Civil Rights and Electoral Politics

Irvine Turner and his supporters marked the beginning of the Black Political Class in Newark. Turner, Larrie West Stalks, and others constituted the leadership of the black community that joined in coalition with Italians to bring about the election of Hugh Addonizio in 1962.Upon his election, and his recognition that city hall was a major target for protest, the Mayor’s response was to appoint several blacks to governmental positions in an effort to diffuse and accommodate the growing pressure from the African American community for equal treatment with the white community. Larrie West Stalks became the highest-ranking appointee, but the others held few major policy making positions.

But they had jobs. And for whom the bell tolled in this regard, Addonizio expected absolute loyalty—at the expense of the rising tide in favor of the rising tide of “civil rights.” Assemblyman George Richardson lost his position on “the line” at re-election time and his job at city hall for siding with the community on the issue of police brutality in 1963.

More often than not, his employees and supporters were compelled to not only refrain from civil rights participation, unless it was directed South, but were also expected to run interference for and support his program in Newark, despite the growing protest in the community for more of everything. The Black Political Class grew under Addonizio and its usefulness as a tool to divide and conquer reached full bloom under his leadership. He said in essence, “If you work for me, you have to choose. And the choice might be a heavy lift, and certainly involve confrontation on the Mayor’s behalf with your neighbor and friends.” Addonizio had his Negroes out front to confuse and divide the community, perhaps even moreso than the police who broke up the meetings, or the white politicians and appointed officials who cast an opposing view. There would be no Bull Connor in Newark, no George Wallace, just an appearance of a liberal white mayor presiding over a city of calm where reasonable people differed. There is a song that sings:

You gotta serve Somebody

It might be the Devil

It might be the Lord

But you gotta serve Somebody

Nowhere was the effectiveness of this strategy worked out more effectively than with the Addonizio takeover of the NAACP. Yes, the grandfather of all Civil Rights organizations belonged to Hugh J. Addonizio for a while. The Black political class was like a filter for white power. It lessened the full impact of the message of resistance and rebellion, coming from the Newark community organizations. It filtered democracy, and the full force of “Freedom Now,” with language to their Newark constituency to go slow, to have patience. “We’ll work things out in decency and order; we’ll get something for you and yours.”

The louder the roar of the mighty ocean, the more the power structure bent over to appease and keep that filtration system in order. It became more elaborate, and more deadly. Why deadly? The Bible says in Proverbs 29, “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” It was resistance that propelled Irvine Turner and Honey Ward to fight their way into the political system, starting with a vision of independence. Or did they always have a vision of cozying up to the power brokers at City Hall and Essex County? Coalitions are fine but the conditions of membership should change as circumstances change. The new Black political class failed to reassess the ever-evolving majority population, and to take advantage of the winds of change based on direct action, coming from the South and the North. It was more important to maintain their comfortable yet limited positions of patronage and perks with Addonizio and/or the Essex County Democrats. Why didn’t they join with more militant voices for Civil Rights in upping the ante for cooperation with the white power brokers throughout the state? Why didn’t they give up a little temporary comfort for long term and more widespread gain? Some eventually did. Honey Ward fought the Medical School land takeover alongside one of his district leaders, Louise Epperson, and later joined the United Brothers; James Threatt, Director of the Newark Human Rights Commission, gave the community as much information from the inside as he could.

Civil rights organizations were threats to Addonizio, and perceived as such to the blacks that clustered around him. Anytime an issue was raised, such as police misconduct, landlord exploitation, or job discrimination, the Black Political Class was there to distort and dilute the message and the impact.

The story of Newark, therefore, is one of conflict not just between blacks and whites, but blacks joined by whites against blacks on behalf of whites. This was the North, and one of the main reasons why the issues were indeed “more complex.”

References:

Junius Williams, “Allies and Adversaries,” Unpublished Chapter from Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

Clip from an interview with community activist and organizer Derek Winans, in which he discusses how the civil rights movement in Newark quickly melded with politics. He recalls how the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) began working with George Richardson in 1965 as they built a political alliance for campaigns that year and in 1966.

Clip from an interview with Calvin West, Newark’s first African American Councilman-At-Large, in which he describes the political impacts of Irvine Turner’s 1954 election to the Newark City Council. West cites the election of Turner in 1954 as bringing about “a small change,” but one that began the process of Black political empowerment in the city of Newark.

Clip from an interview with community leader and politician George Richardson, in which he describes how the Civil Rights Movement in Newark impacted the political systems of the city during Mayor Addonizio’s administration. Shortly after Mayor Addonizio was elected to office in 1962, massive demonstrations against hiring discrimination began at Barringer High School in 1963, marking the beginnings of sustained civil rights activity in Newark.

Explore The Archives

Campaign brochure for Hugh Addonizio’s 1962 mayoral campaign in Newark. Addonizio ran against the incumbent, Leo Carlin, that year after serving fourteen years as a Congressman. — Credit: Newark Public Library

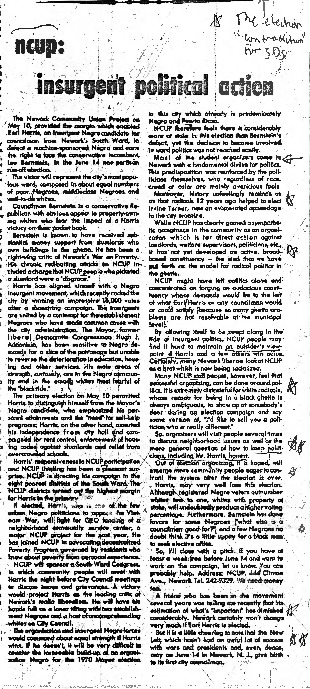

Position paper from the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) regarding the civil rights organization’s “insurgent political action” during the 1966 campaign in Newark. Members of NCUP, an affiliate of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), had conflicting views about the organization’s involvement in electoral politics. — Credit: Junius Williams Papers

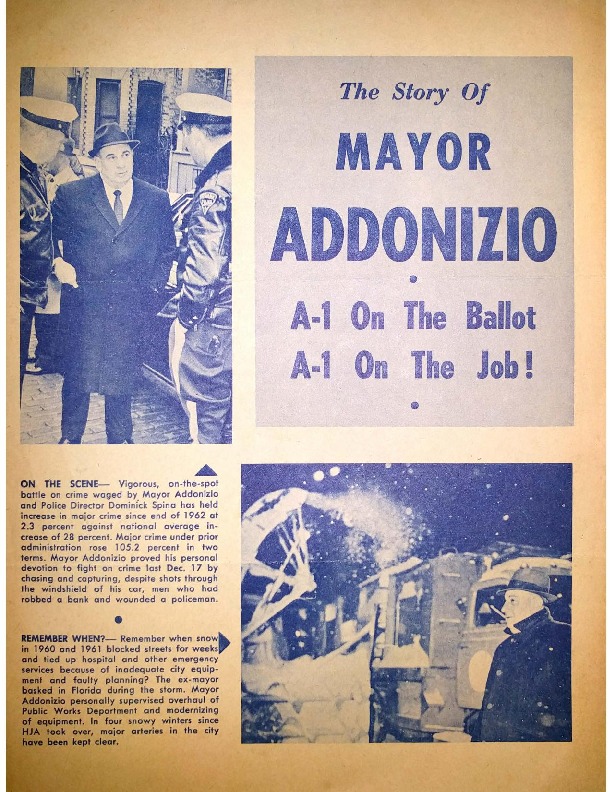

Campaign brochure for Mayor Addonizio’s 1966 mayoral campaign in Newark. Addonizio ran as the incumbent in the campaign against former mayor Leo Carlin and political newcomer, Ken Gibson. — Credit: Newark Public Library