Predictions

Warning Signs: Newark and the Long, Hot Summers

Beginning in Harlem in July of 1964, a series of urban rebellions swept across the nation, signaling a new direction in the national Civil Rights Movement. While civil rights organizations escalated their protests throughout the South, northern Black communities, largely segregated in urban ghettoes, had been actively organizing to gain an equal share in economic, political, and social power structures. As urban Black communities in the North protested discrimination in employment, education, housing, and law enforcement, they were met by increasingly hostile resistance from city governments and law enforcement agencies. In Harlem, the fatal shooting of 15-year-old African-American student James Powell by a white off-duty police lieutenant marked the climax of decades of police brutality and triggered the outbreak of the first of several urban rebellions in the North that spread almost immediately to Rochester, NY; Philadelphia, PA; Chicago, IL; Cleveland, OH; and nearby Jersey City, Paterson, Elizabeth, and Passaic, NJ.

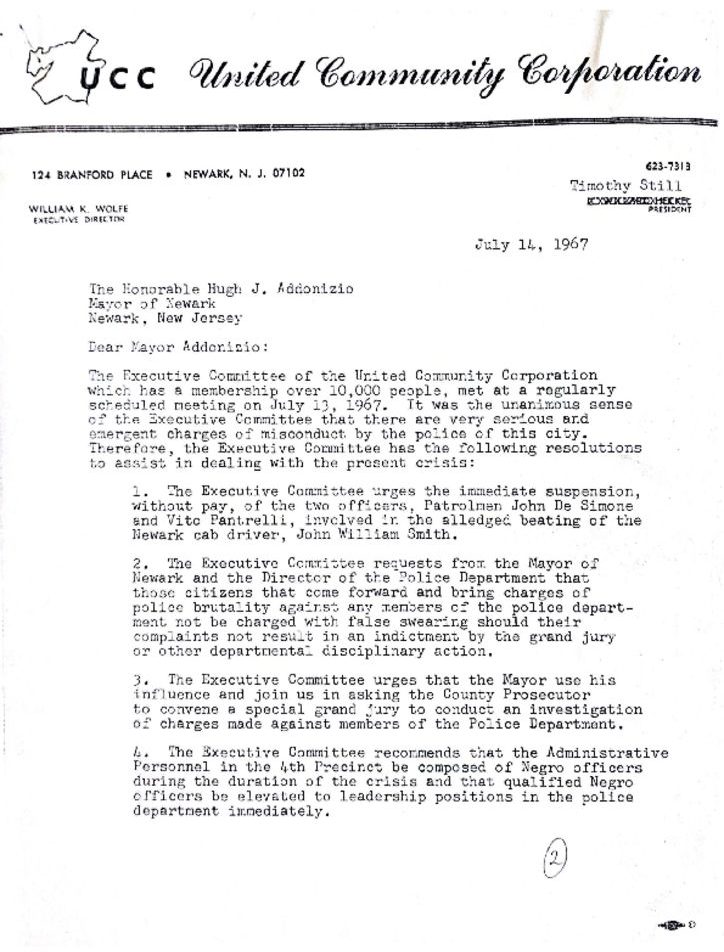

The underlying issues of institutional racism that set the stage for the outbreak of “riots” or “rebellions” in these cities were much the same as those facing African American communities in Newark. For several years, organizations such as the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP), the United Community Corporation (UCC), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and many others, had been protesting issues such as discrimination in housing, education, and employment, as well as police brutality. With tensions growing over the gradual pace of the Civil Rights Movement throughout the nation and “urban unrest” creeping steadily closer to Newark, city officials and Newark communities teetered on the edge of conflict between 1964 and 1967.

For some, the absence of “race riots” in Newark in 1964 was “evidence of alert, intelligent and forward-looking leadership” in the city. For others, however, it was a wonder that Newark’s rebellion in 1967 didn’t come sooner. Speaking in the Central Ward in 1966, SNCC Chairman Stokely Carmichael told the crowd gathered in the predominantly African American community that they ‘should already have taken Newark over because it belongs to you.’ For those most directly affected by institutional racism in Newark, the city “had in fact become a social volcano, ready to erupt.”

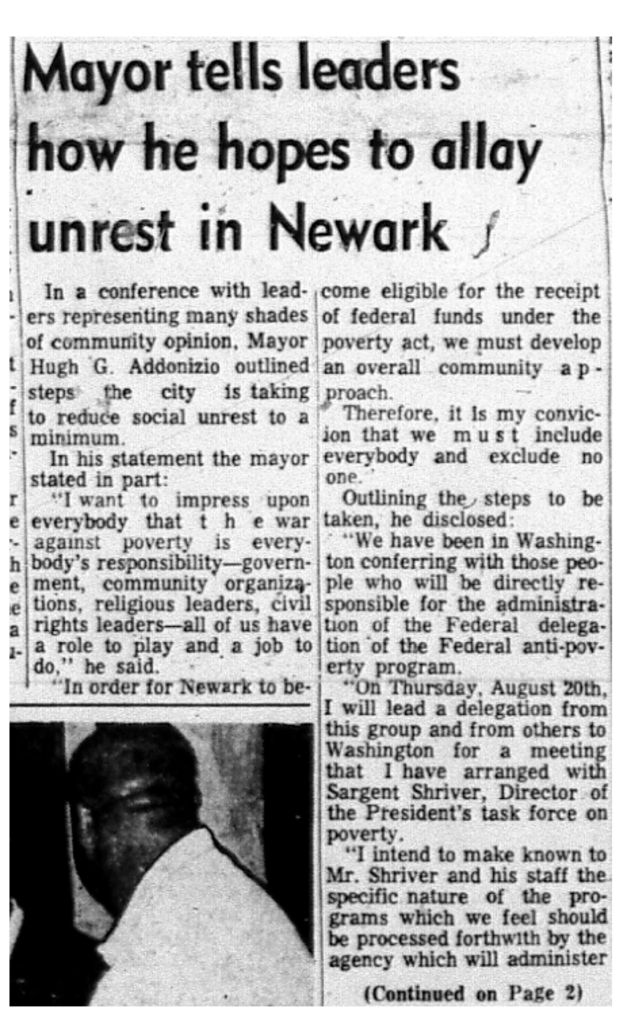

Article from the New Jersey Afro-American on August 22, 1964 in which Mayor Addonizio describes his plans to address similar issues in Newark that led to violent protest in nearby Paterson, Elizabeth, and Jersey City. — Credit: New Jersey Afro-American, Newark Public Library

Explore The Archives

Clip from the documentary film “Newark: The Slow Road Back,” in which community leader Bob Curvin describes the national and local climates leading up to the outbreak of the 1967 Newark rebellion. — Credit: Sandra King

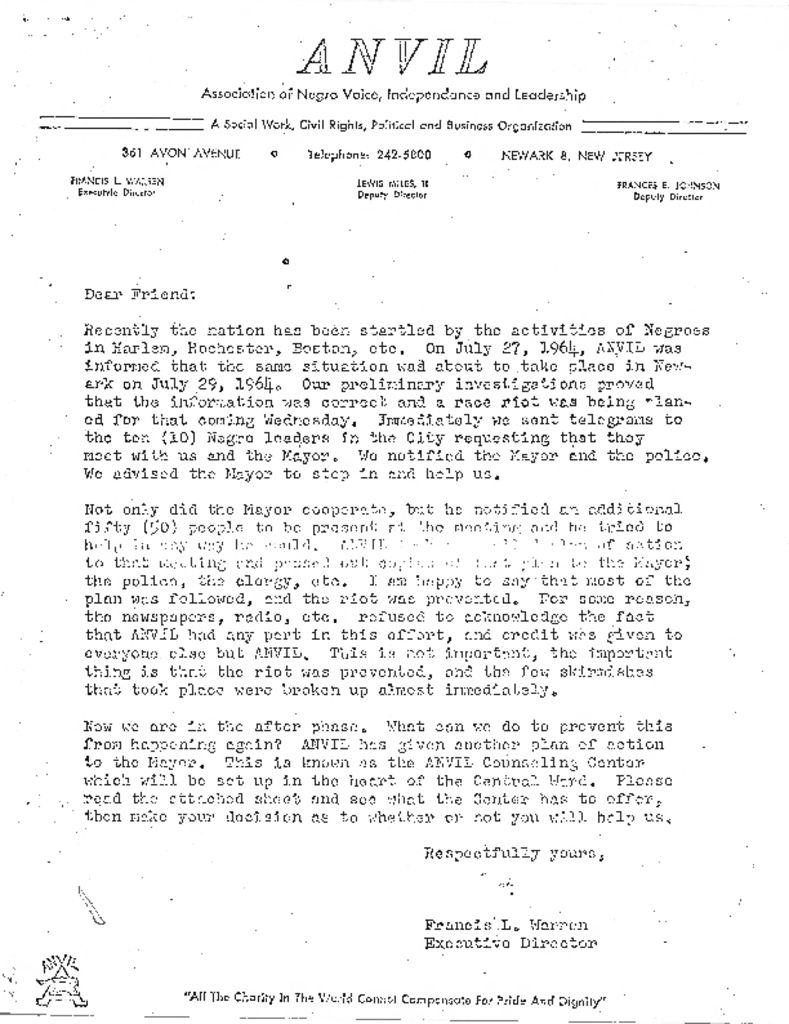

Letter from Francis Warren, Executive Director of ANVIL, claiming that a “race riot” was being planned in Newark shortly after the outbreak of rebellions in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant in July 1964. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Letter to the Editor of the New Jersey Afro-American on August 15, 1964. The author praises the city’s “forwardlooking leadership” and claims the “colored community” is “grateful for the tremendous progress being made on all fronts…in the fields of human rights…” — Credit: Newark Public Library

Memo from William Mercer, coordinator of the Business Industrial Coordinating Committee (BICC) to the BICC Executive Committee, in which he describes the City of Newark as “ready to explode.” Mercer cites some of the causes of heightened tension, including: the Medical School fight, Parker-Callaghan dispute, and the National Black Power Conference planned for July. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Parker-Callaghan Fight:

“Two big protests set the tone for the summer of 1967. One was called the Parker-Callaghan fight. In early 1967, Mayor Addonizio urged the appointment of Councilman James T. Callaghan as the secretary (business administrator) to the Board of Education. Callaghan only had a high school degree. On the other hand, the NAACP, under new leadership of Sally Carroll, as well as Fred Means, the president of the Negro Educators of Newark, and the vast majority of black organizations and individuals supported Wilbur Parker, the first black certified public accountant in the state of New Jersey, and the city budget director, for the job.

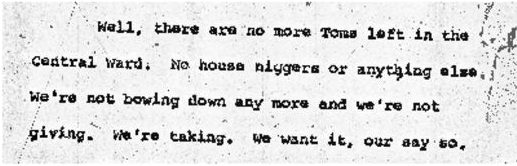

Many community advocates signed up and spoke at the Board of Education meeting, while hundreds of us cheered them on at a meeting that lasted until 3:00 AM. Because of the uproar, Addonizio backed down, and his appointed board decided to keep Arnold Hess, the man already in the job. But the damage had been done; tensions were at a fever pitch. And there was unity from across the full spectrum of the black community, so much so that the House Negroes shut up and in some cases defected to us.”

-Junius Williams, Newark Community Union Project (NCUP)

“For several months in 1967, at every school board meeting, CORE and other groups, also backed by white community leaders from the South Ward, as well as church leaders, staged vehement protests that disrupted the conduct of board business. At the board of education meeting on June 28, 1967, when the appointment was to be made, civil rights activists occupied the seats of the board of education members while they adjourned to caucus on their deliberations. The meeting was terminated. Neither Callaghan or Parker was appointed.”

-Robert Curvin, Newark Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

Clip from an interview with United Community Corporation (UCC) member Sharpe James, in which he explains the anger of Newark’s Black communities over the Parker-Callaghan Fight. The Parker-Callaghan Fight is credited as one of the precipitating factors of the 1967 Newark rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from an interview with United Community Corporation member Mary Smith, in which she describes the Parker-Callaghan Fight and how it influenced the outbreak of the 1967 Newark rebellion. The Parker-Callaghan Fight is credited as one of the precipitating factors of the 1967 Newark rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Explore The Archives

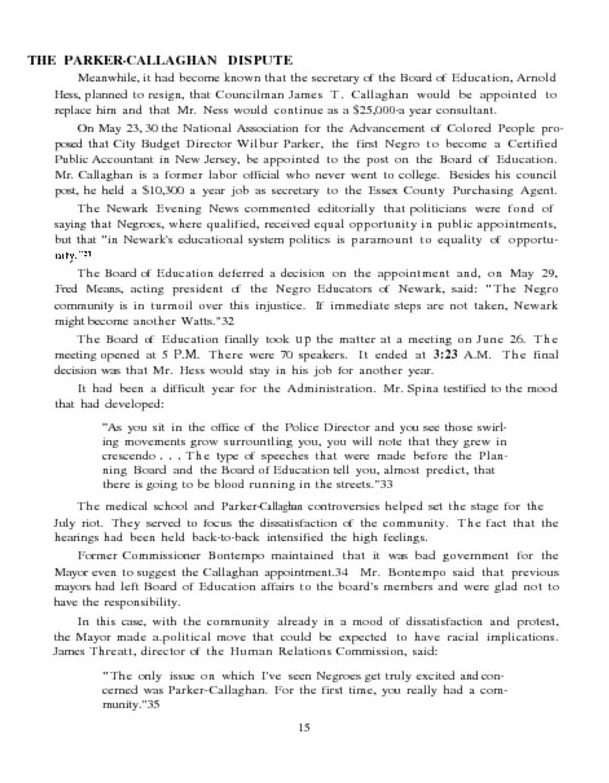

Excerpt from the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder regarding the influence of the Parker-Callaghan fight on the 1967 Newark rebellion. The excerpt includes testimony from Police Director Dominick Spina saying ‘The types of speeches that were made before the Planning Board and the Board of Education tell you, almost predict, that there is going to be blood running in the streets.’ — Credit: Report for Action: Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder, State of New Jersey

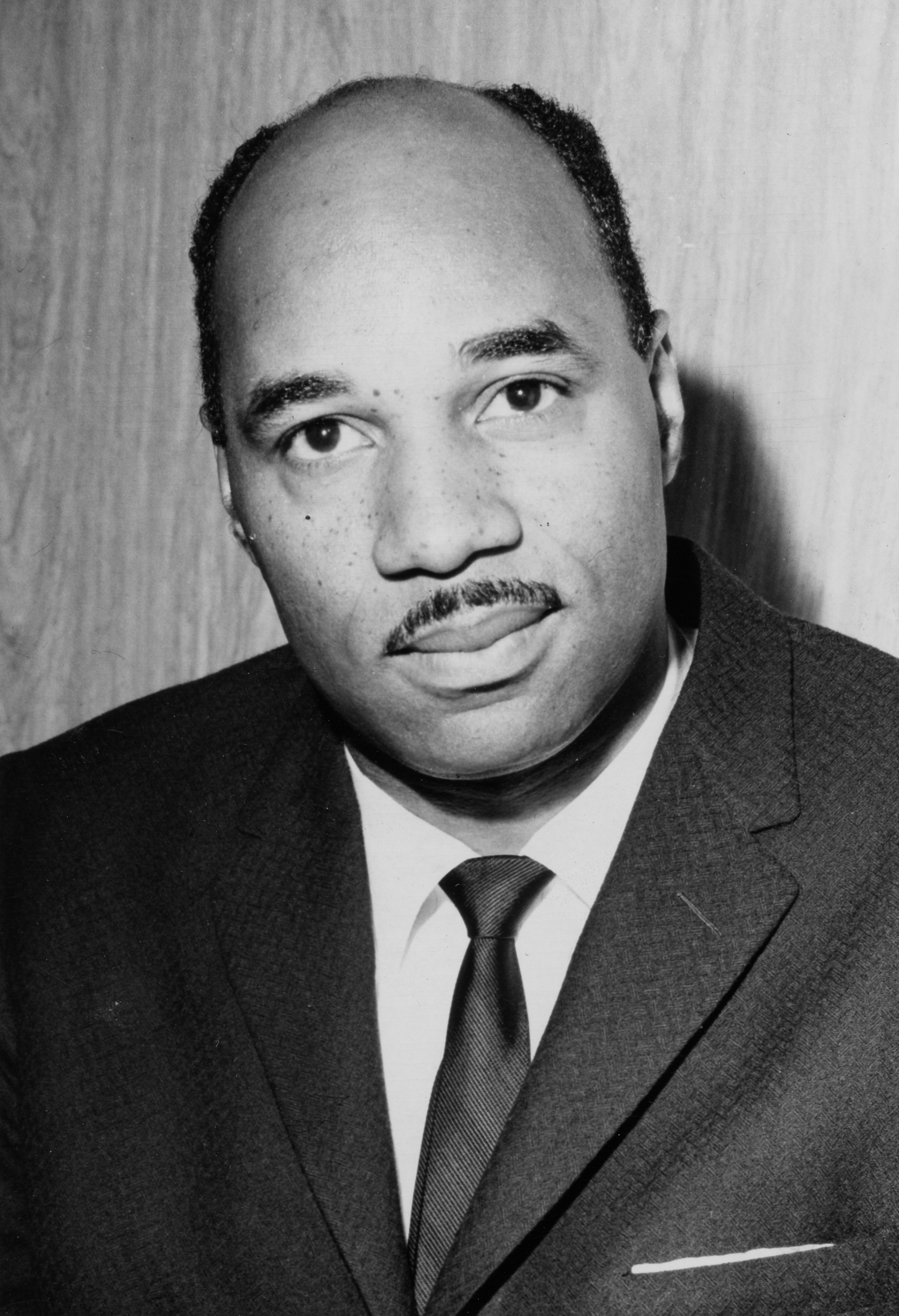

Portrait of Wilbur Parker, who was the favorite of Newark’s African American community to replace Arnold Hess for the position of Secretary of the Board of Education. — Credit: Newark Public Library

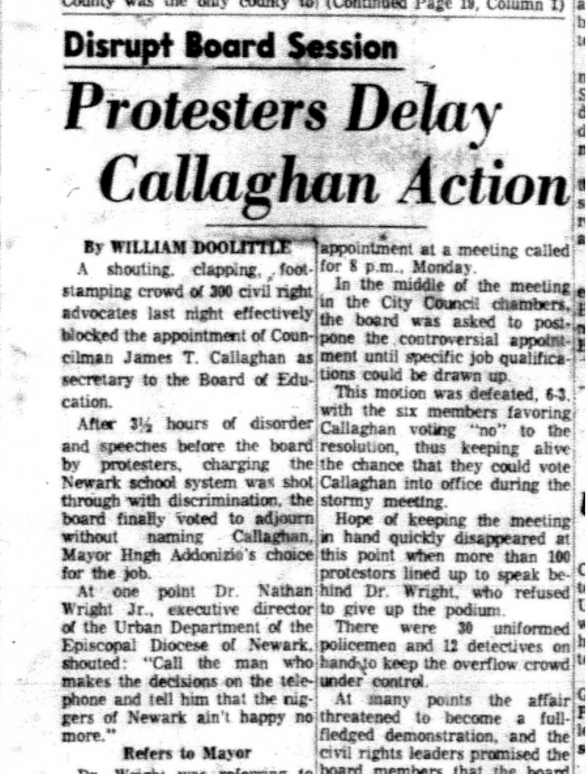

Article from the Newark Evening News on May 24, 1967 covering the protests at a Board of Education meeting the previous night to appoint James Callaghan as Secretary of the Board of Education. The protests waged by some “300 civil rights advocates” who supported the appointment of Wilbur Parker, a highly qualified African American accountant, effectively blocked the appointment during the meeting. — Credit: Newark Public Library

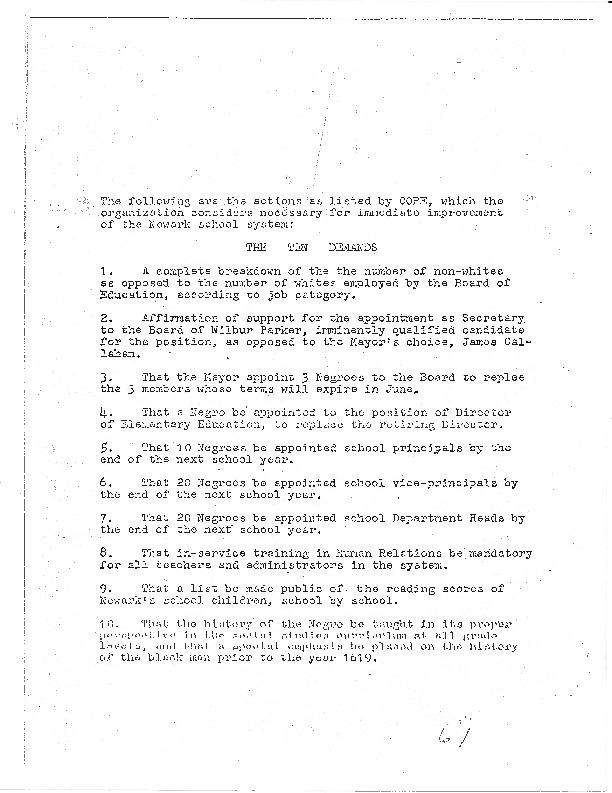

List of educational demands presented by the Newark-Essex Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to the Board of Education at their meeting on May 29, 1967. The May 29th meeting came just days after protestors shut down an earlier Board of Education meeting over Mayor Addonizio’s planned appointment of James Callaghan as Secretary of the Board of Education over Wilbur Parker, a highly qualified African American accountant. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Medical School Fight:

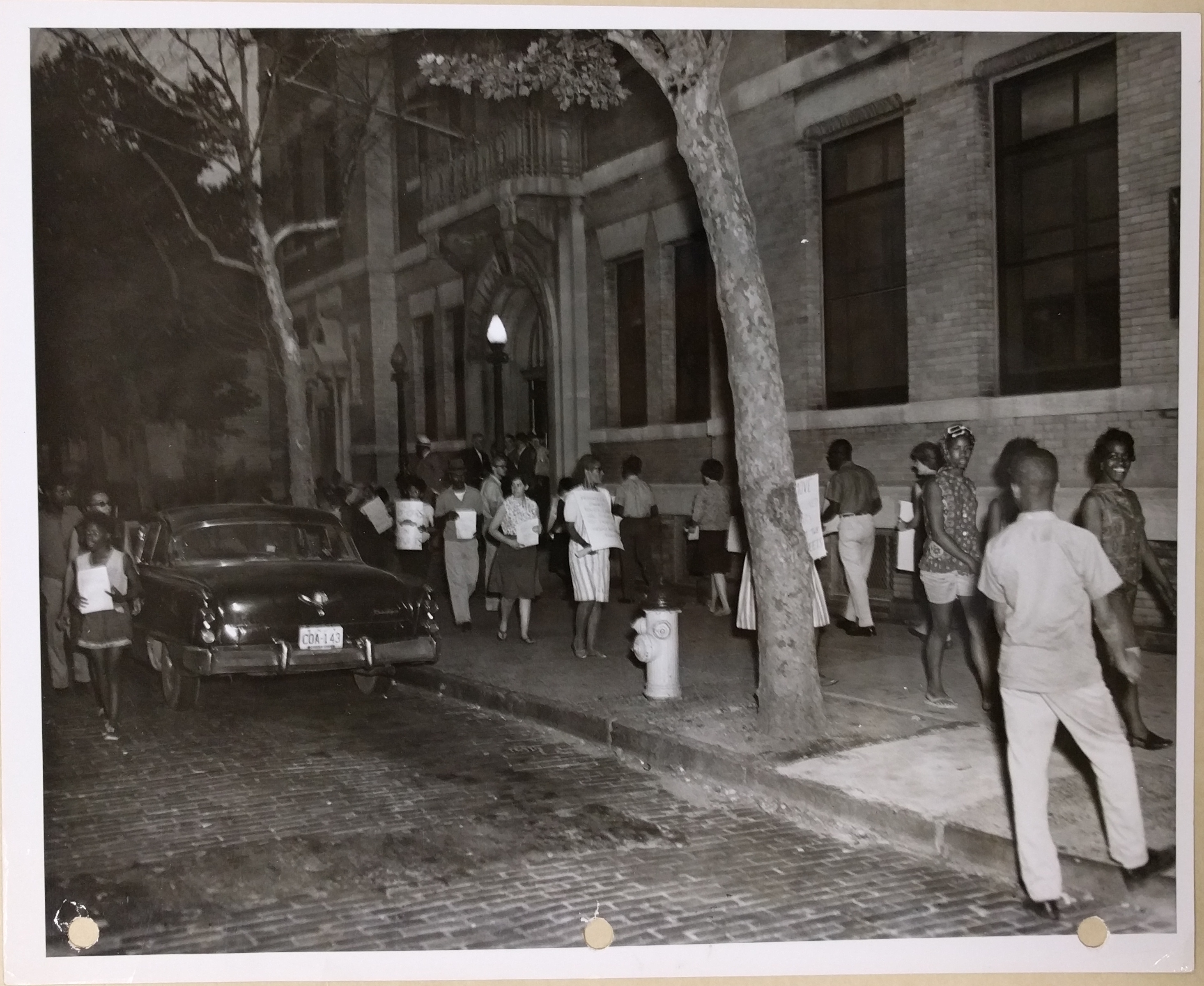

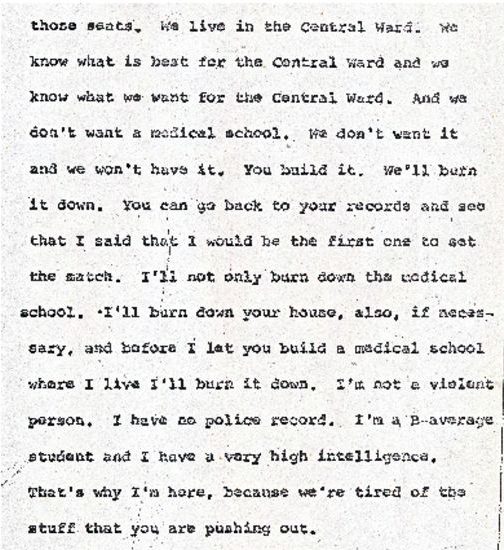

“And then there was the Medical School Fight, which came to an initial climax at the June 1967 “blight hearings,” which, under New Jersey law, were needed to take private land through urban renewal on behalf of the New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry (later known as the University of Medicine and Dentistry, UMDNJ). Mayor Addonizio initially offered the school two hundred acres of land in the Central Ward, which would have displaced 22,000 mostly black people. Black folks and our supporters said “Hell no,” and flocked to a series of meetings at city hall before the Central Planning Board. Like Parker-Callaghan, the local leadership lined up and spoke in the City Council chamber, led by George Richardson; Jimmy Hooper, chairman of CORE; Louise Epperson and Harry Wheeler of the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal. Someone named Colonel Hassan from the Black Man’s Liberation Army, originally from Washington, DC, provided the magic moment: one of his lieutenants snatched the record of the proceedings. There was near bedlam at the meeting. That meeting was turned out, but more meetings were scheduled to carry out the process. More and more people started coming out to see what was going to happen next…”

-Junius Williams, Newark Community Union Project (NCUP)

References:

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

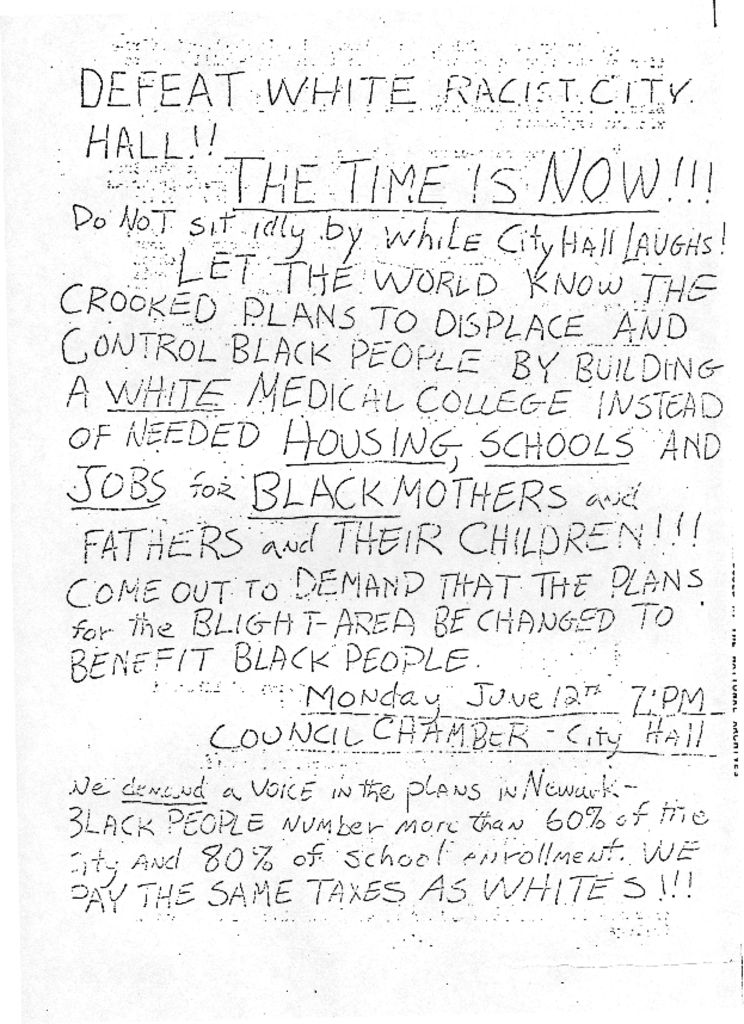

Flyer distributed in the Central Ward to encourage community members to encourage community unity to protest the seizure of land for the construction of a medical school. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Explore The Archives

Clip from an interview with community leader George Richardson, in which he explains the Medical School Fight and the strategy of filibustering the Blight Hearings. The Medical School Fight and contentious Blight Hearings are credited as one of the precipitating factors of the 1967 Newark rebellion. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from an interview with NCUP member Junius Williams, in which he describes the significance and scenes of the Medical School Blight Hearings. The Medical School Fight and contentious Blight Hearings are credited as one of the precipitating factors of the 1967 Newark rebellion. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

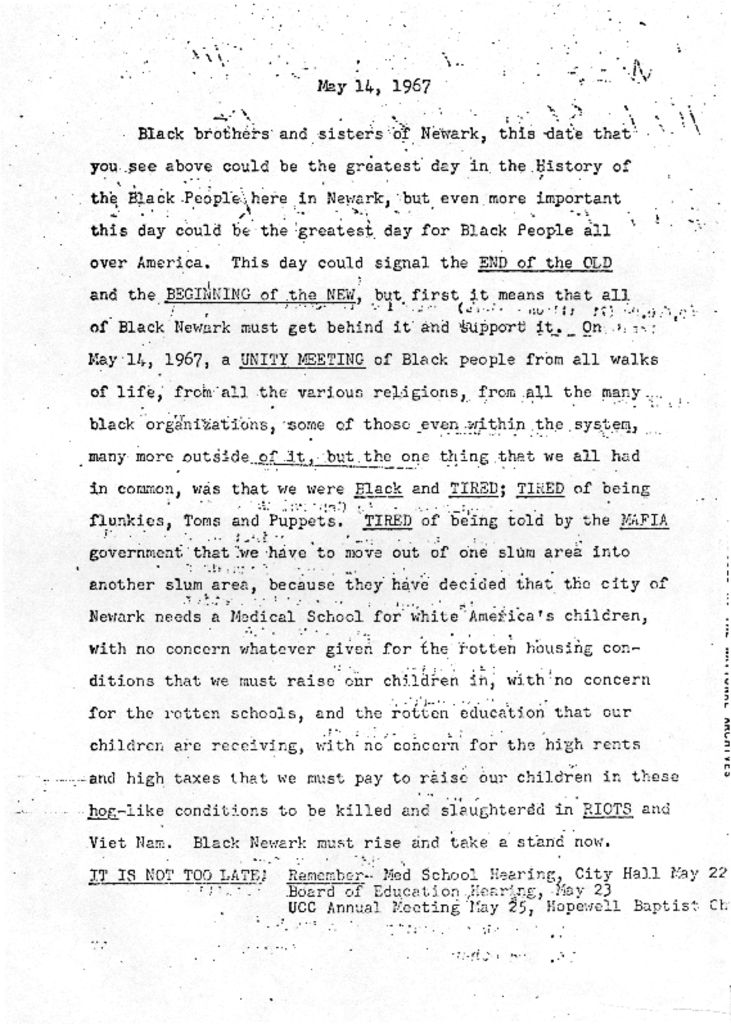

Flyer distributed in the Central Ward to encourage community members to attend a Unity Meeting on May 14, 1967 to protest the seizure of land for the construction of a medical school. — Junius Williams Collection

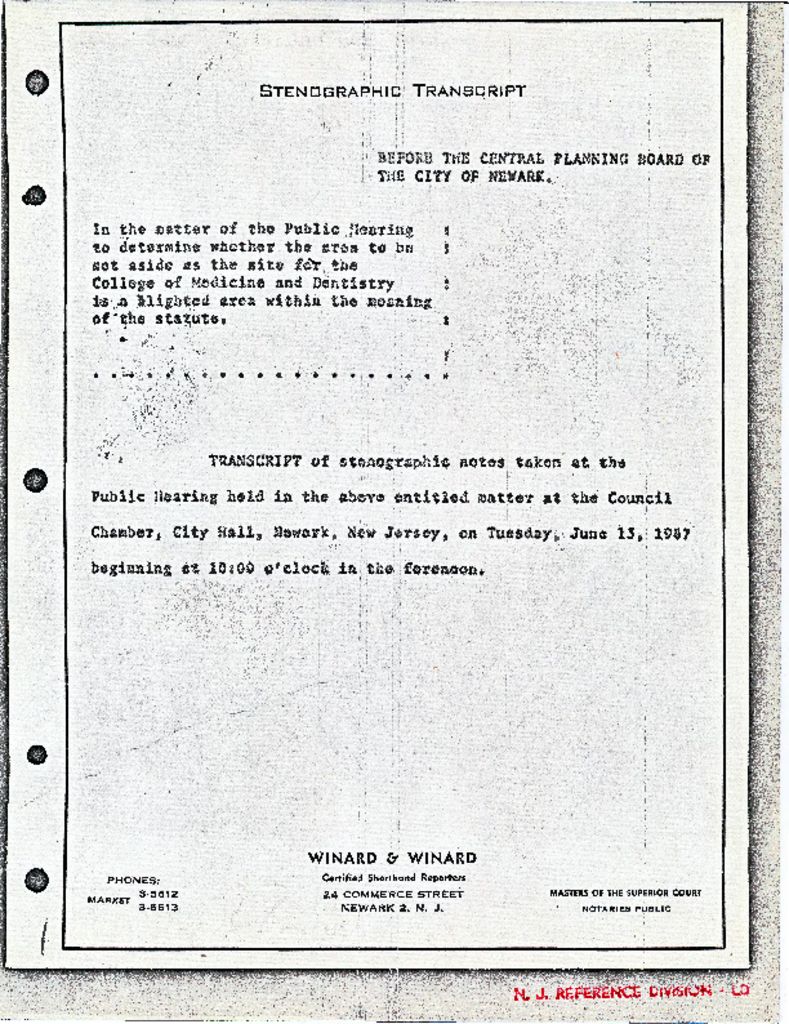

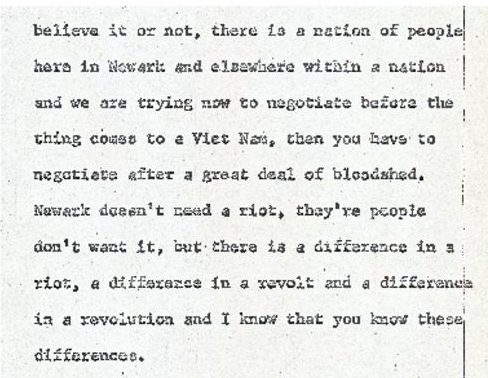

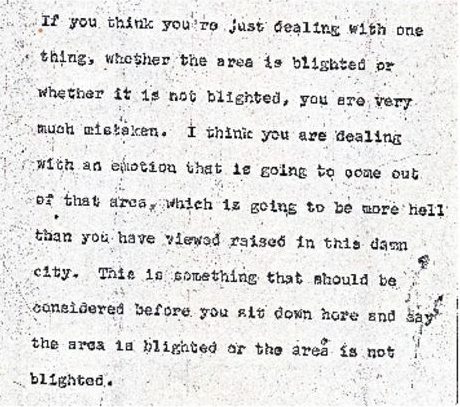

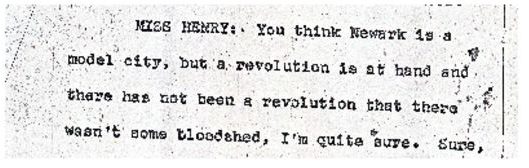

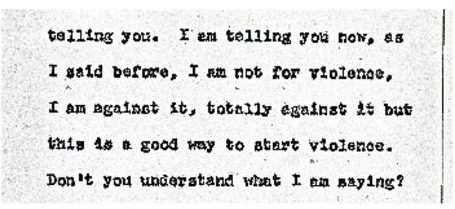

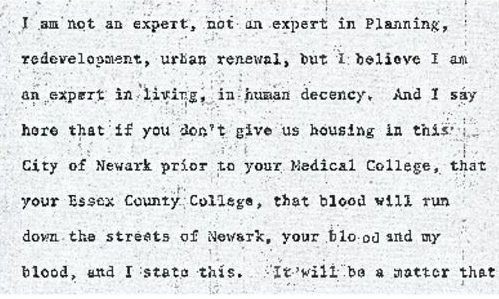

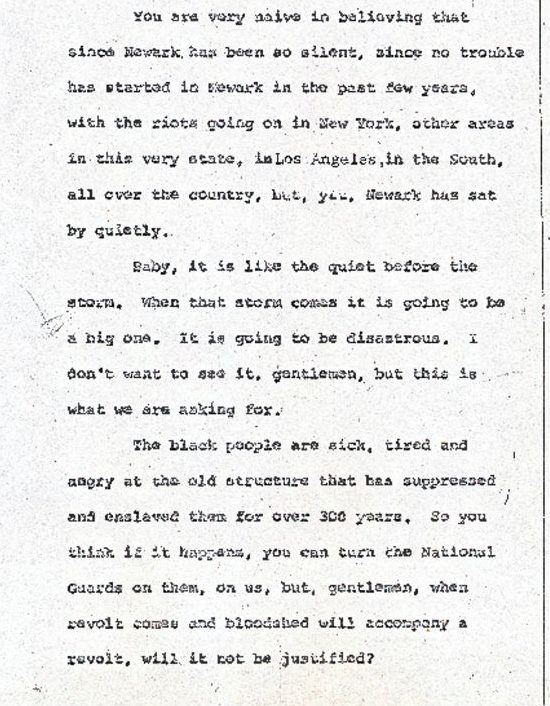

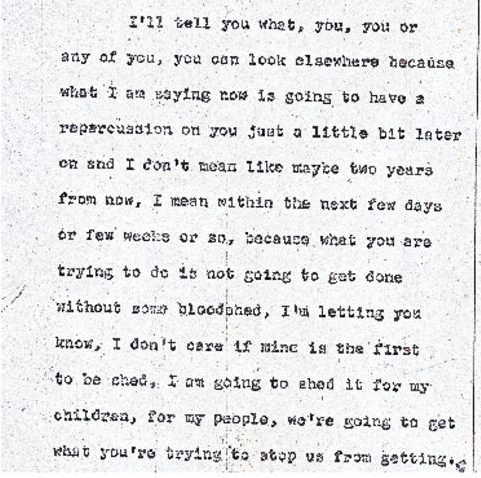

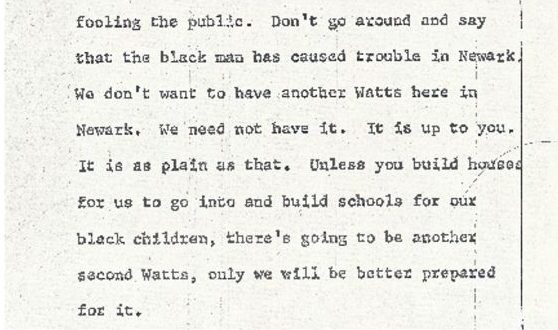

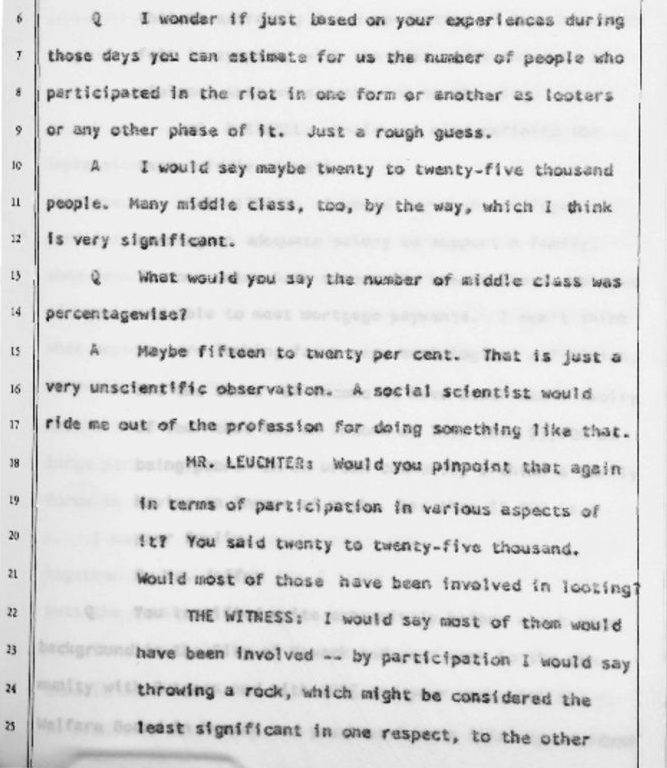

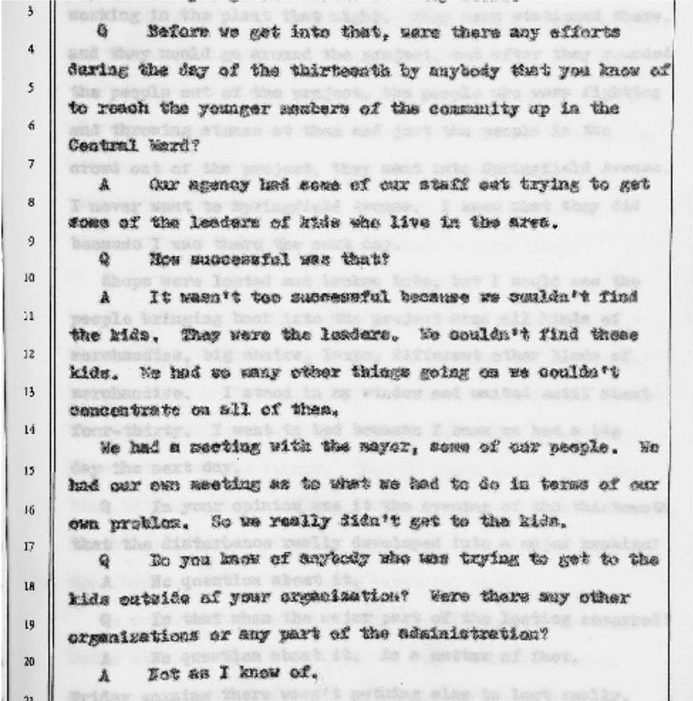

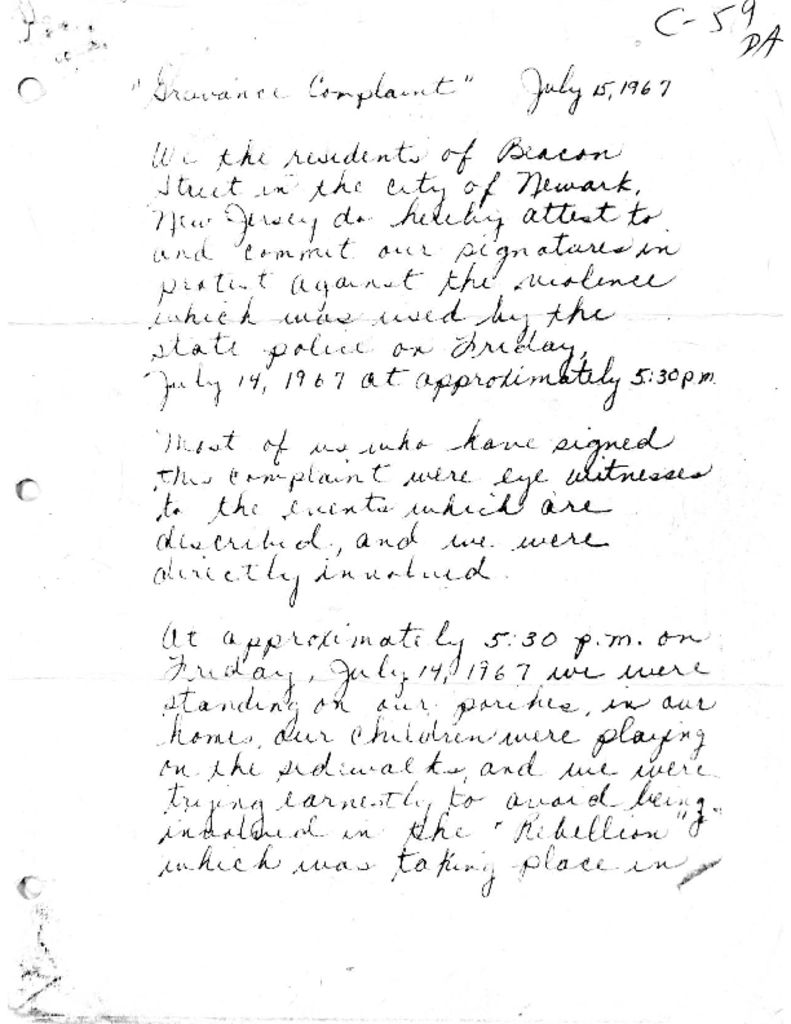

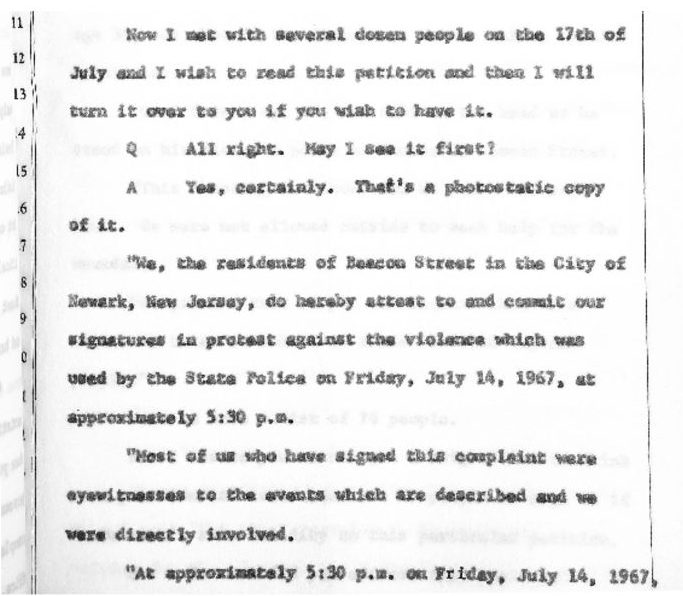

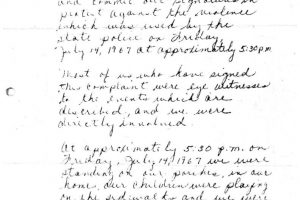

Excerpts from the stenographic transcript of various Newark residents’ comments to the Central Planning Board in June 1967 during the infamous “blight hearings.” These public hearings were held to determine if areas in the Central Ward were “blighted” so that the lands could be taken by eminent domain for the construction of the New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry. These excerpts were selected from over 500 pages of transcripts to illustrate the high tensions and predictions of impending violence in Newark just weeks before the 1967 rebellion. — Credit: Newark Public Library