African Americans, Pt. 1 (Enslaved)

Historians have not pinpointed the exact date of the arrival of the first enslaved African in Newark, but there is evidence of the sale of African American slaves and enforcement of the institution of slavery in “East Jersey,” where Newark was situated, by 1680. African Americans were probably in Newark before other immigrant groups, during the Puritan’s colonization of Newark.

There was no conflict between the institution of slavery and Puritan ethics. On August 25, 1746, the New York Evening Post, advertised that Joseph Johnson of Newark planned to sell “at public (auction)….two Negro men , whom understand mining…” Bills of Sale from the Colonial period confirm the sale of African Americans to white buyers in Newark.

————

Bill of sale:

“John and Reyneir Brown of Newark NJ sell a Negro woman

and child to Josiah Hornblower (1780)”

————

By 1694 the colony had already taken steps to prohibit African Americans from handling guns, prohibiting the sale of strong drink (to Indians as well), set fines for harboring slaves, and established tight authority over its slaves in a strict legal system. A special Slave Court was established where “Negroes, other slaves, felony and murder cases were to be tried before three justices of the peace…from 1695 until 1768.”

Between 1721 and 1769, New Jersey allowed the duty-free importation of slaves, and became a haven for smugglers running slaves into New York and Pennsylvania.

By 1800, there were 12,422 slaves in New Jersey, or 5.8% of the population. By 1820, the number of slaves had decreased to 7,557 because of “gradual emancipation.” Under an act passed in 1804, slaves born after July 4, 1804 were free after serving 25 and 21 years for men and women respectively. By 1860, there were only 18 “apprentices for life.” The gradual decrease in interest in the institution of slavery had much to do with the work of black and white abolitionists and the fear held by many whites of so many slaves in the population; but also the changing nature of the New Jersey economy from agriculture to manufacturing. New white immigrants were seen as preferable to do the work in the shops and factories that abounded in Newark in the 18th century.

While it existed, slavery permeated all aspects of Newark life. The “Minutes of the Board of Trustees” of the prestigious private school, Newark Academy, dated 1792, records the following transaction:

————

“Agreed that the Rev. M. Ogden sell Negro James ,

as Donation to the Academy, to Moses Ogden,

payable in two months, with interest.”

————

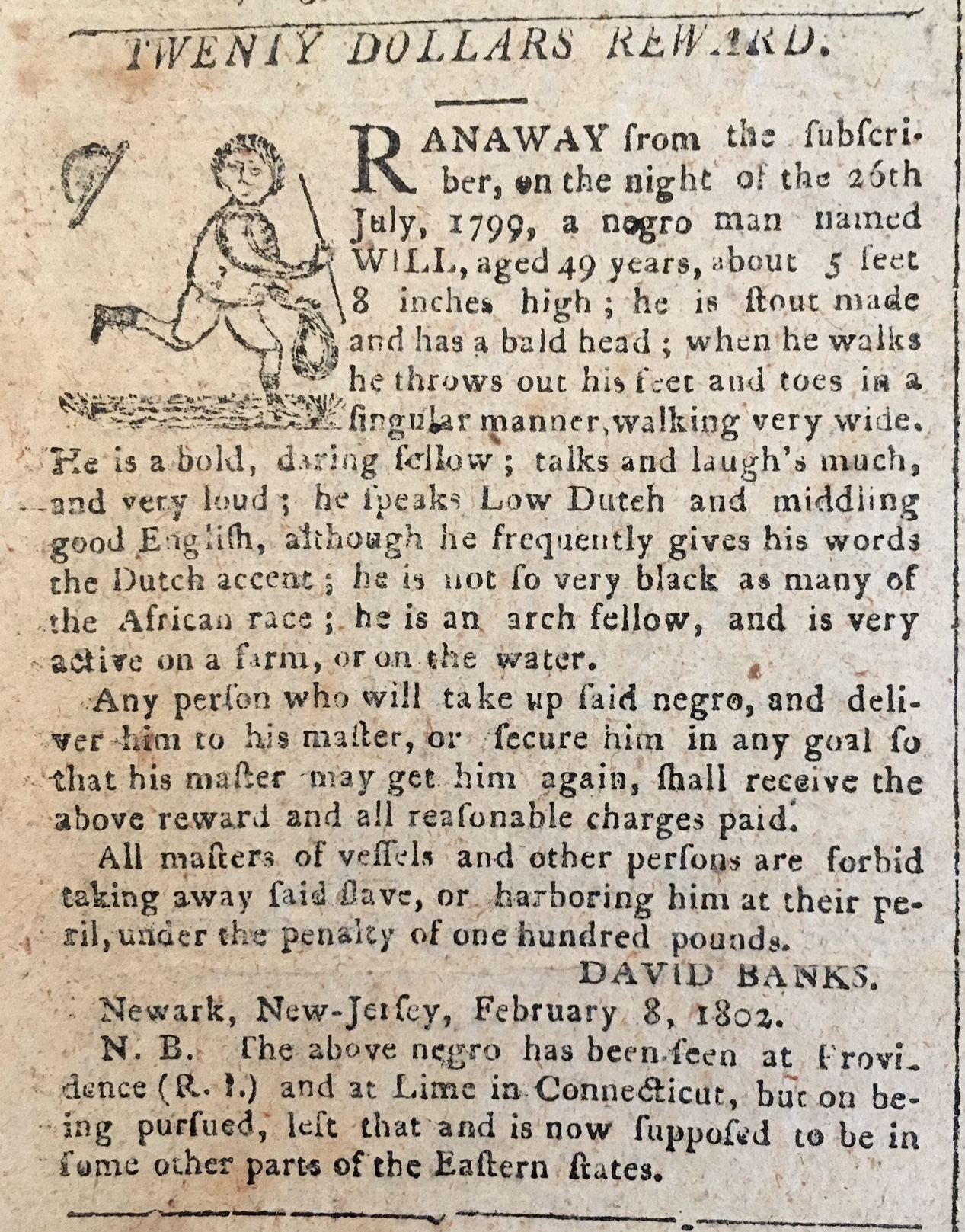

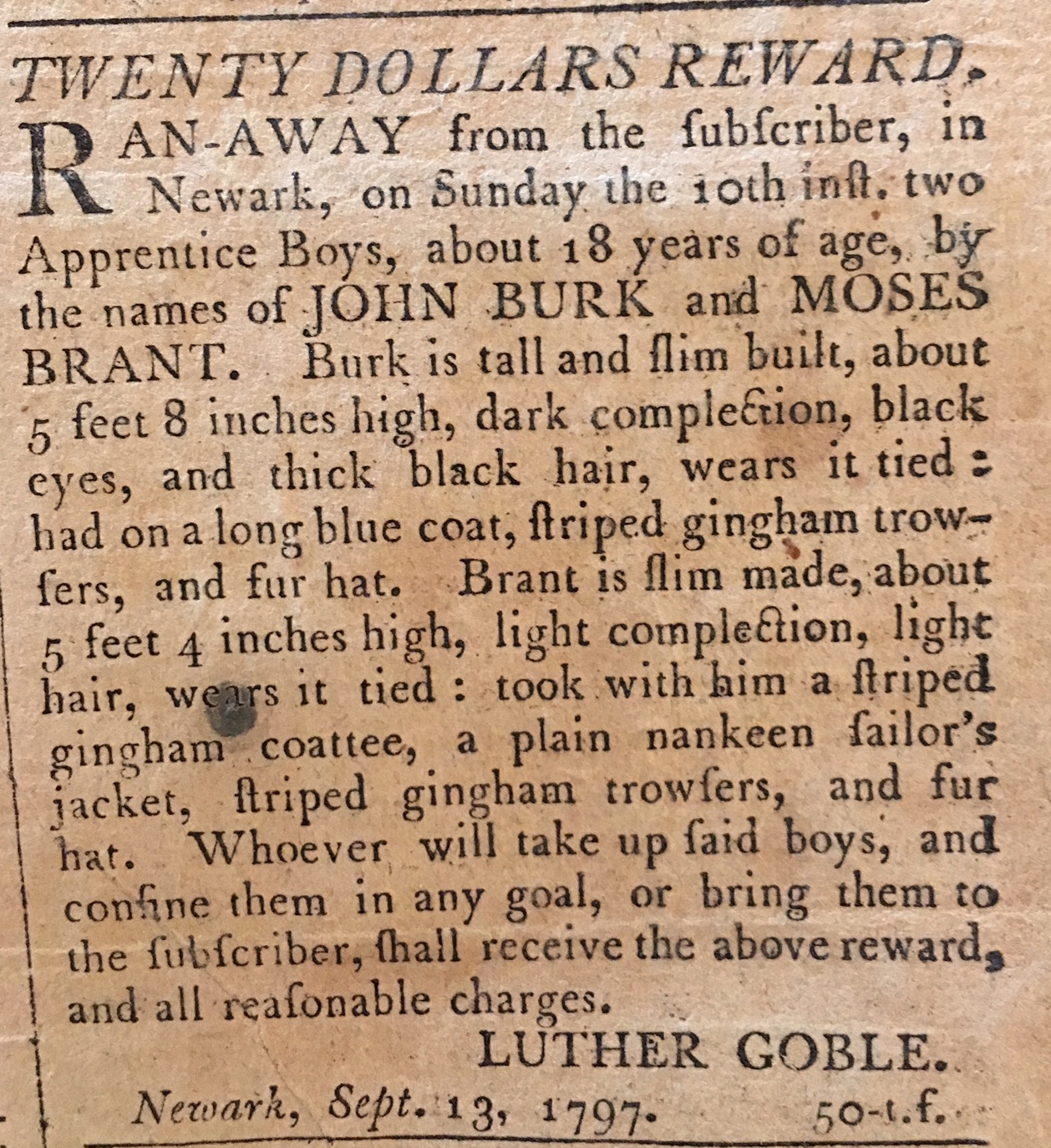

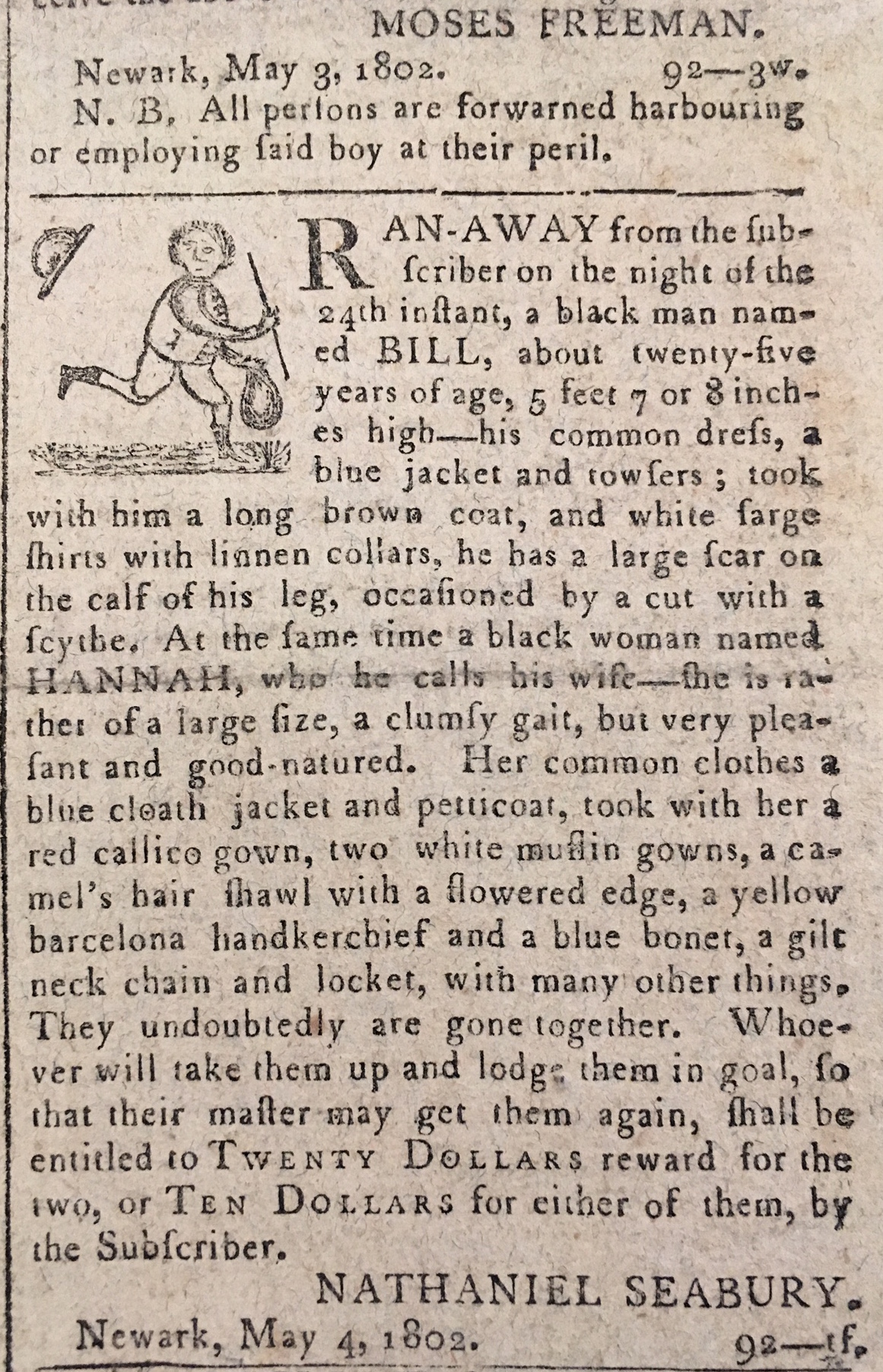

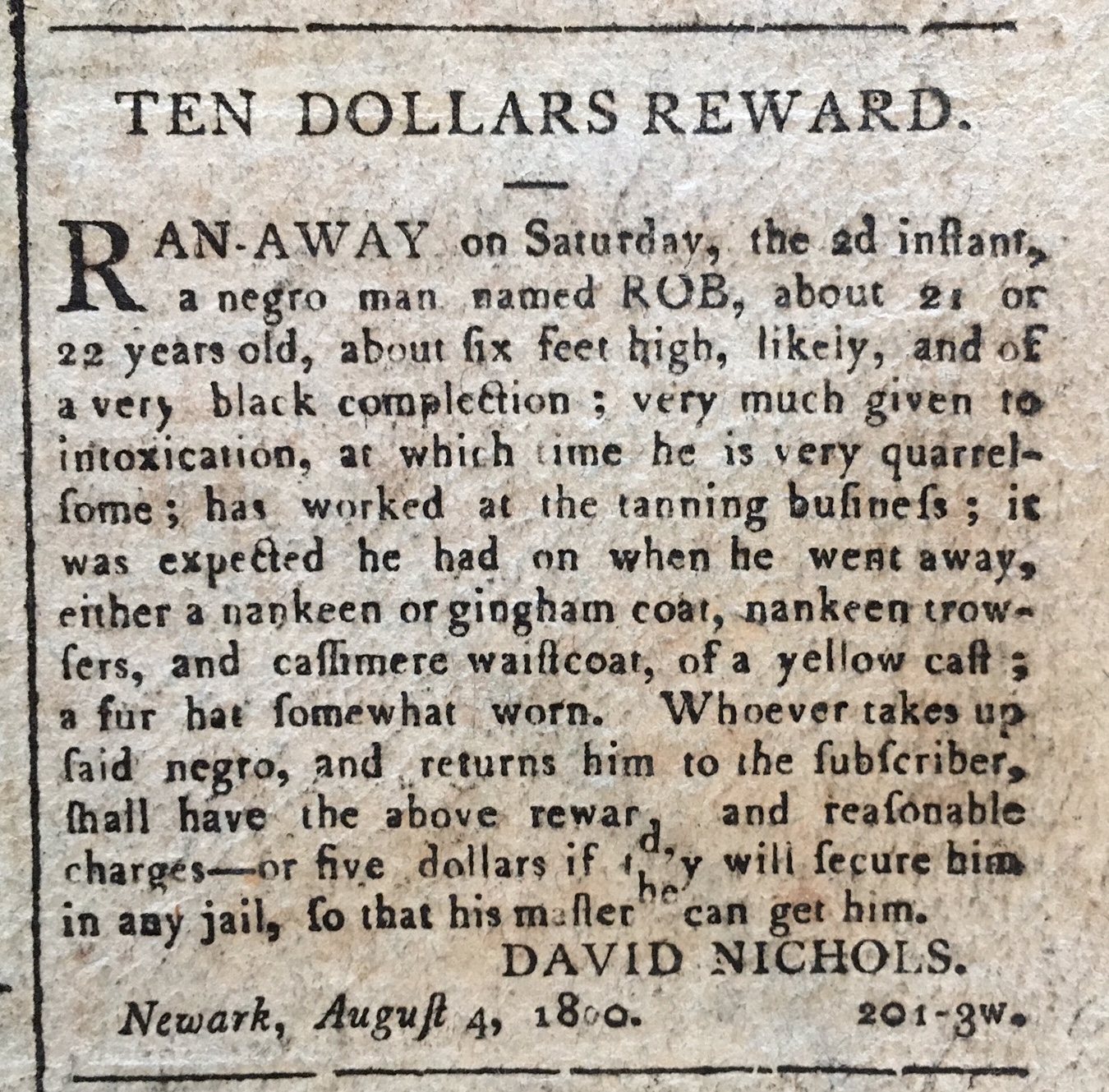

Newark slaves resisted bondage. There are many printed advertisements in the Newark Centinel of Freedom, offering rewards for the capture of escaped slaves. Slave master Emanuel Cocker advertised in the New York Gazette in 1748 for the return of

————

“Charles, aged 35 years, and speaks broken English….

Charles wore a red jacket with white metal buttons,

an old felt hat, a new tow shirt and old (pants)”

————

Slaves throughout New Jersey also “destroyed tools, animals, crops and other property. Others physically harmed their masters…As early as 1695, two African Americans were hanged and another burned alive for conspiracy and the murder of a prominent Monmouth slave holder.”

Freedom from slavery by any means necessary was the first act of empowerment by enslaved African Americans, and their supporters both free black and white.

References:

John Cunningham, Newark.

Newark Academy, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees,” 1792.

Clement Price, Freedom Not Far Distant.

Giles R. Wright, Afro-Americans in New Jersey: A Short History.

Bills of Sale, Courtesy of the New Jersey Historical Society.

Advertisement in The Centinel of Freedom in 1802, offering a reward for the return of an enslaved man named “Will” who escaped from the estate of David Banks. The man was last seen in Lime, CT and Providence, RI. — Credit: New Jersey Historical Society

Explore The Archives

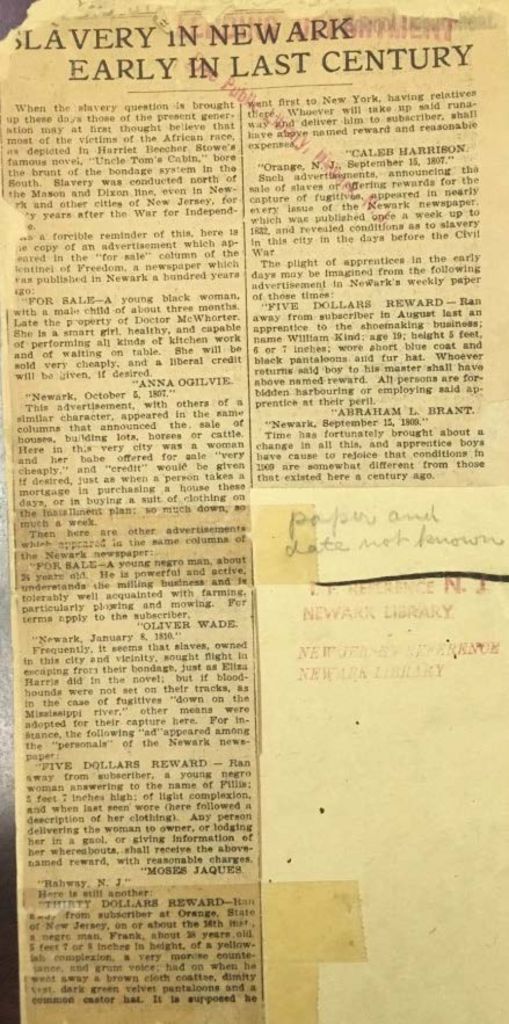

An unmarked newspaper article detailng, in brief, the history of slavery in Newark through advertisements for the sale of enslaved people, or reward for the return of runaways, in the city. Newspapers, such as The Centinel of Freedom, carried such advertisements in Newark. — Credit: Newark Public Library

The front page of The Sentinel of Freedom in 1802. This newspaper and others would routinely post advertisements for the sale of enslaved African Americans and rewards for the return of runaways. — Credit: New Jersey Historical Society

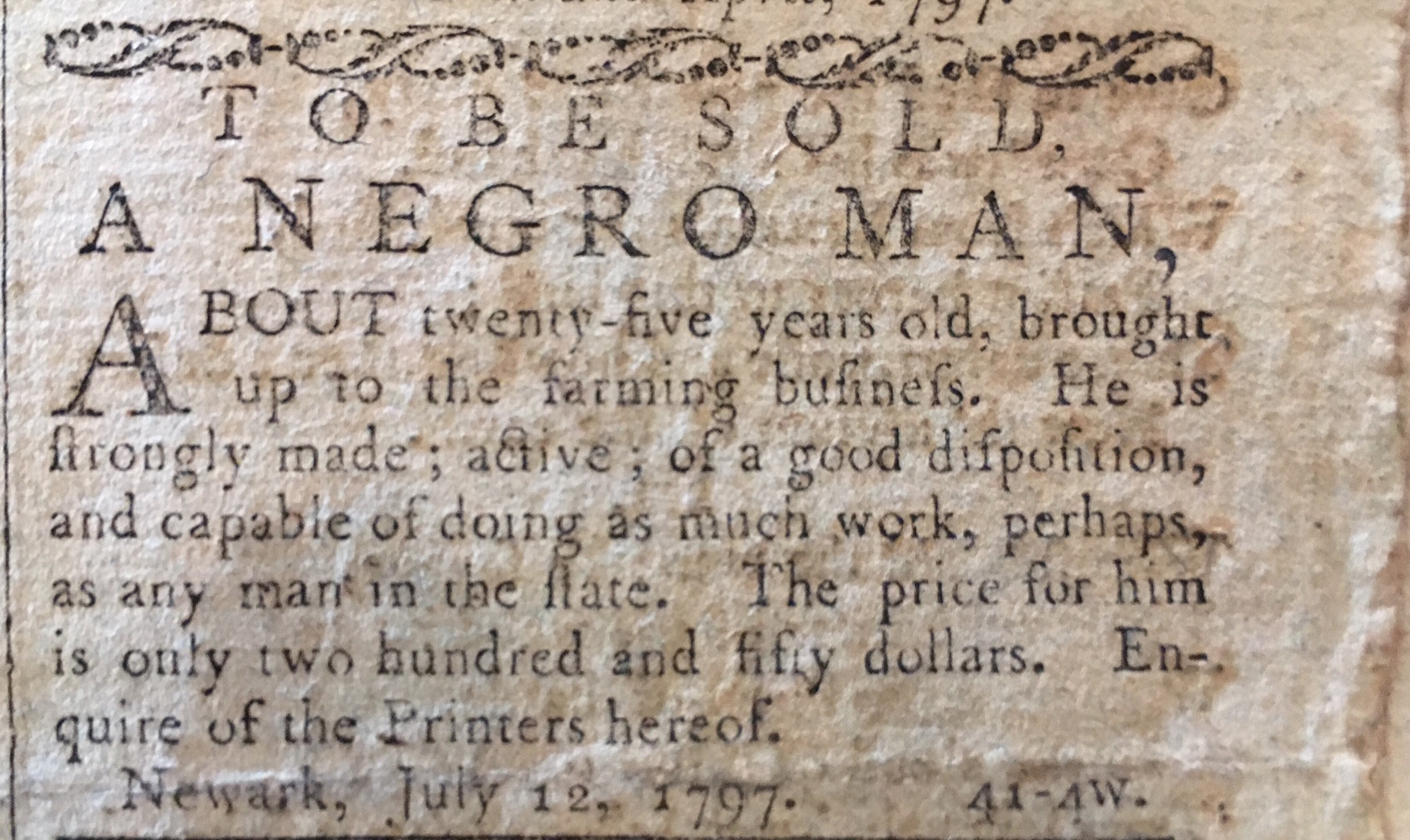

Advertisement in The Centinel of Freedom in 1797 for the sale of an enslaved 25-year-old man in Newark. — Credit: New Jersey Historical Society

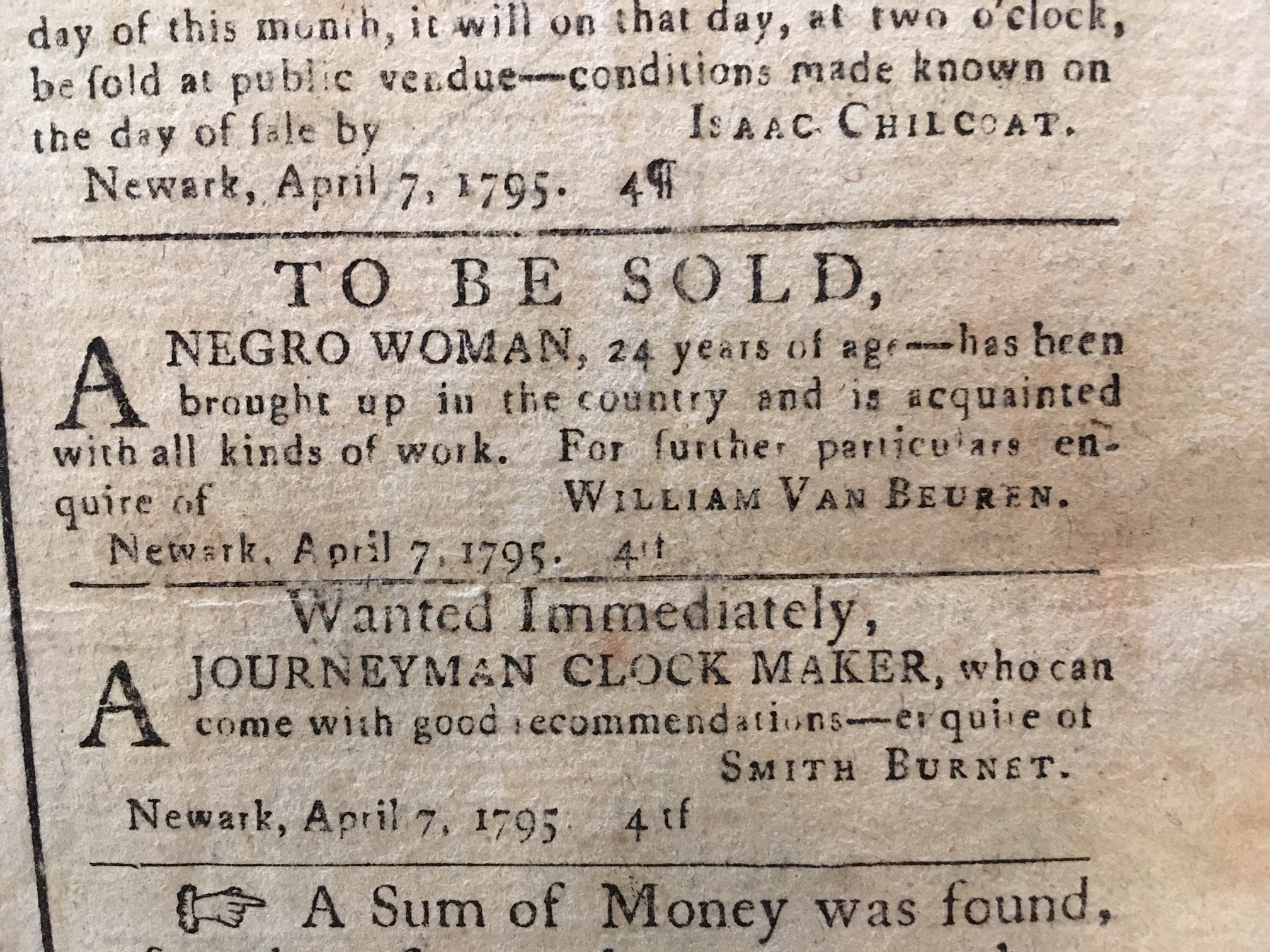

Advertisement in The Centinel of Freedom in 1795 for the sale of an enslaved 24-year-old woman in Newark. The person selling this woman was William Van Beuren. — Credit: New Jersey Historical Society

Advertisement in The Centinel of Freedom in 1797, offering a reward for the return of two enslaved men named, John Burk and Moses Bryant, who escaped from the estate of Luther Goble. — Credit: New Jersey Historical Society

Advertisement in The Centinel of Freedom in 1802, offering a reward for the return of an enslaved man named Bill and his wife Hannah, who escaped from the estate of Nathaniel Seabury. — Credit: New Jersey Historical Society

Advertisement in The Centinel of Freedom in 1800, offering a reward for the return of an enslaved man named Rob, who escaped from the estate of David Nichols. — Credit: New Jersey Historical Society

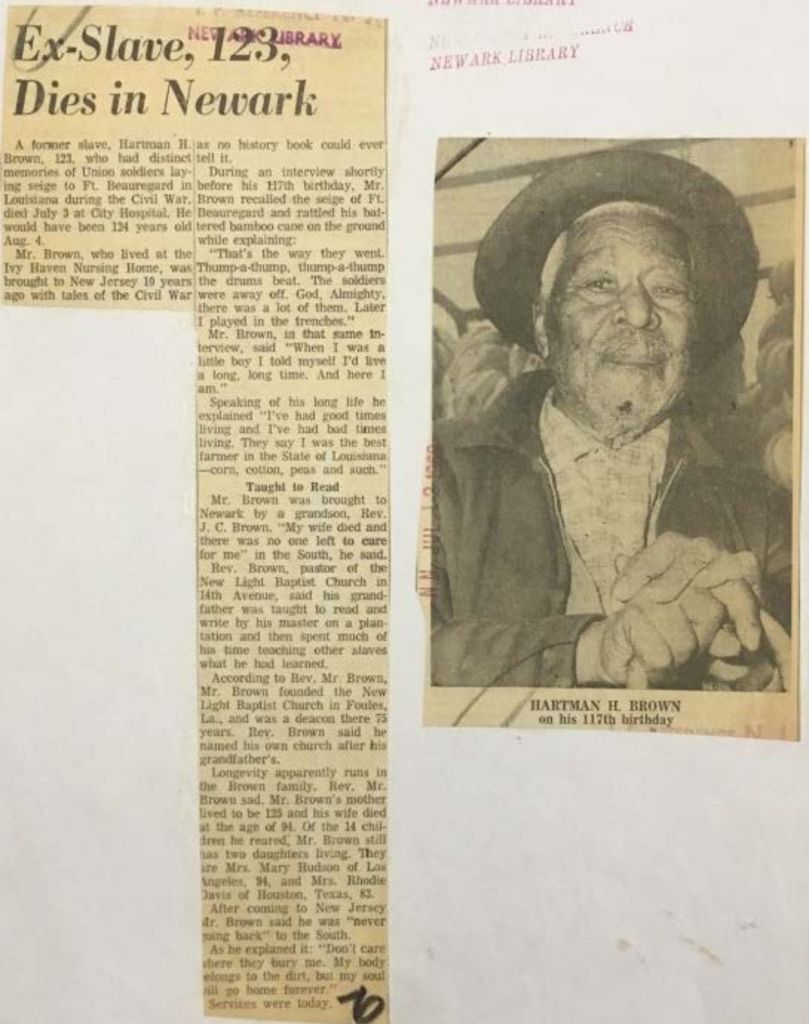

An undated article from the Newark Evening News on the life and death of Hartman H. Brown, who was enslaved in Louisiana and later moved to Newark. Mr. Brown’s grandson, Rev. J.C. Brown, was the pastor of the New Light Baptist Church on 14th Avenue in Newark. — Credit: Newark Public Library