Suburbanization and Segregation in Detroit

The Federal Government, local politicians and private interest groups all played a part in decisions about land use that shaped the character and culture of the black community in Detroit. During the Great Depression when the nation’s economy was crippled, the federal government established the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) to boost the slumping housing industry. The FHA insured low-interest loans to stimulate housing construction, subsidize homeownership, and put people back to work to boost the national economy.

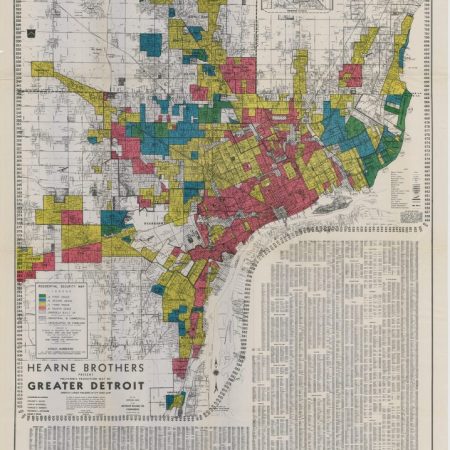

As construction and homeownership boomed, however, African Americans were largely excluded from the huge benefits the FHA provided to white Americans. The FHA adopted policies that prevented African Americans from securing loans to buy homes. In its Underwriting Manual, the FHA declared that black neighborhoods were undesirable investments and endorsed the practice of “redlining” to restrict loans to white communities. Redlining was a policy of ranking the credit-worthiness of potential buyers based on the racial composition of the neighborhood they lived in. Real estate agencies and loan agencies would draw red lines around African American neighborhoods on maps and discourage banks from offering loans within the lines. With these practices, the FHA and federal government played a lead role in segregating northern cities, and stimulated the development of racially-restrictive suburban communities.

White people were encouraged to seek single-family home ownership in newly constructed suburban communities outside Detroit. The FHA insured construction of these all-white areas, such as Taylor, Livonia, and Warren, while black people were largely confined to inner-city areas that were redlined, and drained of their tax base.

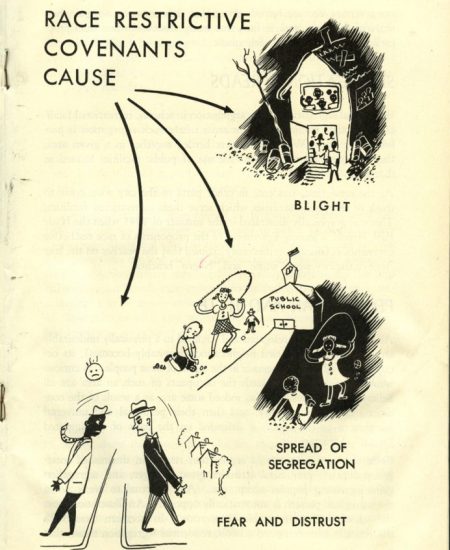

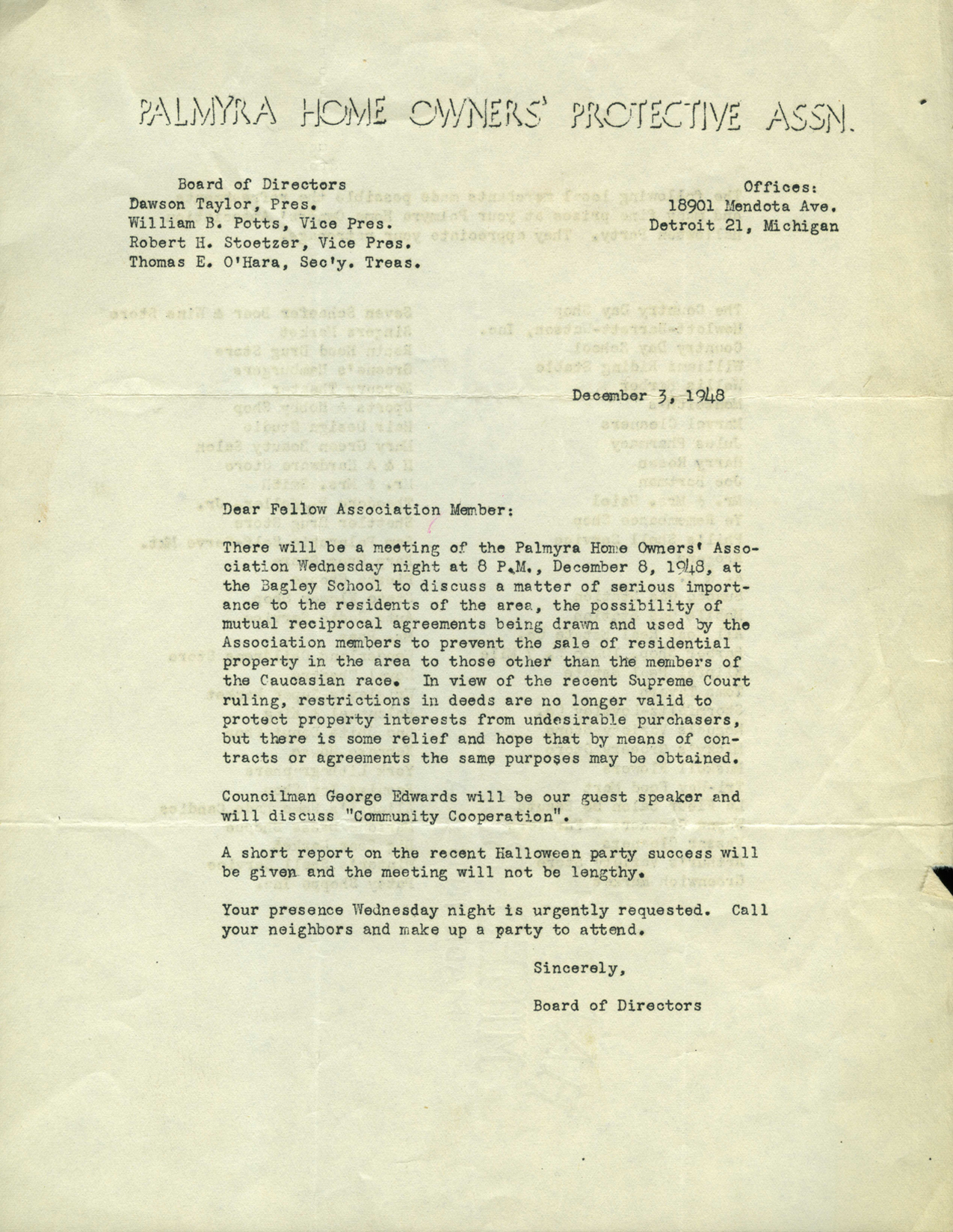

In addition to preventing access to loans, white communities adopted “restrictive covenants” to keep African Americans from moving into their neighborhoods. From 1945-1965, roughly 200 white neighborhood associations were formed, according to historian Thomas Sugrue, “most with the explicit purpose of keeping Blacks away.” Groups like the Palmyra Home Owners’ Protective Association drew up legal agreements called “restrictive covenants” which forbid members from selling or renting to non-white families. In many cases, these covenants were written into the deeds of houses and enforced both legally and physically.

This map of Detroit from 1939 shows the credit rating assigned to various neighborhoods in the city. The neighborhoods in red were predominantly African American.–Credit: www.detroitography.com

A graphic depicts the consequences of property covenants restricting where Black residents may live.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Explore The Archives

Clip from a 1989 interview with Eleanor Josaitis, co-founder of Focus: HOPE, in which she discusses suburbanization and the Civil Rights Movement in Detroit.–Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

The Palmyra Home Owners’ Protective Association Board of Directors announces a meeting to discuss ways to prevent minorities from purchasing homes in their neighborhood. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

The Black Response to Racism: “Let’s Build Our Own!”

Excluded from the benefits of government housing programs and from many of the City’s jobs, Detroit’s African American residents built their own communities and institutions. Neighborhoods like the Black Bottom and Paradise Valley districts, where many African Americans settled during the Great Migrations, became hubs of Black businesses, churches, organizations, and nightlife. “Black entrepreneurship really was flourishing back in those days,” Horace Sheffield remembered, “Blacks here had the highest per capita earnings by being in the auto industry, and…up and down Milford Avenue, we had all kinds of black business, hawkers, drug stores.”

Despite the presence of Black-owned businesses and a well-established community, economic inequality and residential segregation caused serious problems. Black Bottom was terribly overcrowded and residents paid higher rents for inferior housing units. Although jobs were available to some in the auto industry, the general lack of employment opportunities and residential segregation left most residents with no place else to go.

Detroit native Horace Sheffield describes growing up in the African American community on the West Side of Detroit in the 1920s-1930s.–Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Explore The Archives

Detroit resident Shelton Tappes describes the neighborhood he grew up in during the 1920s-1930s before it was destroyed by highway construction in the 1950s.–Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

In this historical photo, neighbors enjoy their front porches on May 8, 1950 located at 1981 Mullett St. in Black Bottom, an area that was torn down in the 1950s to make way for the Chrysler Freeway and the Detroit Medical Center. Black Bottom is the ancestral neighborhood of many metro Detroit African-Americans. –Credit: Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library