The Police

“People complain, talk about State Police force and Gestapo methods and things of that nature, and, as I said before, you can’t stop a rioting by glancing at people.” -Arthur Sills, Attorney General of New Jersey

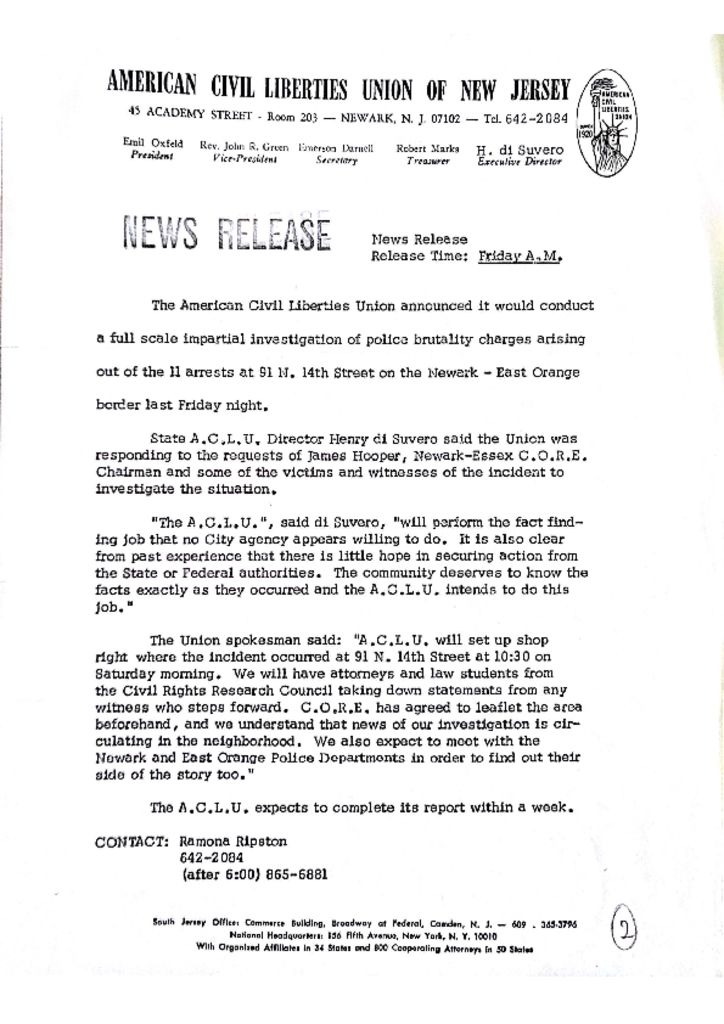

On July 12, 1967, African American taxi driver John Smith was arrested and beaten by police after being pulled over near the Fourth Precinct on 17th Avenue. As crowds gathered outside the precinct that night to protest, a woman cried out, “We don’t just want to talk about John Smith—we want to talk about what we see here happening every day, time and time again.” Just days earlier, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had announced a “full scale…investigation of police brutality charges” stemming from the violent arrests of eleven Black Muslims on the Newark-East Orange border on July 7th. After years of unsuccessful struggles to reform police practices, the close proximity of these two incidents brought police-community tensions to a head outside the Fourth Precinct on July 12th.

Just before midnight, as Timothy Still of the United Community Corporation (UCC) was addressing the crowd, a Molotov cocktail, thrown from a rooftop across the street, hit the side of the precinct. Still and CORE leader Robert Curvin negotiated with Inspector Melchior for 15 minutes to calm the crowd without a police presence. As Still, Curvin, and others attempted to calm and redirect the energy of the crowd, policemen emerged from the precinct and were met with rocks and bottles. At this point, “police rushed out of the precinct in full riot gear,” pursuing the now fleeing crowd with nightsticks. After witnessing police actions that night, Newark Human Rights Commission chairman Albert Black testified, “I can understand the position of the police of being frightened and…being like sitting ducks…but I saw no reason why they should use…such language as ‘black bastards’ and ‘black S.O.B’s…So I had to come to the conclusion that the ugly head of racism has certainly protruded itself into the picture.” The fear and uncertainty of Newark police officers that night can certainly be understood in the face of flying rocks, bottles, and Molotov cocktails. The accounts of officers arresting people on their way home from work and beating them inside the precinct, however, are more difficult to justify. According to Black, “the precinct could be defined as a slaughter house. You were actually walking through pools of blood.”

The next night, conflict resumed outside the Fourth Precinct as Newark Police clashed with demonstrators who gathered to picket and protest police brutality. Having learned of a planned demonstration organized by the UCC and Newark Community Union Project (NCUP), Deputy Chief John Redden ordered police on the scene “not to wear helmets and not to carry nightsticks.” Around 7:30, Newark Human Rights Commission Executive Director James Threatt announced to a crowd of 300 that a Black police officer was being promoted to the rank of captain. Seeing this as a token gesture, some in the crowd hurled rocks and bottles toward the precinct. In response, police were sent out with helmets and nightsticks to disperse and pursue the crowd.

While police clashed with protestors outside the Fourth Precinct, disturbances spread to surrounding streets and neighborhoods in the form of “vandalism” and “looting,” as a disorganized Newark Police Department struggled to contain the sprawl. After several hours of conversations and debate between city officials, a “hysterical” Mayor Addonizio phoned Governor Richard Hughes around 2:30 AM to request the deployment of State Police and the National Guard to restore order to the city. While these conversations were taking place, Newark police fatally shot 45-year-old Rose Abraham while they were “attempting to clear the area of looters.” Two more would be shot to death by sunrise.

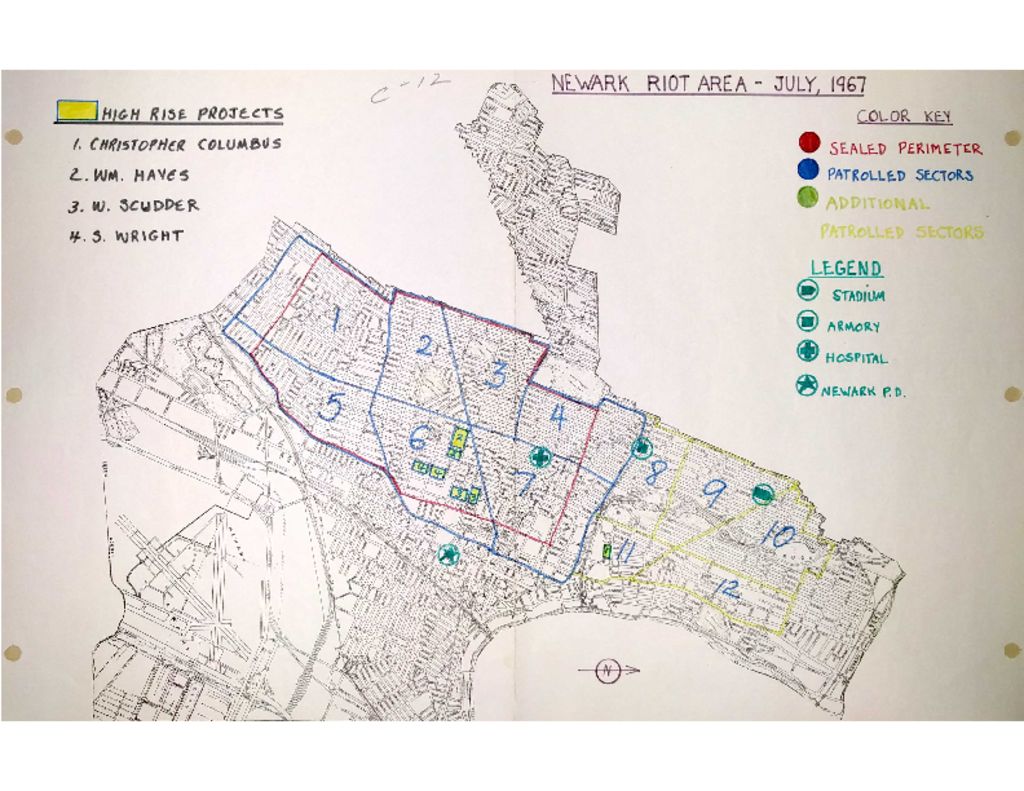

When the State Police and National Guard arrived in Newark early Friday morning, a chain of command was established with Colonel David Kelly of the NJ State Police as the commanding officer over the State Police (475 troopers) and National Guard (4,000 men). Newark Police Director Dominick Spina was to retain control over the city police (1,300 officers). Therefore, control of the situation in the city of Newark was effectively turned over to individuals who were unfamiliar with the city, its landscape, and its people.

After touring the “riot area” with Kelly, Spina, Addonizio, and General Cantwell of the National Guard, Governor Hughes issued a proclamation declaring the city of Newark to be in a state of emergency. This proclamation established a curfew, restricted traffic, prohibited the sale and possession of firearms and alcohol, and authorized law enforcement to “take any and all measures requisite to quell disturbances and outbreaks of violence.”

As National Guardsmen established blockades throughout the “riot area,” looting subsided over the course of the day Friday. However, as looting diminished, “weapons fire” became more intense and reports of sniper fire quickly escalated. Although the list of sniper reports was extensive, most Black residents refuted the presence of civilian snipers. Many believed that the reported sniper fire was actually crossfire from other law enforcement, resulting from a flawed communication system with each agency being on a different radio frequency. Despite a LIFE magazine photograph depicting an alleged “sniper,” (which many believe to have been staged), no snipers were ever found. Whatever the case may be, law enforcement responded to “sniper fire” by shooting indiscriminately into high-rise apartments, which they believed to be sniper perches. By the end of the day, 906 were arrested, 10 more were dead (including 10-year-old Eddie Moss), and the “riot” was largely under control.

Although sporadic looting remained throughout the weekend, the rebellion took on a different character by mid-day Saturday. To many in the Black community, there were two different “riots” that took place. According to Robert Curvin, “the rebellion on the part of the community was essentially over and…now we were in a period of retaliation by the police forces that were sent into the city to restore order but were in fact continuing the disorder by their shooting and their attacks on the community.”

Recognizing the shift in the dynamics of the rebellion, community leaders spent much of Sunday attempting to convince city and state officials to withdraw the state police and National Guard. After much deliberation, Governor Hughes finally announced early Monday morning that the majority of the occupying troops would pull out of the city.

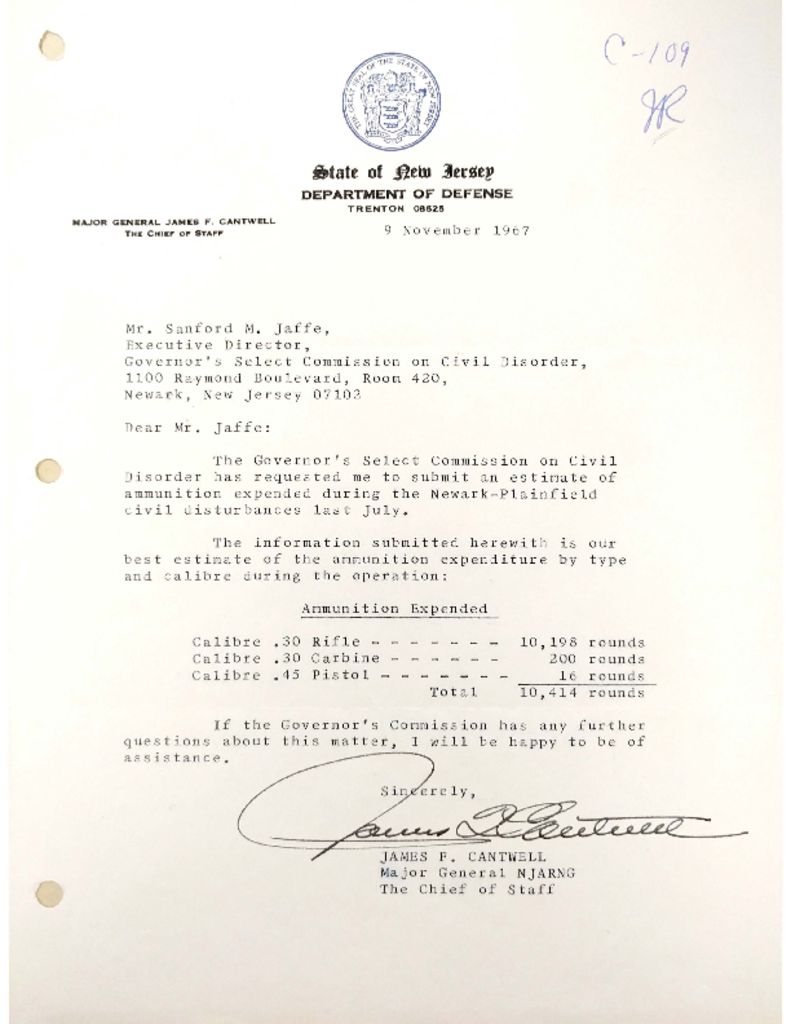

Over the course of five days, there were: over 13,000 rounds of ammunition expended by State Police and National Guardsmen (no record was kept by Newark Police); 1,000 civilians injured; 1,500 civilians arrested; 23 victims of homicide; and “no cause for indictment” of any police officer or National Guardsmen.

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Ron Porambo, No Cause for Indictment: An Autopsy of Newark

Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action

Tom Hayden, Rebellion in Newark: Official Violence and Ghetto Response

Witness Testimonies Before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder

Video clip from the documentary “Newark: The Slow Road Back,” in which Junius Williams describes the actions of police as “rioting” and the resultant shooting of Eloise Spellman on July 15, 1967. — Credit: Sandra King

Clip from interview with UCC member James Walker, in which he describes the actions of Newark police, state police, and National Guardsmen during the 1967 rebellion. Walker discusses police and National Guard engaging in “looting,” as well as indiscriminately shooting nonviolent offenders. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Letter submitted to the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders by Major General James Cantwell of the New Jersey National Guard regarding the amount of ammunition fired by the National Guard during the 1967 rebellions in Newark and nearby Plainfield. The report includes the types and amounts of ammunition used by National Guardsmen, estimated to total over 10,000 rounds. — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

Clip from interview with poet and activist Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), in which he describes being beaten by Newark Police officers the night of July 13, 1967. Jones was arrested on gun charges after driving through the Central Ward in his Volkswagen Bus, bringing injured people to the hospital. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

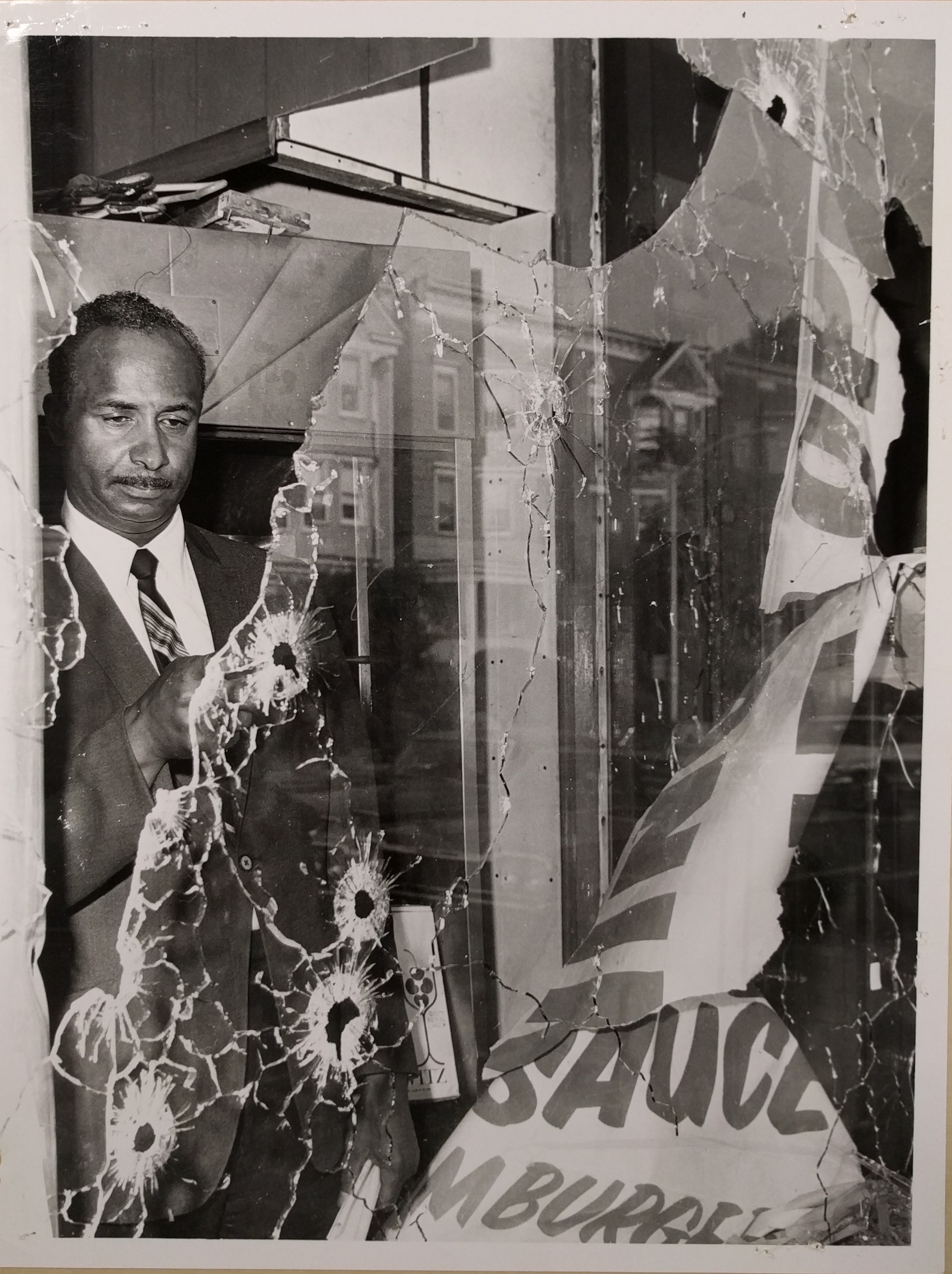

Photo submitted by Earl Harris to the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders to demonstrate the damage done to his business at 124 Elizabeth Avenue by State Police and Newark Police. According to Harris, “they shot up a business that I had invested every pennt in that I could possibly get my hands on, my business was two weeks away from opening and it was shot up.” — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

Explore The Archives

Press release from the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey announcing an investigation into “police brutality charges” stemming from the violent arrests at a Black Muslim house on the Newark-East Orange border on July 7, 1967. The close proximity of this incident to John Smith’s arrest and beating on July 12th brought police-community tensions to a head and “sparked” the 1967 Newark rebellion. — Credit: Newark Public Library

New Jersey State Police map of the “Newark Riot Area- July, 1967” depicting police perimeters, patrols, landmarks, and “high rise projects.” — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

Clip from the documentary “Newark: The Slow Road Back,” in which Sally Carroll, a former President of the Newark NAACP, describes police and National Guardsmen shooting into high-rise apartment buildings, which resulted in the death of Eloise Spellman. — Credit: Sandra King

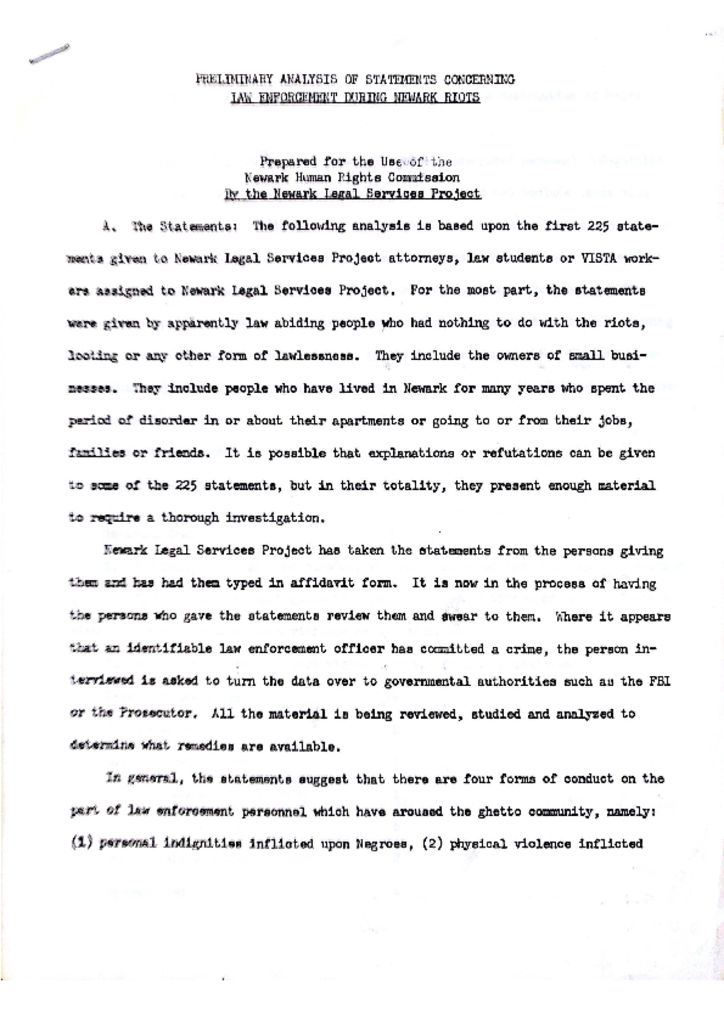

Statement prepared by Newark Legal Services Project for the Newark Human Rights Commission regarding the first 225 statements given to NLSP about law enforcement actions during the 1967 Newark rebellion. The actions of law enforcement officers are summarized in four categories: “personal indignities inflicted upon Negroes,” “physical violence inflicted upon Negroes,” “indiscriminate shooting,” and “deliberate destruction of Negro property.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

Clip from interview with Black Power advocate Dr. Nathan Wright, in which he describes confronting a police officer who had aimed his rifle at a group of people. Dr. Wright remembers citing a City Hall ordinance which restricted the use of firearms by police to include only instances of self-defense. This changed with Governor Hughes’ State of Emergency proclamation, which ordered law enforcement to take “any and all measures requisite to quell disturbances and outbreaks of violence.” — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

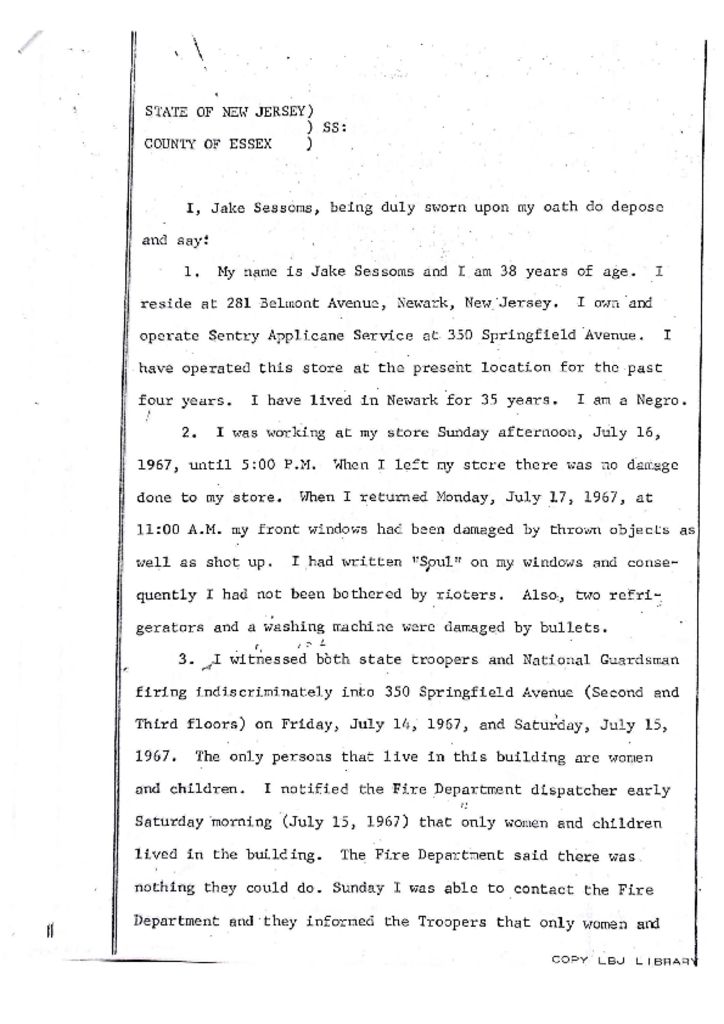

Deposition of Jake Sessoms, African American owner of Sentry Appliance Service on Springfield Avenue, before the State of New Jersey Grand Jury. Sessoms stated “I had written ‘Soul’ on his windows and consequently I had not been bothered by rioters.” However, Sessoms noted that his front windows were damaged by thrown objects and gunfire the night of Sunday July 16, 1967. — Credit: Newark Public Library