Chapter 3

The Newark experience during the decade of 1960-1970 can be reduced to one word: Conflict. Despite the presence of the New Black Political Class (elected and appointed local governmental figures, ministers, Democratic Party officials at the county and city level, and other neighborhood leaders who were rewarded by Mayor Hugh J. Addonizio’s administration for their loyalty), there was opposition to the political status quo that quite often spilled out into the street.

Why Newark? How did this opposition within the black community grow to be so sharply antagonistic to all levels of government and private seats of power in the lives of African Americans?

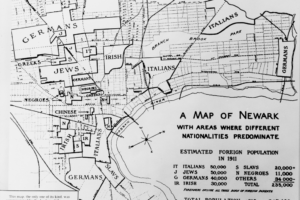

First, contrasts in equality of opportunity became increasingly stark during the 1960s. In 1950, Newark’s black population was approximately 17%, but by 1970, it reached 52.4%. In six years, 1960-1967, the city switched from 65% white to 52% black and 10% Spanish-speaking. The Italians who had previous shared power off and on with the Irish under the commission form of government, were now fully in charge of the city with an elected Italian mayor and majority city council—a reflection of their growing majority status amongst whites in Newark. They felt threatened by the growing chorus of black demands for better opportunities. Additionally, the appetite for self determination amongst African Americans only grew with each repressive measure taken by the city through its police force, along with other agencies such as the Board of Education and the Department of Welfare; it intensified with rent gouging by unscrupulous landlords, or price and credit fraud by crooked retail merchants; or with land grabs by urban renewal authorities who constantly destroyed communities in the name of profit. There was open conflict between black and whites for the formal seats of power, but more often, between the people and the police—the representatives of white power in life in the streets.

Second, the jobs that were the attraction for the second black migration from the South during and after World War II were no longer as plentiful. There were decreasing employment opportunities as manufacturing and other industries left the city with the out-migrating white population. During the 1960s, a total of 1,300 manufacturers left Newark. The jobs left in Newark, at the port area and in the downtown central business districts were reserved predominantly for whites. Conflicts arose over these job opportunities in the business community, and at agencies of city government, such as City Hall and the Board of Education.

Third, as the more affluent population (mostly white) left Newark, they were quickly replaced by a very poor population (black and Puerto Rican) that had little opportunity for mobility and depended heavily on public services. In almost every category of welfare assistance, Essex County’s expenditures were more than double of the nearest contender, Hudson County. Newark was becoming the major reservoir for the poor in Essex County, and public welfare expenditures showed it. Resistance to the increasing arbitrariness of government in the distribution of government programs resulted in more conflict between Essex County and the community of poor people and their allies.

How long was the combined white power structure willing to continue its virtual monopoly on power in Newark, with token representation in city government by a handful of the Black Political Class and their followers? How hard was the African American community willing to push for self-determination and economic parity through their organizations, many of them newly formed in this ten-year period (1960-70)? And what would happen when the desire for power and frustration from perpetual domination would go beyond the ability of the organized mechanisms of government and resistance organizations to contain the anger of the community any longer?