The Newark Agreements and the NCTTC

In Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power, Newark Historian Junius Williams offered the following reflection on the 1967 Newark Rebellion: “the violence that no one wanted became useful in changing the power relations.” Nowhere is this more truthfully reflected than in the Newark Agreements, signed in April 1968 following the Rebellion. The Governor’s Commission to investigate the causes of the Rebellion found that one of the contributing factors to the Rebellion was the plan to displace thousands of residents in order for a new medical school to take possession of 150 acres of land in the predominantly-Black Central Ward. As a result of the hard work of community organizers and the leverage provided by the Rebellion, the land acquisition for the Medical School was reduced from 150 to 57.9 acres. Additionally, the community successfully negotiated a provision in the Agreements that required Black and Puerto Rican workers to comprise at least 1/3 of all journeymen and 1/2 of all apprentices in each trade on the construction site, as Newark’s population rose to 52% Black and 9.5% “Spanish-speaking” at the turn of the decade.

Additionally, as a result of the Agreements, the State provided funding to create the Newark Construction Trades Training Council (NCTTC). Under the leadership of Chairman Gustav Heningburg, Executive Director James A. Walker, and Director of Operations George Fontaine, the NCTTC was established as a “recruitment, training and referral work force.” The first year’s start-up and operating costs came to almost $2 million, with a yearly operating budget of more than $750,000 from that point on. During the six years of construction for the medical school complex, New Jersey Magazine reported in 1979, the State contributed $10 million to the NCTCC, $5 million of which went to salaries for trainees on site.

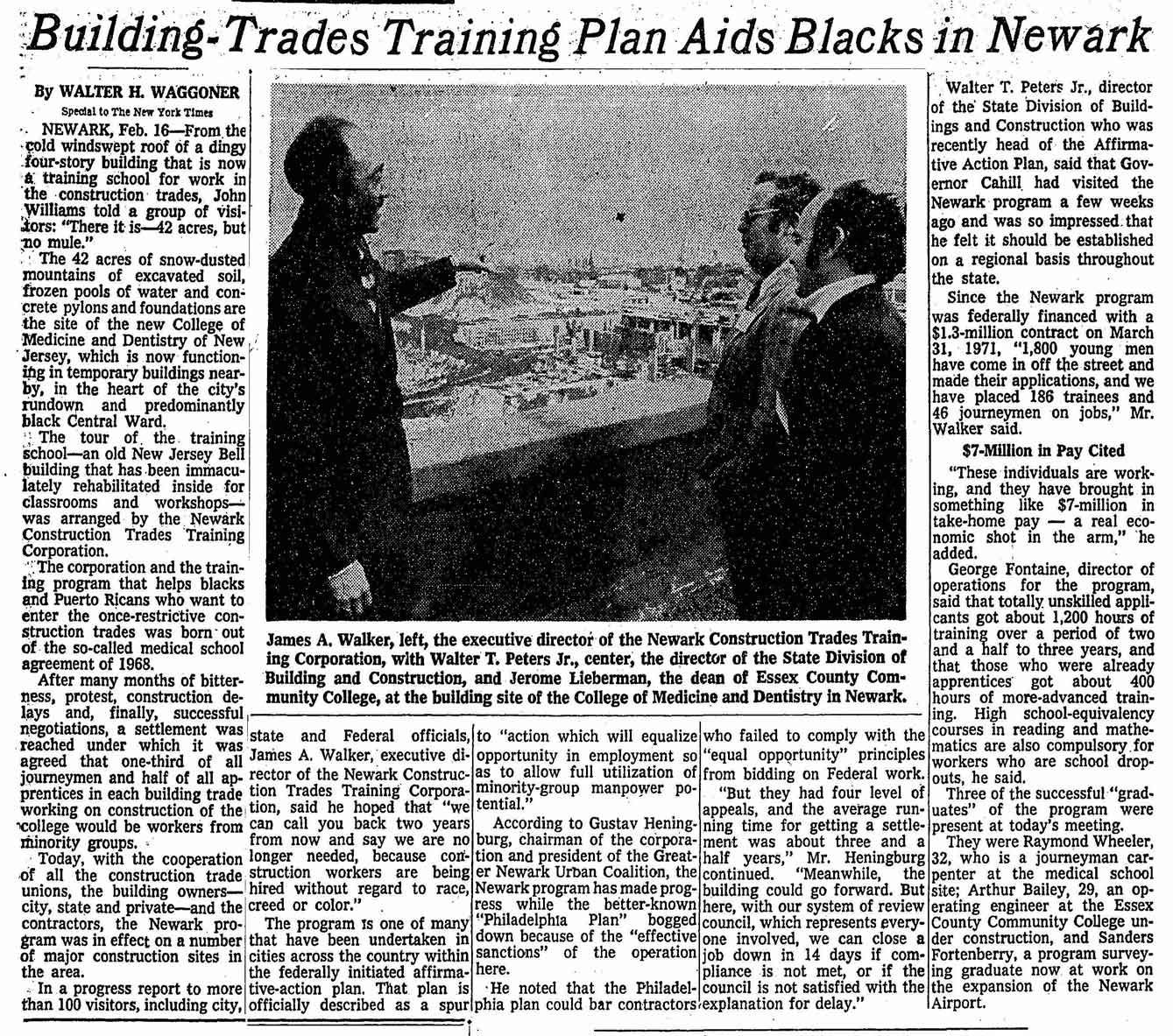

The training function of the NCTTC was noted as a critical component of the plan. Individuals who successfully completed the training program and were employed under the plan were required to be admitted into union membership. Black workers were often kept out of unions by discriminatory policies, which made unions major targets for protests during the Civil Rights Movement in the north. By 1973, Walker stated that 1,800 young men had completed applications and 186 trainees and 46 journeymen were placed on jobs, together bringing in about $7 million in take-home pay. Fontaine noted that unskilled applicants received about 1,200 hours of training over 2 ½ years, in addition to the required high school equivalency courses for those without degrees. Those who were already apprentices received about 400 more hours of advanced training.

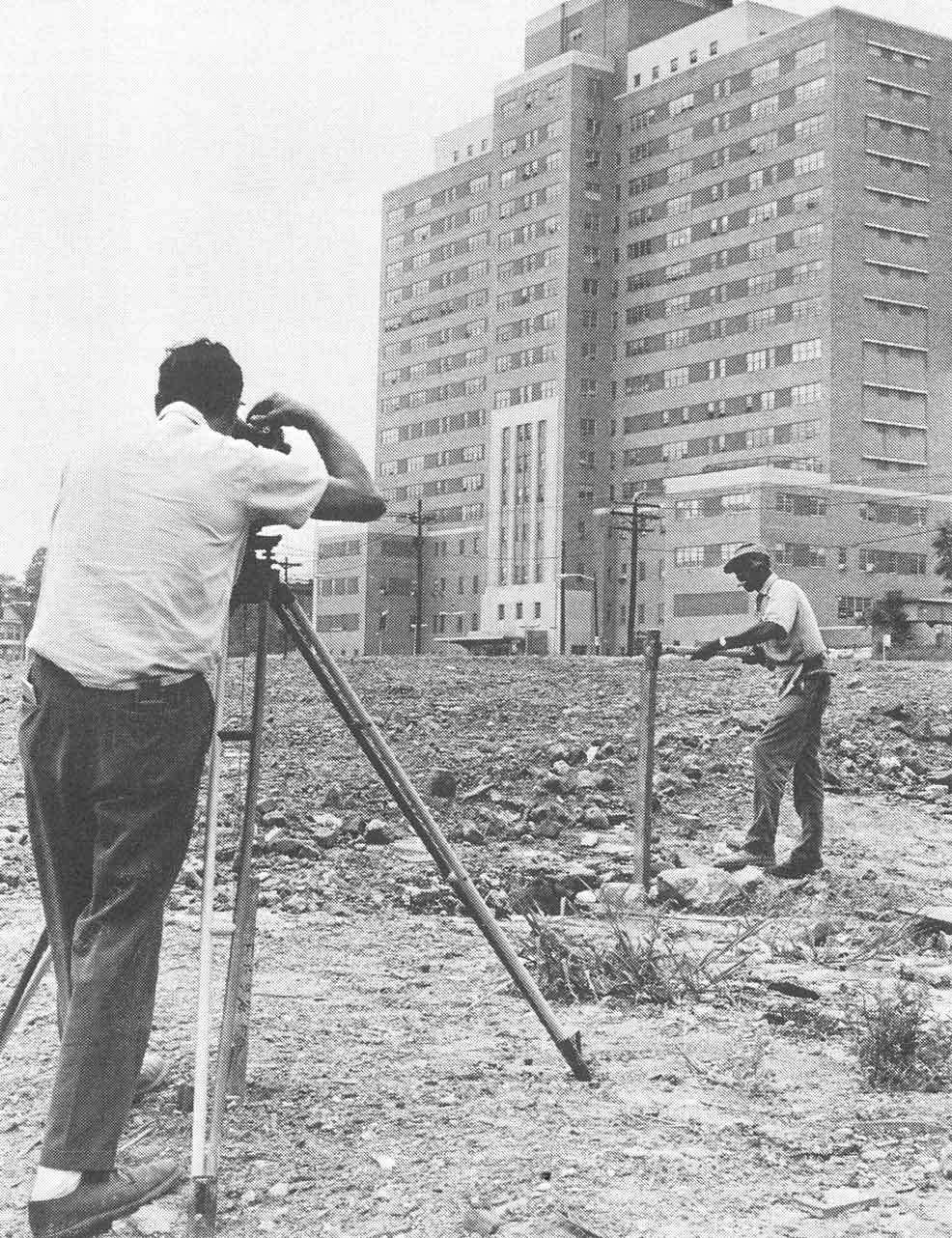

In addition, the Newark Agreements mandated the formation of a Review Council to ensure compliance. Composed of representatives from the community, the state, labor unions, contractors, and federal agencies, the Review Council was tasked with overseeing the implementation of the Medical School Agreement’s affirmative action program. The Council required that all pre-contract awards included projected manpower steps that would meet the Council’s standards. If not, the contractors would be required to undertake an affirmative action program, or else be considered in breach of contract. In the summer of 1968, the Review Council shut down the construction site for three weeks to ensure that contractors and labor unions adhered to the affirmative action program of the Newark Agreements.

In the first few months of construction of the medical school, Blacks outnumbered whites in the total construction force. However, in the skilled trades positions, drastic differences were evident. This discrepancy was one of the driving forces of the NCTTC’s work. In 1970, Gus Heningburg testified before the U.S. Labor Department’s Office of Federal Contract and Compliance that there was a substantial lack of minority-group workers in the building trades unions. However, Heningburg boasted that a strength of the NCTTC was that they could “close a job down in fourteen days if compliance [was] not met or if the (Review) council [was] not satisfied with the explanation for the delay.”

Despite its successes, perhaps the greatest disappointment of the Newark Agreements was the apparent lack of sustained government support. According to New Jersey Magazine editor Anthony DePalma, “although the New Jersey anti-discrimination law was passed in 1975, the legislature did not provide a sufficient budget or enough staff to implement it” – making it difficult for the State to verify the number of Black and Puerto Rican workers actually employed on each job site. Unions were accused of fulfilling the numerical requirements of Newark’s Affirmative Action plan, but not allowing minority employees to actually work or learn the trade at the work site. A further investigation of the State’s implementation of the affirmative action laws found that up until 1979, the State selectively monitored construction sites and had never imposed a financial sanction against a contractor. The State’s General Accounting Office found that minorities made little progress during this time period and only increased their representation in the trades from 7.2% to 8.4%.

Ironically, taking three years to “place its own construction under the authority of the plan,” the City’s compliance and support were also critiqued. In 1978, Newark City Council called for a “good-faith effort” for contractors to comply with an administration-sponsored resolution requiring 25% of construction costs on tax abated projects be set aside for minority contractors. Heningburg opined that the “city has made no effective effort to provide opportunities for minority businesses in municipal construction projects. … The idea that a good faith effort should be all that is required is unrealistic … [the city and the private sector] haven’t [utilized minority business enterprises voluntarily] before and there is no reason to believe it will happen now without some mandatory requirement.”

As a mayoral candidate in 1969, Kenneth Gibson exhorted businessmen to support demands for minority inclusion in the unions. However, after the successful election, Mayor Gibson did not support the Newark Agreements and the NCTTC in the ways it truly needed. Instead, concurrent with the NCTTC, the City of Newark set up a similar independent training facility, known as the New Hope Development Training Corporation. This Corporation “trained people for city projects and caused ‘duplication of resources and competition for funds.”

In addition to the lack of support from within the City, the NCTTC also faced opposition at the county and state levels. In response to pressure from the white members of the Essex County local building trades council who were vying for local construction jobs, New Jersey Building Trades Council president James Grogan urged the State to discontinue its support of the NCTTC. Such pressure from construction unions effectively compelled Governor Brendan Byrne to pull funding for the NCTTC in 1978. Realizing the program was doomed without state support, in 1979 NCTTC directors offered to “widen their services and function as a regional training and recruitment center” and add “New Jersey” to its name. However, the proposal was not successful and on July 6, 1979, the NJNCTTC closed its operations with 110 trainees remaining in the program. These trainees were left with a $162,000 contract from the City of Newark, to be trained in less coordinated training programs and no guarantee for an opportunity to actually work in the lucrative construction field that was then booming in the City.

References:

Willa C. Johnson, “Illusions of Power: Gibson’s Impact Upon Employment Conditions in Newark, 1970-1974,” (PhD diss., Rutgers University, 1978).

“Charges States is Soft on Hiring Practices,” Newark Evening News, September 12, 1970.

Anthony DePalma, “Affirmative Inaction,” New Jersey Magazine, July 1979.

“Building-Trades Plan Aids Blacks in Newark,” New York Times, February 17, 1973.

Agreements Reached Between Community and Government Negotiators Regarding New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry and Related Matters (As Amended), April 30, 1968.

“Federal Hearing in Newark – Probers told of bias in construction hiring,” Newark Star Ledger, March 19, 1970.

“Newark Bias Fight Halts Airport Work,” New York Times, October 30, 1971.

“Agreements to Guarantee Hiring of Minorities Signed in Newark,” New York Times

James Walker, George Fontaine, and Gus Heningburg reflect upon the Newark Construction Trades Training Corporation (NCTTC). See Vimeo for credits.

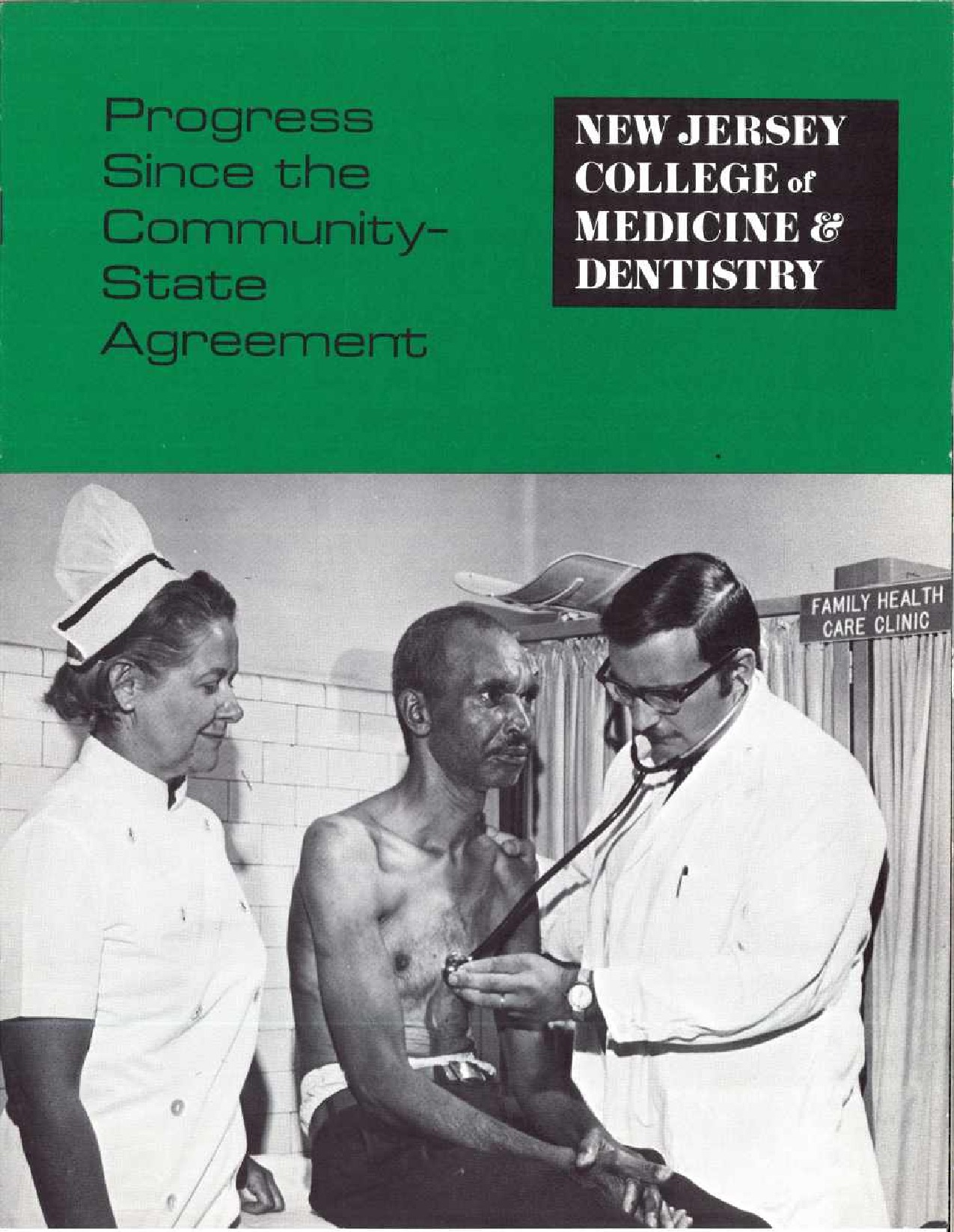

Fall 1968 Bulletin of the New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry titled, “Progress Toward the Community-State Agreement.” –Credit: Special Collections, Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences, George F. Smith Library of the Health Sciences.

The Review Council was tasked with overseeing the implementation of the Medical School Agreement’s affirmative action program. Review Council vice chairman, George Fontaine, is seated at the head of the table. –Credit: Special Collections, Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences, George F. Smith Library of the Health Sciences.

Article from the New York Times on the Newark Construction Trades Training Corporation, February 16, 1973. Pictured in the article is NCTTC executive director James Walker. Credit: The New York Times

Two men survey the construction site of the interim buildings in 1968. The Review Council shut down the construction site for three weeks that summer to ensure that contractors and labor unions adhered to the affirmative action program of the Medical School Agreements. Credit: Special Collections, Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences, George F. Smith Library of the Health Sciences.

A press release from the NJ State Senate, announcing legislation introduced by State Senator Wynona Lipman and Assemblyman Willie Brown to restore funding to the NCTTC. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Explore The Archives

George Fontaine discusses the formation, objectives, and impacts of the Newark Construction Trades Training Council. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

The “Newark Agreements” between representatives of Newark’s Black and Puerto Rican communities and government officials regarding the proposed NJ College of Medicine and Dentistry in 1968. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Clip from an interview with Gus Heningburg, in which he explains the outcomes of the Newark Construction Trades Training Council (NCTTC). –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Gus Heningburg explains how the Newark Construction Trades Training Council (NCTTC) influenced Governor Brendan Byrne’s re-election in 1974. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Clip from an interview with Gus Heningburg, in which he describes how construction delays on the CMDNJ allowed Heningurg and others to establish the Newark Construction Trades Training Council (NCTTC) to ensure the hiring and training of Black and Puerto Rican workers. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Gus Heningburg discusses the struggle to pass a New Jersey state law against employment discrimination. The law was introduced in 1974 during the fight for affirmative action in the construction industry in Newark and eventually passed the following year. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

Gus Heningburg describes the lessons learned from struggles to win equitable employment opportunities for Black and Puerto Ricans in the construction industry. –Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

Letter from Newark NAACP President Norman Threadgill to Gov. Brendan Byrne, April 18, 1978, urging continued state support for the NCTTC. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Letter from NJ Bell Telephone Company to NJ Governor Brendan Byrne, April 25, 1978, urging the reinstatement of funding for the NCTTC. –Credit: Newark Public Library