Albert Mersier, Jr.

Albert Mersier, Jr.’s parents, Albert Sr. and Mrs. Gussie Mersier, had moved to Newark from Lincolnton, Georgia thirty years before the rebellion. Mr. Mersier, Sr. had managed to purchase two bars in the city, the Cozy Corner and the Babalu Club, after years of hard work. During this time, the Mersier’s had five children—four daughters and a son, Albert, Jr., who graduated from East Side High School in 1965. Instead of eventually inheriting his father’s businesses, the 20-year-old Albert Jr. was fatally shot by Newark Police just before midnight Friday, July 14th—down the street from the Babalu Club.

Journalist and author Ron Porambo followed the case…

“The scene of Mersier’s death was far from the riot area. He died because police behavior was becoming uglier and uglier as the riot persisted. Mersier was sentenced to death for a petty crime, as were other victims, and he was executed on the spot.

The youth, over six feet tall and heavyset, managed to squeeze through a 14-by-20 inch opening in a sliding door after he and a companion had kicked in the panel. Nothing inside W.W. Grainger, an electric motor company, was worth shooting a man over.

‘When someone’s running from you,’ his father said, ‘you know damn well they’re afraid of you. I want to know why they had to kill him.’ A year later, Albert Mersier, Sr.—a gravel-voiced man who smoked three packs a day—was still grieved enough to retrace the steps again, as he had done many times before in his mind.

From the truck platform door the younger Mersier had run some twenty yards to reach the street, another fifteen to cross it and then down Mulberry Street’s sidewalk some twenty-eight more yards where he was overtaken by a .38 caliber bullet that kept on going after it killed him. ‘That’s my belief on the right hand of God,’ his father said. ‘They just killed him because they wanted to kill him. A month after the riot two cops came into my bar trying to sell stolen television sets—stolen! He wasn’t doing no God damn other than what they were doing but nobody shot them.”

Albert Mersier, Jr. was dead at the age of 20 after having been shot in the back by Newark Police officers, who fired seven to eight shots at the young man for stealing from a warehouse. As witness John Patrick White testified, “The police were shooting as we ran…I went back and saw Albert laying on the ground, face down. He was dead.”

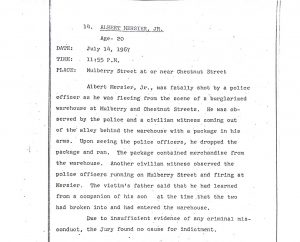

The Essex County Grand Jury found “no cause for indictment” of the officers involved.

References:

Ronald Porambo, No Cause for Indictment: An Autopsy of Newark

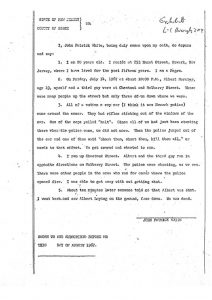

Witness Testimony of John Patrick White before the Essex County Grand Jury

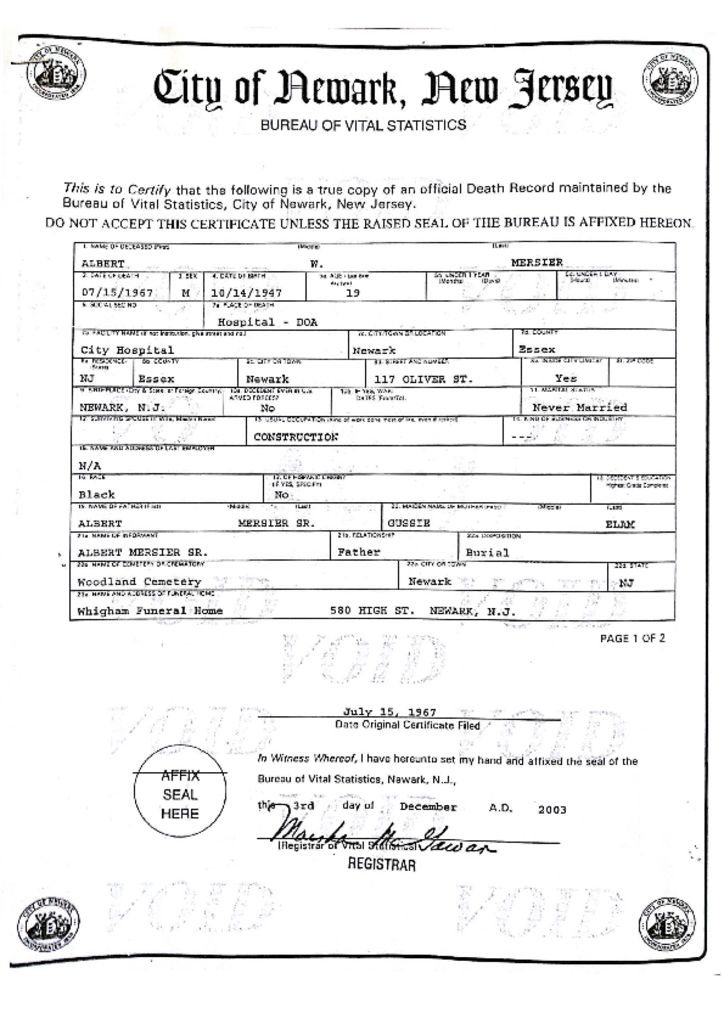

Copy of the Death Certificate for Albert Mersier, Jr., issued by the City Of Newark’s Bureau of Vital Statistics. — Credit: Newark Public Library

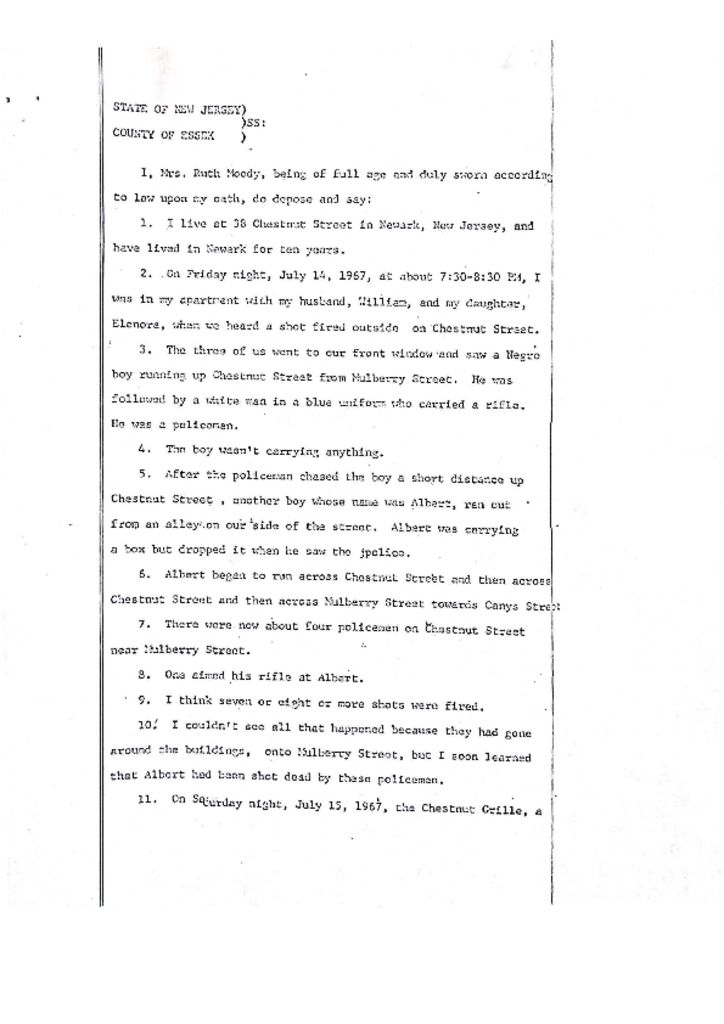

Deposition of Mrs. Ruth Moody, in which she describes witnessing the shooting of Albert Mersier, Jr. by police officers. — Credit: Newark Public Library