George Richardson

In 1960, George Richardson was a bartender and manager of Knobby’s bar in the Central Ward, and organizer of Knobby’s softball team. The group could not get a decent ball field and they only got promises from city hall. That’s when Richardson decided they had to become political, and so he put together a slate of district leaders, won several seats, and joined forces with Honey Ward, a local leader in Newark’s Central Ward..

Richardson and Ward demanded that Dennis Carey, Essex County Democratic Chairman put more blacks on the ticket for county and state offices at a meeting. (The County Chairman had the power to endorse a candidate, which put the candidate at or near the top of the ballot; and access to Party funds). A scuffle broke out at the meeting and Richardson took the microphone from Carey. The next day, Carey met with Ward and Richardson, and said he would support Ward for Central Ward Chairman and Richardson for a state Assembly seat in the 1961 election.

Ward won in 1960, and Richardson won in 1961. In 1962, Addonizio became mayor and appointed Richardson as Insurance Commissioner for the city of Newark.

However, in 1963 Richardson supported the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in petitioning Mayor Addonizio for a civilian police review board, because of the rampant cases of police abuse in Newark. Addonizio fired Richardson, and he lost his position on the line for re-election in 1963. Richardson then organized an insurgent political organization called the New Frontier Democrats, which ran people for several county and state seats. This split the Democratic Party, caused Richardson to lose friends (like Honey Ward); and the Republicans got control of the NJ State Assembly.

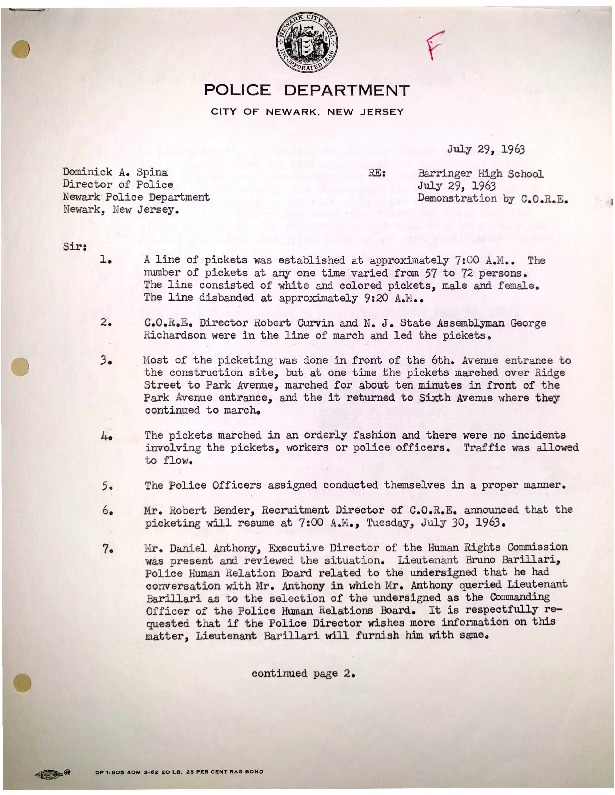

Richardson was instrumental in coordinating protests against hiring discrimination at the construction site of Barringer High School in 1963. During the Barringer protests, Richardson helped to form a coalition of civil rights, religious, and labor organizations known as the Newark Coordinating Council to demand racial equality in hiring in the building and construction trades. The Building and Industrial Coordinating Committee (BICC) was also an outgrowth of the Barringer struggle. These protests marked the emergence of large-scale, sustained civil rights activity in the city.

Richardson continued his advocacy against racism in alliance with groups such as CORE and the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal. He ran another slate of candidates in 1965 under the banner of the United Freedom Democratic Party, lost to Irvine Turner for the City Council seat in 1966, and to Ken Gibson for Mayor in 1970. Ironically, it was George Richardson who put Ken Gibson up to running for Mayor in 1966, when Gibson lost to Hugh Addonizio.

Richardson was one of the only African American politicians in Newark’s modern era to rely upon an independent party to seek election, in defiance of the Democratic Party.

References:

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power, unpublished chapter, “Allies and Adversaries”

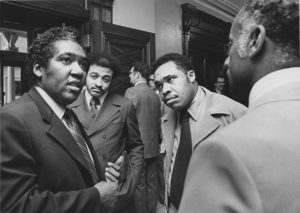

George Richardson describes how he got involved in the political scene in Newark’s Central Ward in the 1950s. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Newark Police memo on protests at the Barringer HS construction site in July, 1963, naming Richardson as a leader of the demonstration with Bob Curvin of CORE. — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

Community activist Derek Winans discusses George Richardson’s role in organizing the Newark Coordinating Council. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Clip from the documentary “Troublemakers,” covering NCUP’s involvement in George Richardson’s 1965 State Senate campaign. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection