Outcomes and Impacts

The events that unfolded during the 1967 Newark rebellion had deep, lasting impacts upon the city’s political, economic, and social structures. Although city residents came away from the rebellion with varying interpretations and understandings of what exactly happened, there was little disagreement that Newark had undergone a serious transformation from the events of July 13-18. As Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) member Eric Mann wrote in August 1967, “In the wake of the rebellion has come a shake-up of the political equilibrium of the city. The right has moved to the right. The Negro center- middle class Negroes with no real program except that black men replace white men in government positions- has increased its militancy. The white center- the mayor’s coalition of Negroes and Italians- is crumbling. The most encouraging development is that the black left is moving to the left.”

————

The Negro center- middle class

Negroes with no real program except that black men replace white men in

government positions- has increased its militancy.

————

One of the most visible signs of this “shake-up of the political equilibrium” was the National Conference on Black Power, held at the Episcopal Cathedral House on 24 Rector Street. As the remaining National Guard and State Police presence vacated the city, civil rights and Black Power activists, politicians, and artists arrived in Newark for the so-called “Black Power Conference.” Prominent figures, including Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Chairman H. Rap Brown; Cambridge, Maryland Nonviolent Action Committee leader Gloria Richardson; Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) Director Floyd McKissick; Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) leader Jesse Jackson; US Organization founder Ron Karenga; artist Romare Bearden, and many others were present to “explore the issue of power as it relates to specific problem areas in the life of black Americans.” According to reporter L.H. Stanton, “All seemed to understand one thing—that people who some in America persecute solely because they are black, must unite under that banner of blackness and fight the adversary with a common front…even though that struggle may be with variant tactics…”

While this diverse array of Black leaders met to discuss the creative possibilities of “Black Power,” Newark’s white communities tried to make sense of the rebellion and how to move forward. Some white Newarkers decided to flee to the suburbs, bringing their tax base with them. Others, such as North Ward resident Anthony Imperiale, decided to take a more confrontational approach to restore “law and order” in Newark. According to NCUP member Junius Williams, “Imperiale and his men endeared themselves to the white ethnic communities most notably in the North and West wards, the last remaining strongholds of the remaining Italian and Irish populations, by ‘standing guard’ at the perimeters of white neighborhoods during the Rebellion. He vowed, ‘If the Black Panther comes, the White Hunter will be waiting.” In the weeks and months following the rebellion, Imperiale led the reactionary charge to curb the political momentum that the rebellion represented for Black political empowerment in the city.

————

Some white Newarkers decided to

flee to the suburbs, bringing their tax base with them.

————

This political momentum gained by Newark’s Black communities after the rebellion was clear in the ongoing struggle to prevent the construction of a medical school on a 150-acre plot that would displace 20,000 Central Ward residents. In the months, weeks, and days before the rebellion, it was evident that the city was prepared to go ahead with the construction, in spite of vocal organized resistance by these residents. After the rebellion, however, the balance of the political scales shifted. According to Louise Epperson, a leader of the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal, “I tried for weeks, days…months to get in touch with Dr. Cadmus, who was President of the College of Medicine and Dentistry at that time. I could never get any further than his secretary, never would let me speak with him. But after the riots, everybody wanted to talk to me.” Realizing their increased political power after the rebellion, Newark’s Black communities sought to organize in the following years to address the many issues plaguing their city and ultimately, elect Newark’s first Black mayor.

References:

Eric Mann, “The Newark Community School,” Liberation Magazine, August 1967.

L.H. Stanton, “The Black Power Conference- A View from Inside,” July 27, 1967.

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power.

Clip from interview with NCUP member Carol Glassman, in which she describes the racial tensions after the 1967 Newark rebellion. Glassman describes the mindset and actions of some in Newark’s white population, who felt that their communities were under attack during and after the rebellion. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from “Newark: The Slow Road Back,” which contains footage from the National Conference on Black Power, held in Newark from July 20-23, 1967. The conference was held just days after the 1967 Newark rebellion and attracted dozens of national figures to the city, such as H. Rap Brown, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The clip also shows news footage from an interview with Governor Richard Hughes, in which he says that Black Power “undoubtedly” contributed to the 1967 Newark rebellion. — Credit: Sandra King

Clip from an interview with North Ward vigilante and politician Anthony Imperiale, in which he describes the ways that he responded to Black militants in Newark in the 1960s. Imperiale and his North Ward Citizens Committee gained notoreity for the cache of weapons, including an armored car, that they claimed to have and for giving voice to white fears and resentment after the 1967 Newark rebellion. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from interview with UCC member Edna Thomas, in which she describes the sense of empowerment she felt in her community after the 1967 Newark rebellion. Many Black residents of Newark saw the rebellions as “empowering” because of the collective, though unorganized, effort to challenge the power structures in the city that had shut them out for decades. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Explore The Archives

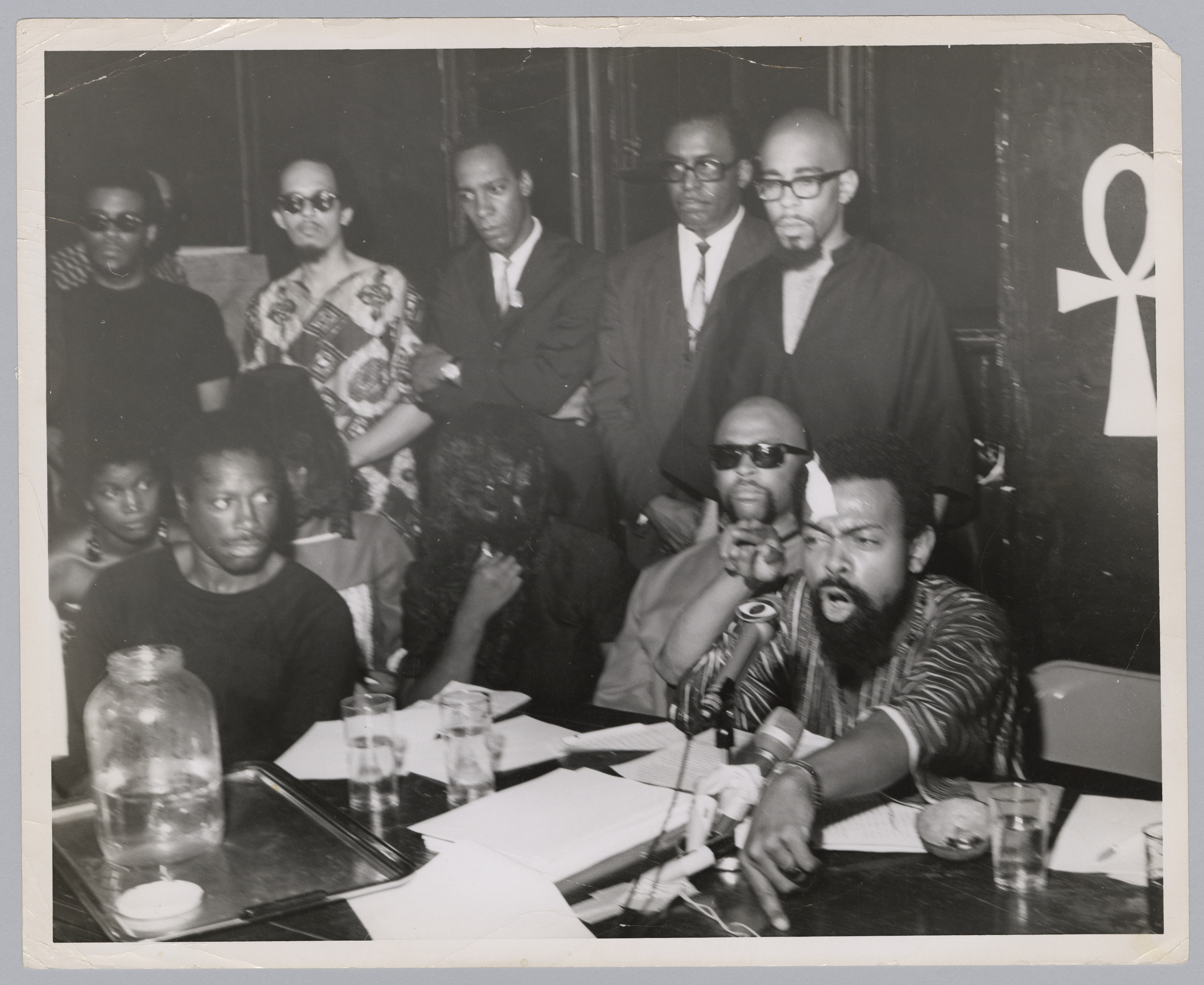

A bandaged Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) holds a press conference inside the Spirit House in Newark during the National Conference on Black Power. Baraka was wounded after being arrested on gun charges and beaten by Newark Police during the 1967 rebellion. To the left of Baraka are cultural nationalist leader Ron Karenga (US Organization) and the mother of James Rutledge (veiled), who was shot 39 times by State Police during the rebellion. — Credit: Amiri Baraka Papers, Columbia University Library

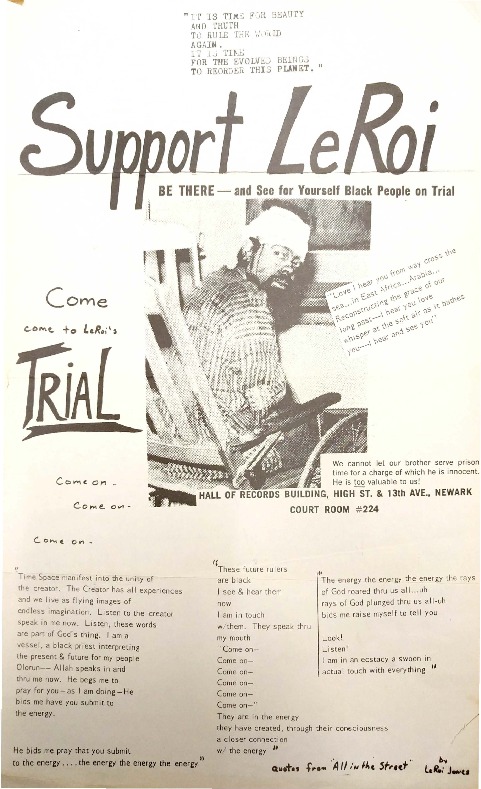

Flyer distributed to encourage community support at the trial of LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), who was arrested and beaten by Newark police during the 1967 Newark rebellion for alleged gun possesion. The flyer shows a picture of Jones bloodied and bandaged after his arrest. — Credit: Amiri Baraka Papers, Columbia University Library

Clip from “Newark: The Slow Road Back,” in which former North Ward Democratic Party Chairman Steve Adubato describes the mindset of the white community in the North Ward during the 1967 Newark rebellion. Adubato recalls, “We had to rethink who we were. Are we in a war? If we get out into surburbia guess what? It’s over, there’s no war, no fighting, no racism, no problem, no Blacks, no Baraka’s- none of that.” Adubato came into political power following the rebellions as a more “moderate” white politician, in comparison to fellow Italian-American Anthony Imperiale, a vigilante who became the figurehead of white backlash in the late 1960s. — Credit: Sandra King

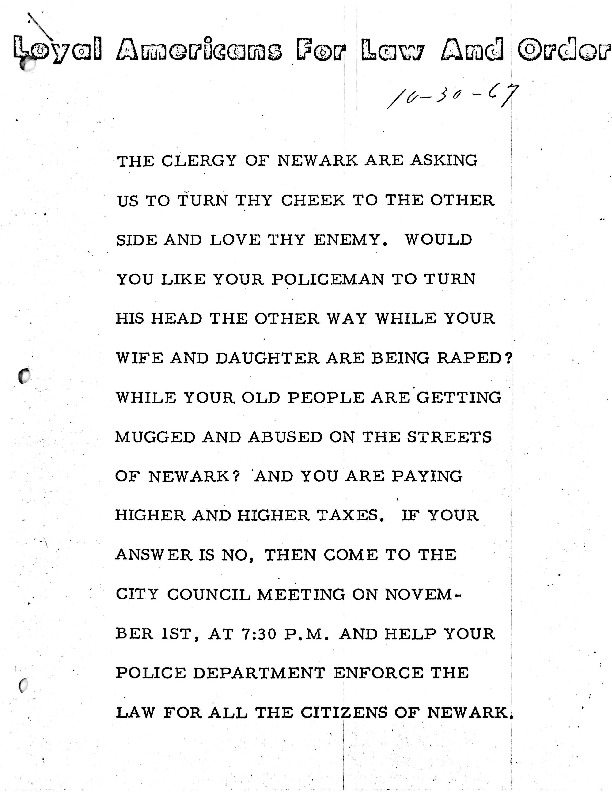

Flyer distributed by the organization Loyal Americans for Law and Order (LALO), calling for residents to attend a City Council meeting on November 1, 1967 “and help your police department enforce the law for all the citizens of Newark.” LALO was formed immediately after the 1967 Newark rebellion in response to what the organization saw as “Godless…philosophies subverting the negro communities where is found waste, ignorance and lawlessness.” — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

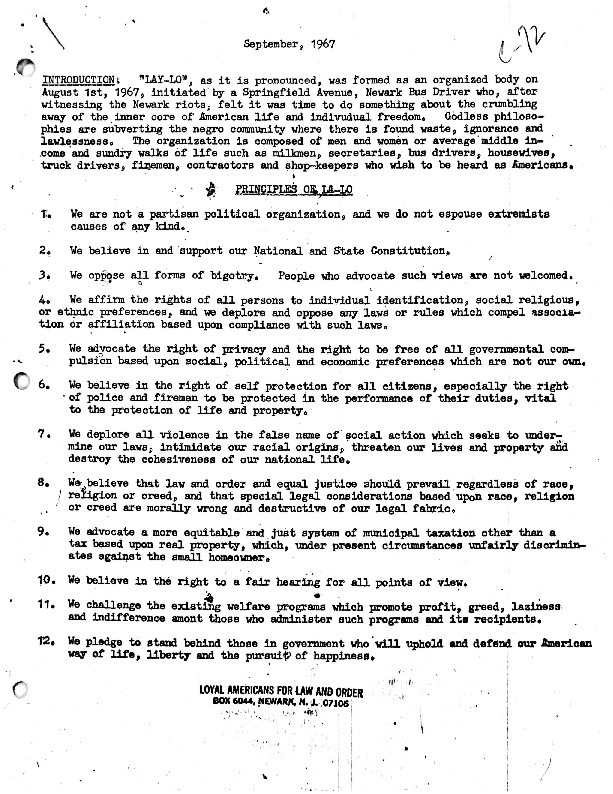

Leaflet distributed by the organization Loyal Americans for Law and Order (LALO), introducting the organization’s mission and statement of principles. LALO was formed immediately after the 1967 Newark rebellion in response to what the organization saw as “Godless…philosophies subverting the negro communities where is found waste, ignorance and lawlessness.” LALO and other white reactionary organizations utilized stereotypes of African-American criminality, laziness, and ignorance to promote a “law and order” response to growing Black political advancement in the city after the rebellion. — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

Clip from an interview with United Community Corporation (UCC) member HIlda Hidalgo, in which she describes the decline of population and business in Newark after the 1967 rebellion. Many believe that the rebellions expedited a process of suburbanization that had begun long before their outbreak in 1967, crippling the city’s tax base. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from an interview with community leader Louise Epperson, in which she describes how the Medical School Fight changed after the 1967 Newark rebellion. Mrs. Epperson explains how she had a difficult time contacting any officials involved in the Medical School plans before the rebellion and how that changed afterwards. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries