James Walker

Newark Police captain James Kinney told the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1968, that “prior to the riots in Newark, James Walker was observed by police in the forefront of practically every demonstration against constituted authority.” Though Kinney was known to embellish information in these hearings, Walker was certainly an active presence in struggles for civil rights in Newark.

James Walker was born September 3, 1918 in New Haven, Connecticut. Walker moved to Newark in the late 1940s after serving in the US Army during World War II and took up residence in the city’s South Ward. He was also a baseball player in the Negro League, perhaps playing with the Newark Eagles.

He first became involved in these struggles through an organization called ANVIL, a “social work, civil rights, political, and business organization” that advocated for employment opportunities, job training, business ownership, social welfare, and police reform to benefit Newark’s Black communities.

While working as a factory worker in the city, Walker got involved with the United Community Corporation (UCC), Newark’s War on Poverty agency which launched in 1965. The UCC’s structure was designed to empower local people to become leaders in the organization and their communities. “After we got involved in the War on Poverty,” Walker recalled, “we had something else…We became involved in the things happening in our communities.” Walker quickly became a personnel director in the UCC and eventually assistant director for Total Employment and Manpower (TEAM).

After becoming involved in the UCC, Walker became active in many community struggles outside of the organization. When the New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry was proposed to be built on 180-acres of “urban renewal” land in the Central Ward, Walker was a regular fixture at the “blight hearings” that were held in the summer of 1967. Speaking at a hearing on June 13th, Walker told the Central Planning Board, “We are not fighting for civil rights. We are here fighting for human rights, and frankly gentlemen I don’t think that you have one ounce of decency within your bones, because you cannot conceive of human rights.”

When the Newark rebellions broke out in July 1967, as James Walker and many others predicted in their speeches at the “blight hearings,” Walker took an active leadership role on the streets. Outside of the Fourth Precinct, where cabdriver John Smith was arrested and beaten, Walker was one of several leaders who demanded to see Smith to check on his health. Walker also took part in meetings with other community leaders and city officials during those five days to offer suggestions and issue demands.

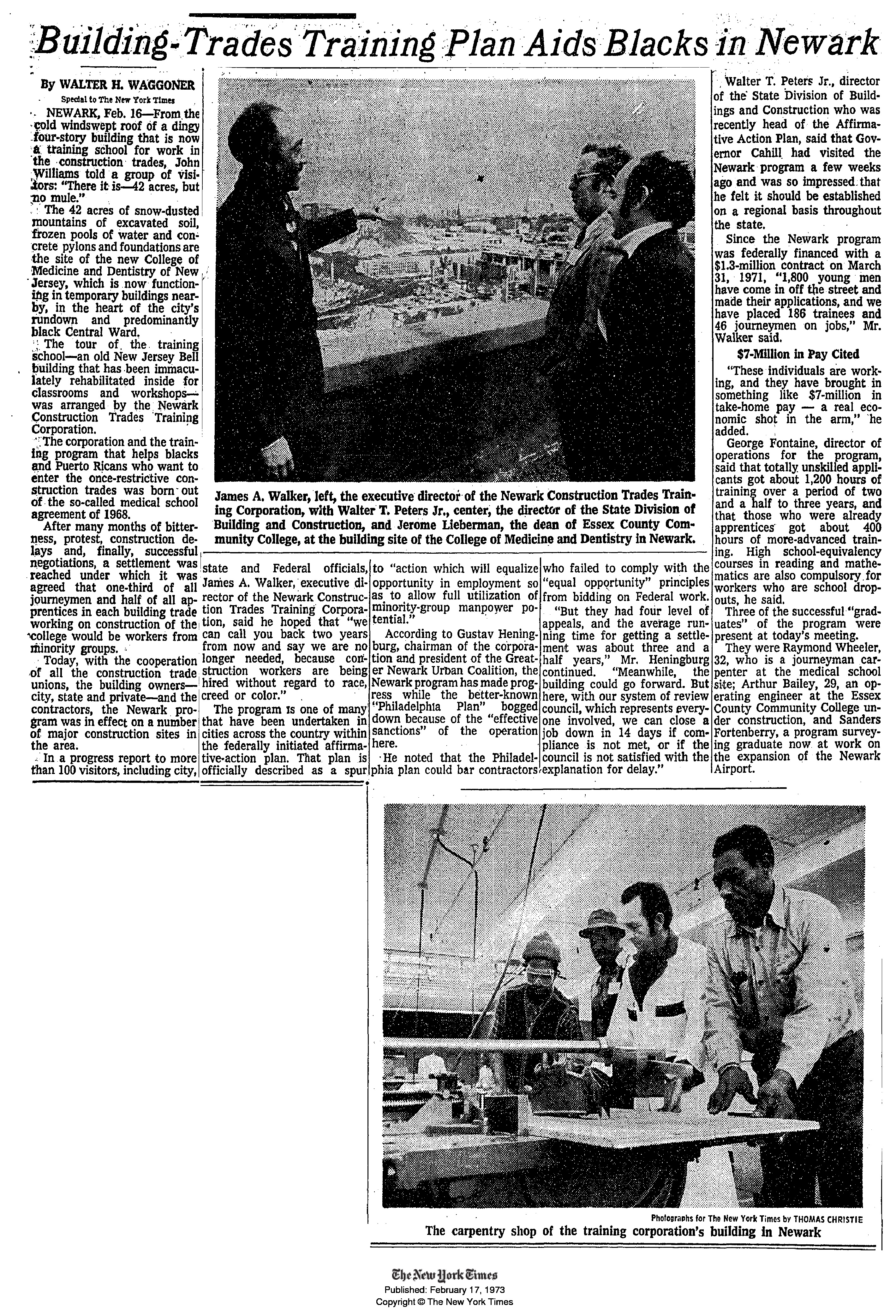

When the Medical School Agreement was reached after the rebellion, Walker and George Fontaine served as chief executives of the Newark Construction Trades Training Council (NCTTC). The NCTTC was a nonprofit organization that trained hundreds of Black and Latino men for jobs in the construction industry, saw to their placement on public construction jobs, and fought with the construction unions to grant them union membership– beginning with the construction of the Medical School.

References:

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

James Walker explains how participation in the UCC translated into economic and political empowerment. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Transcript of James Walker’s statement to the Central Planning Board on June 13, 1967 during the Medical School “blight hearings.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

Article from The New York Times on the NCTTC, featuring a photo of James Walker. Walker was an executive director of the organization. — Credit: The New York Times