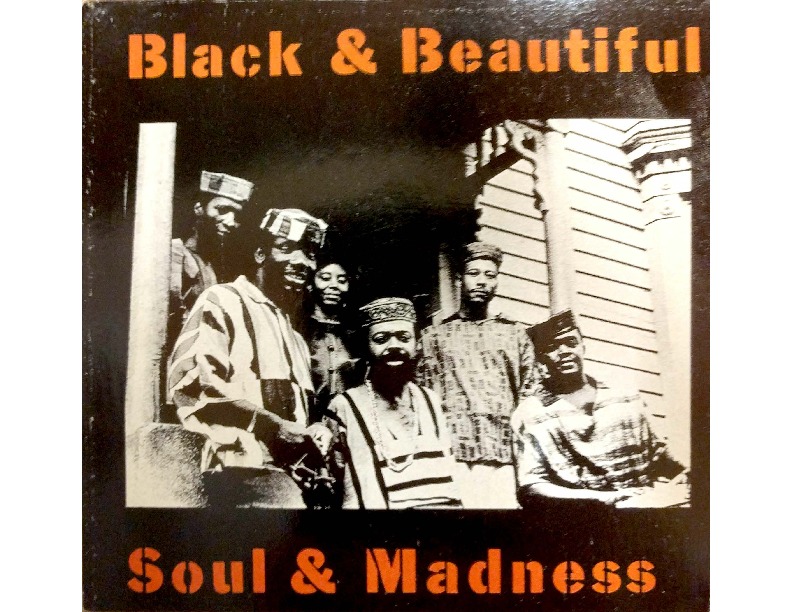

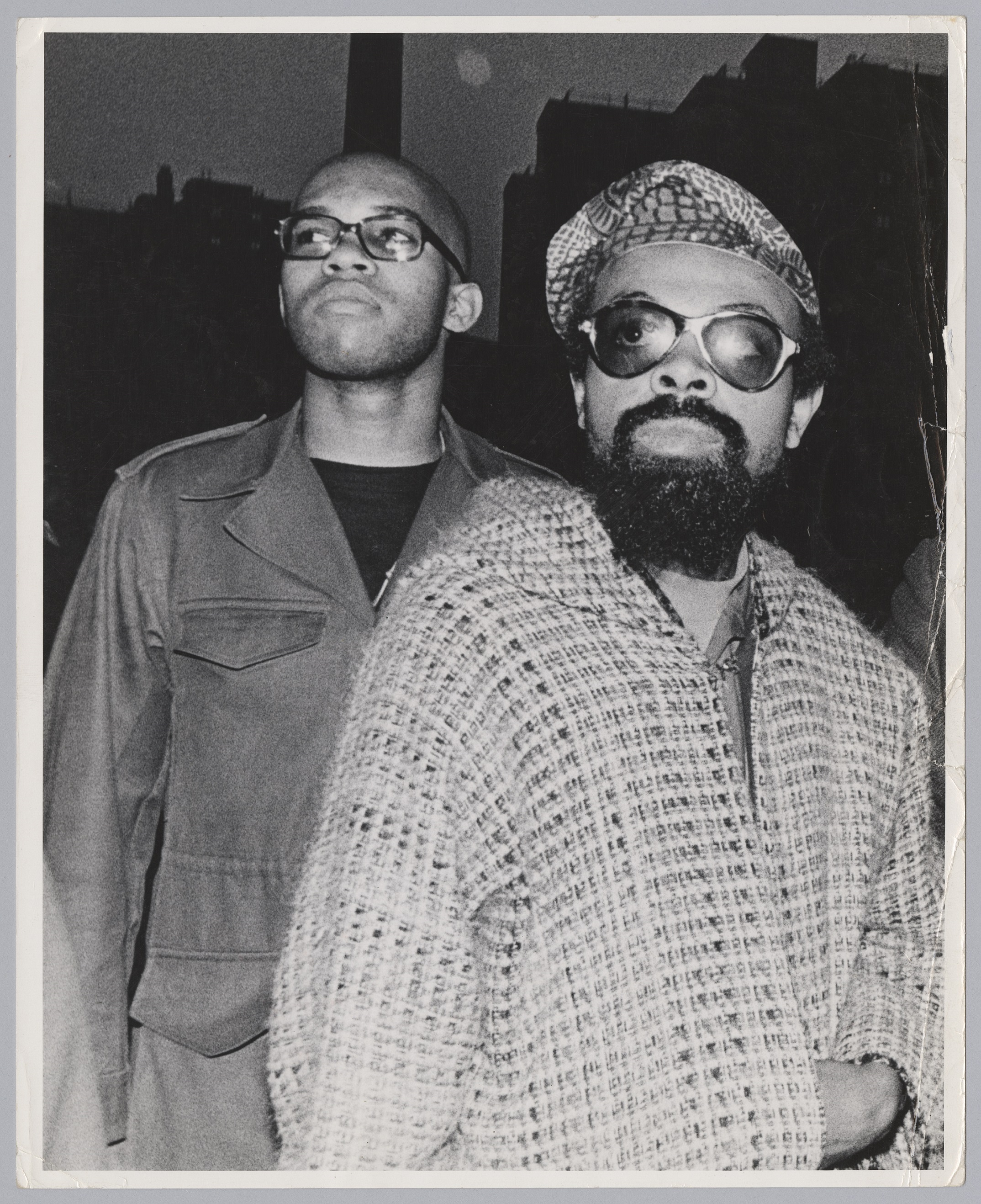

This change didn’t happen overnight, but over about a several month period. More and more elements of Karenga’s “cultural revolution” were added to the organization. There was an African identity assumed by those who were Baraka’s most loyal followers, which required African garb, and the regular use of Swahili, the trade language amongst Africans in East Africa. Discipline was a part of the culture. The women, also in African garb, were expected to serve in disciplined fashion. Some of the members in CFUN were given Afrocentric names by Baraka or Karenga, and Baraka also married people and named babies.

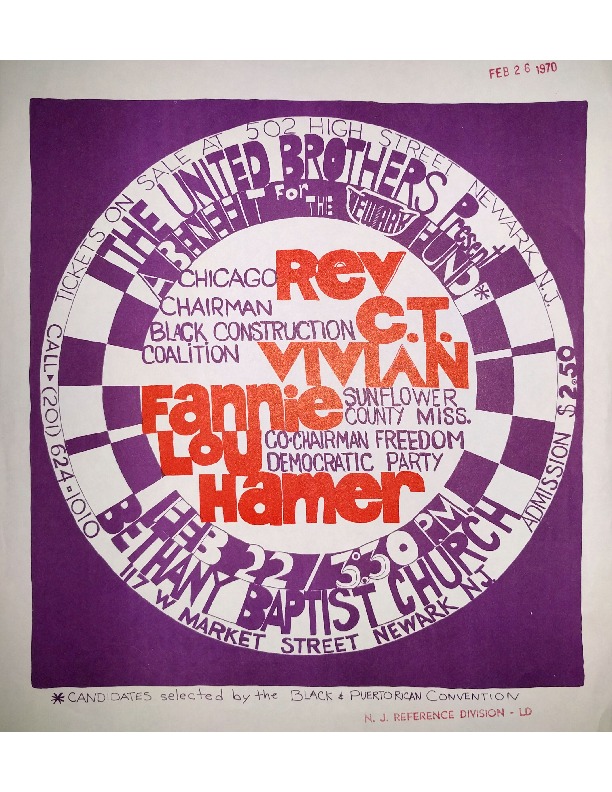

A building at 502 High Street became the headquarters for CFUN. The Housing Authority gave its use to Baraka, because one day he went over and made the demand for the building. It was a beautiful building acquired by the Housing Authority through urban renewal, next to the St. Benedict’s High School on High Street near the corner of Springfield Avenue.

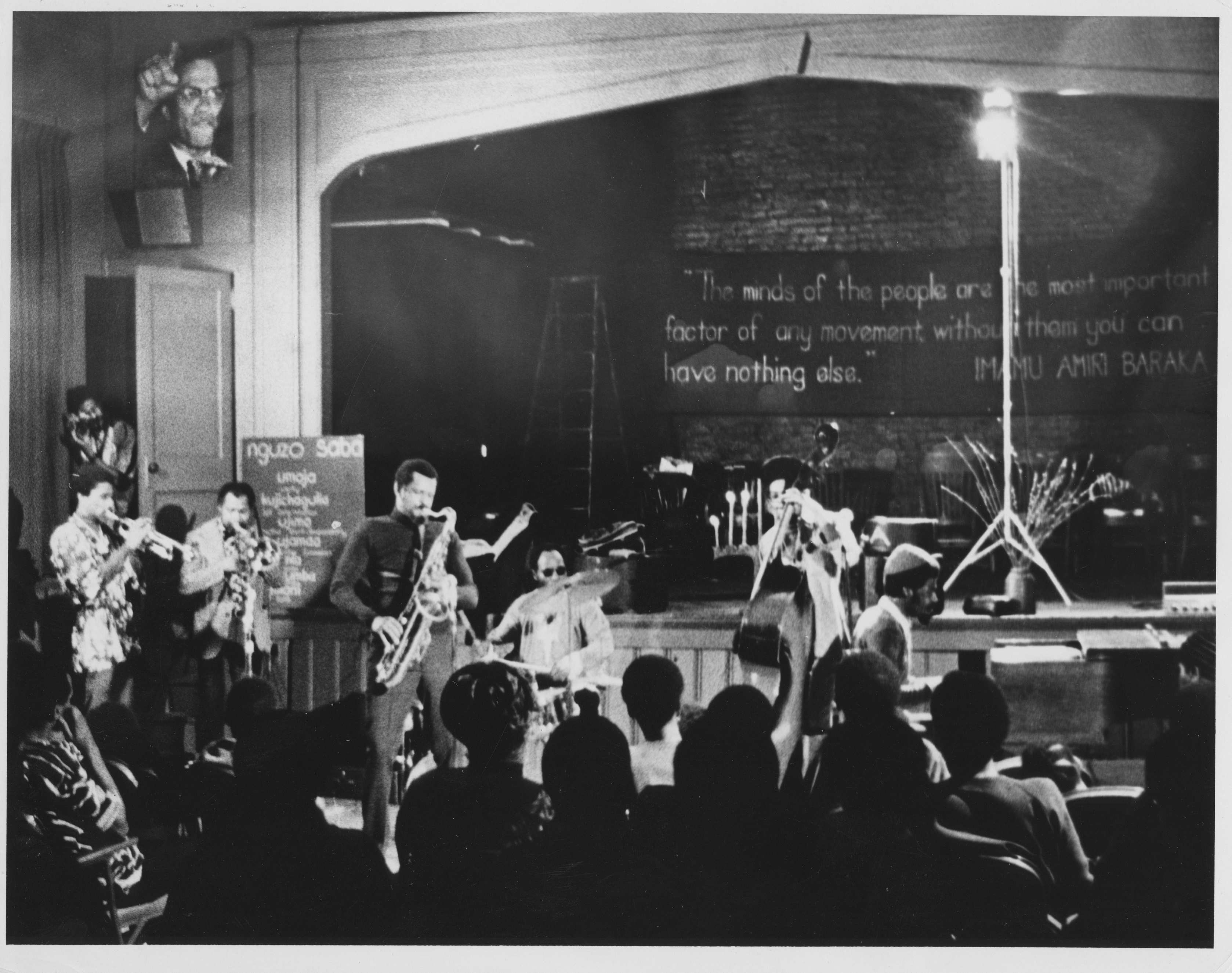

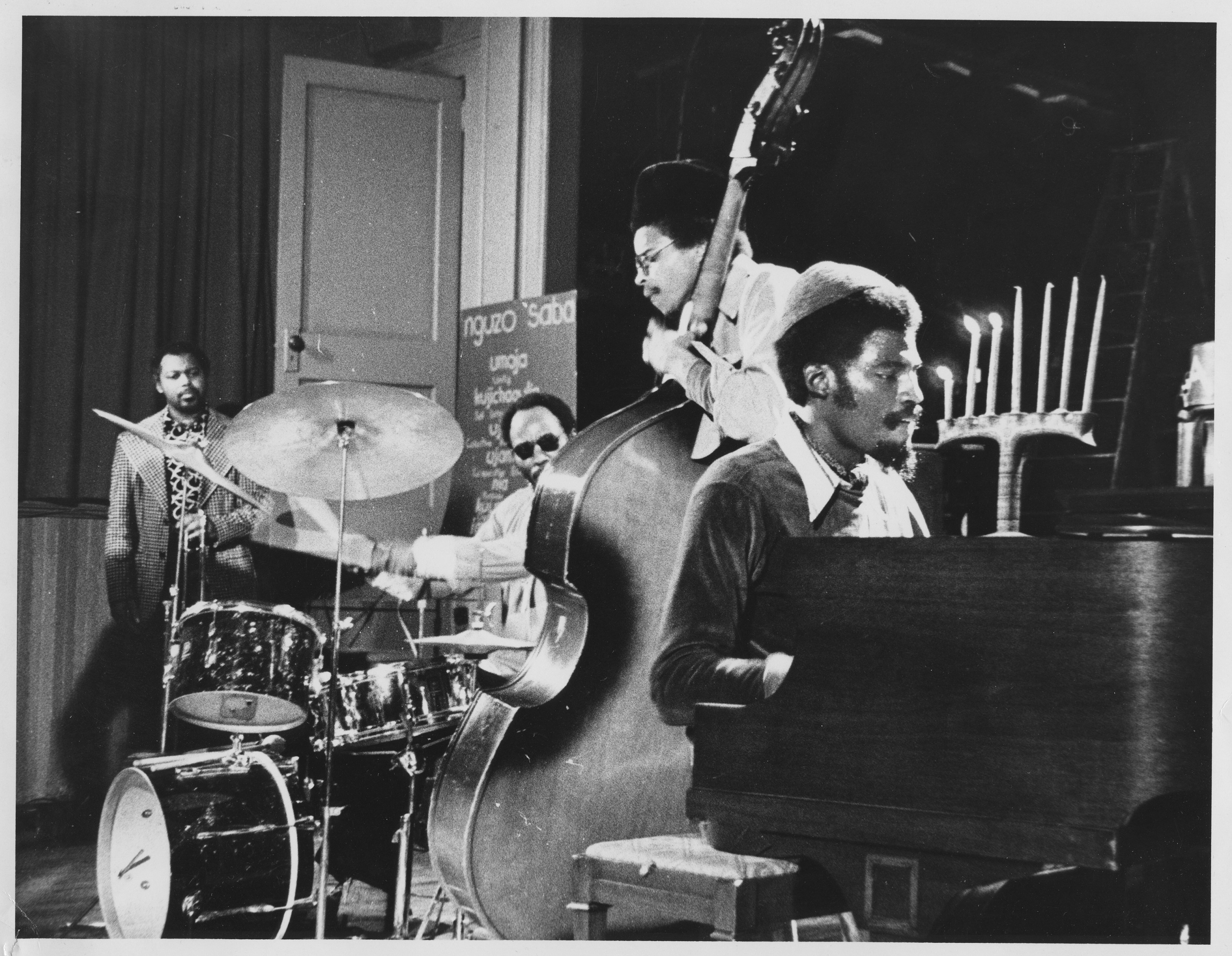

There were “Soul Sessions” at CFUN headquarters, also called the “Hekalu,” which were very much tailored to make the African connection. The brothers and sisters wore African garb, and danced to African music. Baraka and Karenga, when he was in town, gave spirited speeches focusing on cultural identity and politics. They were held on Sunday afternoons and lasted into the early evenings.

The merger of interests between cultural nationalism (CFUN) and mayoral politics (United Brothers) was a volatile coalition that survived the election of Ken Gibson as Mayor in 1970. Not everyone who was a part of the United Brothers, though, was a cultural nationalist.

In November of 1967, two friends of Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), John Bugg and Harold Wilson, sent out a letter inviting a small group of African American leaders to meet at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Newark on December 8th. Twelve men and one woman were asked to be a part of the development of a “Black United Front” to take power in the election of 1970.

Some of the people invited were involved in most of the key resistance efforts in Newark in the late 1960s: Donald Tucker, Earl Harris, Eulis “Honey” Ward, Harry Wheeler, Junius Williams, and Louise Epperson, all coming fresh from the Medical School fight and/or the Parker Callaghan struggle. Ken Gibson was not a radical or a militant, but he had been involved with the BICC (the coalition of business and community leaders convened to bring jobs for black people in downtown retail stores and other places) and the United Community Corporation (the War on Poverty). Additionally, he ran for Mayor in 1966 and got 15,000 votes. Ted Pinckney was active in the UCC; Russell Bingham was a protégé of Honey Ward. Harold Wilson, John Bugg, and others were personal friends of Baraka. This group would meet each Sunday to organize and develop this “Black United Front.”

Baraka introduced a security force to these Sunday meetings. First came Kamiel Wadud and his men. Kamiel was a Sunni Muslim affiliated with a man named Hajj Heesham Jaaber—an associate of the late Malcolm X. Baraka said in his autobiography that it was Heesham who first changed his name from LeRoi Jones to Ameer Barakat.

But soon thereafter another group was presented as security. Black Community Development and Defense (BCD) was headed by Pan Africanist Balozi Zayd Muhammad, and karate expert Mfundishi Maasi, both of whom were from East Orange.

Baraka admired Ron Karenga, a cultural nationalist in California with an organization called “US.” It was Karenga who changed his name from Ameer Barakat, to Amiri Baraka.

Karenga’s style of organization was based on discipline and tight control by a central leader. Under the tutelage of Karenga, Baraka began to build that kind of organization in Newark, with the help of the BCD. Baraka envisioned the Committee for Unified Newark as a “larger united front” composed of Baraka’s Spirit House Movers and Players, the BCD, and the United Brothers.

This change didn’t happen overnight, but over about a several month period. More and more elements of Karenga’s “cultural revolution” were added to the organization. There was an African identity assumed by those who were Baraka’s most loyal followers, which required African garb, and the regular use of Swahili, the trade language amongst Africans in East Africa. Discipline was a part of the culture. The women, also in African garb, were expected to serve in disciplined fashion. Some of the members in CFUN were given Afrocentric names by Baraka or Karenga, and Baraka also married people and named babies.

A building at 502 High Street became the headquarters for CFUN. The Housing Authority gave its use to Baraka, because one day he went over and made the demand for the building. It was a beautiful building acquired by the Housing Authority through urban renewal, next to the St. Benedict’s High School on High Street near the corner of Springfield Avenue.

There were “Soul Sessions” at CFUN headquarters, also called the “Hekalu,” which were very much tailored to make the African connection. The brothers and sisters wore African garb, and danced to African music. Baraka and Karenga, when he was in town, gave spirited speeches focusing on cultural identity and politics. They were held on Sunday afternoons and lasted into the early evenings.

The merger of interests between cultural nationalism (CFUN) and mayoral politics (United Brothers) was a volatile coalition that survived the election of Ken Gibson as Mayor in 1970. Not everyone who was a part of the United Brothers, though, was a cultural nationalist.

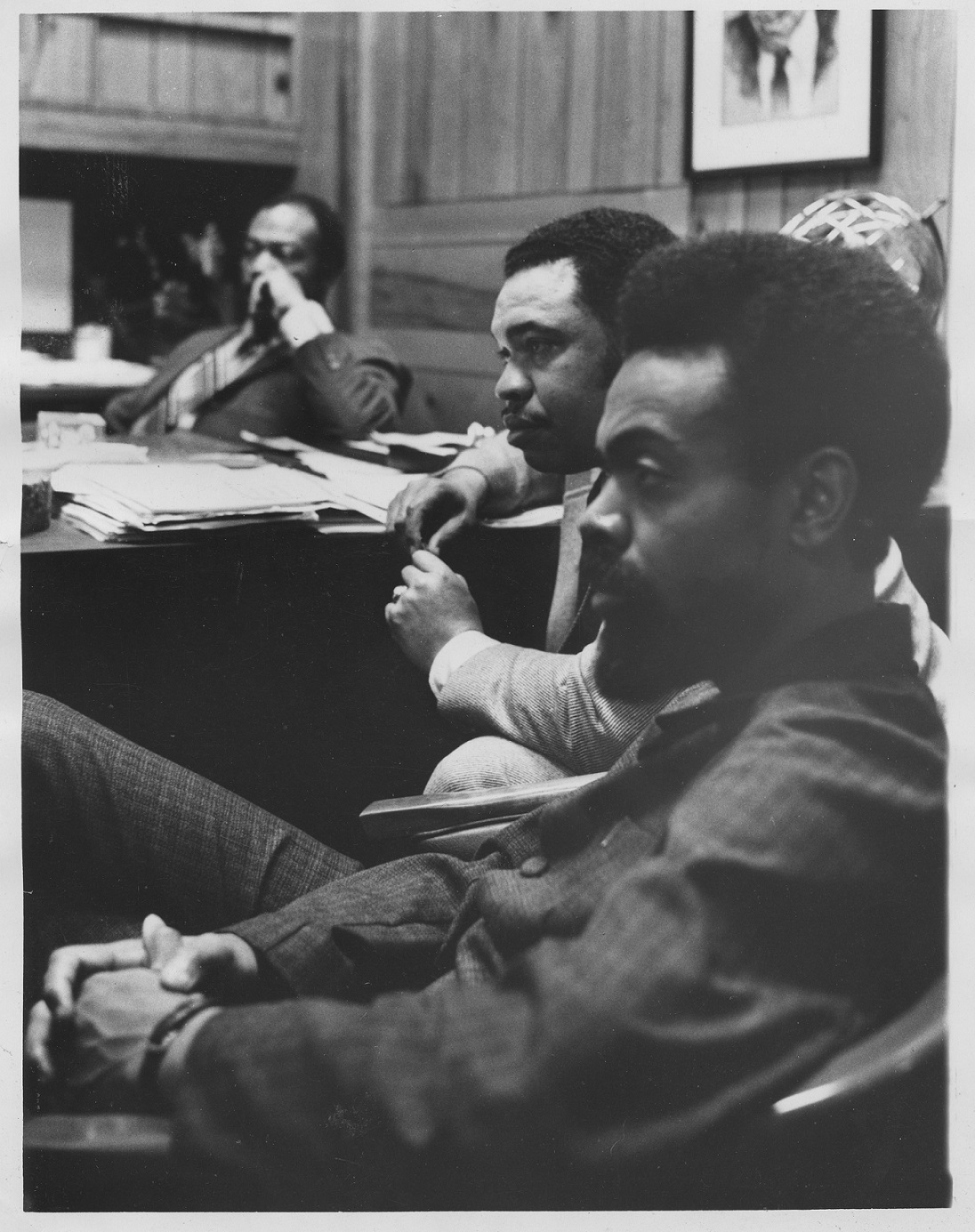

Clip from interview with poet and activist Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), in which he discusses the formation of the United Brothers and Committee for Unified Newark. The United Brothers was a coalition of Black leaders in Newark organized to develop a “Black United Front” to take power in the mayoral election of 1970. This coalition evolved into the Committee for Unified Newark, a “larger united front,” consisting of the United Brothers, the Spirit House Movers and Players, and Black Community Development and Defense. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from an interview with Newark Area Planning Association (NAPA) and Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) member Junius Williams, in which he discusses the emergence of the United Brothers in Newark. The United Brothers was a coalition of Black leaders in Newark organized to develop a “Black United Front” to take power in the mayoral election of 1970. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Explore The Archives