The Community

On the evening of July 12, 1967, residents of the Hayes Homes Projects watched as John Smith was dragged inside the Fourth Precinct directly across the street. As the crowd grew in size and anger, it quickly became clear that John Smith’s arrest wasn’t the only issue on the minds of the people. One woman outside of the precinct shouted “We want to talk about what we see here happening every day!” What the people saw was a city government that refused to adequately address issues plaguing their communities, such as police brutality, job discrimination, and urban renewal. With little meaningful access to the formal political system in the city to change these conditions, the people took politics to the streets that week in July.

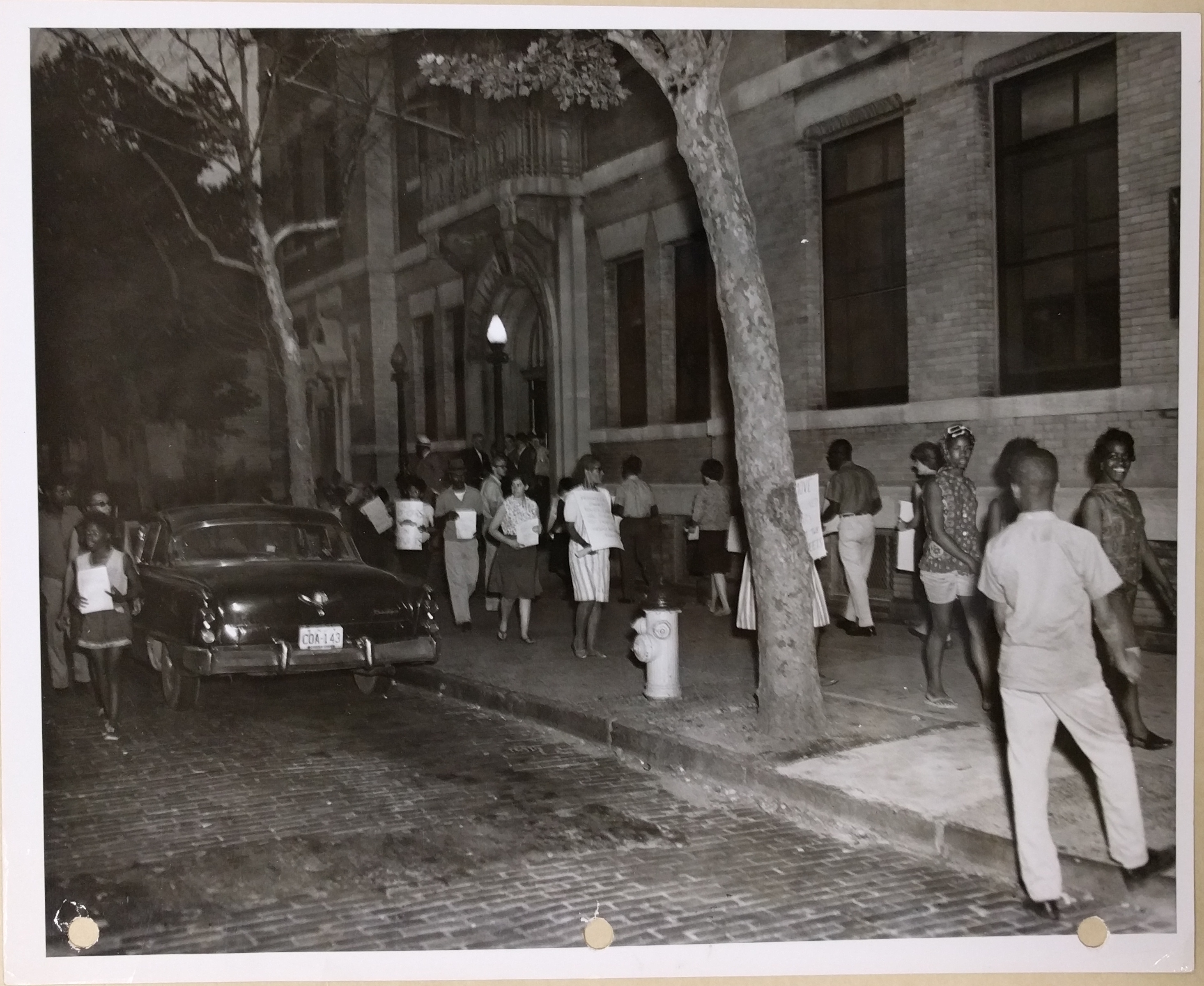

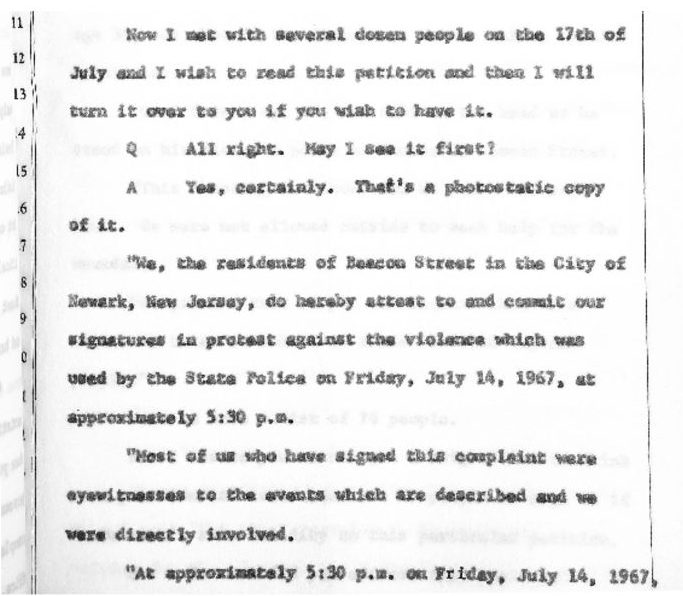

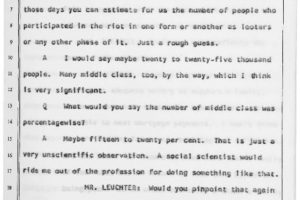

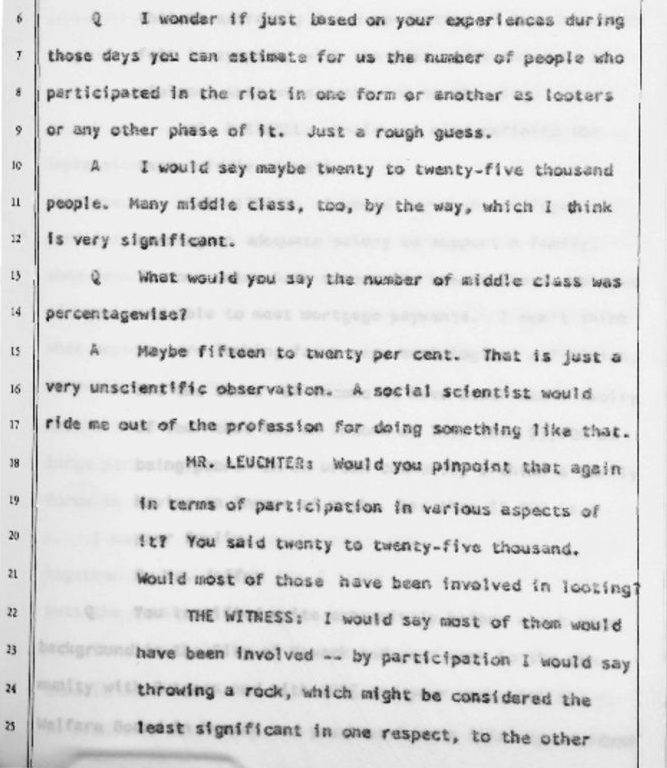

Veteran community organizer Robert Curvin estimated that around 25,000 people in Newark participated in the 1967 rebellion in some way, shape, or form. This participation, Curvin said, ranged from “throwing a rock” to “trying to hurt somebody.” Beyond rock-throwing and acts of violence, though, community members took action in many ways during the rebellion to address the problems taking place in their neighborhoods. People marched on picket lines to protest police brutality, submitted petitions to government agencies, and took to the streets to try to promote peaceful demonstrations. Though the range of actions taken by individuals in the community varied, “an extremely large percentage of the community felt in sympathy with the riot.”

Many commonly told stories of the 1967 Newark rebellions focus on acts of “looting” stores and businesses by community members. While it is true that “looting” was widespread during the rebellion, much of this activity was directed at white-owned businesses that were known to exploit African-American communities in Newark. According to Don Wendell of the United Community Corporation, “The wrath of the people was taken out on the store owners whom they felt were robbing them.” As Tom Hayden of the Newark Community Union Project put it, “The people voted with their feet…They were tearing up the stores with the trick contracts and installment plans, the second-hand television sets going for top quality prices, the phony scales, the inferior meats and vegetables.” Businesses that had a reputation for treating African-American customers fairly were generally left alone.

Speaking about the actions of Newark’s Black communities during the rebellion, former Essex County Republican Freeholder Earl Harris told the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders: “Negroes have been painted because of these disturbances as people who are irresponsible, going around throwing bricks, filling up a bottle of gas, throwing it like a God-damned fool, but it is not like that. The true picture must be told. The truth of the matter is there are conditions that cause that person who is irresponsible enought to throw that rock to get it and throw it.”

References:

Witness Testimonies from the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders

Tom Hayden, Rebellion in Newark: Official Violence and Ghetto Response

Clip from “Newark: The Slow Road Back,” in which Bill Payne describes his experiences during the 1967 Newark rebellion. Payne recalls participating in “Operation Arm Band,” an effort to enlist community leaders to promote peace in the city, and why he decided to take the arm band off. — Credit: Sandra King

Leaflet announcing a mass rally outside of the Fourth Precinct on July 13, 1967 to protest police brutality. The leaflets, printed by the United Community Corporation’s (UCC) Area Board 2 and distributed by the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP), were made in response to the arrest and beating of John Smith outside the Fourth Precinct the previous night. — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

Explore The Archives

Witness testimony of Robert Curvin before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder on October 17, 1967. Curvin states that “an extremely large percentage of the community felt in sympathy with the riot, with the acts of violence that were occurring in the city.” — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository

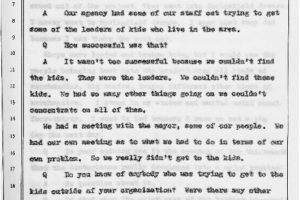

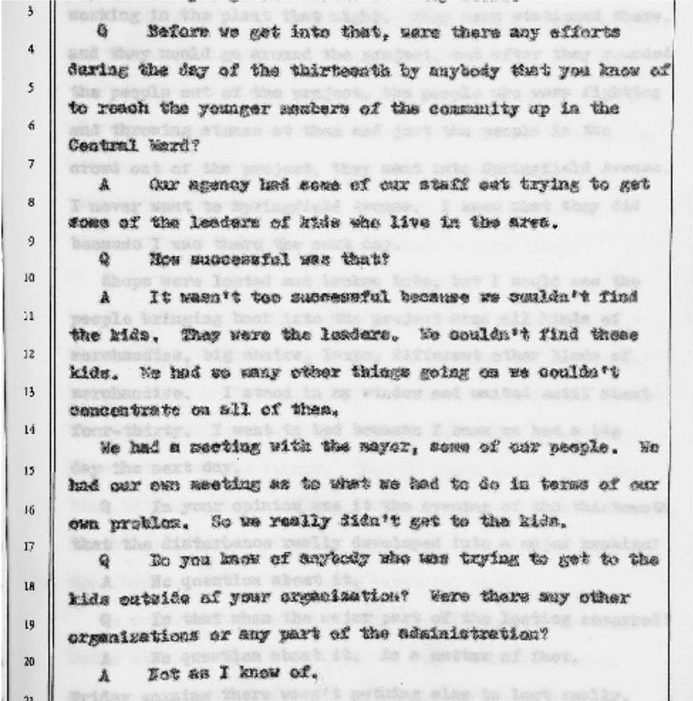

Witness Testimony from Timothy Still, President of the UCC, before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders hearings. Still describes the relationship between “kids” in Newark and community leaders and organizations during the 1967 Newark rebellion. According to Still, “we couldn’t find the kids. They were the leaders.” — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository

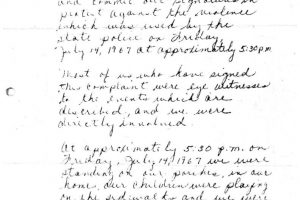

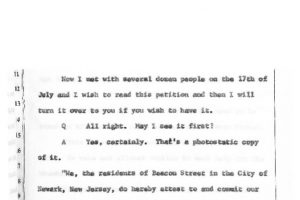

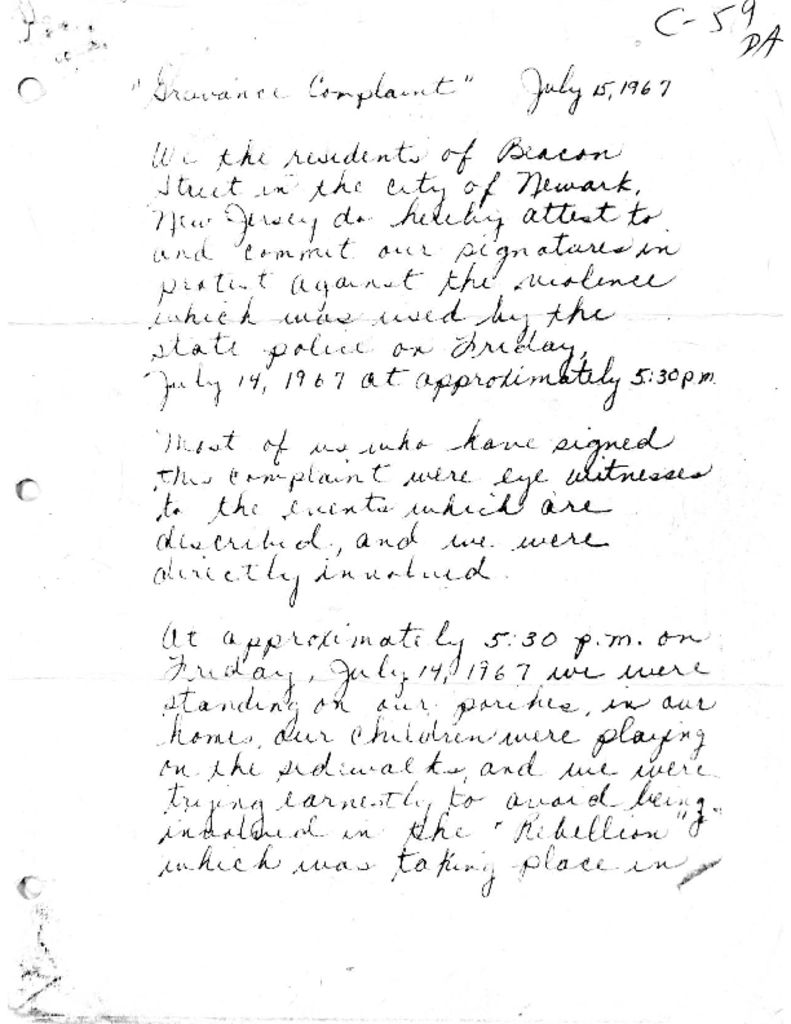

“Grievance Complaint” compiled by Albert Black, Chairman of the Newark Human Rights Commission, and residents of Beacon Street on July 15, 1967 against police violence during the 1967 Newark rebellion. The complaint describes the shooting and wounding of Karl Green and James Snead by State Police on July 14th on Beacon Street. According to the petitioners, “without warning or provication, the state police began firing upon us.” The petition was submitted to the Newark Human Rights Commission, FBI, State Police, Newark Legal Services Project, and other investigation committees. — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

Clip from interview with Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) member Carol Glassman, in which she describes her experiences during the 1967 Newark rebellion. Glassman explains that there was a “party atmosphere” for some involved in “looting” during the first two nights, but also a great deal of frustration being expressed. This atmosphere changed drastically upon the arrival of the State Police and National Guard on Friday, July 14th. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Community Leaders

After the arrest and beating of John Smith on July 12, 1967, community leaders and organizations, such as the UCC, CORE, and Newark Legal Services Project, mobilized quickly to coordinate the anger and demands for justice raised by the people. As influential as these leaders and organizations may have been before the rebellion, it became clear that the people “were going to do what they obviously wanted to do.” According to Timothy Still, President of the United Community Corporation, “Our agency had some of our staff out trying to get some of the leaders of kids who live in the area. It wasn’t too successful because we couldn’t find the kids. They were the leaders.”

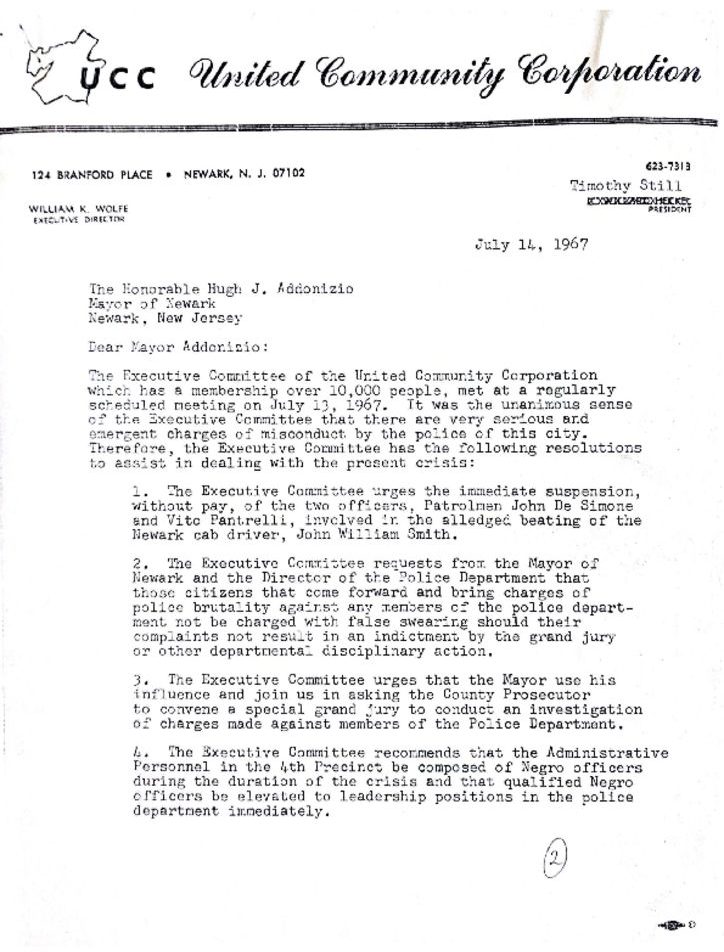

Though community leaders may not have represented the interests of the entirety of Newark’s African American communities during the 1967 rebellion, they played many important roles. One of these roles was acting as intermediaries between the people and the government. As Earl Harris stated, “We wanted to talk to [Mayor Addonizio] … because we felt in our hearts that we had dialogue with the guy who was going to throw that Molotov cocktail or that brick.” The day after Smith’s beating, the UCC met to write a letter to Mayor Addonizio proposing a course of action to address the impending crisis, which was rooted in longstanding issues of police-community relations in Newark. Additionally, community leaders including Earl Harris, Jimmy Hooper (CORE), Harry Wheeler, George Richardson, Eulis “Honey” Ward, Robert Curvin, and Tom Hayden (NCUP), met continuously with Mayor Addonizio, Governor Hughes, and others on behalf of Newark’s Black communities.

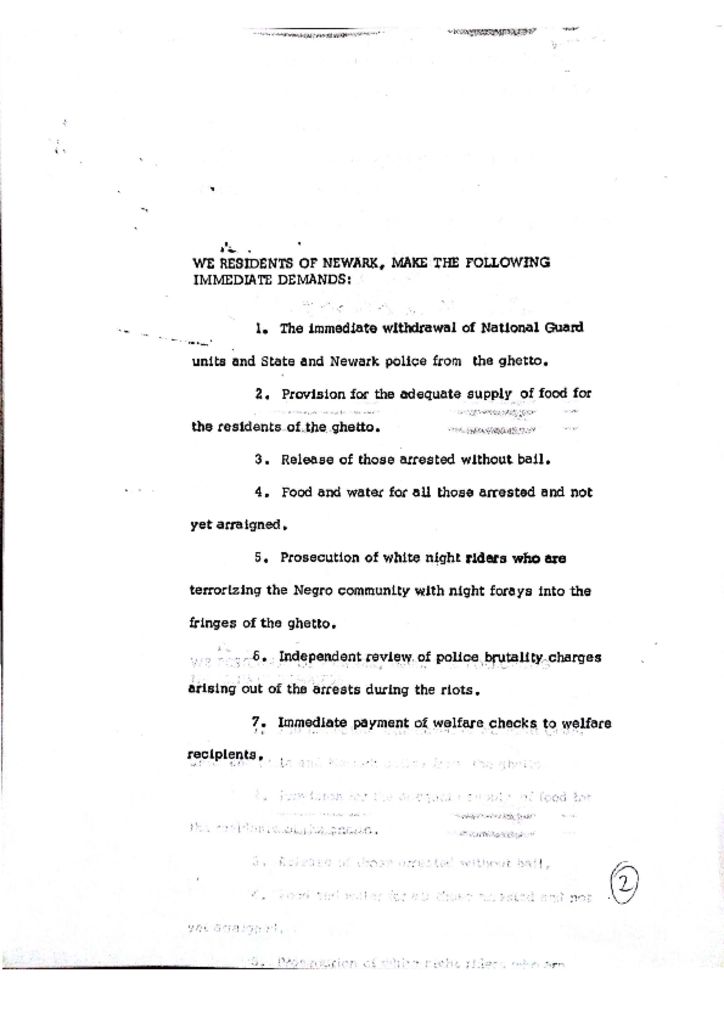

Community leaders used this access to government officials to demand action upon the variety of problems plaguing the city. To address the immediate needs of the community related to the rebellion, leaders sought access to food and medicine for people affected by the rebellion, removal of State Police and National Guard, and justice for victims of police violence. These community leaders, however, wanted more from government officials than merely responding to the crisis of the rebellion. Many community leaders wanted to capture the momentum of the rebellion to change the conditions in Newark that caused the rebellion in the first place. At a press conference held by members of several civil rights organizations on July 16th, Jesse Allen (UCC), Jimmy Hooper (CORE), Donald Tucker (CORE), Marion Kidd (People’s Action Group), and Phil Hutchings (SNCC) presented a list of immediate and long range demands upon city, state, and federal officials. These demands reflected issues that had long been resisted by city officials and would come to represent a new stage in the struggle for civil rights and Black Power in Newark.

References:

Witness Testimonies from the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders

Clip from interview with UCC member James Walker, in which he describes a meeting between community leaders and Mayor Addonizio on July 13, 1967, the day after John Smith was arrested and beaten outside the Fourth Precinct. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Letter from Timothy Still, President of the UCC, to Mayor Addonizio on July 14, 1967. Members of the UCC’s Executive Committee met on July 13, 1967 to create a list of recommendations for the City Government to address the violence outside the Fourth Precinct the previous night in response to the beating of John Smith. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Explore The Archives

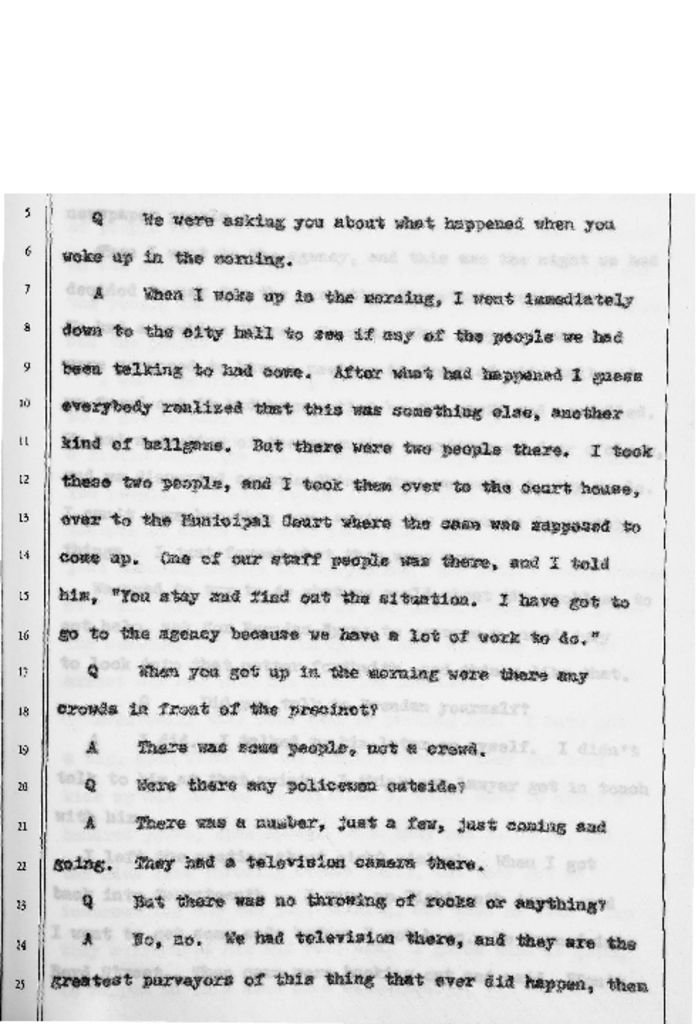

Witness Testimony from Timothy Still, President of the UCC, before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders hearings. Still describes a meeting of the UCC on Thursday July 13, 1967 in which “We moved to do what we could about the problem, to get help, ask for Brendan Byrne to convene a grand jury to look into that matter forthwith, and things like that.” — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository

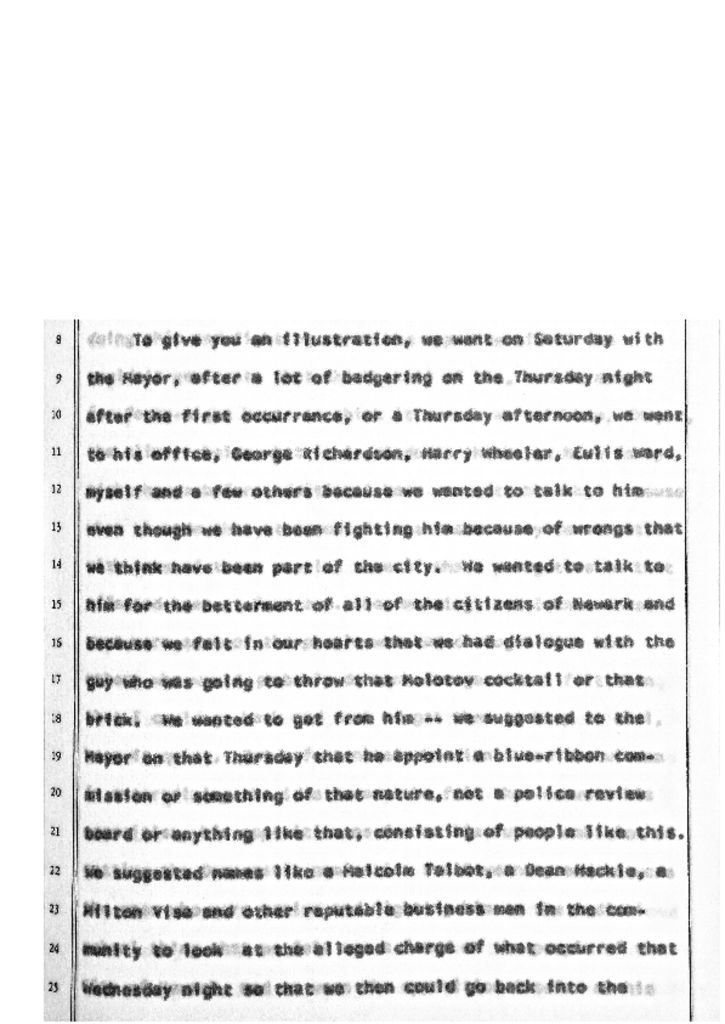

Witness testimony of Earl Harris before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders on December 8, 1967. In his testimony, Harris describes meeting with Mayor Addonizio on Thursday, July 13, the day after John Smith was arrested and beaten by Newark Police officers. At the meeting, Harris, George Richardson, Harry Wheeler, and Eulis “Honey” Ward discussed possible mayoral responses to the events of July 12 to avoid further violence. — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository

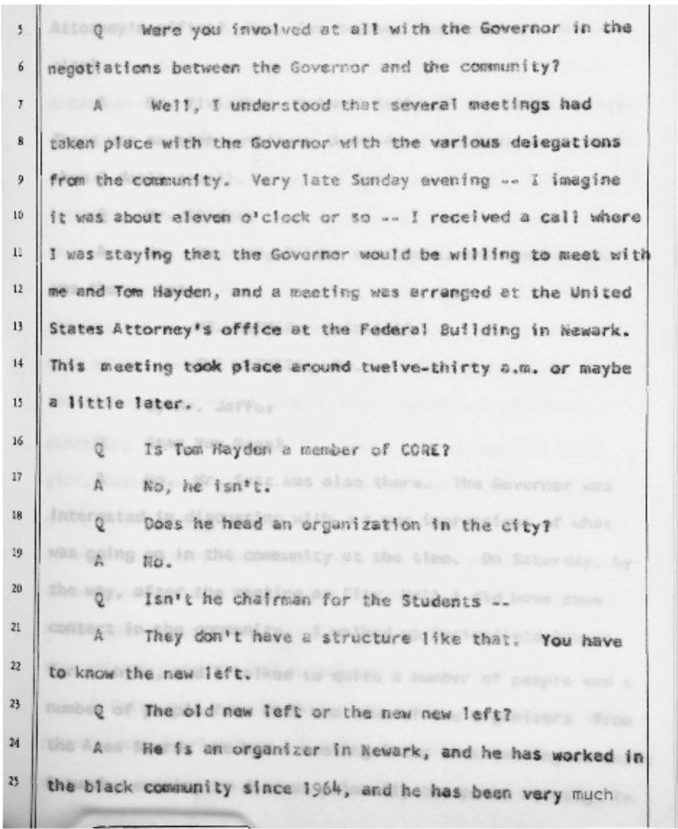

Witness Testimony of Robert Curvin before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders. In his testimony, Curvin describes a meeting with Governor Hughes, Tom Hayden (NCUP), and others on Sunday July 16, 1967 to discuss “impressions of what was going on in the community at the time.” Community leaders, such as Curvin, acted as intermediaries betwen government officials and Newark residents during the 1967 rebellion through meetings like this. — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository

Civil rights leaders and community organizers hold a press conference on July 16, 1967 to present a statement of demands to city and state officials. From left to right: Jesse Allen (NCUP), James Hooper (CORE), Donald Tucker (CORE), Marion Kidd (UCC), and Phil Hutchings (SNCC). — Credit: Newark Public Library

Statement of immediate and long term demands of residents of Newark issued on July 16, 1967. The statement was a cooperative effort of community organizations in Newark, including the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP), the United Community Corporation (UCC), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). — Credit: Newark Public Library