Urban Renewal and Detroit’s Black Community

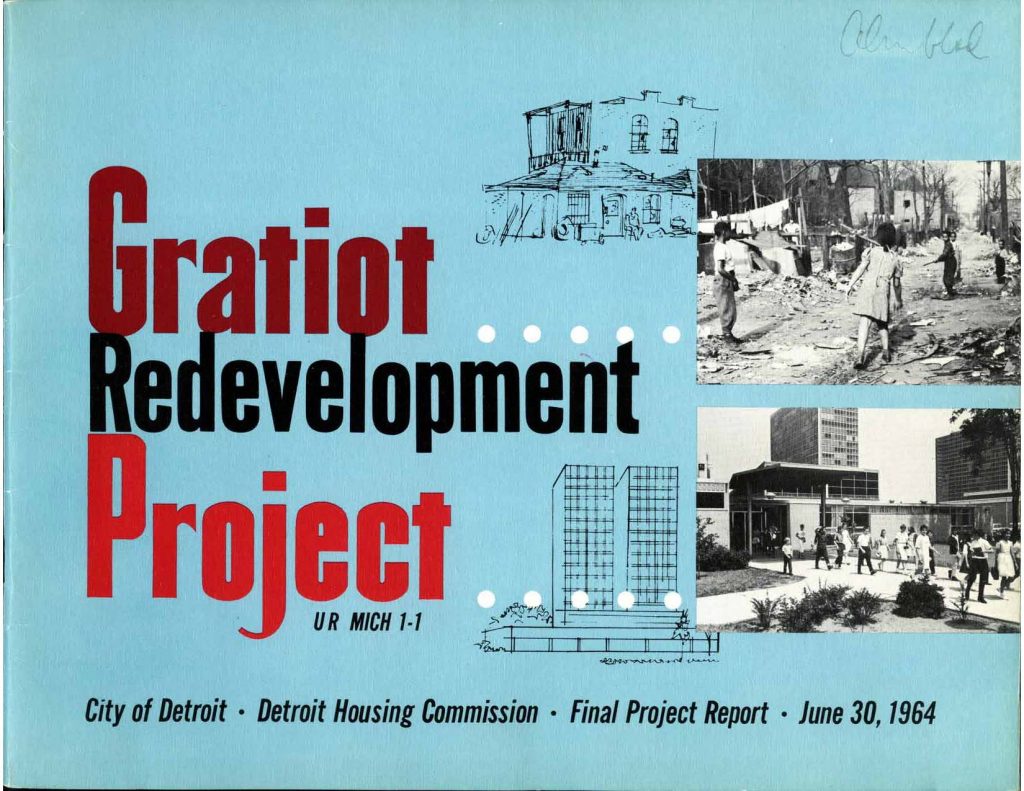

In response to the conditions of inner-city areas like Black Bottom, Congress passed the 1949 Federal Housing Act to stop the spread of “slums” and to help cities clear “blighted” areas. This new federal act laid the basis for a program known as “Urban Renewal,” designed for slum clearance and middle-class housing development.

Within a year of the passage of the Federal Housing Act, it became clear to many black residents of Detroit that “Urban Renewal” really meant “Negro Removal.” To make way for middle-income housing, which few Black residents could afford, historic Black neighborhoods in Detroit were systematically demolished. Among the first neighborhoods to be demolished was that of future Mayor Coleman Young’s, where his father’s tailor shop was destroyed in 1950.

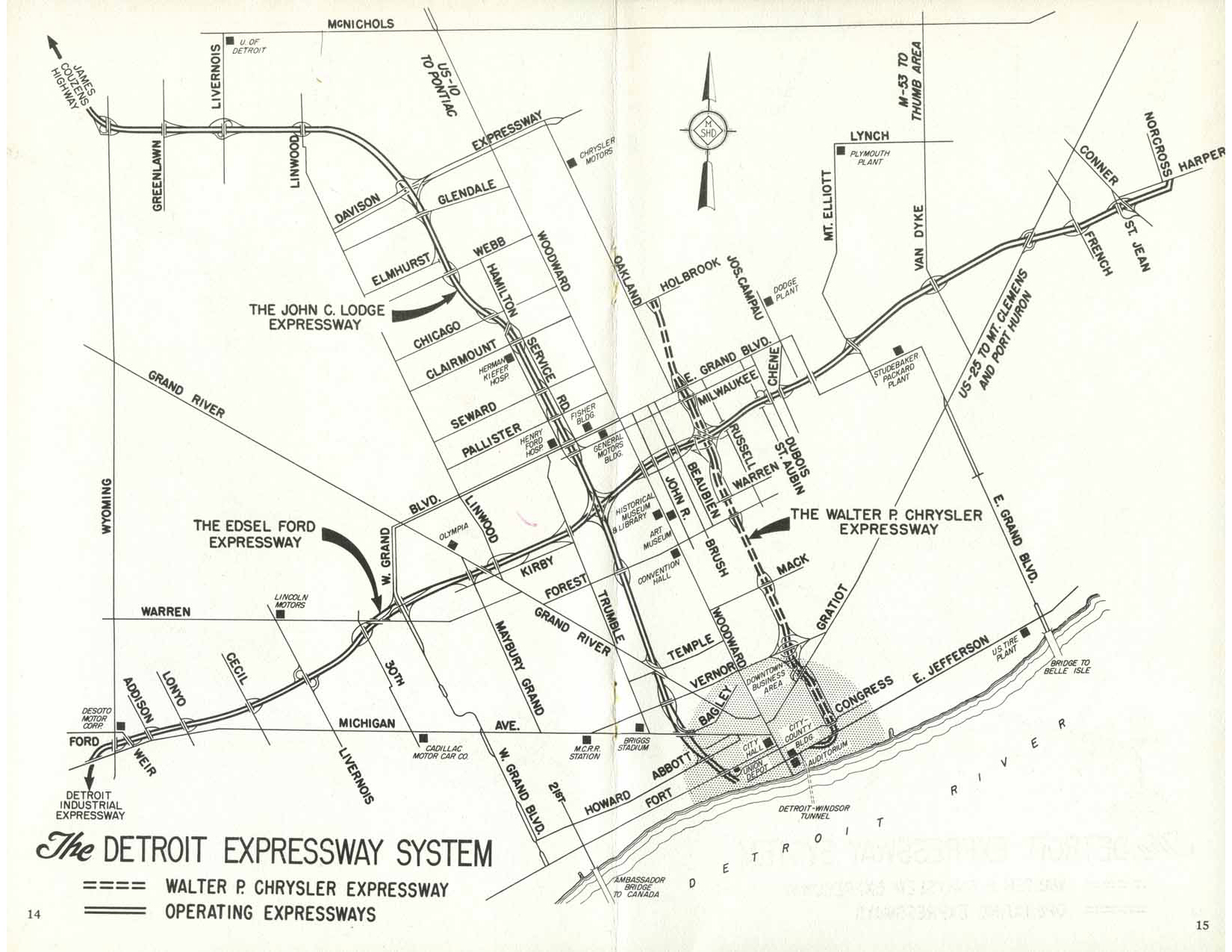

On top of the urban renewal program, highways were also being constructed right through Black neighborhoods throughout the 1950s-60s. To aid in this white exodus promoted by the FHA, highways were built in the heart of Black communities in Detroit, Newark, and dozens of other cities, displacing thousands of residents, destroying and destabilizing black communities, and weakening black political power.

The very neighborhoods which local, state, and federal governments were actively targeting and destroying for new highway and residential construction had fostered the development of nationally significant religious, cultural, and political institutions: the Nation of Islam had been established there; it was once “the largest concentration of Black-owned businesses in the country; and the area’s religious and cultural institutions had given birth to the “Motown Sound.” In 1960, the Chrysler Freeway was built through Hastings Street, destroying Rev. C.L. Franklin’s New Bethel Baptist Church. According to his daughter, Aretha, a predominantly white Catholic Church one block away was spared. In 1964, the historic Gotham Hotel was also demolished.

By 1963, urban renewal developments had wreaked havoc upon housing for Detroit’s poor and working class Black community and made the city’s housing crisis even worse. Between 1960 and 1967, over 25,000 housing units were destroyed, while only 15,000 were built. Furthermore, the vast majority of these newly constructed units were designed for tenants with middle to upper class incomes. Because the city had lost 140,000 manufacturing jobs (most unskilled and semiskilled) that had provided economic opportunities for Black laborers, few African Americans could afford these new developments.

With a vacancy rate of only 1%, the lowest in the nation alongside Newark NJ, black tenants who had their homes destroyed were pushed into the “inner city” and “middle city” areas, with little choice except to pay overpriced rent for units in rapidly dilapidating buildings. Slumlords capitalized on the housing shortage by jacking up rents and reducing services and maintenance with very little consequences from the city. By 1966, only 1,000 of 27,000 residences in the “inner city,” and 39% of those on the “middle city” were considered to be in “sound condition.” The Urban League of Detroit projected that by 1967 the city would have a shortage of nearly 20,000 affordable units.

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident Helen Kelly, in which she describes the impacts that urban renewal and highway construction had on the city’s Black community.–Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

A street view of retail stores along Hastings Street at the intersection of Mack Ave. This neighborhood was later destroyed to build the Detroit Medical Center.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

A map of the Detroit expressway system as featured in the souvenir pamphlet presented to attendees of the ground breaking ceremony for the Walter P. Chrysler Expressway (1959).–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Explore The Archives

A view of the Chrysler Freeway construction project in Detroit, looking east from the roof of the City-County Building (undated).–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Final report of the Gratiot Redevelopment Project, an urban renewal program that cleared 129 acres of land, including the Black Bottom and Paradise Valley areas. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

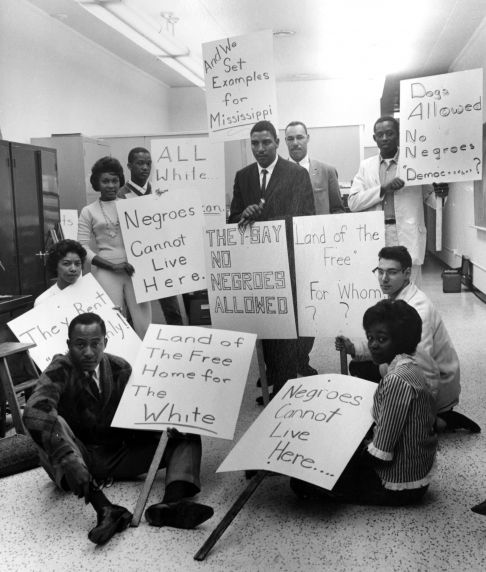

The Community Response

These decades of housing discrimination and the housing crisis that urban renewal created in Detroit “galvanized Black anger and activism” in the city in the 1960s. After focusing primarily on open housing campaigns in the late 1950s-early 1960s, by 1964 the city’s chapter of the NAACP, along with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), began targeting slumlords and the inhumane housing conditions faced by large swaths of Black Detroit residents. That year, CORE responded to growing grassroots demands for housing and economic justice by relocating its office to Twelfth Street to focus on “problems of poverty” as a catalyst for organizing “mass action” in the city.

In 1964-65, the Detroit NAACP and CORE began to organize tenants’ rights organizations, and coordinated numerous protests, marches, and rent strikes. Rent strikes worked by organizing tenants to withhold rent payments to force landlords to make repairs to apartment units. Tenants would collectively deposit their rent payments into an escrow account, and landlords could collect the back rent once repairs were completed. During a series of rent strikes against notorious slumlords, the Goodman Brothers, CORE even organized pickets outside of Goodman’s suburban home to show his neighbors how he treated his tenants.

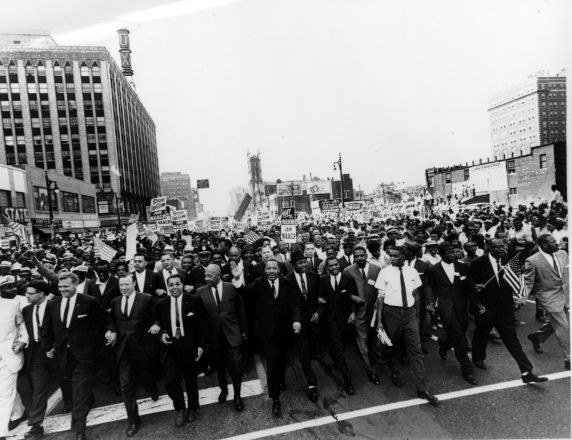

More radical activists in the city were also becoming involved in struggles against urban renewal and slum housing conditions. By 1965, Rev. Albert Cleage, James and Grace Lee Boggs, the Northern Student Movement, and the Socialist Workers Party were taking part in housing demonstrations and organizing people to stand up for their rights. National civil rights leaders were also paying attention, drawing Martin Luther King, Jr. and CORE executive director James Farmer to the city to take part in marches and demonstrations.

During a visit to the city in May of 1965, Farmer predicted that tenants’ rights activists in Detroit would be at the forefront of a “long hot summer.” To many in the city’s African American community, however, the housing crisis was part of a larger problem. Black residents of Detroit had been excluded from the economic, social, and political power structures that were controlling the city and destroying their neighborhoods. By the mid-1960s, it was clear that African American communities in Detroit were on the move for self-determination and economic and political empowerment.

Members of the NAACP picket the apartment building at 4762 Second Street for discriminative housing practices. At right is Jackson (Jackie) Vaughn, III. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 1989 interview with Ed Vaughn, in which he discusses urban renewal and highway construction in Detroit, and community resistance in the 1960s.–Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Explore The Archives

Members of the NAACP’s Housing Committee create signs in the offices of the Detroit Branch in 1962 for use in a future demonstration. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. leads an estimated crowd of 125,000 civil rights activists down Woodward Avenue in downtown Detroit during the historic “Walk to Freedom.” Rev. C.L. Franklin, Walter Reuther, Rev. Albert Cleage and Mayor Jerome Cavanagh are all in view.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University