THE POWER OF THE VOTE

Throughout the 1930s and ‘40s, the increase in the population of African Americans was not ignored by the local politicians, but there was only token recognition of their presence by the white ethnic bosses. At that time, black people represented only 10% of the population. By the 1950s though, African Americans constituted 17% of Newark’s population, with numbers continuing to grow—most of them confined to the Third Ward.

Both parties reacted. Up until the election of Democrat President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932, and in three successive elections thereafter, black people were expected to vote Republican, the party of Abraham Lincoln. Each party vied for black District Leaders in the Third Ward. Prosper Brewer was the Republican Ward Chairman in the 1930s to the 1950s, when he was replaced by Bill Stubbs. Charles Matthews and Mrs. Larrie Stalks were the first Chairman and Vice Chairwoman of the Democratic Party. Both parties successfully ran black candidates for county Freeholder and state Assemblyman positions. But there were no African Americans among the five Newark Commissioners, representing the strongest white ethnic groups at that time. After each election they decided who would be Mayor and parceled out the various departments among themselves. The Commission form of government established in 1917 to maintain ethnic harmony and curtail corruption, allowed each of the 5 members to become the executive of his department, and collectively serve as legislators. Each Commissioner built his political organization on the strength of patronage and control of contract dollars.

African Americans were not represented at this table and thus got none of the spoils of membership. The black vote was concentrated in the Third Ward and Commissioners were elected citywide. Hence they could never get enough votes to win a seat. The New Jersey Afro-American said the Commission form of government, “was for corrupt political machines and race baiters; it has been extremely difficult for Newark’s 76,000 colored citizens to have a voice in municipal affairs for thirty years.”

————

African Americans were not represented at this table and thus got none of the spoils of membership.

————

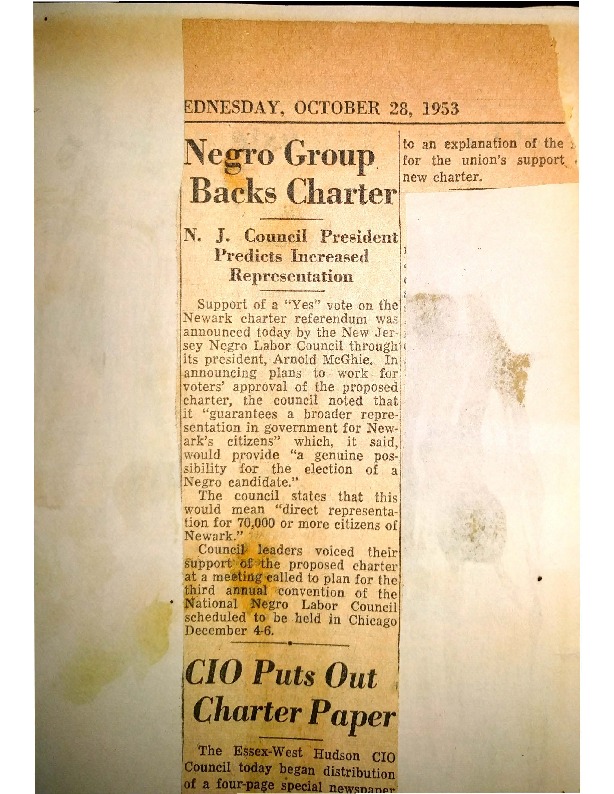

In 1953, tired of the corruption and indictments of city officials, representatives of labor, business and professional groups met to reform city government. A planning committee was set up, which contained no African Americans. Black leaders from the Urban League, the NAACP and other professionals supported the idea of charter change, while more traditional black politicians did not. The absence of black participation did not bode well, but the middle class reformers supported the change.

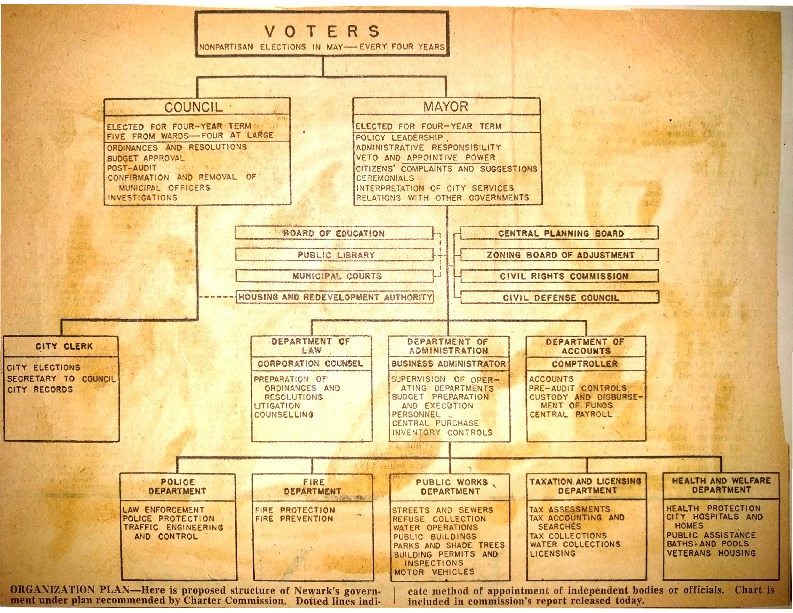

The ad hoc study group proposed a change from the commission form to a strong mayor, nine-member city council form of government under the NJ Faulkner Act. Four members would be elected at large, and one from each of 5 wards. The new form was adopted in November of 1953.

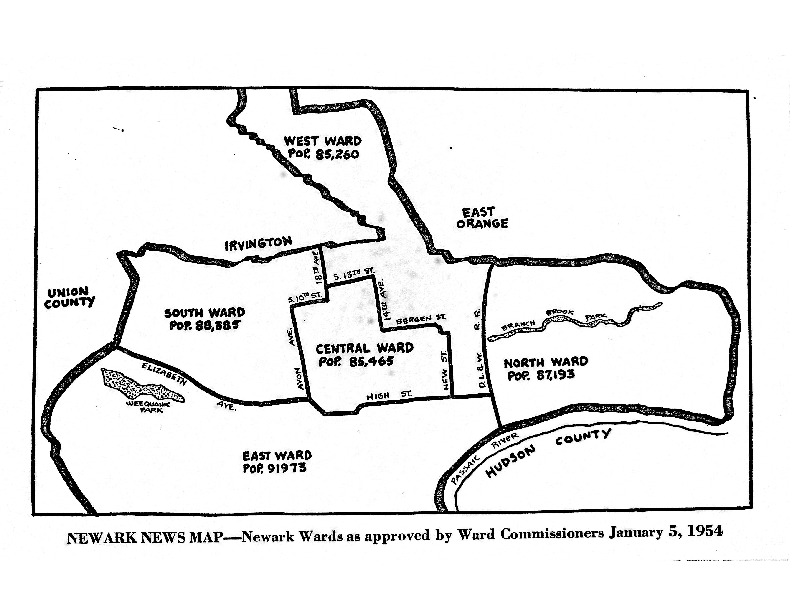

A five-member election committee met to draw boundaries for the new wards. The Third Ward containing most of the African Americans was configured into a set of boundaries where black people would be out numbered by whites.

African American leadership protested, led by Tim Still, a public housing leader, and Larry Coggins, head of the Negro Labor Vanguard. Still went to Washington DC to consult with the Census Bureau about the accuracy of the population, and found out the figures supplied by the city clerk and used by the commission were incorrect. A lawsuit was filed; a settlement reached. The Central Ward was reconfigured to provide a decisive majority of African Americans. A seat on the new City Council was thus assured.

Clip from an interview with former Deputy Mayor of Newark Paul Reilly, in which he describes the ethnic struggles for political power from the 1930s-1960s. Reilly, an Irish-American, served as Deputy Mayor during the administration of Italian-American Mayor Hugh Addonizio, from 1962-1970.

Clipping from an unmarked newspaper in 1949 covering Irvine Turner’s urging of African American voters not to vote in the gubernatorial election that year unless one of the candidates promised benefits to Newark’s Black community. — Credit: Newark Public Library

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

“Voters to End Rule by Commission: Charter Group Cites Major Advantages Mayor-Council Rule Would Bring to City,” New Jersey Afro-American, August 15, 1953

Stanley Winters, “Charter Change and Civic Reform in Newark, 1953-54,” NJ History 118 (2000)

Explore The Archives

Political cartoon from the Newark Evening News in 1953 about Newark’s proposed charter change from a commission form of government to a strong mayor form. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Map of possible ward lines under the mayor council plan drawn up by the Newark Charter Commission in August, 1953. Some of the city’s African American leadership, including Tim Still and Larry Coggins, protested these boundaries that made Black voters a minority in the Central Ward and fought to have the ward lines changed. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Map of Newark Wards as approved by Ward Commissioners on January 5, 1954. The original ward lines were re-drawn after African American leaders, including Tim Still and Larry Coggins, protested the boundaries that made Black voters a minority in the Central Ward and fought to have the ward lines changed. — Credit: Newark Public Library

“Here is proposed structure of Newark’s government under plan recommended by Charter Commission. Dotted lines indicate method of appointment of independent bodies or officials.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

Clipping from an unmarked newspaper on October 28, 1953 covering the support of the New Jersey Negro Labor Council for a “Yes” vote on the Newark charter referendum. — Credit: