Jesse Allen

Jesse Allen was born in Florida before making his way North to Newark, and had a history as a labor union activist. When the “students” came to Newark with Tom Hayden and others from the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), they met Jesse living in the Lower Clinton Hill section of the city. He was one of the first residents recruited to organize with the newly created Newark Community Union Project (NCUP).

He became one of the most effective organizers in NCUP. His laid back style of organizing was characterized by his ability to use his southern accent and “down home” ways to get people in the neighborhood to trust him. He was a great listener. He specialized in getting people to go on rent strike, to get the landlords to fix up the buildings. Jesse was one of the people, and they responded to his invitation to join NCUP, and participate in their confrontational actions.

Jesse’s showcased his speaking skills at a 1965 SDS conference in Cleveland, during which he “stopped in the middle [of his speech] and asked Fannie Lou Hamer to come up and lead the singing of ‘Go Tell It on the Mountain,’ which…really got people very enthusiastic, and then went back to the speech.”

Jesse supported NCUP’s move to take over Area Board #3 of the United Community Corporation by (UCC), Newark’s War on Poverty Program in 1965. (Jesse’s signature words were his convoluted Florida accent of the word “Area,” an expression that defies written correspondence). Jesse and other NCUP members were responsible for getting the people to the meeting and managing the floor debates on many issues.

Jesse was one of the first people hired by the Area Board, proving to NCUP members that they could receive some of the benefits of the hard fought battles. But Jesse was no longer in people’s houses but at the PAG office. There were new titles and less of a sense of a neighborhood.

Jesse Allen was one of the leaders developed in the NCUP experience who outlasted the organization’s lifetime. In 1974, he was elected to the position of Central Ward Councilman. Once he was elected, however, some of his flair as an organizer was lost as he scrambled to keep up with the culture of elected office.

References:

Recollections of Junius Williams

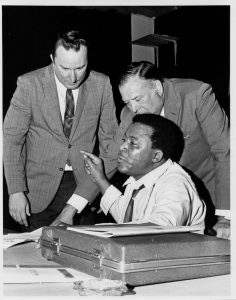

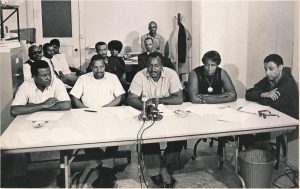

Jesse Allen addresses a group at “The Newark Conference” organized by NCUP in 1965. — Credit: Robert Machover

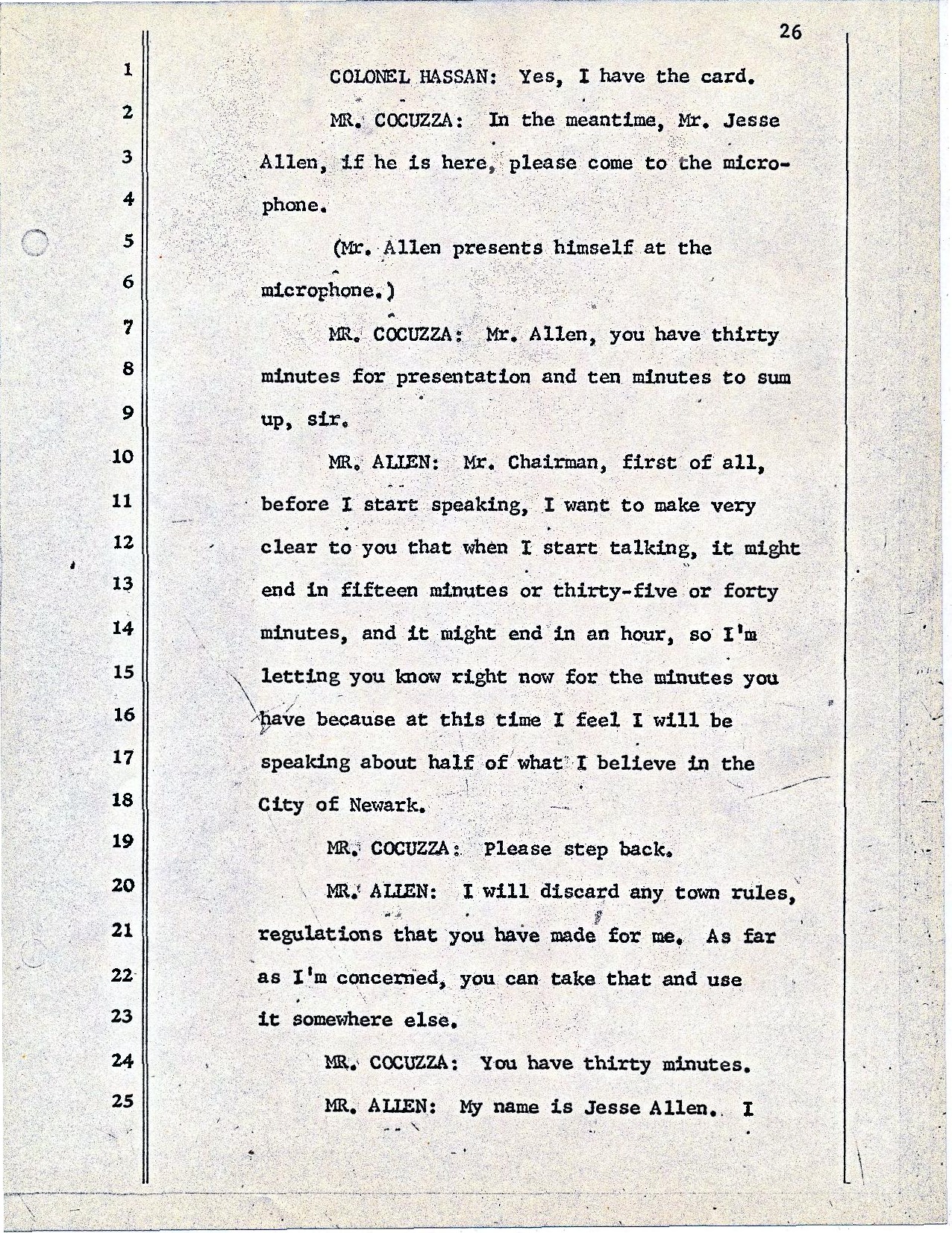

Transcript of Jesse Allen’s statement to the Central Planning Board on June 13, 1967 during the Medical School “blight hearings.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

UCC member Edna Thomas reflects upon Jesse Allen and the Newark Community Union Project. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries