Donald Tucker

Donald Tucker was born in Newark in 1938 and raised in the Down Neck (Ironbound) section of the city. After dropping out of East Side High School to join the Air Force, Tucker eventually graduated from Central Evening High School and later from Garnett College in Montclair, VT. Although Down Neck was a predominantly Black neighborhood at the time, Tucker remembered his first experience with racism when some white folks came by and spit at him when he was about seven years old. In spite of the racism Tucker and his family experienced in the city, “race pride” was a prevalent topic in conversations in their household. Tucker later recalled when he was about eight years old learning from his parents about the legacies of Black Southerners, and being taught that “you may be poor but you don’t have to be dirty. You may be poor but you don’t have to be dumb.”

Tucker first became involved in the Civil Rights Movement through the NAACP Youth Council in 1956 while stationed with the Air Force in Riverside, CA. Upon returning to Newark in 1960, Tucker found that the city’s NAACP branch was “not working fast enough,” so he joined the newly formed Newark-Essex chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). “We used to involve ourselves in confrontations, demonstrations all over Essex County,” Tucker said of his experiences in CORE, “whether it was in housing, employment, basic discrimination.”

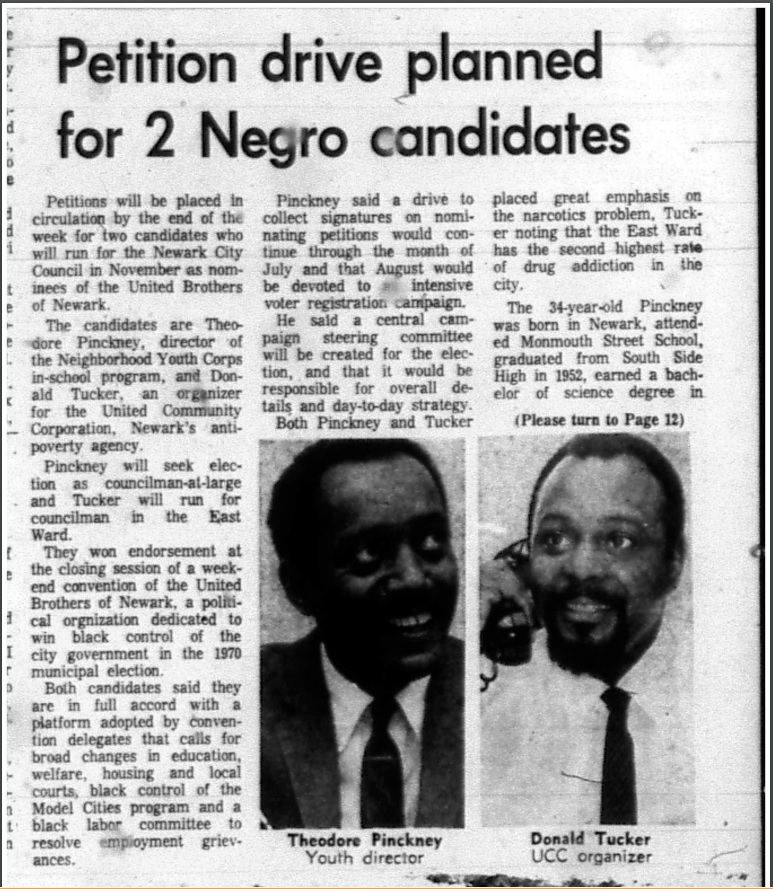

When the War on Poverty came to Newark in 1965 through the city’s antipoverty agency, the United Community Corporation (UCC), Tucker took an active role as an organizer with Area Board #5, “Operation Ironbound.” Because of his work in the East Ward, Tucker joined the efforts of the United Brothers and Committee For Unified Newark (CFUN) to create a Black united front in the city. In 1968, the United Brothers nominated Tucker and Ted Pinckney as candidates for that year’s City Council elections to fill vacancies, and again in 1970. Although both lost in both elections, the United Brothers and CFUN played a significant role in electing Ken Gibson as Newark’s first Black mayor two years later in 1970.

Tucker went to work for Junius Williams in the Model Cities Program, upon the election of Ken Gibson. Tucker was finally elected to the City Council in 1974 and went on to serve on the council for 31 years. He was the founder and president of the New Jersey Black Issues Convention, which first convened in 1983. From 1980-1984, Tucker was president of the National Black Caucus of Local Elected Officials and later represented Newark in the NJ State Assembly from 1998 until his death in 2005. In addition to his political involvement in Newark, Tucker also helped to organize the Essex Council on Drug Addiction, created a non-profit, cooperative Day Care Center, established the city’s first free high school equivalency tutorial program, and helped get Seton Hall University to establish a degree-granting Black Studies Center.

When about his motivations for engaging in struggles for civil rights in Newark by Komozi Woodard in 1986, Tucker said “…because we were very much concerned with change. We were tired of dealing with the subjugation of Black people. We were tired of dealing with the stereotypical attitudes…and we wanted to be self-determining.”

References:

Komozi Woodard Interview with Donald Tucker, January 31, 1986.

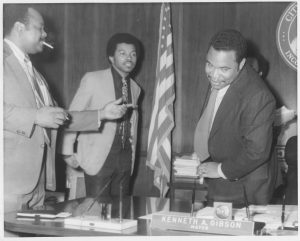

Community organizers at a press conference during the 1967 Newark rebellion. Left to right: Jesse Allen, James Hooper, Donald Tucker, Marion Kidd, and Phil Hutchings. (Newark Public Library)– Credit: Newark Public Library

Article from the Star-Ledger on June 25, 1968 covering the nomination of Theodore Pinckney and Donald Tucker for City Council positions during a political convention held by the United Brothers. — Credit: The Star-Ledger

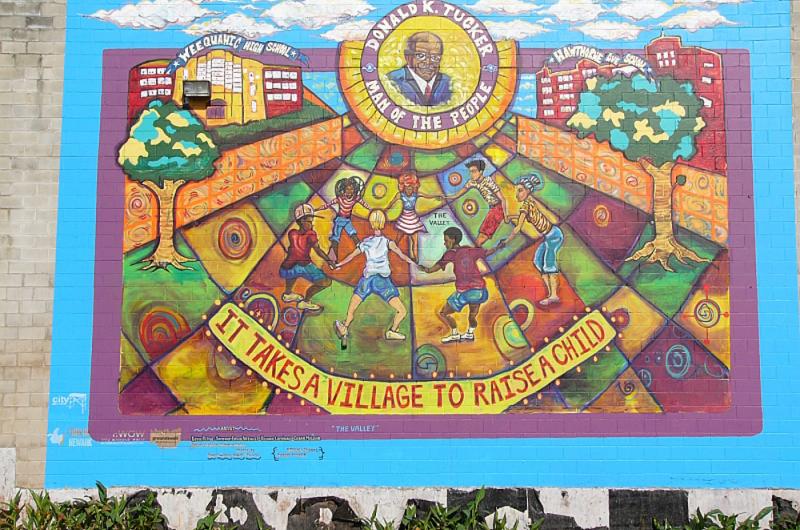

Mural at 43 Elizabeth Avenue memorializing Donald Tucker, created through a partnership of Groundswell, City Without Walls, The City of Newark, The Centre, and the Donald Tucker Center in 2010. — Credit: Groundswell