Phil Hutchings

A native of Cleveland, Ohio, Hutchings was a member of the NAACP Youth Council growing up before attending Howard University in Washington, D.C. At Howard, Hutchings was a member of the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG), whose membership included other notable figures in the Civil Rights Movement, such as Stokely Carmichael, Courtland Cox, and Ed Brown. In 1964, Hutchings and other NAG members travelled to Mississippi to work with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) in their voting campaign to challenge the white-only primary for the 1964 presidential election.

After returning to Washington, D.C. from Mississippi and then Cambridge, Maryland, Hutchings found himself in Newark in December of 1964, having been recruited by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) member Tom Hayden. ‘Tom was shameless,’ Hutchings recalled. ‘He got me to come to a party in New York City, and after I had a few drinks, he told me how important Newark was, and why I ought to be there. To me, after the civil rights stage, [the power structure] was going to create Birminghams all over America, where everybody could sit on the bus wherever they wanted, eat at any restaurant, and the problem of racism would become less obvious. But we still have all those other problems related to class. Newark’s majority black population and its size made this a place to find some of the answers for the problems of race and class.’

As a member of the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP), Hutchings organized around principles of self-determination for the city’s Black communities in the fields of housing, policing, and education. To Hutchings, organizing in Newark was not just about improving conditions in housing, education, policing, etc., but to establish Black institutions and Black Power in the city.

Hutchings was also a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and was responsible for SNCC Chairman, Stokely Carmichael, coming to Newark in 1966. Carmichael’s visit to Newark marked a shift in Hutchings’ political consciousness in Newark away from interracial organizing and toward Black Power, which provided a more realistic approach to organizing in the predominantly Black Central Ward.

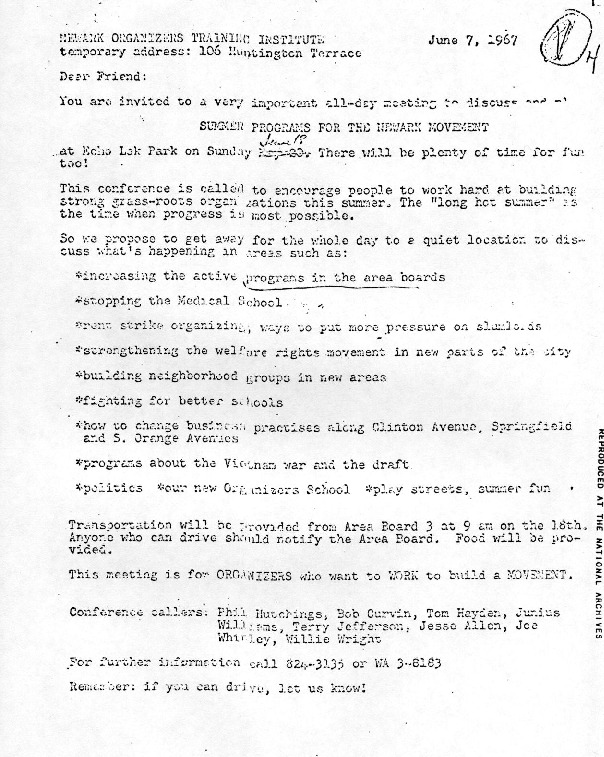

Hutchings and others attempted to bring Black Power into the political arena in Newark in 1966 by supporting the first, unsuccessful campaign of eventual Mayor Ken Gibson. In 1967, Hutchings was beaten by Newark Police during the rebellion in July and helped to organize the National Conference on Black Power, which took place just days after the rebellion had been suppressed. He was also a founding member, along with Junius Williams, of the Newark Area Planning Association (NAPA), which was instrumental in the fight against the New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry urban renewal plan. In 1968, Hutchings succeeded H. Rap Brown as the national chairman of SNCC.

“What’s interesting in terms of the Newark experience looking back on it is…we had some real power,” Phil Hutchings later reflected. “And nothing I’ve worked with in the same way since has had that type of grassroots base where the mayor and city council were very concerned…of what we were going to do.”

References:

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

Interview with Phil Hutchings, conducted by Joseph Mosnier in Oakland, California on September 11, 2011, for the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Library of Congress.

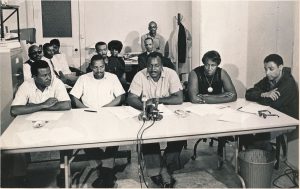

Phil Hutchings discusses how Black political nationalism was defined in Newark and its implications for interracial organizing. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Invitation to participate in the Newark Organizers Training Institute in June, 1967. Hutchings was one of the organizers of the institute. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

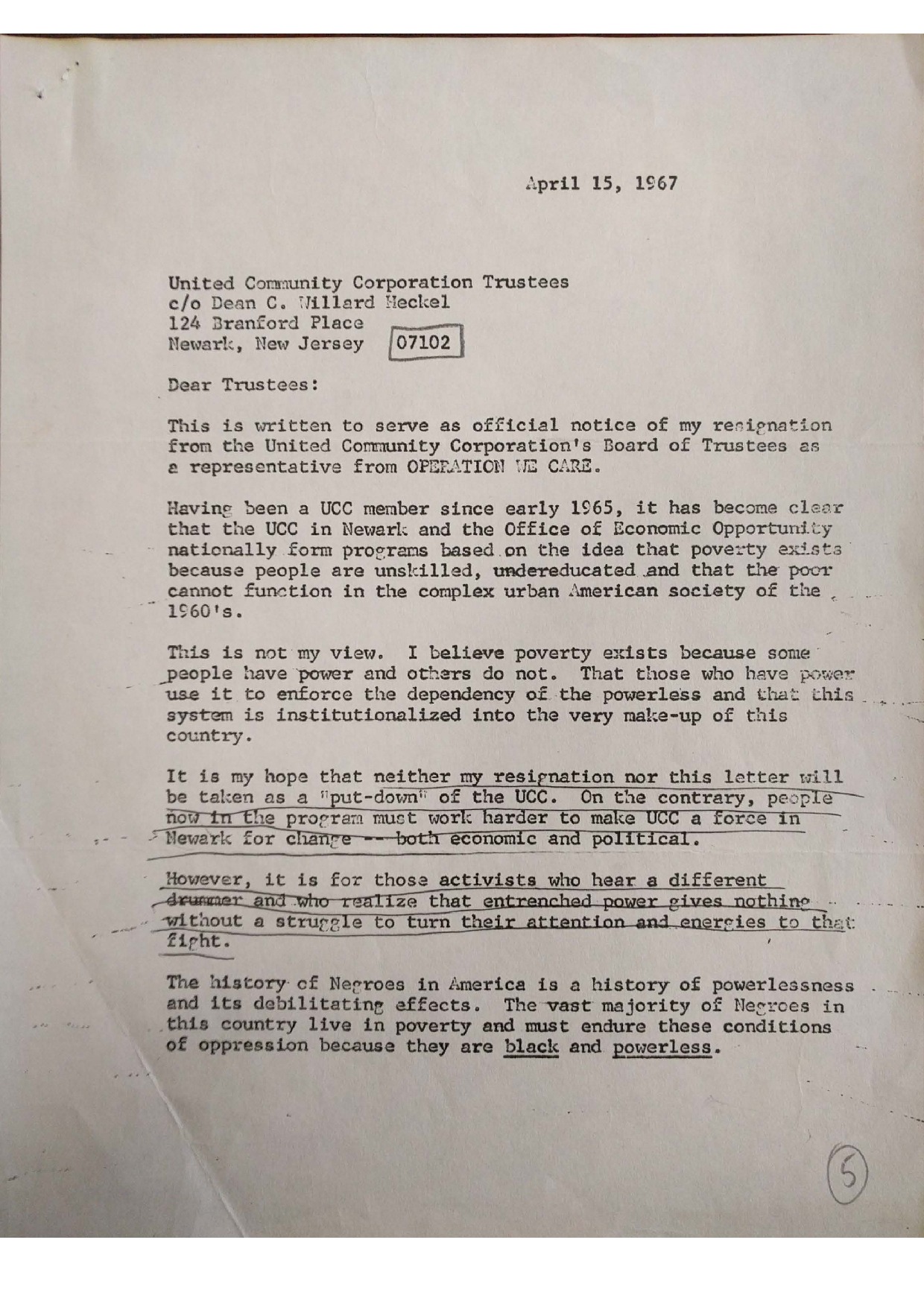

Letter of resignation from Phil Hutchings to the United Community Corporation in April, 1967. — Credit: Newark Public Library