Education

Almost all Newark’s schools were overcrowded in the 1960s, and many were aging with obsolete structures built at the turn of the 19th century. Rehabilitation or replacement costs were estimated at about $200 million. School enrollment had increased by 18,000 to 20,000 pupils, and in 1966, the schools were short 6,052 spaces. By 1967, the shortage was closer to 10,000 pupil stations in the elementary schools. In 1961, 55% of Newark’s pupils were black and 4% were Spanish speaking; in 1966, the ratio was 69% black and 7% Spanish speaking. This rapid and massive shift in pupil population posed staggering problems reflected in low performance on standardized tests, as the children of this newer population had been ill prepared wherever they came from, or in the Newark public schools.

Nor was the Newark Public Schools interested in hiring black teachers and administrators. Out of 3,500 teachers in 1967, 1.4% of them were black and a majority of black teachers held temporary teaching certificates and served as substitutes. In 1968, there were no black principals and only one vice principal. Most of the black teachers lived in Newark, while the majority of the white teachers lived outside of Newark.

It was in this environment that the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Organization of Negro Educators (ONE), the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP), and other organizations and individuals came together to force the Board of Education to improve the schools. An observer pointed out that between 1958 and 1972, there were 102 voluntary associations representing the black community before the Board of education.

References:

Wilbur Rich, Black Mayors and School Politics: The Failure of Reform in Detroit, Gary, and Newark

Kathryn Yatrakis, ”Electoral Demands and Political Benefits” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1981)

Clip from the documentary film “We Got to Live Here,” in which an African American student describes the type of relationship he had with his teacher in the classroom. The student explains how his teacher could not relate to the living experiences of the students and stifled the intellectual curiosity of the students by threatening punishment for disagreeing with him. — Credit: Robert Machover

Explore The Archives

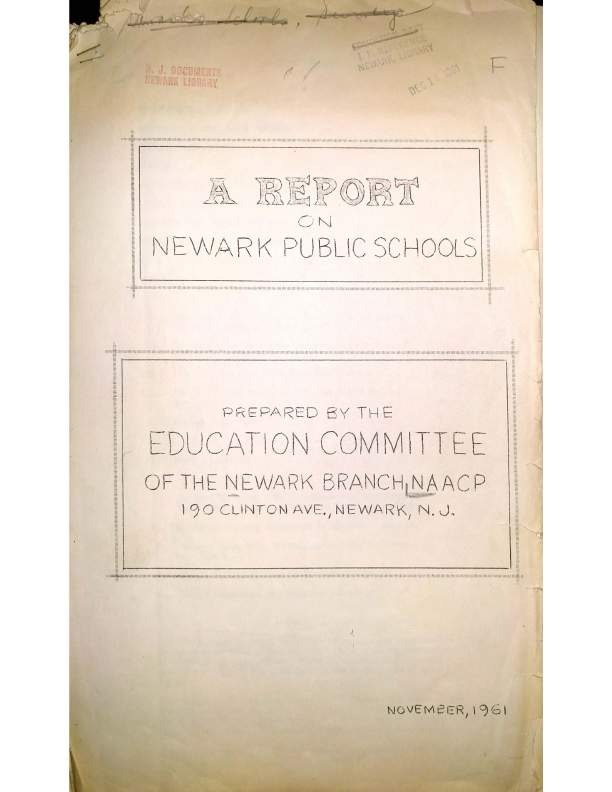

Report on the Newark Public Schools prepared in November, 1961 by the Education Committee of the Newark Branch of the NAACP. The 29-page report was the result of an eleven-month study of conditions in the city’s school system, covering issues such as academic standards, assignment of substitute teachers to full-time classrooms, and bias in vice principal examinations. — Credit: Newark Public Library

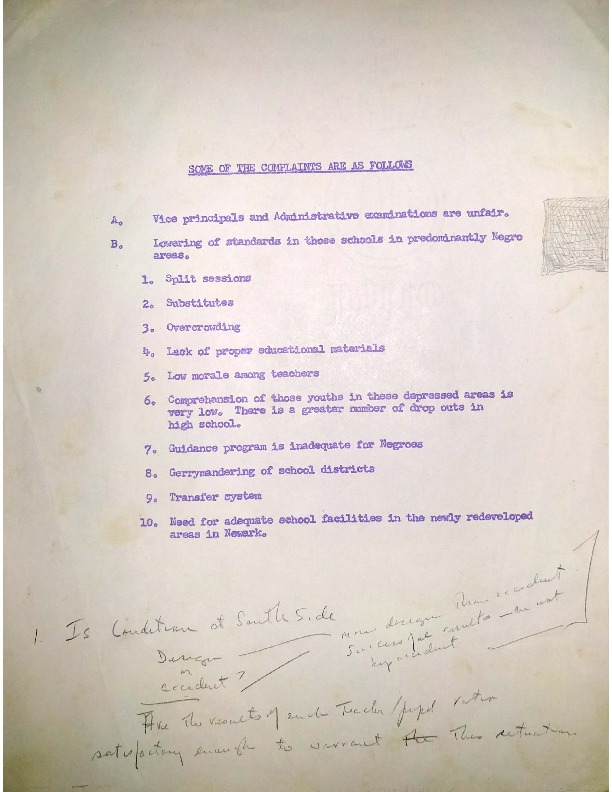

List of complaints against South Side High School presented to the Newark Human Rights Commission. In their notes, one of the Commission members raises the question of whether the conditions at South Side are by “design” or by “accident.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

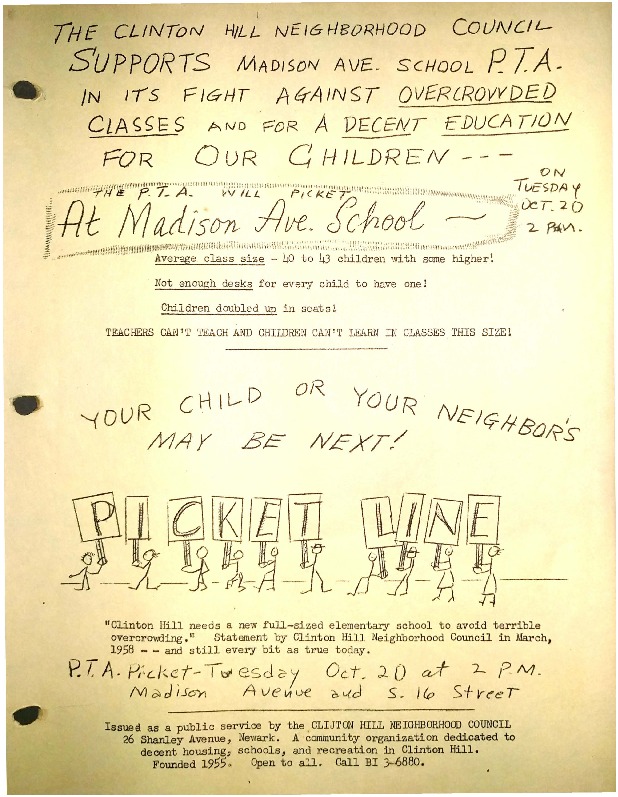

Flyer distributed by the Clinton Hill Neighborhood Council calling for a picket at the Madison Avenue School on October 20, 1964 to protest overcrowded classes. Overcrowing in classrooms was one of the most common complaints of Newark communities against the public school system that was badly in need of more buildings to accommodate its growing population. — Credit: Newark Public Library

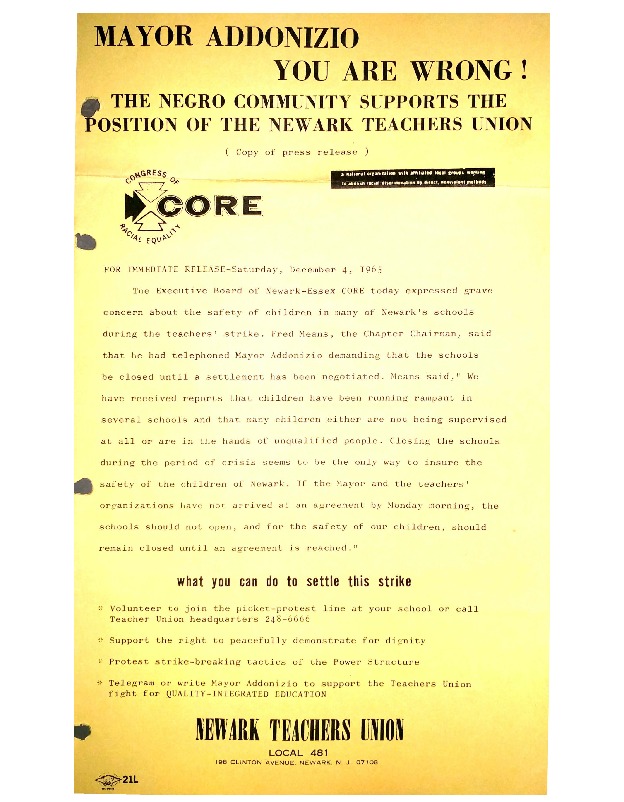

Flyer distributed by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to encourage support for the Newark Teachers Union strike in December, 1965. — Credit: Newark Public Library

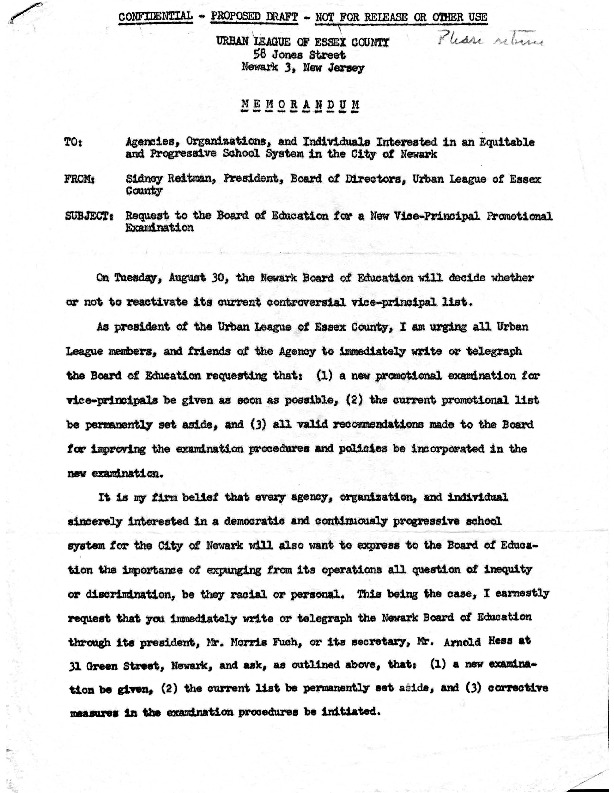

Draft memo from Sidney Reitman, President of the Urban League of Essex County, calling for support in requesting a new vice-principal promotional exam from the Board of Education. Racial discrimination in the hiring and promotion of school employees was a widely cited complaint against the Newark Public Schools by the city’s African American communities. — Credit: Newark Public Library

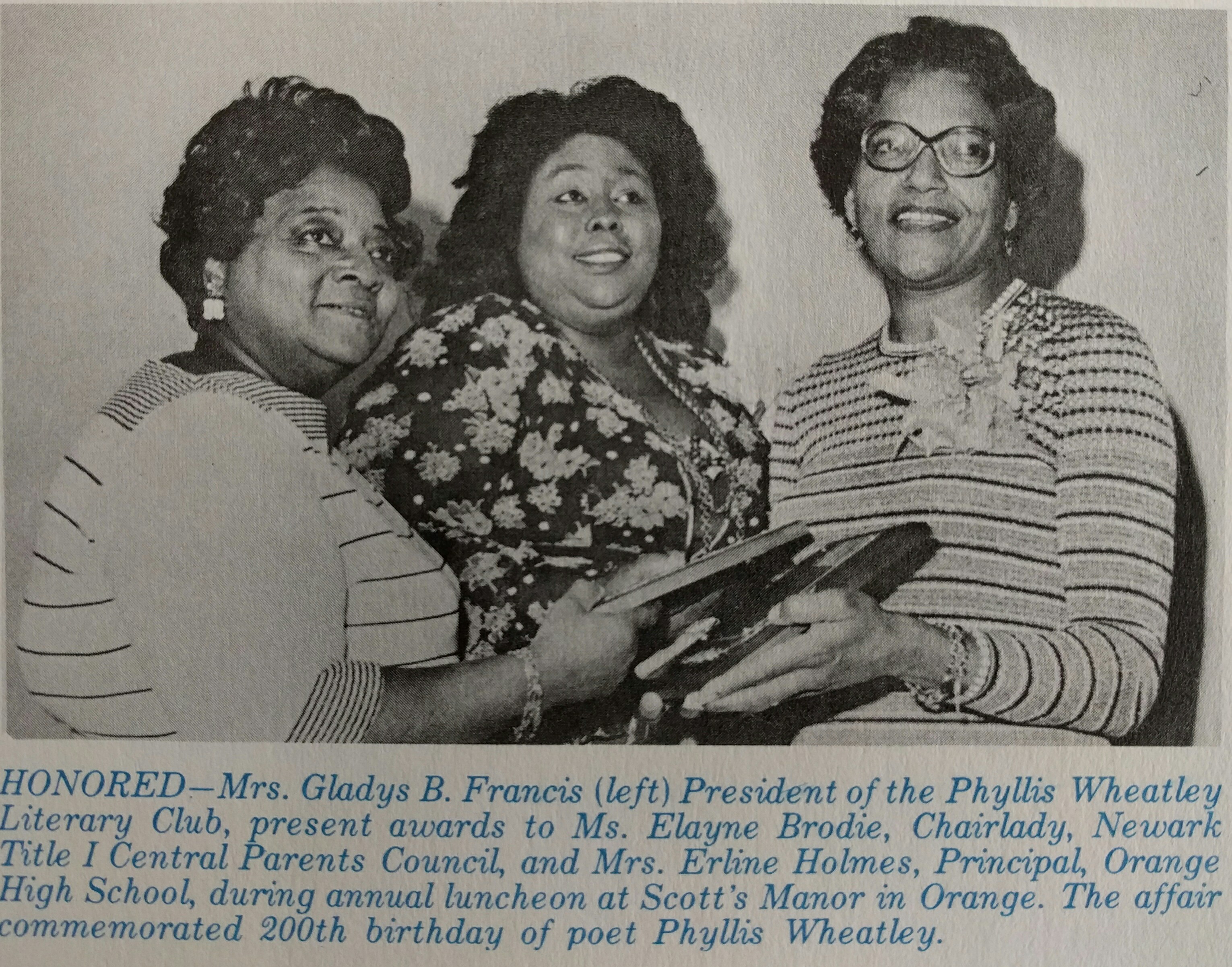

Pictured in the center of this photograph is Elaine Brodie, who was a tireless advocate for educational equality in Newark during the 1960s-1970s. — Credit: Newark Public Library

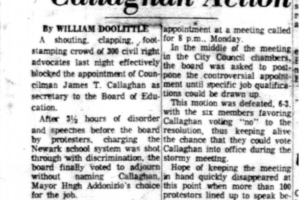

The Parker-Callaghan Fight

In early 1967, Mayor Addonizio urged the appointment of Councilman James T. Callaghan as the secretary (business administrator) to the Board of Education. Callaghan only had a high school degree. On the other hand, the NAACP, under new leadership of Sally Carroll, as well as Fred Means, the president of the Organization of Negro Educators, and the vast majority of black organizations and individuals supported Wilbur Parker, the first black certified public accountant in the state of New Jersey, and the city budget director, for the job.

“For several months in 1967,” Robert Curvin recalled, “at every school board meeting, CORE and other groups, also backed by white community leaders from the South Ward, as well as church leaders, staged vehement protests that disrupted the conduct of board business.” Many community advocates signed up and spoke at the Board of Education meeting on June 28th when the appointment was to be made, while hundreds cheered them on at a meeting that lasted until 3:00 AM. During the meeting, civil rights activists took over the seats of the board of education members while they adjourned to deliberate on the appointment.

Because of the uproar, Addonizio backed down, and his appointed board decided to keep Arnold Hess, the man already in the job. But the damage had been done; tensions were at a fever pitch. And there was unity from across the full spectrum of the black community. Even Addonizio’s supporters in the Black Political Class shut up publicly and silently questioned why Addonizio did that. In some cases they defected to the insurgents.

References:

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Sharpe James explains the anger of Newark’s Black communities over the Parker-Callaghan Fight. The Parker-Callaghan Fight is credited as one of the precipitating factors of the 1967 Newark rebellion. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

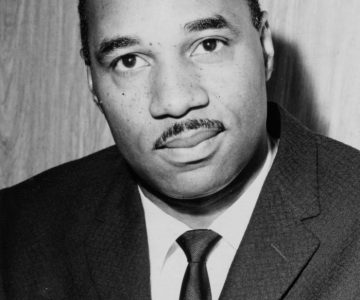

Portrait of Wilbur Parker from 1962. — Credit: Newark Public Library