Eulis “Honey” Ward

Eulis “Honey” Ward was born October 25, 1923 in Key West, Florida and moved to Newark with his family two years later. Ward grew up in the predominantly Black old Third Ward and graduated from South Side High School. While Ward was growing up in the 1930s-1940s, racism and segregation were a part of daily life in Newark, and Ward recalled seeing “White Only” signs on rooming houses on Belmont Avenue and segregated theatres on Springfield Avenue. As a young man in the 1940s, Ward got into boxing after watching the successes of Joe Louis in the ring, “cause to whip a white man at that time was something that we all got [to think] about,” Ward later said. Ward would go on to become an amateur welterweight champion boxer.

After serving in the Army in World War II, Ward joined the Merchant Marines at the suggestion Morris Parker, a fellow boxer in Newark. It was Parker who also got Ward into the political arena in Newark after leaving the Merchant Marines. Parker was a district leader for Third Ward Democratic Chairman Charlie Matthews, and brought Honey Ward into the fold by canvassing in his district. From this beginning, Ward climbed the ladder of the political power structure in the Third Ward (later Central Ward).

At the time of Irvine Turner’s election as the city’s first Black councilman in 1954, Ward was working as a butcher and member of the Meatpackers Union. He was a supporter of Turner in the election, and loyal to the Irish political bosses at the city and Essex County level.

In 1960, Honey Ward became the Central Ward Democratic Chairman, defeating the Italian Chairman, Salvatore Dispensere. Irvine Turner supported Dispensere and not Honey Ward. The Ward Chairman was elected based upon the number of elected district leaders he could bring to a meeting to vote him into office. District leaders run on the Democrat or Republican lines at county and state elections. So Honey Ward had to build his base by getting people elected, holding them in place until he accumulated enough votes to challenge, overcoming the promises for jobs and favors from the other side, and getting district leaders to stand up and vote against a white man; which is why Honey had to develop the muscle to protect himself and his supporters from physical violence. When he heard that a polling station at the 13th Avenue School was locked to prevent Blacks from voting, Ward kicked down the door of the school.

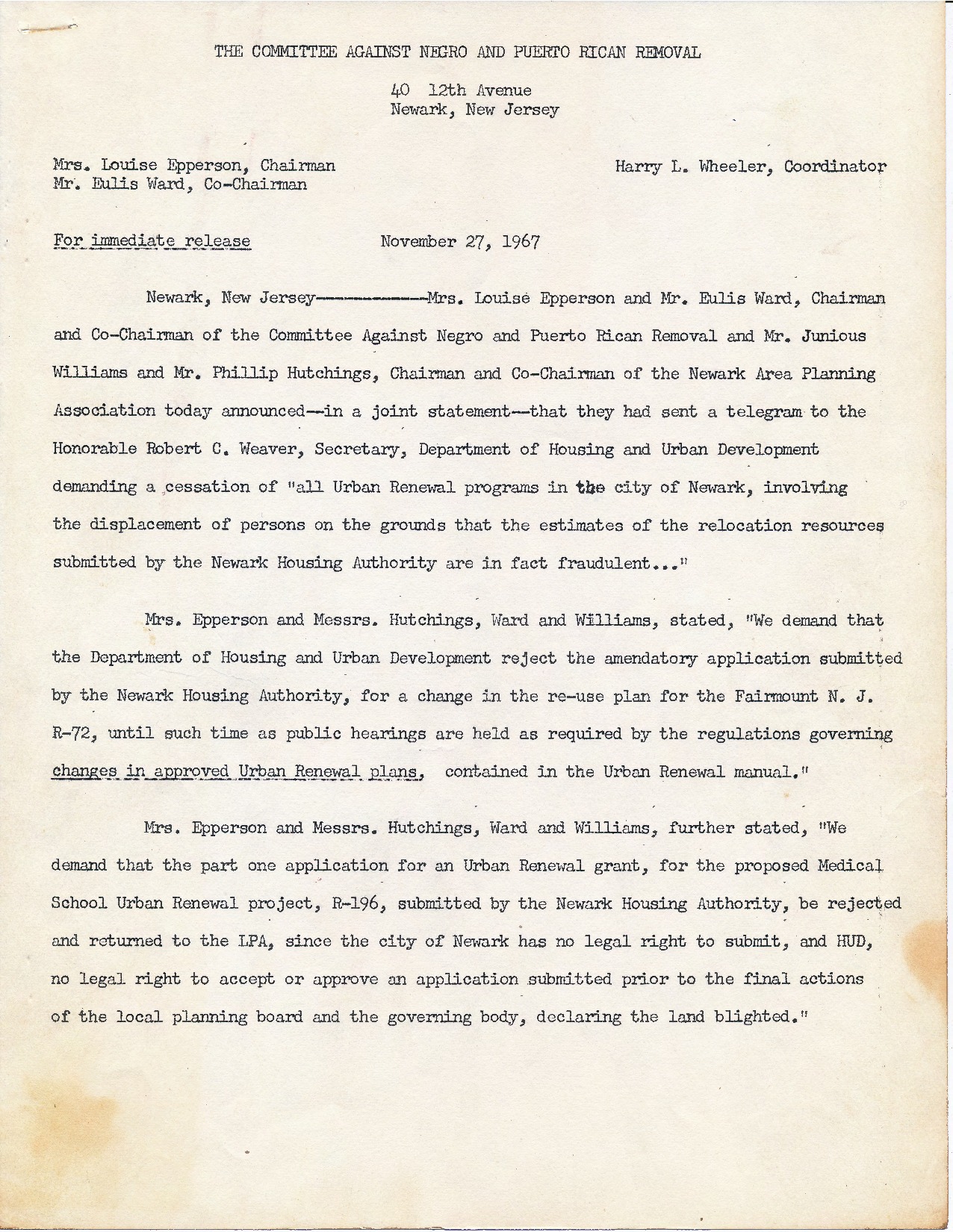

As the Civil Rights Movement emerged in Newark, Ward’s brought his brand of local politics into struggles for Black empowerment in the city. As a co-chairman of the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal, Ward took part in the struggle to prevent the construction of a state medical school on 180 acres of land in the Central Ward. For Ward, the urban renewal project was a personal affront to the efforts that he and many others had taken in the Central Ward to build a political base. “We had broke our ass registering Blacks…and they’re all being displaced, which cut our votes down enormously,” Ward later recalled. Ward also joined the Black political organization, the United Brothers, to run candidates for the 1968 City Council election and 1970 Mayoral election.

References:

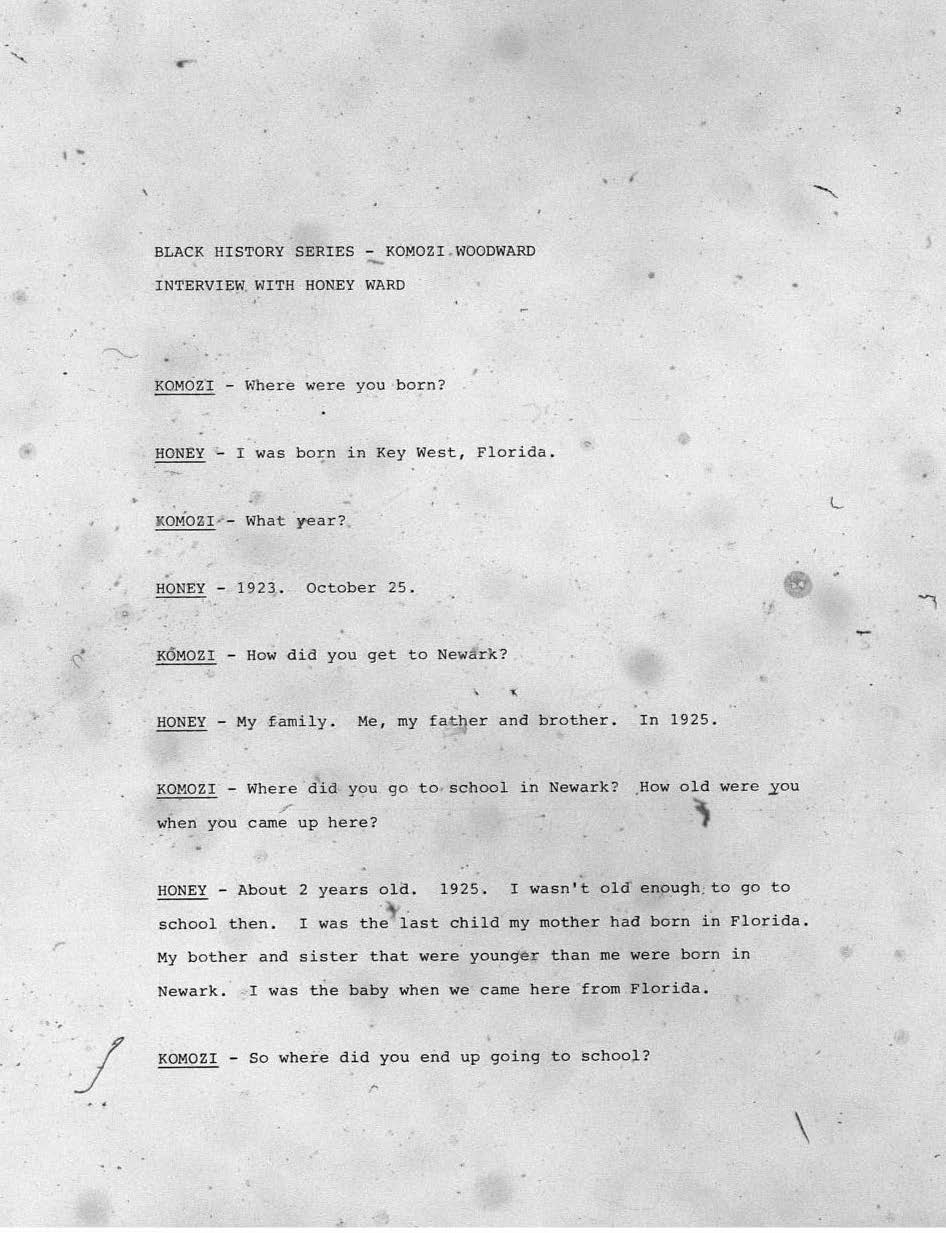

Komozi Woodard Interview with Honey Ward, 1986.

Junius Williams Interview with Eulis “Honey” Ward.

Transcript of an oral history interview with Eulis “Honey” Ward, conducted by Komozi in 1986. –Credit: Komozi Woodard

Letter from the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal to Robert C. Weaver demanding that all urban renewal projects in Newark be stopped. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection