Hilda Hidalgo

Hilda Hidalgo was born in Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico and graduated from the University of Puerto Rico before coming to the United States to continue her education at Catholic University in Washington, D.C. Before making her way to Washington, however, Hidalgo spent time with a friend in Texas to work on improving her English. “It was in Texas,” Hidalgo later recalled, “that I first was refused service in a restaurant and it was the first time I confronted American racism. It was a totally new experience, but it was a traumatic experience for me. And I realized then, at that point, that I had to do something to really address that issue.”

After earning her Master’s Degree at Catholic University, Hidalgo came to Newark at the age of 32 to begin a career as District Director of the Girl Scout Council of Greater Essex, a position she maintained for five years. During this time, Hidalgo also organized tenants in the city’s public housing projects, specifically the Hayes Homes. She also worked with Americans for Democratic Action, and was involved with George Richardson’s independent political campaigns.

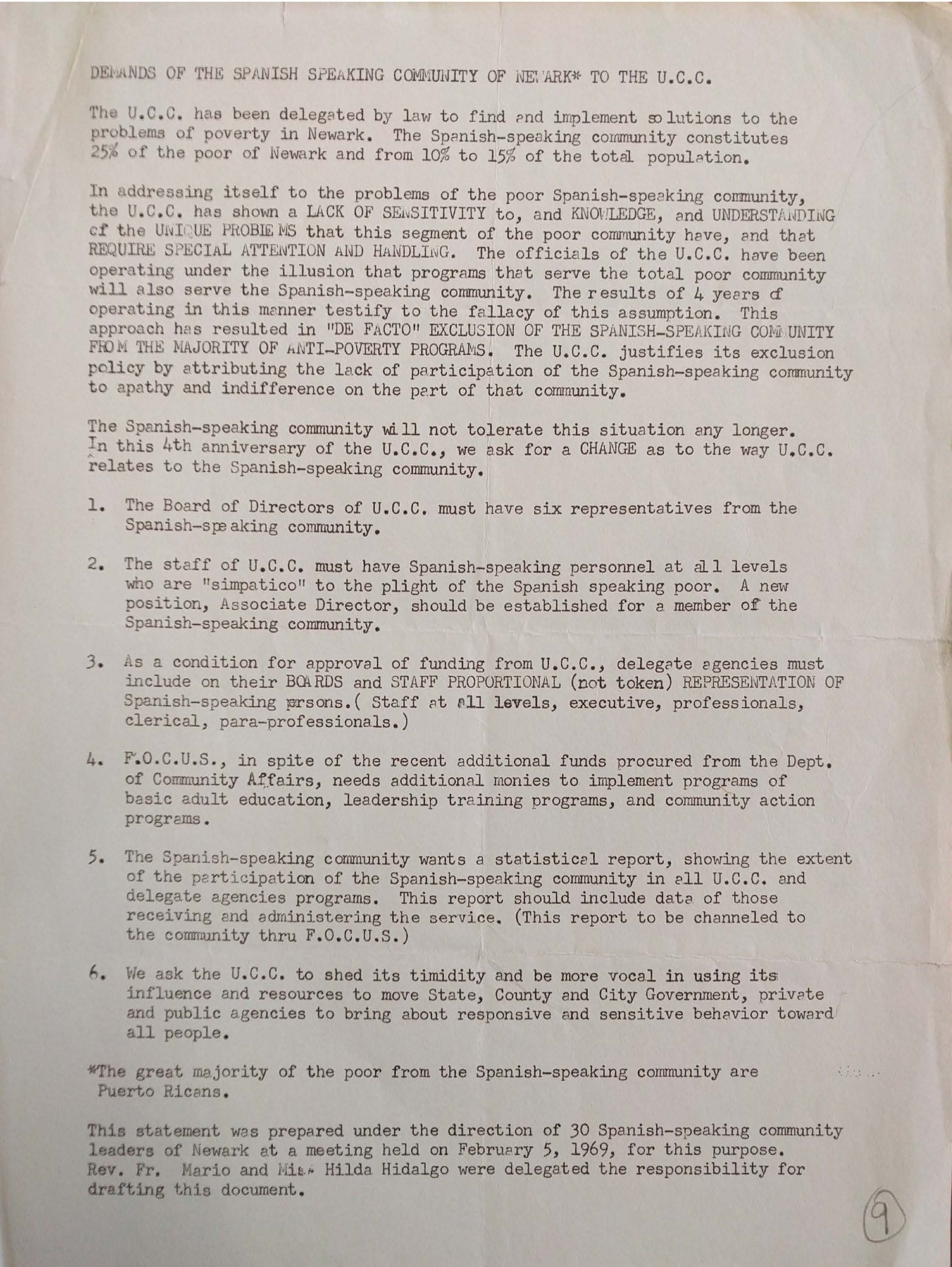

In 1965, the War on Poverty arrived in Newark in the form of the United Community Corporation (UCC), the city’s Community Action Agency. Hidalgo served as an assistant secretary and became an active voice and leader in the UCC, particularly regarding the needs of the city’s poor Puerto Rican and Spanish-speaking communities. To address these needs, Hidalgo helped form the Field Orientation Center for the Underprivileged Spanish-Speaking Residents of Newark, NJ (FOCUS- Newark). That same year, Hidalgo ran with George Richardson on his United Freedom Ticket campaign and took part in efforts by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and others to demand a civilian police review board after Lester Long was fatally shot by a Newark policeman in 1965.

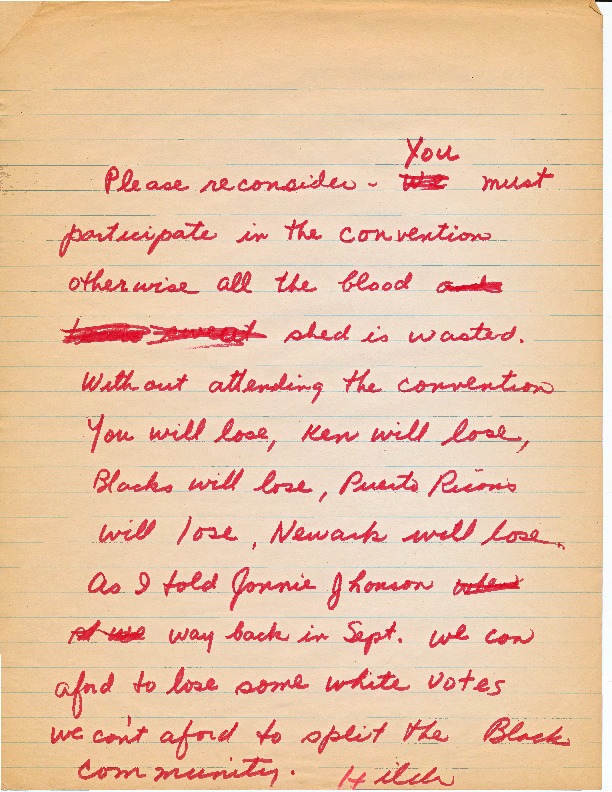

In 1969, Hidalgo served as secretary for the Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention, which was organized to nominate the “Community’s Choice” for candidates in Newark’s 1970 mayoral and city council elections. The Convention’s efforts led to the election of Newark’s first Black Mayor, Ken Gibson, and first Puerto Rican Deputy Mayor, Ramon Aneses.

In the 1980s, Hidalgo formed the Puerto Rican Congress and joined in coalition-building efforts with African American organizations to help get Latinx people elected to public office. During this time, Hidalgo was issued several death threats and once had her car torched.

During her years in Newark, Hidalgo co-founded and presided over Aspira of New Jersey, La Casa de Don Pedro and the Puerto Rican Congress. Additionally, Hidalgo was co-founder and Board member of the United Community Foundation. She was also on the board of the Newark Urban League and United Community Corporation. She chaired the first Puerto Rican Convention of NJ and served as Vice-President of the New Jersey Chapter of the National Association of Social Workers.

References:

Hilda Hidalgo explains the racial polarization of Newark in the 1960s and its impacts on the city’s Latinx communities. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Letter from Hilda Hidalgo urging participation in the 1969 Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Statement of demands issued to the UCC by 30 “Spanish-speaking” community leaders. The document was drafted by Rev. Fr. Mario and Hilda Hidalgo. — Credit: Newark Public Library